Reader's Choice

Rope

By Brian Eggert |

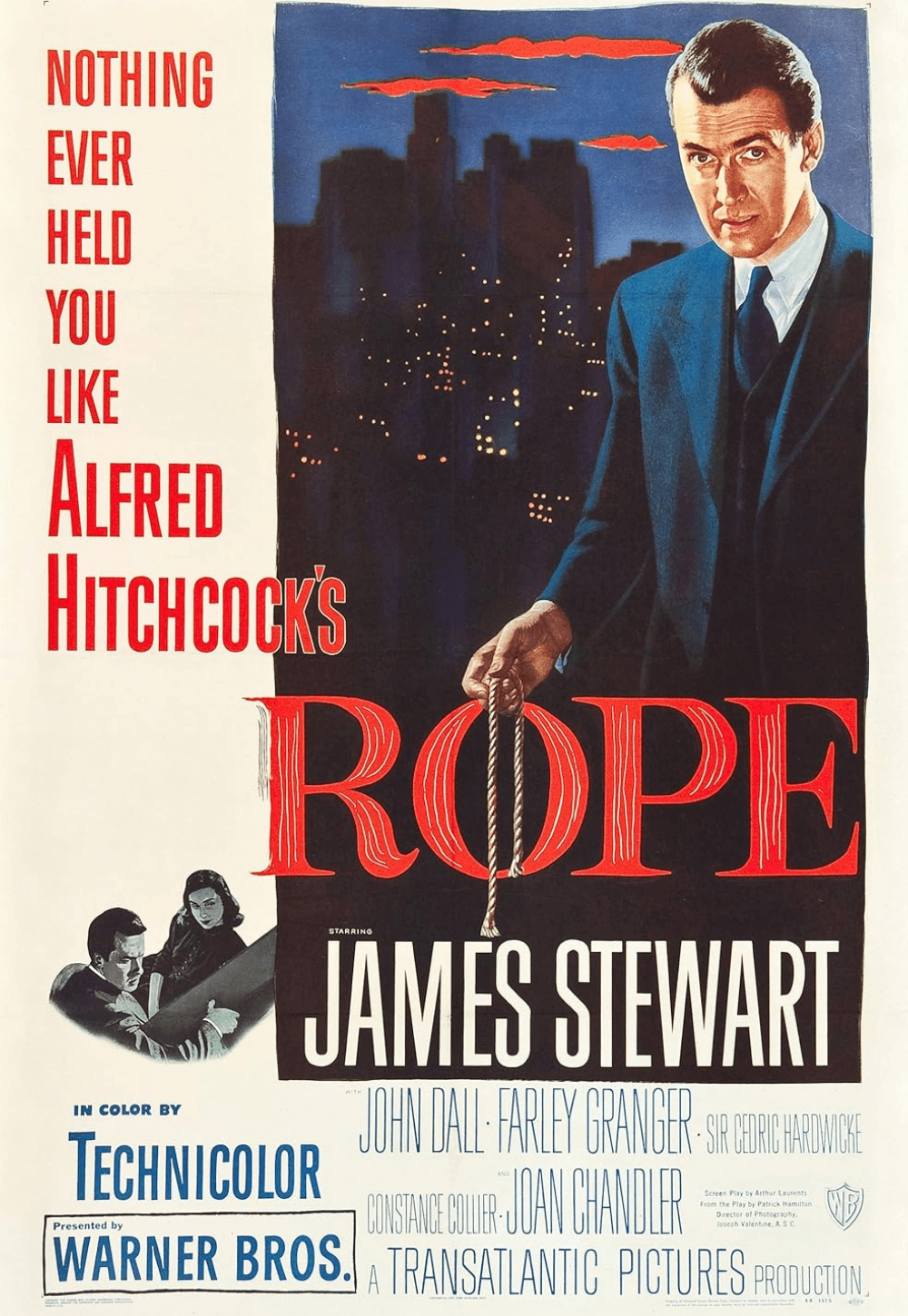

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope is a unique experiment. It emerged from a pivotal moment when the director shifted between major studio partnerships and gained newfound creative freedom. Made during a transitional period that found him just free of the contract with taskmaster producer David O. Selznick that had brought him to Hollywood, and just before entering two long partnerships with Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures, the 1948 release found Hitchcock embarking on a production that marks several firsts for him. On Rope, he served as producer for the first time, working alongside Sidney Bernstein under their short-lived production company, Transatlantic Pictures. Rope would be one of two features made entirely by the company, along with Under Capricorn (1949). The latter was such a financial disaster that Hitchcock and Bernstein had to dissolve Transatlantic, which had already begun developing Stage Fright (1950) and needed Warner Bros. to assist. Rope was also Hitchcock’s first color feature, his first film that attempted to replicate a work of stage drama, and his first experiment in reel-long takes upwards of ten minutes—a gimmick that had interested him for years and which Rope, with its single setting in a Manhattan apartment, could facilitate. Yet, this lesser-celebrated feature by the Master of Suspense remains one of his most fascinating pictures because it aligns with his thematic interests yet deviates from his usual formal methods.

