The Definitives

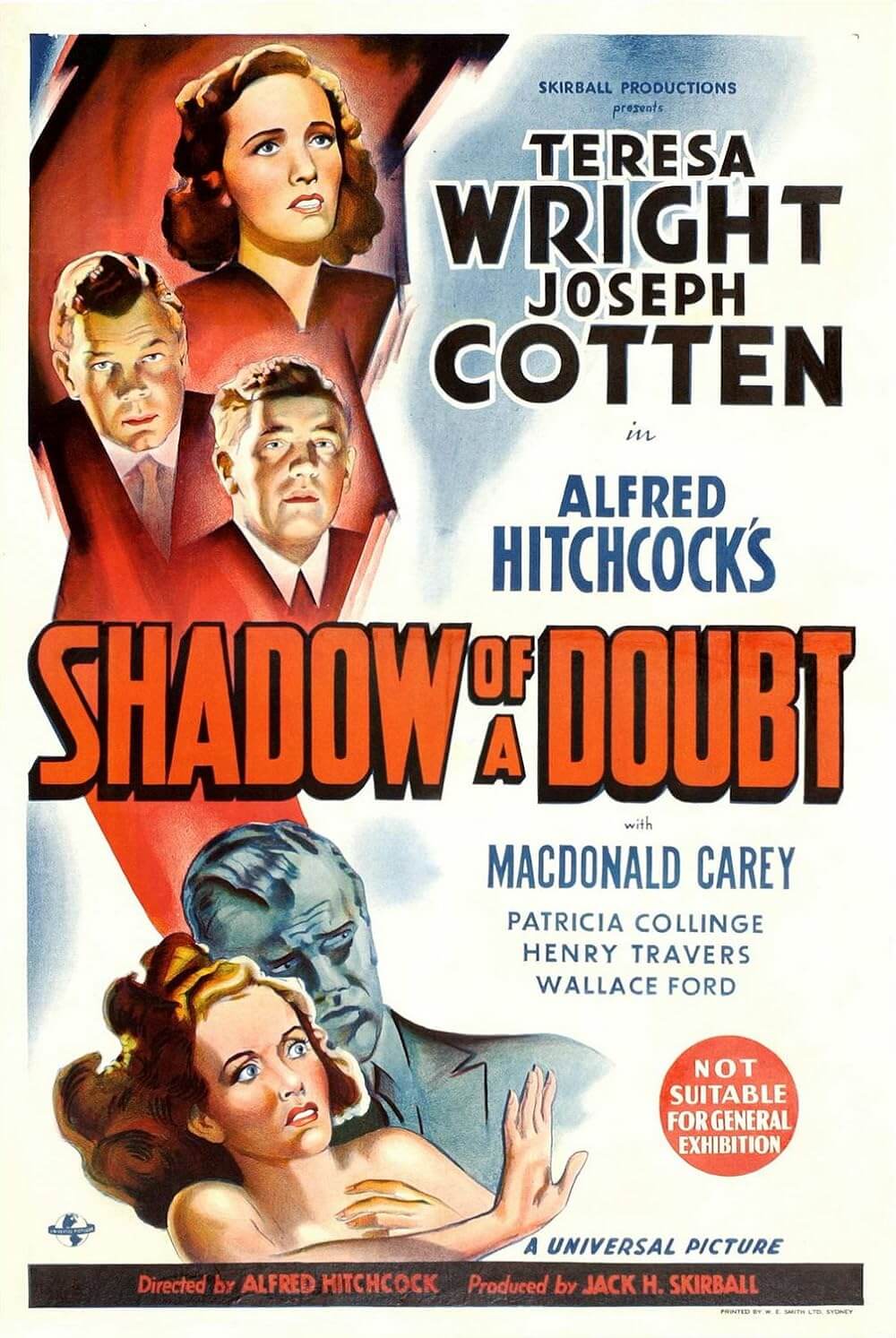

Shadow of a Doubt

Essay by Brian Eggert |

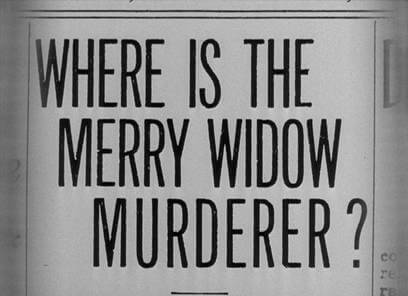

Uncle Charlie has come home, much to the delight of Charlotte, otherwise known as Young Charlie, nicknamed after her uncle. She idolizes him and expects his presence will break up the monotonous routine of her dull, predictable family members. Visiting his sister in the picturesque Santa Rosa, California, an idyll of small-town America, Uncle Charlie sits down for the customary family dinner. Usually, Young Charlie couldn’t be happier to see her uncle, except she suspects him of something awful after he hides a newspaper headline about The Merry Widow Murderer, the killer strangling lonely rich widows in cities along the East Coast. At the mere notion of city women, Uncle Charlie goes off: “The cities are full of women, middle-aged widows, husbands dead, husbands who’ve spent their lives making fortunes, working and working. And then they die and leave their money to their wives. Their silly wives. And what do the wives do, these useless women? You see them in the hotels, the best hotels, every day by the thousands. Drinking the money, eating the money, losing the money at bridge. Playing all day and all night. Smelling of money. Proud of their jewelry but of nothing else. Horrible, faded, fat, greedy women.” Young Charlie interjects, “They’re alive. They’re human beings!” Uncle Charlie wonders “Are they? Are they human or are they fat, wheezing animals, hmm? And what happens to animals when they get too fat and too old?” Indeed, Uncle Charlie is the killer his niece suspects him to be.

By introducing a murderer into the average American home, Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt refines the director’s most persistent theme down to its essential components: The prevailing notion that something dark lurks underneath the surface of things exists in nearly each Hitchcock film. As a plot device, it’s found in tales of espionage where seemingly respectable men of some notoriety, often a professor or gentleman, turn out to be an enemy spy; in his thrillers where the wrong man is accused of a crime; horror stories in which birds go mad; when a priest must remain tight-lipped about a murder; as the justice system points its finger at an innocent man; long after a boy turns on his best-friend mother; in a church that doubles as a den of