Reader's Choice

The Front Room

By Brian Eggert |

There’s no arguing with zealotry. No rationalizing with fanaticism. No debating superstitions. The Front Room is about how, in America, some Christian extremists think they know what’s best for everyone else, and telling them “No thanks” doesn’t work. The story involves one such fundamentalist who moves in with her stepson and his pregnant wife. Steeped in the “signs and wonders” of the Holy Spirit, she embeds herself in the family like a parasite, feeding on their energy and attempting to replace it with her own. A proud member of the “United Daughters of the Confederacy” who makes no apologies for her heritage in Southern racism, Solange is played by Kathryn Hunter in a vivid performance. Her body appears withered and frail, but she stomps with a cane in each hand as she walks, her movements resembling a contorted spider. Her gruff voice is loud and commanding, and she speaks with an authority that others yield to and admire. But for the non-believers who welcome Solange into their home, she’s a corruptive and hostile evangelical presence in their otherwise secular domestic sanctuary.

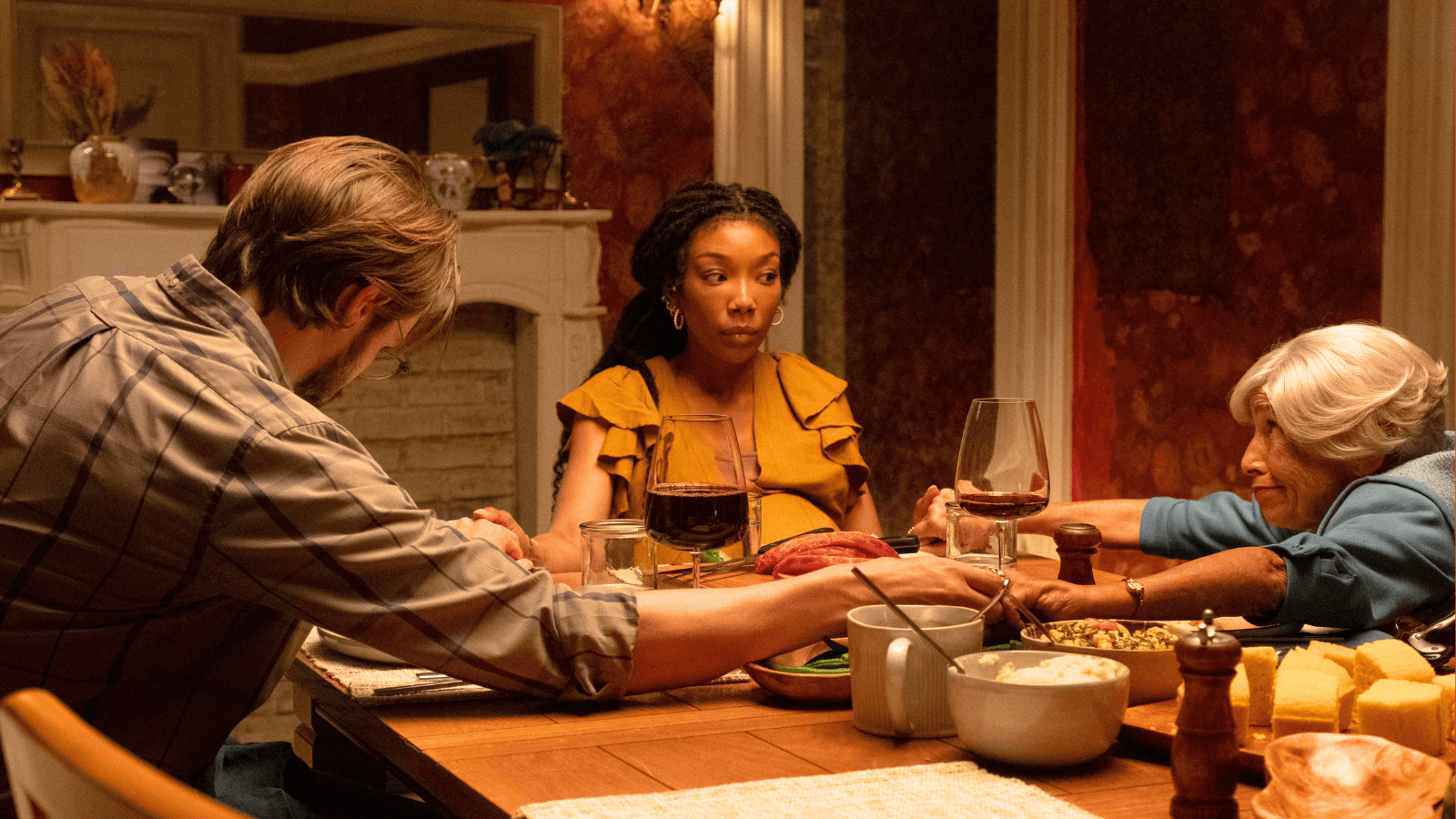

Brandy Norwood plays Belinda, an anthropology professor at a local college who finds herself unemployed as she prepares to go on maternity leave for her new child with Norman (Andrew Burnap), her husband, an underpaid public defender. Just as their financial woes mount, Norman’s estranged father dies, leaving his widow, Solange, to strike a bargain with the couple. She’s willing to hand over the entirety of her late husband’s considerable estate if they allow the infirmed, pious woman to live with them. Norman protests, still reeling from Solange’s cruelty to him as a boy. “We should focus on us,” he insists. But Belinda convinces him that the situation could solve their budgetary problems. When she first arrives at their home, Solange claims the ground-level room, originally intended as their child’s nursery. Her invasiveness continues when she inserts her Christian influence on the family, hanging paintings, crucifixes, and other imagery about the house. Belinda and Norman can hardly argue; after all, Solange has rescued them with her money. But her presence soon becomes malevolent.

Distributed by A24, The Front Room marks the directorial debut of Max and Sam Eggers, half-brothers of Robert Eggers, director of The Witch (2016) and The Lighthouse (2019). Adapting the short story by gothic horror novelist Susan Hill, the siblings deploy an aesthetic that will look and sound familiar to fans of A24-brand horror (think Hereditary, 2018). The crisp lensing by cinematographer Ava Berkofsky is almost secondary to the heightened sound design by Ric Schnupp, who amplifies everyday effects—such as the thumping of Solange’s canes—to monstrous, deafening heights. Marcelo Zarvos’ music score is likewise affected, relying on a blend of jarring strings with an undercurrent of winding theremin notes, making the proceedings sound like an Atomic Age science fiction yarn at times. The aural treatment, which includes Hunter’s imposing voice, builds Solange into an uncanny presence that, despite her enfeebled body, establishes her as a sinister influence. Her presence in a couple of Belinda’s dreams twists Madonna and lamb imagery into surreal and nightmarish sights.