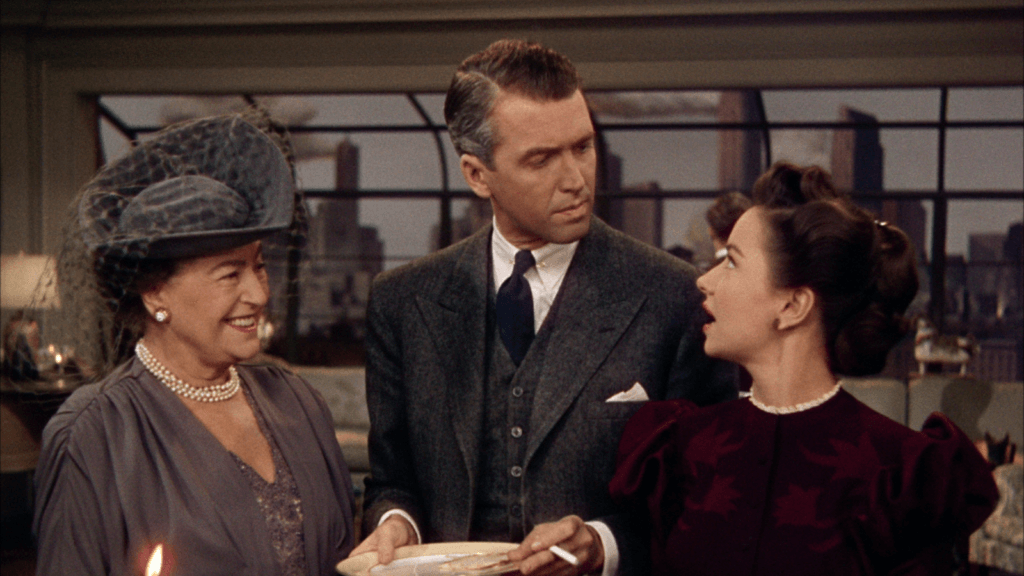

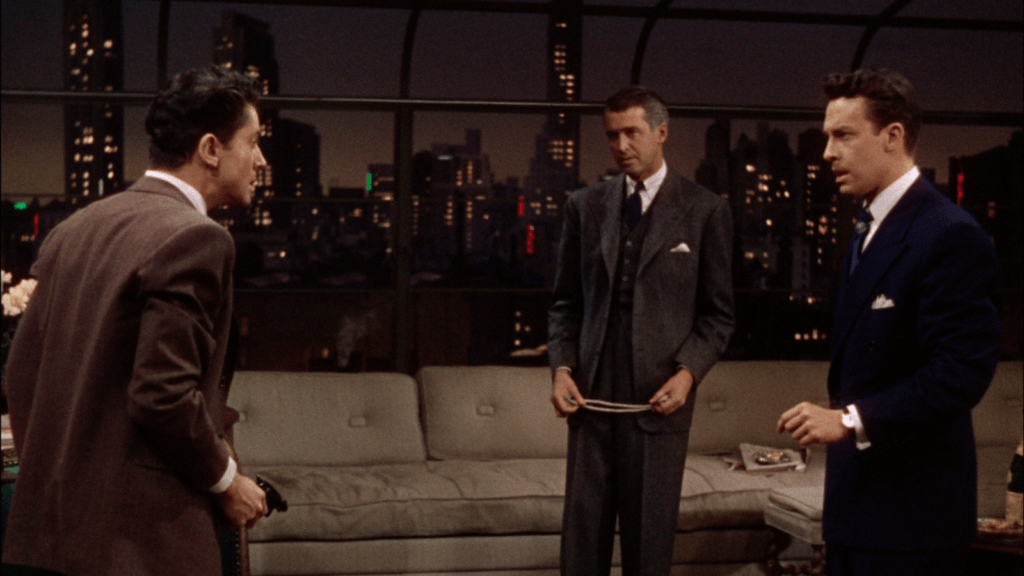

John Dall and Farley Granger play Brandon and Phillip, who, in the first scene, strangle their friend David (Dick Hogan) in their apartment with a length of rope and place his body in a wooden drawing room chest. Believing they have committed a perfect murder, they follow their killing with a small get-together arranged by Brandon. In attendance are David’s girlfriend Janet (Joan Chandler) and her ex-boyfriend Kenneth (Douglas Dick), making for an awkward reunion. But with David out of the way, Brandon predicts it will mean a renewed love connection. The victim’s father, Mr. Kentley (Sir Cedric Hardwicke), plans to examine some rare books. He brings along his sister-in-law, the superstitious Mrs. Atwater (Constance Collier), who offers much absent-minded comic relief. Last to arrive is Brandon and Phillip’s former instructor, Rupert Cadell (James Stewart), a humorously macabre sort who likes to wax philosophical about murder. With a facetious wit, he claims he “approves of” murder to resolve societal problems. In a proposal that sounds eerily like The Purge franchise, Rupert even promotes seasons of killing, albeit only for the “privileged”—an ideology that sounds too close to Nazism for Mr. Kentley’s liking. Rupert’s lessons have been picked up and warped by Brandon and Phillip, who respond to their murder differently—with guilt and anxiety threatening to consume Phillip, while Brandon remains chillingly calm. Amplifying the tension, Brandon awkwardly displays their buffet on the chest with David’s body inside.

Based on Patrick Hamilton’s 1929 stage play, the film was adapted with the help of two writers. First, there was Hume Cronyn, star of the director’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Lifeboat (1944), who worked closely with Hitchcock to get the screen story right. Hamilton had based his play on Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two intelligent gay men who became obsessed with Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch while attending the University of Chicago. Determined to prove themselves living embodiments of the theory, they set out to execute the perfect murder, only to make several blunders that, ultimately, earned them both life sentences. Hitchcock had followed the original story and Hamilton’s play for years. The account was too twisted for other Hollywood producers who were sure the censors would cut into the material. But after working out the screen story with Cronyn, Hitchcock hired playwright and screenwriter Arthur Laurents to adapt the material into a screenplay, knowing that his own name-above-the-title reputation would help smooth out any disputes with censors.