spies; when a doppelganger isn’t a double at all but part of an elaborate con game. The examples in Hitchcock’s more than fifty film career are countless, but few cultivate the theory into its most basic form as this 1943 release. Often cited as his favorite of his own films thanks to the ever-enthusiastic marketing department of the distributors at Universal Pictures, the director clarified in his series of interviews with François Truffaut how Shadow of a Doubt remained merely “one of his favorites”. To be sure, there are better Hitchcock pictures with greater chills, tighter plotting, and richer visual bravado. But, at least theoretically, few define in concept alone what makes one of his films pointedly Hitchcockian.

The story takes place in 1941, presumably before the attack on Pearl Harbor brought America into World War II. Leaving a trail of victims behind him, Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) wires his sister Emma Newton (Patricia Collinge) in Santa Rosa that he intends to pay a visit. At the same time, Young Charlie (Teresa Wright) finds herself wishing for her Uncle Charlie to interrupt her family’s conventional little lives. Fate seems to bring them together, only to drive a spike between them when Young Charlie starts to suspect something’s wrong with her dear uncle, beginning with how he hides the newspaper clippings on the Merry Widow Murderer. Later, two detectives (Macdonald Carey and Wallace Ford) posing as national survey takers want to interview everyone in the Newton house, but Uncle Charlie refuses to participate, or even allow his picture to be taken. And then there’s his deviously catatonic speech about useless old widows. When Young Charlie’s suspicions are confirmed during a confrontation with her uncle, she comes to find herself barely surviving a series of near-death accidents, no doubt arranged by her Uncle Charlie. With detectives sniffing about and his niece knowing too much, Uncle Charlie announces he must leave town by train, arranging himself a local widow for the ride. He invites Young Charlie aboard to see him off and keeps her there as the train departs. During a struggle where her uncle tries to throw her from the moving locomotive, Young Charlie turns and her uncle falls off to meet his death by an oncoming train. Despite his murders, Young Charlie keeps her uncle’s secrets and Santa Rosa’s citizens honor him with a lavish funeral.

