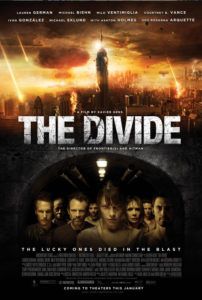

The Divide

2 Stars- Director

- Xavier Gens

- Cast

- Lauren German, Michael Biehn, Milo Ventimiglia, Ashton Holmes

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 112 min.

- Release Date

- 01/13/2012

The Divide opens with a shocker. Reflected in the eyes of Eva (Lauren German), we see a nuclear explosion detonate in New York City. Buildings topple. Fire fills the streets. All at once, screams and rushed cutting occupy the screen as people hurry down the stairs of their apartment building, hoping to escape before the structure collapses around them. Eva’s fiancé, Sam (Iván González), quickly grabs her and leads them toward the secure basement along with a small crowd of others. Once inside, behind a locked metal door, they’re seemingly safe from whatever unexplained terror has occurred topside. But now they’re trapped along with eight other frightened, traumatized, and degenerating survivors with limited food and no hope of rescue. If there’s anything we’ve learned from stories like Lord of the Flies, it’s that when people are cut off from civilization, things go bad—real bad—all too quickly.

Power struggles abound as the group contends with the building’s super, Mickey (Michael Biehn), a cigar-chomping, Arab-hating, walking-taking cliché, formerly of the NYFD, who lost his family in 9/11. His obvious backstory is offset by lesser-developed characters that get by on the talent of Hitman director Xavier Gens’ ensemble cast. The building’s security guard Devlin (Courtney B. Vance), for example, has no backstory, but his character is believable because Vance plays him with some nuance and compassion. Fuelled by his (apparently not unjustified) survivalist paranoia, the exaggerated Mickey has built the basement into a kind of bomb shelter and rules with an unfair and dogmatic hand. Biehn plays him a few notches crazier than a similar role he had in James Cameron’s The Abyss.

As he jealously rations food and water, Mickey’s unreasonable commands represent an I-don’t-need-to-explain-myself sort of governmental figure the film aligns with George W. Bush. The group eventually rebels and ties Mickey down to a chair, and then the control takes a twisted turn as gradually two punks, Josh and Bobby (Milo Ventimiglia and Michael Eklund), assume command. Their brand of management becomes even more debased, beginning like a post-traumatic stress-induced nightmare and veering off into torturous, morbid territory. Eva and Sam, meanwhile, sit back and observe as their situation worsens over the coming days, weeks, et cetera. Exactly how long things take to decline remains unclear. Sickness sets in. Josh and Bobby’s hair falls out, their bodies decay, and their minds bend from what we assume is radiation poisoning. Their power-hungry perversions transform grieving mother Marilyn (Rosanna Arquette) into a numb-the-pain-with-sex slave. Matters digress into increasingly disturbing sadomasochistic atrocities, none of which resemble anything like believable human behavior.

Herein lies the trouble with Karl Mueller and Eron Sheean’s script. When all humanity fades from the scene, the story devolves not into a sophisticated metaphor about how quickly civilization breaks down or an allegory about awakening from apathy when faced with atrocity but into an exhibition that chooses to test its limits of debasement within this material. A comparable film like Apocalypse Now treats the disintegration of humanity with an awe-filled distance, allowing the audience to use our imagination through poetic cuts and brief glimpses into the limits of human terror in Kurtz’s camp. Gens exploits the situation for shock value with oddities and gore, and any hope for a lesson is lost underneath our disgust. Nevertheless, the film does an ample job of keeping us involved. Initially, we want the group to take Mickey down, but in time letting him loose seems to be their only hope against the now-bonkers Josh and Bobby.

The film’s in-your-face symbolism becomes even more confusing thanks to numerous underexplored plot points. Early in the film, we learn Eva is pregnant with Sam’s child. Nothing happens with this information; it’s mentioned once and then never comes up again. She expresses no concern for her unborn child and displays no physical symptoms of her pregnancy. Later, their shelter receives a visit from armed men in biohazard suits. Are they the enemy? Are they American? What do they want with Marilyn’s daughter, whom they kidnap for experimentation? These details remain head-scratching not only because they go unexplained but more because they were brought up at all. Similar films like The Mist and Right at Your Door at least offer vague explanations to get the viewer beyond situational questions. Here, one endures two hours of hell without knowing why.

Of course, knowing what happened is less important than the film exposing the evil that lurks inside some people, just waiting to emerge given the right set of circumstances. The Divide suggests that some will retain their humanity in such post-apocalyptic situations, while others will simply snap. It’s a familiar notion, explored more thoroughly elsewhere, and presented here in an incredibly ugly film. Gens lends a certain gloss to the production, managing his effective ensemble in a close-quarters environment with some slick camerawork (and some very derivative of David Fincher) and a clear use of space. Yet, instead of exploring these themes with insight, the film’s muddled metaphors suggest the filmmakers have resolved to explore the situation merely to test the limits of revulsion, leaving the audience with an expected sense of doom, but not in a way that fills us with admiration for the film that evoked it.

The Road

The Road  Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes  Cloud Atlas

Cloud Atlas