Hitchcock wanted Laurents partly because of his relationship with Granger, an open secret in Hollywood. The director wanted Granger to play Phillip for that same reason. Hitchcock reportedly never mentioned Laurents and Granger’s affair to them, and without spelling it out, the director implied to Laurents that he wanted Brandon and Phillip’s sexuality hinted at in the film. Of course, the studios and censors wouldn’t allow any direct references. But as Laurents wrote in his memoir: “It’s there; you have to look but it’s there all right.” Brandon and Phillip seem to live together in the same New York apartment, often bickering like an old married couple. And when Phillip claims he doesn’t eat meat, Janet remarks, “How queer.” The mostly negligible and cliché signifiers established a pattern in Hollywood movies that, for years, associated queerness with murderers and deviants. A similar theme permeates Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), leading to movies such as Cruising (1980), Dressed to Kill (1980), The Silence of the Lambs (1991), and Basic Instinct (1992). While none of these examples directly makes a grand statement linking queerness to murderous impulses, their cumulative effect perpetuated harmful associations that the LGBTQ+ community would protest.

For his part, Hitchcock felt he could overcome any censorship concerns with his casting. During pre-production, the director envisioned Cary Grant, a speculated bisexual, in the leading role as Rupert, who, in the original play, was more evidently gay. This supplied an allusion to an earlier relationship between Rupert and Brandon—the role for which Hitchcock wanted Montgomery Clift, another gay actor. Grant and Clift both turned down their proposed roles, worrying that they might be accused or exposed. John Dall took the Brandon role, while James Stewart—a new, darker model since returning from the war shaken by what he had seen—would play Rupert. However, everyone involved suspected that the somewhat naïve Stewart didn’t know his character was gay; after all, Stewart rarely exuded any inkling of sexuality one way or another. Still, his presence gave Rope a marquee name and also supplied Hitchcock with an opportunity to explore his penchant for meta-humor. Note when Mrs. Atwater refers to seeing a movie: “The Wonderful something,” she says, nodding to Stewart’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Then she references an Ingrid Bergman film—“Just Something”—hinting at Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946).