The story takes place in 1941, presumably before the attack on Pearl Harbor brought America into World War II. Leaving a trail of victims behind him, Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) wires his sister Emma Newton (Patricia Collinge) in Santa Rosa that he intends to pay a visit. At the same time, Young Charlie (Teresa Wright) finds herself wishing for her Uncle Charlie to interrupt her family’s conventional little lives. Fate seems to bring them together, only to drive a spike between them when Young Charlie starts to suspect something’s wrong with her dear uncle, beginning with how he hides the newspaper clippings on the Merry Widow Murderer. Later, two detectives (Macdonald Carey and Wallace Ford) posing as national survey takers want to interview everyone in the Newton house, but Uncle Charlie refuses to participate, or even allow his picture to be taken. And then there’s his deviously catatonic speech about useless old widows. When Young Charlie’s suspicions are confirmed during a confrontation with her uncle, she comes to find herself barely surviving a series of near-death accidents, no doubt arranged by her Uncle Charlie. With detectives sniffing about and his niece knowing too much, Uncle Charlie announces he must leave town by train, arranging himself a local widow for the ride. He invites Young Charlie aboard to see him off and keeps her there as the train departs. During a struggle where her uncle tries to throw her from the moving locomotive, Young Charlie turns and her uncle falls off to meet his death by an oncoming train. Despite his murders, Young Charlie keeps her uncle’s secrets and Santa Rosa’s citizens honor him with a lavish funeral.

The idea for Shadow of a Doubt was first proposed to Hitchcock while he was making Saboteur (1942). During this period in his career, the director frequently lined up material for his next picture while in production on another. Hitchcock heard the basic outline as conceived by author Gordon McDonnell over lunch. McDonnell was the husband of David O. Selznick’s story editor Margaret McDonnell, and his idea, originally called “Uncle Charlie”, featured a cliffhanger ending where the titular character lunges at his niece and plunges himself off a cliff. Interested, Hitchcock asked McDonnell for a synopsis and received a 9-page treatment, and although he asked for an elaborated version, McDonnell never produced it. Nevertheless intrigued, the story reminded Hitchcock of the Parisian con artist and murderer Henri Landru, a killer of ten women and one boy between 1915 and 1919, who was eventually caught executed by guillotine in 1921. Landru would also be the inspiration for Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux in 1947 and Claude Chabrol’s Landru in 1962. To adapt the material, Hitchcock sought out playwright Thornton Wilder to assist him and wife Alma Reville on the screenplay. Wilder, a Pulitzer Prize winner for The Bridge of San Luis Rey, also won the Pulitzer for Our Town, a similarly themed tale about looking into the underbelly of an average American town. Just a few years before, Hitchcock had come from Britain, where he had access to all the best stars and writers; ever since coming to Hollywood, he loathed that U.S. studios rarely afforded him the opportunity to work with proven talent. Wilder represented a refreshing change in this respect, and he received special notice in the film’s opening credits that acknowledge his director’s appreciation.

But Wilder was only contracted to assist on the script until he shipped out for military duty one month later, and even with long writing sessions beside Hitchcock, they did not complete the script together. Wilder contributed much to the story’s seedier aspects, specifically Uncle Charlie’s long speeches about those “fat, greedy women”, as well as the plot’s structure. Wilder also suggested the opening scene where Uncle Charlie lies awake on his bed in a New Jersey boarding house, smoking and mulling over the two badges waiting outside to catch him. The idea, borrowed from Hemingway’s The Killers, served this story well and justified Hitchcock’s own penchant for borrowing a little inspiration from other material, yet using it resourcefully. Wilder proposed a replacement (his friend and playwright Robert Audrey), but Hitchcock felt he needed to lighten Wilder’s often darker instincts, and he chose Sally Benson to produce a rewrite. Benson’s book Junior Miss, following the romantic meddlings of a 12-year-old girl, had just been turned into a play, which Hitchcock enjoyed. Benson’s draft added a greater sense of humor and modern community to Santa Rosa and altered the Newton family dynamic. Actress Patricia Collinge was also a talented playwright and expanded her character to make Emma less a silly social climber and more vulnerable. In all, six writers contributed to Shadow of a Doubt: McDonnell, the Hitchcocks, Wilder, Benson, and Collinge. Given this writerly input, it seems atypical that the plot and tone feel so cohesive.