What begins as a series of minor encroachments on Belinda and Norman’s home soon escalates into Solange’s active attempt to become “mother” of the house. While slyly manipulating every interaction to her advantage, she uses her financial contributions to play the role of martyr-mother. She replaces the house’s furniture, complains about Belinda’s cooking, and regularly soils herself, requiring Belinda to clean her. There’s hardly any blood or violence in The Front Room, but Solange’s failing body is terrifyingly grotesque, from her gag-inducing pea-soup-colored mucus to the excrement she leaves in bed. It might be sad instead of vile, except Solange seems to delight in making Belinda clean up her so-called accidents (each announced by Solange screaming, “M-E-Double-S!”). It’s all the more troubling given the stepmother’s uninhibited racism and delight in tormenting her daughter-in-law with childlike outbursts. Moreover, Solange’s tendency to speak in tongues and commune with spirits has earned her some followers in the local religious community. It’s almost to the point where Belinda questions whether Solange has genuine supernatural abilities or has just manipulated coincidences for her purpose.

Along the way, The Front Room serves up an apt metaphor for how, for the last two thousand years, Christianity has co-opted iconography, significant dates, and mythologies established in earlier Greek, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian cultures and converted them. Belinda teaches a course on fertility goddess symbols and demonstrates how Christianity has taken and repurposed imagery, such as the Jesus fish, that started as non-Christian. At first, Belinda resolves to respect Solange’s views and pity her physical state. But after Solange’s repetitive attempts to seize control of the house and make Belinda look like an inadequate mother, Belinda begins to challenge her. A battle of wills ensues, first over Solange inserting Christianity into the home, then over her influence on the baby. The situation echoes how Christian groups have historically moved in and replaced the local belief systems, though Belinda proudly refuses to step aside. All the while, the film captures how some non-believers see radical Christians as cultish radicals, especially in scenes of blathering, unintelligible glossolalia that have profound meaning to them but sound unhinged and scary to others.

If the setup concerning an unwanted house guest seems simple, The Front Room explores race, religion, and domestic conflicts across generations, capturing how different ideologies can register as intrusive, if not altogether unsettling. It’s also another in a long line of 2024 films that exploit timely dread about pregnancy in a Christo-fascist America, which reflects the post-Roe anxiety about the diminishing power women have over their bodies. There’s not much to the movie beyond this centralized struggle over the home, but the performances boost the material. Norwood, no stranger to horror after her role in 1998’s I Still Know What You Did Last Summer, is effective in her scenes of resigned acceptance, but she blooms when Belinda goes from frustrated and powerless to taking back her home. Even so, the Eggers siblings wouldn’t have much of a movie without Hunter, playing a character whose base behavior and unbending worldview have predatory overtones. Hunter’s performance is so convincing that just the sight of Solange becomes downright repulsive and hateful, making her one of the most compelling villains in recent memory. For that reason, and it’s not the only one, it’s worth seeking out The Front Room.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on October 24, 2024.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review