Beyond the insider humor, Hitchcock and his writers changed much about Hamilton’s play, altering locations, updating character names, and swapping one trope for another. The Chicago location became New York. A snooty French manservant became one of Hitchcock’s favorite types, the kindly old maid, Mrs. Wilson (Edith Evanson), adding a touch of innocence and humor to the macabre situation. She’s also central to the film’s most suspenseful scene—when she clears the spread from the chest containing David’s body and intends to load books inside. The camera remains on Mrs. Wilson, watching her from a position that peers down the apartment’s long hallway. While everyone else discusses David’s whereabouts, Mrs. Wilson gets ever closer to opening the chest, fastened shut with an unreliable lock. This leads to an incredibly close call, with Brandon and Phillip nearly exposed. The sequence, along with a neon sign in the background that flashes the word “STORAGE,” serve as literal and subliminal reminders of the body hidden in the chest.

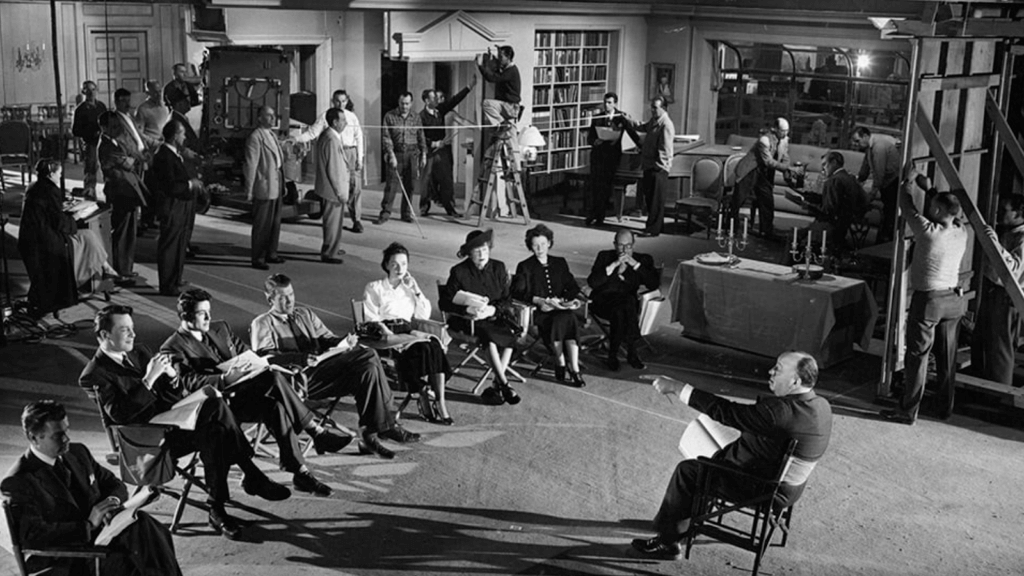

Hitchcock also adjusted his style for Rope’s aesthetic conceit. Rather than his usual mode of cutting for effect—evident since the cross-cutting in his debut film, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927)—the director conceived elaborate camera movements on an ambitious set to accomplish his vision. Hitchcock wanted the film to compliment the stage version, which had been a continuous story, with no breaks or intermissions. Once the curtain went up on the story, it didn’t come down until the story was over. The director sought to shoot the picture in “reel” time, he told Favius Friedman for Popular Photography, with unbroken reels of footage. Using rather clumsy verbal imagery, he remarked that the camera would be “devouring the action like a giant steam shovel.” With each reel containing about nine minutes of footage and 950 feet of film, Hitchcock planned out around 25 camera movements per reel.

Whereas his usual visual agenda embraced montage and relied on editing and camera movements working in harmony, the director had to rethink that approach for Rope. Instead of cutting from master shots to close-ups, these transitions had to be achieved by maneuvering the camera from one setup to the next, sometimes with rather wobbly movements given the massive three-strip Technicolor cameras. The production required the crew to develop a special floor that would allow the cameras to move silently without ruining the sound. The camerawork was carried out by two cinematographers: Hitchcock’s regular collaborator Joseph Valentine (Saboteur, 1942), who eventually left the production after proving unable to work in color. He was reported “ill,” and replaced by Technicolor specialist William V. Skall (Quo Vadis, 1951). However, Hitchcock noted at the time that color’s role in the film was largely to underscore the details in the background.