But Wilder was only contracted to assist on the script until he shipped out for military duty one month later, and even with long writing sessions beside Hitchcock, they did not complete the script together. Wilder contributed much to the story’s seedier aspects, specifically Uncle Charlie’s long speeches about those “fat, greedy women”, as well as the plot’s structure. Wilder also suggested the opening scene where Uncle Charlie lies awake on his bed in a New Jersey boarding house, smoking and mulling over the two badges waiting outside to catch him. The idea, borrowed from Hemingway’s The Killers, served this story well and justified Hitchcock’s own penchant for borrowing a little inspiration from other material, yet using it resourcefully. Wilder proposed a replacement (his friend and playwright Robert Audrey), but Hitchcock felt he needed to lighten Wilder’s often darker instincts, and he chose Sally Benson to produce a rewrite. Benson’s book Junior Miss, following the romantic meddlings of a 12-year-old girl, had just been turned into a play, which Hitchcock enjoyed. Benson’s draft added a greater sense of humor and modern community to Santa Rosa and altered the Newton family dynamic. Actress Patricia Collinge was also a talented playwright and expanded her character to make Emma less a silly social climber and more vulnerable. In all, six writers contributed to Shadow of a Doubt: McDonnell, the Hitchcocks, Wilder, Benson, and Collinge. Given this writerly input, it seems atypical that the plot and tone feel so cohesive.

Much as he wanted to do with Cary Grant, Hitchcock had long desired to cast audience favorite William Powell in a murderous role. Often in comic good-guy parts, Powell had long resisted the idea so as not to tarnish his image as the detective from both the Philo Vance series and lovable The Thin Man franchise, but Hitchcock’s recent successes changed the actor’s mind. This made no difference to MGM, who refused to lend out Powell to play Uncle Charlie. Likewise, Joan Fontaine and her sister Olivia de Havilland were considered for Young Charlie, yet both proved to be unavailable. While the casting conundrum continued, Hitchcock began to shoot backgrounds and footage with the detectives on Uncle Charlie’s trail. Without a leading man, the director filmed the opening chase sequence three times using tall, medium, and short stand-in actors shot from behind or from a distance; when the rather tall Joseph Cotten was ultimately cast as Uncle Charlie, Hitchcock used the tall man version of this sequence, and later cut in scenes where Cotten’s face was visible. At this point, Cotten, a Mercury Theater Player, was new to film but was made popular by Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) and had just finished filming Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, which Hitchcock demanded to see prior to its release for further evidence of Cotten’s talent. When the two met to discuss the part, Cotten asked Hitchcock about the nature of Uncle Charlie, and the director explained that the actor should not put on airs. Hitchcock told Cotten he should just be himself—murderers look and act like everyone else. After all, if they were so easy to spot, we’d notice them walking down the street. The very thesis of Shadow of a Doubt is to illustrate that anyone, even a loved one, could have a killer inside them.

Less than three months after Hitchcock heard McDonnell’s synopsis for the first time, shooting started in July of 1942, which should offer some idea of how quickly the Master of Suspense conceived a picture in his mind, fleshed out the script, storyboarded, and started shooting from those models. At the time, the War Production Board issued a $5,000 limit on Hollywood set building to preserve material for the war effort. For the first time since his early years in Britain, Hitchcock, a director famous for his use of controlled sets, was forced to shoot on location to limit his set budget. The postcard-perfect Santa Rosa rested in a sleepy section of northern California not far from Hitchcock’s home. Its population of around thirteen thousand lived in quiet homes with red front doors and white picket fences, the community surrounding a central square where nearly everyone showed up during the filming of Uncle Charlie’s funeral scene. The location was selected not only because the story demanded it, but because it was wine country, and Hitchcock was a wine fanatic of sorts. After shooting, he often went to nearby vineyards to sample grapes off the vine. At the same time, Hitchcock’s mother was gravely ill; restrictions on international travel prevented him from visiting her, and she died that September. An argument could be made that the prolonged illness and eventual death of Hitchcock’s mother during the shoot offered the filmmaker a certain sentimentality toward the Newton home in the film, which makes Uncle Charlie’s potential interruption of that familial unity all the more dreadful.

