She Said

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on November 2, 2022, for the 2022 Twin Cities Film Fest.

In early October 2017, Megan Twohey and Jodi Kantor published their exposé, “Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades,” in the New York Times. Their story detailed how Weinstein, bolstered by the Miramax co-founder’s fearmongering, payoffs, and systemic protections at the studio, quieted allegations of harassment and sexual assault going back decades. Ultimately, the story led to 82 women coming forward about Weinstein and his subsequent imprisonment, while also lighting the fuse on the #MeToo movement. The impact on power dynamics and discussions of workplace abuse the world over is immeasurable. She Said dramatizes Twohey and Kantor’s reporting, with Carey Mulligan and Zoe Kazan in their roles, respectively, interviewing victims who are afraid or legally bound not to speak. Most people watching the film, produced by Anapurna and Plan B, will be familiar with the outcome, given the widespread sociopolitical reckoning that it would prompt. But even knowing the story’s outcome, the direction by Maria Schrader and engrossing performances throughout make the film powerfully told and wholly engaging.

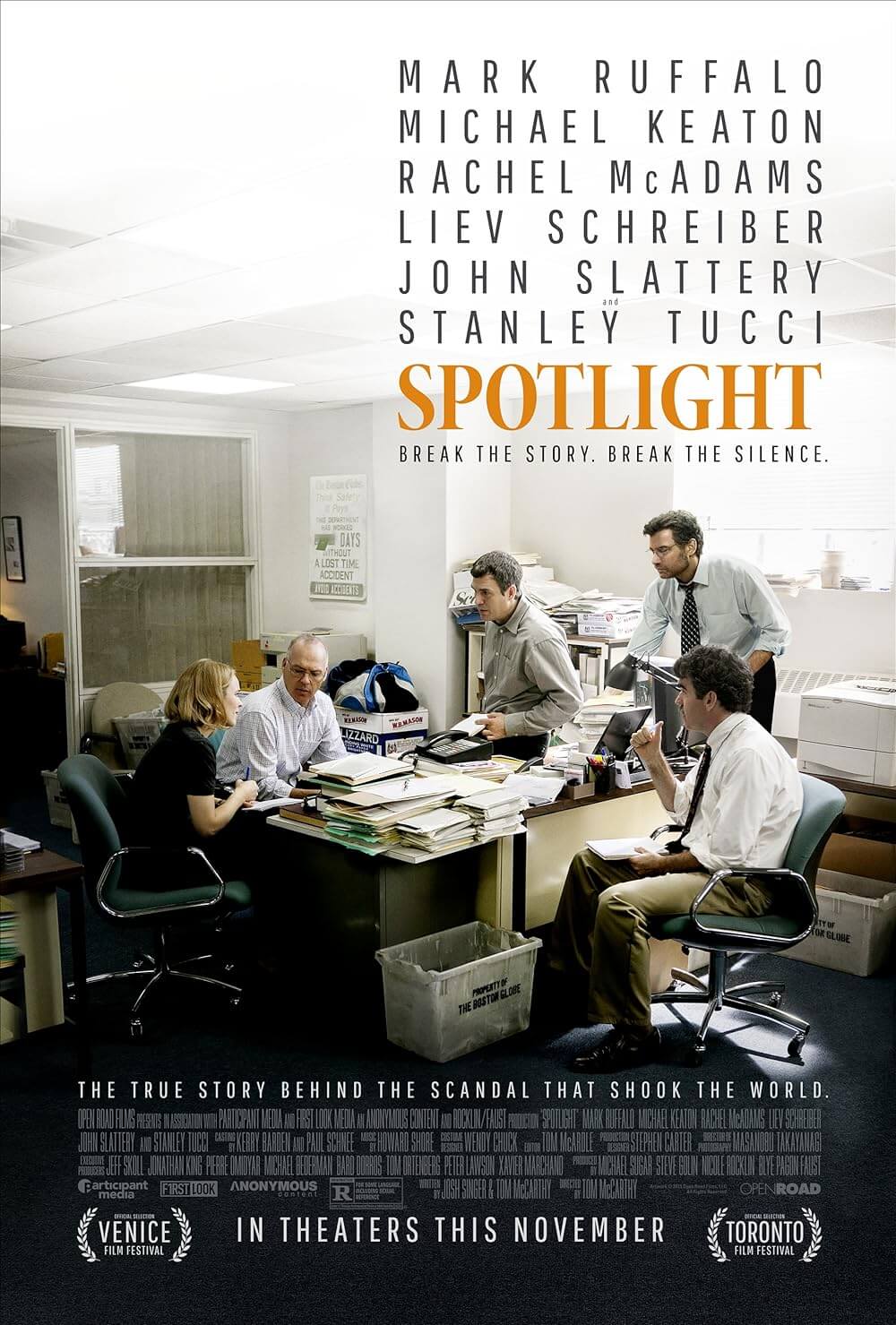

She Said hews closely to its journalistic antecedents, namely All the President’s Men (1976) and Spotlight (2015), where the character development is somewhat thin compared to the momentum of the procedural. The main character is the investigation, whereas, say, The Assistant (2020), the more subtle drama about Weinstein’s behavior, entrenched the viewer in one character’s subjectivity. But since familiar actors occupy most of the cast, there’s a greater sense of each character because of the performer’s established screen presence. The reporters knock on doors, interview witnesses in restaurants, and spend too much time away from their families—but not so much that it strains their marriages or leads to clichéd melodramatic scenes about discord at home. Fluid shots through bustling offices show the newsroom teeming with activity. Our heroes conduct research and write their article late at night, illuminated only by their laptop screens. When they eventually file the copy, one of the film’s most compelling scenes shows the reporters, editors, and copy editors gathered around a computer monitor, reading the text in silence one more time before finally pressing the “Publish” button. It’s wildly suspenseful for what amounts to a modest moment.

