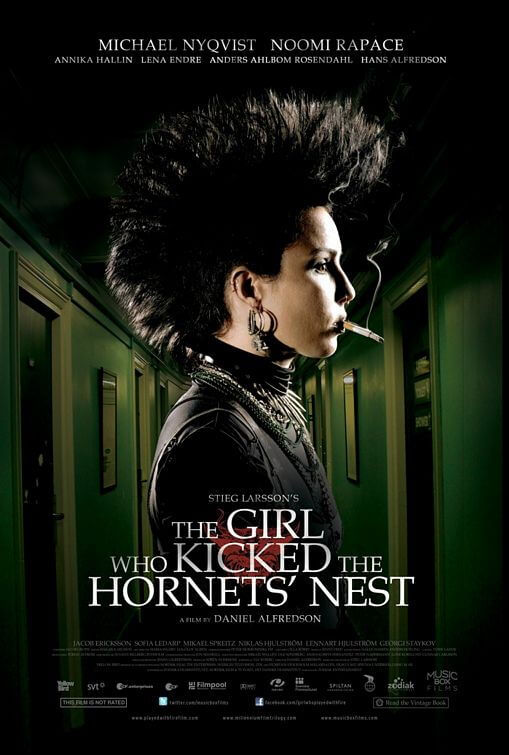

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest

By Brian Eggert |

The final chapter in Steig Larsson’s “Millennium Trilogy”, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, works better than its immediate predecessor by vindicating the protagonist, a resourceful computer hacker, and investigator with almost as much black makeup and piercings as she has emotional baggage. Lisbeth Salander, played with cold intensity and guarded emotions by Noomi Rapace, may be the only reason to watch these films. And therein resides the problem with this last film, since the story limits the character in more ways than one, keeping her from doing what she does best: trying to compensate for the narrative clichés, structural inconsistencies, and missteps in tone running rampant through Larsson’s material.

To understand anything in this third film, casual viewers are obligated to watch The Girl Who Played with Fire, which sets up every narrative cord carried over here. As a result, the concluding episode fails as a standalone film, unlike the first film, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. To avoid forgetting any important details, viewers are encouraged to watch the latter two films back-to-back. Much of the two-and-a-half hour runtime of this entry involves exposition: it connects the dots made in the previous two films and exposes details of the conspiracy, but with very little character development to speak of. Being familiar with these characters beforehand is a necessity, as the filmmakers rush to include as many details as possible from Larsson’s novel.

Structurally, this sequel avoids the most dynamic element of Larsson’s trilogy: the relationship between Lisbeth and her suitor from Millennium magazine, investigative reporter extraordinaire Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist). When the film opens, we find Lisbeth recovering from nearly fatal head injuries incurred by her grotesque Russian spy father and her blond thug half-brother. She remains isolated for most of the film in a hospital room or prison cell, looking out from the inside as undisclosed parties attempt to secure her fate. Separated throughout the picture, Lisbeth and Blomkvist share only one or two scenes together, and those are momentary, with few lines of dialogue exchanged between them. Otherwise, all of their communication is handled via emails and go-betweens, which keeps the audience distanced from the surging romantic tension between the two.

In attempting a larger-scale story to close out the trilogy, the film fails to build much tension. Conspirators make threats to Blomkvist and his staff. There’s a half-hearted attempt on Blomkvist’s life. Lisbeth’s gigantic half-brother watches from afar, waiting to strike. And investigations of investigations lead up to Lisbeth’s trial for murder, the centerpiece of the story. In tidying up the events from the previous two films, screenwriters Jonas Frykberg and Ulf Ryberg forget a few details. From The Girl Who Played with Fire, the murders of a freelance writer and his girlfriend for which Lisbeth was framed are never mentioned in court, which would seem to be a crucial detail. Nor do we see her exonerated for the murder of the rapist lawyer, although the footage of her rape plays a vital role. That such plot details are simply skipped over renders the middle film (and also the weakest) in the trilogy almost pointless, yet it must be endured for anything in the finale to be understood. But by the time the bad guys receive their comeuppance in open court, resulting in the protagonist’s acquittal, missing details hardly matter, sloppy storytelling or not.

Daniel Alfredson returns as director, though luckily no chase or fight scenes threaten to expose his lack of ingenuity behind the camera. Viewers who questioned the sexual paradoxes in the first two films—the bouncing back-and-forth between fetishized rape and sex scenes—will be relieved, as Alfredson omits any bedroom antics, forced or voluntary. This choice allows the audience to focus less on the sometimes questionable perspective choices made by the filmmakers and more on the unfolding drama. It should also allow us to observe the nuances of Rapace’s performance, except that her character sits on the sidelines for most of the film.

To compress the story into pure exposition, the film uses a courtroom trial: it reduces a multifaceted narrative and deconstructs any dramatic subtlety by condensing a character’s complex and painful life down to a simple verdict. Manipulative though a trial may be as a storytelling device, it gets the job done. However, for all its dramatic straightforwardness, the trial limits Lisbeth to a passive protagonist. She remains mostly silent through pretrial interviews and virtually monosyllabic in courtroom testimony, whereas in the previous two films, she demonstrated an aggressive involvement in her fate. Only in the final scenes, when her half-brother shows up to settle his score, does Lisbeth break from her more than two-hour hibernation.

The final scene brings the trilogy to an abrupt and unsatisfying conclusion, ending with a moment of romantic unease that may never be resolved, as Larsson killed himself before finishing his fourth novel (in a proposed seven-part saga). Thus, the arcing narrative throughout the three stories feels open-ended, frustratingly so. Granted, the closing has a certain emotional truth that reflects upon Lisbeth’s cautious nature, but after such a crowd-pleasing court case, the story has already opted into too much dramatic pandering to stop there. The filmmakers no doubt felt a responsibility to remain faithful to Larsson’s books, but their devotion to the material overlooks otherwise apparent weaknesses in The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, a moderately satisfying conclusion to an overrated trilogy.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review