Less than three months after Hitchcock heard McDonnell’s synopsis for the first time, shooting started in July of 1942, which should offer some idea of how quickly the Master of Suspense conceived a picture in his mind, fleshed out the script, storyboarded, and started shooting from those models. At the time, the War Production Board issued a $5,000 limit on Hollywood set building to preserve material for the war effort. For the first time since his early years in Britain, Hitchcock, a director famous for his use of controlled sets, was forced to shoot on location to limit his set budget. The postcard-perfect Santa Rosa rested in a sleepy section of northern California not far from Hitchcock’s home. Its population of around thirteen thousand lived in quiet homes with red front doors and white picket fences, the community surrounding a central square where nearly everyone showed up during the filming of Uncle Charlie’s funeral scene. The location was selected not only because the story demanded it, but because it was wine country, and Hitchcock was a wine fanatic of sorts. After shooting, he often went to nearby vineyards to sample grapes off the vine. At the same time, Hitchcock’s mother was gravely ill; restrictions on international travel prevented him from visiting her, and she died that September. An argument could be made that the prolonged illness and eventual death of Hitchcock’s mother during the shoot offered the filmmaker a certain sentimentality toward the Newton home in the film, which makes Uncle Charlie’s potential interruption of that familial unity all the more dreadful.

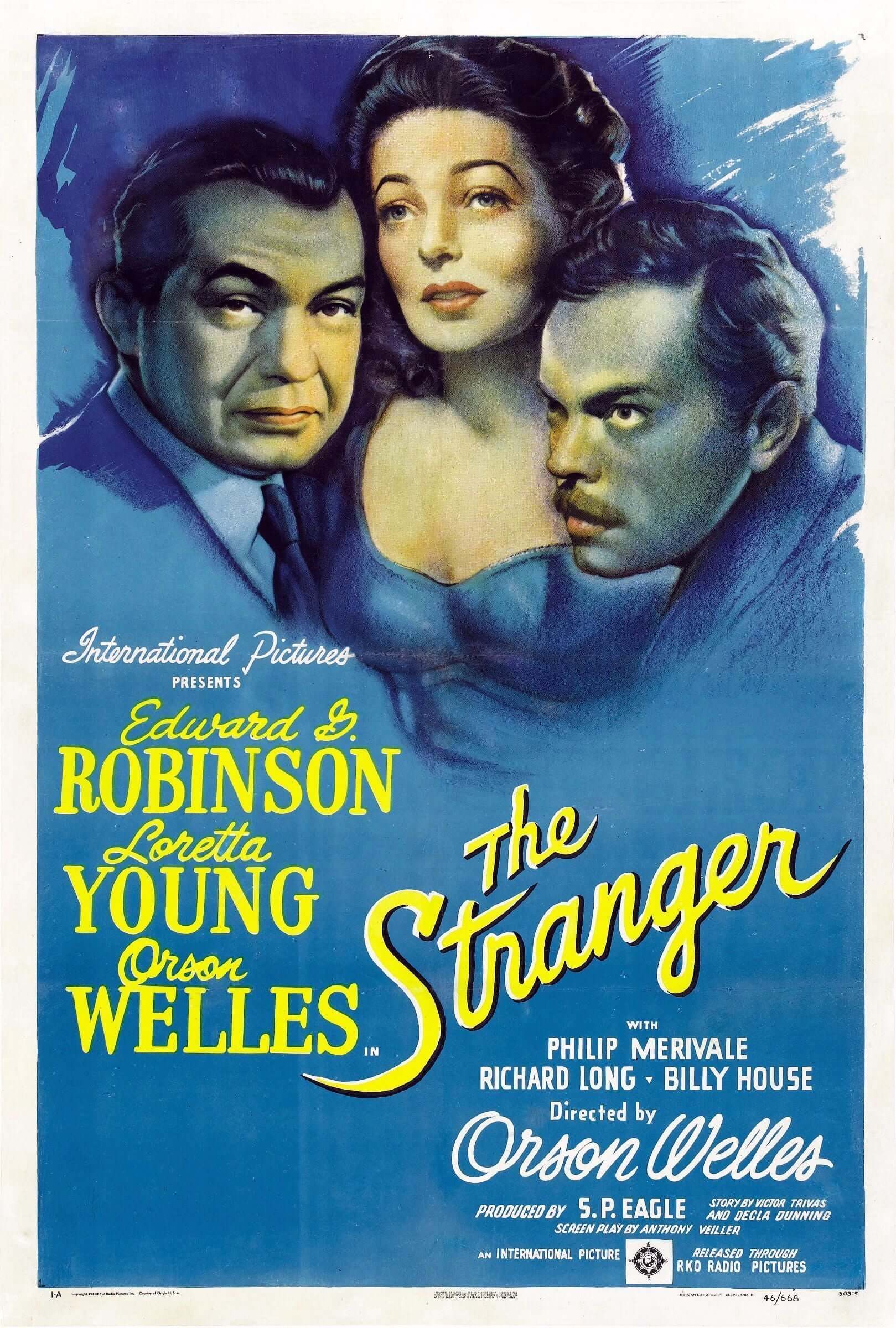

Hitchcock’s vision of Anytown, USA looks and feels like a Norman Rockwell painting for the Saturday Evening Post. Santa Rosa is gorgeous, clean, and intentionally corny, almost to the point of satire. How curious then that Hitchcock shot, for the most part, on location. Much in terms of realism is sacrificed for this syrupy effect, beginning with the two detectives who, apparently unbound by jurisdictional regulation, follow Uncle Charlie across the continental United States to get their man. Meanwhile, Detective Jack Graham (Carey) gradually makes his romantic intentions clear toward the uncertain Young Charlie, who, in spite of the Detective’s boyishness, remains far too young to be courted by an adult. The qualities that make the film’s depiction of both Santa Rosa and the Newton family into the embodiment of wholesomeness work as deliberate ideals if only so Hitchcock can shatter them. His is not the sentimentalized view that Americans remembered their pre-Pearl Harbor country to be; rather, the film suggests the world has always been filled with horrible people. Three years later, this same concept was repeated in Orson Welles’ The Stranger, a yarn about a post-WWII Nazi who escapes only to settle down in a sleepy American suburbia—the paranoid suggestion being that even though the Nazis were defeated, there was still danger in our seemingly safe communities. Both Hitchcock and Welles sought to clash against blindly optimistic views of small-town America and expose the seedy underbelly. Some forty years later, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet would achieve a similar effect through a dreamy, deeply symbolic treatment driven by the very same desire to address the darker side of small-town America.

