The Plague

By Brian Eggert |

Charlie Polinger makes a confident directorial debut with The Plague, an uneasy psychological thriller centered on a group of mostly 12-year-old boys at the Tom Lerner Water Polo Camp. Set in 2003, this nerve-racking coming-of-age tale follows Ben (Everett Blunck), who recently moved to the area and yearns for approval and inclusion. But there’s no more unforgiving set of social codes than those laid out in middle school, a time when preteen boys will tease anyone even slightly dissimilar and ultimately turn them into a pariah. Ben must contend with a group of merciless boys, headed by the cruel Jake (Kayo Martin), who maintain a cooties-style taunt called “The Plague.” Eli (Kenny Rasmussen), an outsider at the camp, has acne and a skin rash, which the other boys claim is a mysterious, contagious disease. They react to Eli by making a spectacle out of avoiding him and, after any physical contact, vigorously washing the imaginary disease away. But is the Plague a mocking fiction or does Eli have something genuine? Ben isn’t sure.

The Plague would make a fine double-feature with Lord of the Flies—preferably Peter Brook’s 1963 version—given its examination of the social mores that shape preadolescent behaviors, which reverberate into adulthood. A mixture of peer pressure, bullying, and groupthink stands as the foundation of this strict social stratum. Ben wants to be included, yet he doesn’t think Eli is all that bad. He’s a little weird perhaps, with a penchant for random references, macabre practical jokes, and dancing with unselfconscious freedom. Under different circumstances, Ben and Eli might have been friends. But associating with Eli is social suicide for Ben—and he’s already the butt of one joke. Jake gives Ben the nickname “Soppy” after he fails to articulate the “t” when saying “stop.” Ben tries to play it cool, like it doesn’t bother him, but it does. He just wants to be accepted. The dynamic begins to feel like the first half of Full Metal Jacket (1987), with Eli and eventually Ben as the resident Pvt. Pyle. There’s even a scene similar to the late-night soap beating, albeit with cockroaches.

Polinger’s technical execution is controlled and thoughtful right from the opening shot—an underwater image from within a calm indoor pool. One after another, the boys break the surface in slow-motion, swimming and treading water like gangly aquatic creatures who disturb the peace. The muffled sound of splashing is accompanied by Johan Lenox’s discordant, amelodic score, full of ambient sounds, paranoid strings, and echoing thumps. The music builds the tension between our certainty that there is no “Plague,” that it’s merely a cruel game played by boys at their most ruthless age, and the visual evidence to the contrary. Perhaps it’s a psychosomatic response when Ben develops a rash on his back like Eli’s. Maybe it’s just acne that develops on his face, brought about by puberty. I remember developing hair on my legs in the fourth grade and the other boys poking fun at me about it, calling me Beast from X-Men. Boys will mock any disparity, even if in a few months or years, they’ll get hair on their legs too. As for Ben, he’s almost certain there’s nothing really wrong. Almost.

On the periphery of these cruel games is their coach, Daddy Wags, played by Joel Edgerton in a small but substantial role. Edgerton’s presence is sturdy and fatherly, bringing sober guidance to Ben. The coach doesn’t tolerate bullying either, as evidenced by Jake eventually getting booted from the camp. The child actors also shine, never once giving off the stagey quality some kids never shed in youth performances. Rasmussen, playing a tragic oddball, recalls not only Vincent D’Onofrio in the aforementioned Stanley Kubrick film but also Nicholas Hoult’s debut role in About a Boy (2002), with equal parts strangeness and sympathy. Most effective is Blunck, who exudes uncertainty and vulnerability in this coming-of-age tale. He appears to hesitate with every line, as though the next word could make him the boys’ next target, so he’d better pick the right one.