Indeed, Hitchcock went to incredible lengths to realize the details seen through the vast windows of his apartment set overlooking the Manhattan skyline. The collapsible space includes a reception room, hallway, and kitchen. A vast window in the reception room shows the gradual setting of the sun as the story progresses. Hitchcock was known to boast about the fine details of the 12,000 square feet stage, the largest ever used at the time, which included skyline miniatures consisting of hundreds of tiny windows, false smoke billowing up from the chimneys, and small neon signs. Like a model train enthusiast gushing over the fine details, the director made much of the spun glass clouds, which adjust eight times throughout the nine reels. They also show the setting sunlight in a striking, ever more orange hue. For all of these details, the timing had to be perfect. Hitchcock called it “a miracle of cueing.” The film took around twenty days to shoot its nine reels, with additional days for reshoots, preceded by ten days of rehearsing the material with the cameras and lighting to ensure they could nail the required timing. Despite the preparation and exactitude, Hitchcock relies on inelegant solutions to disguise his cuts, such as pushing the camera into a character’s back in a faux fade-to-black.

If the transitions from one reel to another prove conspicuously concealed, the story fares somewhat better. Hitchcock situates his macabre scenario in a familiar and domestic environment, as he did in Sabotage (1936), Shadow of a Doubt, and The Trouble with Harry (1955). The homey backdrop accentuates Phillip’s nervy behavior, as does his piano performance of Francis Poulenc’s Mouvements Perpétuels—music that starts oppressively cheery but winds around to sound almost discordant and nightmarish as it goes. Brandon and Phillip remain fascinating characters, the former a remorseless psychopath whose nerves fray around Rupert alone, the latter rocked with anxiety over the cat-and-mouse game as Rupert begins to suspect them—particularly when Rupert exposes that Phillip has strangled chickens before. Less convincing is Rupert, who, though played with Stewart’s pure charm and tense suspicion, goes from proposing casual murder for an elite few to censuring his former students for carrying out his ideas. He condemns them, shouting, “Did you think you were God, Brandon? Is that what you thought when you choked the life out of [David]?” Rupert suddenly realizes the value of human life and proclaims, “Now I know that we are each of us a separate human being, Brandon. With the right to live and work and think as individuals, but with an obligation to the society we live in.” Even so, after learning that lesson and setting aside his macabre philosophy, Rupert seems to delight in the certainty that they will receive the death penalty. “You’re going to die!” he declares with moral conviction, having condemned murder but endorsed capital punishment.

The actors and scenario do much to elevate Rope and its sometimes uneven ideas, while Hitchcock’s formal strategy ranges from inspired to ungainly. Much of what remains so intriguing about the film are the production design’s details and the extratextual work that made the single setting a reality. In his legendary interview with François Truffaut, Hitchcock confessed that Rope was a “stunt” that “was quite nonsensical because I was breaking with my own theories on the importance of cutting and montage for the visual narration of a story.” Later, he would remark, “I really don’t know how I came to indulge in it.” Critics agreed. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the picture a “novelty” and “rather thin.” Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times summed up the appeal: “The interesting experimental values in this Hitchcock production could never be denied, yet I would not rate it one of his best.” To be sure, Rope is more than an interesting failure. The experience contains genuine moments of suspense and, at 83 minutes, breezes by thanks to the mostly fluid camerawork and convincing performances. Setting aside what the script lacks in character logic and how the formal agenda sometimes distracts from rather than serves the story, Rope remains only middling by the high benchmark set by Hitchcock’s body of work.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on August 31, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Krohn, Bill. Hitchcock At Work. Phaidon, 2000.

Laurents, Arthur. Original Story By: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood. Applause, 2001.

McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books, 2003.

Modleski, Tania. The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory. Routledge, 2006.

Petrie, Graham. Hollywood Destinies: European Directors in America, 1922-1931. Wayne State University Press, 2002.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. The Men Who Made the Movies: Interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A. Wellman. Atheneum, 1975.

Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. With the collaboration of Helen G. Scott. Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Žižek, Slavoj. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock). Verso, 1992.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review