Hitchcock uses similar symbolic touches to explore this dark side of America, although in far more subtle ways than Lynch’s film. As film historian Bill Krohn has pointed out, Hitchcock does much to underline a vampiric quality in Uncle Charlie, thus making Shadow of a Doubt a kind of abstract monster movie and therein critiquing American innocence of the period. We first see Uncle Charlie lying in bed during the day, the curtains closed, and the local landlady acting like a loyal vampiress. When he’s chased by the two detectives, they would seem to have cornered him, but the camera pulls back and Uncle Charlie has somehow escaped to a rooftop; satisfied with himself, he looks down and smokes a cigarette, without the slightest shortness of breath from the chase. On the train to Santa Rosa, he’s behind a black curtain in his sleeping berth, not to be disturbed; the train may as well be called the Demeter. When he arrives, the train appears under a cloud of black smoke, grim shadows looming over the station. He refuses to be photographed and has an unusual telepathic connection with his niece. At one point, one of the detectives tells Young Charlie’s little sister Ann (Edna May Wonacott) to busy herself by telling someone “the story of Dracula”. Originally, the line was “the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”. But Hitchcock changed the line, possibly to underline the parallel between Uncle Charlie and Dracula. Make of this what you will, but the suggestion that Uncle Charlie is some kind of monster becomes palpable within these hints.

Hitchcock uses similar symbolic touches to explore this dark side of America, although in far more subtle ways than Lynch’s film. As film historian Bill Krohn has pointed out, Hitchcock does much to underline a vampiric quality in Uncle Charlie, thus making Shadow of a Doubt a kind of abstract monster movie and therein critiquing American innocence of the period. We first see Uncle Charlie lying in bed during the day, the curtains closed, and the local landlady acting like a loyal vampiress. When he’s chased by the two detectives, they would seem to have cornered him, but the camera pulls back and Uncle Charlie has somehow escaped to a rooftop; satisfied with himself, he looks down and smokes a cigarette, without the slightest shortness of breath from the chase. On the train to Santa Rosa, he’s behind a black curtain in his sleeping berth, not to be disturbed; the train may as well be called the Demeter. When he arrives, the train appears under a cloud of black smoke, grim shadows looming over the station. He refuses to be photographed and has an unusual telepathic connection with his niece. At one point, one of the detectives tells Young Charlie’s little sister Ann (Edna May Wonacott) to busy herself by telling someone “the story of Dracula”. Originally, the line was “the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”. But Hitchcock changed the line, possibly to underline the parallel between Uncle Charlie and Dracula. Make of this what you will, but the suggestion that Uncle Charlie is some kind of monster becomes palpable within these hints.