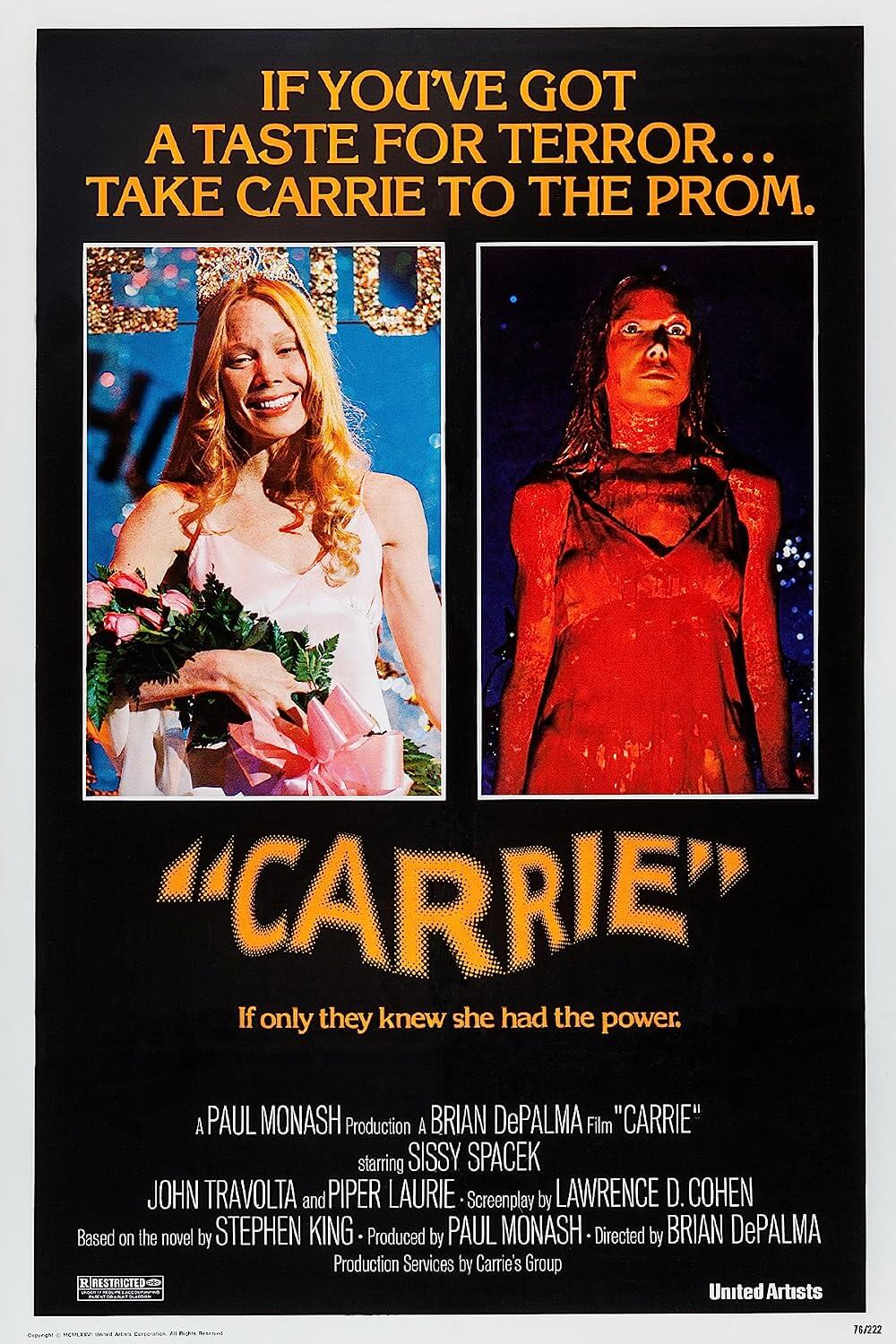

Assembled with precise, intentional filmmaking, seen in cinematographer Steven Breckon’s textured 35mm compositions and the editors’ (Henry Hayes and Simon Njoo) sharp cutting, The Plague plays with ideas of body horror while reducing them to a grounded, yet no less nightmarish reality. Unlike the punishing harassment in Full Metal Jacket or even Carrie (1976)—another film obviously on Polinger’s mind while making this film, complete with traumatic shower and locker room scenes—there’s no need for a mysterious disease, extreme violence, or supernatural forces for the director to make his point. It’s a nerve-racking experience because we’ve all faced the kind of social pressures and torment on display here. However, Polinger acknowledges that these conditions, while a phase, continue beyond school.

A final dance sequence, where Ben finally sheds his need to fit in and adopts some of Eli’s moves, recalls the one at the end of Claire Denis’ Beau Travail (1999). In that film, the rigid conformity of an all-male French Foreign Legion section has dire consequences, and only after years of reflection can Denis Lavant’s character free himself from the unyielding physical discipline to dance in one of the most frenetic dances ever caught on celluloid. Denis’ film uses Corona’s “The Rhythm of the Night,” while Polinger’s film ends with a song from the same era of the early 1990s—Moby’s “Feeling So Real.” Blunck’s dance is less skilled than Lavant’s, but it’s no less inspired, freeing, and cathartic. Even though there’s a thick soup of antecedents to The Plague that prevents it from being called wholly original, it’s nonetheless a compelling debut for Polinger and a promising start to a directorial career.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review