The screenplay, credited to Rebecca Lenkiewicz (Disobedience, 2017) and based on the 2019 book by Twohey and Kantor, opens with Twohey working on a story about sexual assault allegations against Donald Trump only to see her work overlooked and her subject become POTUS. Meanwhile, newish reporter Kantor, whose background involves Amazon labor disputes, begins to investigate claims against Weinstein but finds her sources, including Rose McGowan (whose voice is uncannily replicated offscreen by Kelly McQuail) and Ashley Judd (as herself), unwilling to be a named source and unconvinced that the story will amount to repercussions. Kantor asks whether McGowan went to the police about her encounter with Weinstein, and her response—“Can you see the police taking my side?”—is symptomatic of the widespread anxiety and doubt victims of abuse have about coming forward. When Twohey returns to work after giving birth to her first child and grapples with postpartum depression, she dives back into reporting. Her editor, Rebecca Corbett (Patricia Clarkson), teams Twohey and Kantor on the Weinstein story, compelling her reporters to “investigate the whole system.”

But as Kantor has already discovered, many of those who have had experiences with Weinstein refuse to go on the record, either out of fear, no desire to relive their trauma, or because Weinstein’s legal team has gagged them with a nondisclosure agreement. They travel to California, London, and Wales to interview sources, trying to compel witnesses to “use your experience to help other people.” Still, no luck. Among the exceptions is Zelda Perkins, a former Weinstein employee from the early 1990s, played by Samantha Morton (among the first actors to call out Weinstein for not casting her in Terry Gilliam’s The Brothers Grimm because he didn’t find her attractive enough). Zelda confronted Weinstein about Rowena Chiu (Angela Yeoh), another assistant whom he assaulted, and when they asked for Miramax to correct his behavior, they were forced to sign NDAs with absurdly restrictive conditions. Soon, the sheer number of settlements and NDAs uncovered by Twohey and Kantor reflects a pattern of behavior, yet the issue of finding a quotable source remains challenging.