In the original script outline, the Hitchcocks had considered putting more emphasis on a sexual tension between Uncle Charlie and Young Charlie; though most of the more obvious hints were removed, the implication still remains within the film. Undeniable is the connection between the two main characters and their referenced telepathic link prior to Uncle Charlie’s arrival in Santa Rosa. “We’re sorta like twins,” says Young Charlie, long before she begins to suspect her uncle of foul play. In the film’s opening scenes, the two speak to one another like affectionate lovers, and Young Charlie describes her relationship with him as “not just an uncle and a niece”. When Uncle Charlie begins to dole out gifts to the Newtons, his present to Young Charlie is a ring, which he delicately slips on her finger. Young Charlie refuses to even look at it, knowing it can only be perfect because it came from her dear Uncle Charlie. When they walk down the street together, her schoolmates look on with jealously, and Young Charlie, her arm under her uncle’s, seems to like him even more for the attention he brings her. After she discovers his secret, the betrayal feels less familial and more like that of an unfaithful lover. Not unlike the suggestion of Norman Bates’ incestuous feelings toward his mother, the central relationship between Uncle Charlie and Young Charlie enhances the power of the finale, his death, and the secret Young Charlie must keep.

Employing undertones in which Uncle Charlie is a vampire or where an incestuous link exists between his main characters effectively skews the world’s natural order or wholesomeness, which is what every great Hitchcock film does. Visually, the director used tilted angles to represent Uncle Charlie as part of an off-balance world. The director’s combination of stages and actual locations—his signature brand of cinematic realism—further emphasizes a world not entirely real and not completely safe. Hitchcock typically used master shots of actual locations, often landmark sites, which were later incorporated with sets replicating the locale. On Shadow of Doubt, the only major set-piece was a replica of the Newton house, which could be taken apart and moved to fit the director’s needs for off-kilter camera angles that represented the distorted world of the film. Shadow of a Doubt is a film filled with such archetypal Hitchcockian traits and visual flourishes, such as the long camera push onto Young Charlie’s ring—a moment anticipating the comparable but more bravado push onto the Unica key from Notorious (1946). He also incorporates much humor, such as the comic asides between Young Charlie’s father Joseph (Henry Travers) and his friend Herbie (Hume Cronyn) as they discuss the best ways to hypothetically murder one another. In a more ostentatious touch, Hitchcock uses a repetitive dream sequence throughout the film where, in Uncle Charlie’s mind, classicized dancers waltz to scorer Dimitri Tiomkin’s rendition of Franz Lehar’s “The Merry Widow Waltz”—an image both taunting to Uncle Charlie and haunting to the audience as it winds onscreen.

A tale whose specific time and place in history at once limit the film’s effect today yet renders it an emblematic work within Hitchcock’s career, Shadow of a Doubt does for the director’s prevailing theme and plot device what his Vertigo (1958) would later do for his sexual obsessions. Deliciously performed by Cotten, Uncle Charlie becomes a symbol of the very worst kind of American monster, while Wright’s decency is hopeful but never blind. Curious are the correlations and sexual underpinnings Hitchcock makes between them, and how that relationship develops not only between the characters, but through the subtext. Down-home American principles and Rockwellian suburban safety are confronted and disproved through the course of the story, told with chilling turns and surprises by the Master of Suspense. His later films, such as Strangers on a Train (1951) or I Confess (1953), deal with similar themes in more complicated, richly detailed, and entertaining ways, but they lack the singularity of this picture. As a result, the simplicity of its scenario might seem restrained next to the director’s more outright explorations such as Psycho (1960) or Frenzy (1972), but this plainness is essential to the film. A prototype of Hitchcock-brand storytelling, Shadow of a Doubt encapsulates what it means to be “an Alfred Hitchcock film” through broad strokes and basic values.

Bibliography:

Krohn, Bill. Hitchcock At Work. Phaidon, 2000.

McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books, c2003.

Petrie, Graham. Hollywood destinies: European directors in America, 1922-1931. Wayne State University Press, c2002.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. Atheneum, 1975.

Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. With the collaboration of Helen G Scott. Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Žižek, Slavoj. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock). Verso, 1992.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review