But as Kantor has already discovered, many of those who have had experiences with Weinstein refuse to go on the record, either out of fear, no desire to relive their trauma, or because Weinstein’s legal team has gagged them with a nondisclosure agreement. They travel to California, London, and Wales to interview sources, trying to compel witnesses to “use your experience to help other people.” Still, no luck. Among the exceptions is Zelda Perkins, a former Weinstein employee from the early 1990s, played by Samantha Morton (among the first actors to call out Weinstein for not casting her in Terry Gilliam’s The Brothers Grimm because he didn’t find her attractive enough). Zelda confronted Weinstein about Rowena Chiu (Angela Yeoh), another assistant whom he assaulted, and when they asked for Miramax to correct his behavior, they were forced to sign NDAs with absurdly restrictive conditions. Soon, the sheer number of settlements and NDAs uncovered by Twohey and Kantor reflects a pattern of behavior, yet the issue of finding a quotable source remains challenging.

Schrader, the German filmmaker behind I’m Your Man (2021) and Netflix’s Unorthodox (2020), handles the film with a confident hand and crisp images by cinematographer Natasha Braier. If there’s a misstep in the proceedings, it’s when Schrader takes the viewer into flashbacks of certain victims. For instance, the film opens in 1992, in Ireland, when Laura Madden (later played by Jennifer Ehle) lands herself a job on a Miramax production, only to find herself running down the street in tears after her crushing encounter with Weinstein. Schrader also shows other victims’ recollections, such as a young Perkins feeling alienated at a party after being forced to sign an NDA by Weinstein’s attorneys. While it’s powerful to see how these women reacted at the moment, these scenes feel removed from the grounded journalistic reporting that drives the story. More poignant are verbal accounts that force the audience to watch these characters relive their experiences—such as Madden’s retelling of what happened to her. Ehle’s performance as Madden, who has been scarred by her experience and is facing breast cancer treatments when she’s contacted by Kantor, is a show-stealer. Schrader sets her account against a montage of images from the uninhabited hotel room and shower where her assault took place, and the pain of this sequence is bottomless.

Mulligan and Kazan occupy their roles with pathos to spare. Beyond their journalistic duties, their realization of just how deep the systemic problem goes becomes staggering and personally impactful. Twohey makes a call to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a federal organization designed to protect people, but finds that due to bureaucratic nonsense, the system cannot give out information about the volume of harassment claims filed against Weinstein or Miramax. Mulligan is excellent at playing Twohey as a no-bullshit reporter who’s tired of uncovering systems that protect abusers—including members of the media who were promised celebrity interviews by Weinstein if they remained quiet about his scandals. “He built the silence,” explains a former Miramax executive. And sure enough, Twohey and Kantor are made to feel followed and threatened by the looming influence of Weinstein goons. But the reporters remain steadfast, if not unshaken. Twohey’s anger comes to a deeply satisfying head when she responds to an unwanted advance at a bar with a fierce “Fuck you!” that received cheers at my screening.

She Said recounts much of the information and several recorded statements made by those involved in the original story and subsequent book. Those who kept up with the news at the time probably won’t learn much new information, although the film ends with a victorious postscript about the impact of Twohey and Kantor’s reporting and the reckoning that followed the popularization of Tarana Burke’s famous hashtag. And even though the film avoids addressing some of the racial and gender biases around #MeToo that make it more difficult for women of color and men to speak out about abuse, the film unabashedly honors the work that led up to the lightning-strike article in the New York Times. She Said relies on potent stories by quoted witnesses, and the extent of Weinstein’s abusive and coercive tactics is enough to make the viewer enraged and saddened that it went on for so long all over again. Even though Schrader adheres to the familiar beats of investigative reporting movies, she does so with such confidence and clarity that one can hardly fault its effective narrative structure. Instead, the film will stand as an accessible and stirring reminder to have the courage to speak up and call out abuse when it occurs.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review