Priscilla

By Brian Eggert |

Early in Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla, Elvis Presley performs “Whole Lot of Shakin’ Going On” at a party, often directing his eyes to Priscilla Beaulieu, then a ninth-grader. It’s a pointed choice given that the song’s writer, Jerry Lee Lewis, married a 14-year-old girl, his cousin. Coppola’s film probes into the similar relationship between Elvis and Priscilla, offering an iconoclastic depiction of the singer and a critical understanding of Priscilla’s subjectivity. Anchored by a marvelous performance from Cailee Spaeny (excellent on FX’s Devs), it explores how a teenager’s dreams came true, how she became her idol’s best girl, and how some perspective on the situation reveals their courtship as a case of prolonged grooming followed by toxic possessiveness. Coppola’s film is a refreshing, feminist assessment of Elvis after so many years of exultant, somewhat rose-colored accounts of The King and his legacy. Committed to telling Priscilla’s story, Coppola immerses the viewer in the headspace of a girl whom Elvis exploits and suffocates with his celebrity and power, his threats followed by apologies, and his manipulation and control. As a result, Priscilla may leave some viewers at a remove, unable to connect with its protagonist’s mostly passive, subordinate role, but therein is the film’s brilliance as an almost diagnostic portrait of a troubling relationship.

Coppola’s film supplies an alternative to Baz Luhrmann’s kaleidoscopic Elvis (2022), both in terms of perspective and execution. Whereas Luhrmann deployed stylistic bombast to glorify the singer and perpetuate the notion that Colonel Tom Parker preyed upon him, Coppola offers a subtle, restrained appraisal of the relationship between Elvis and Priscilla, characterizing the star’s behavior as predatory. The approach proves surprising, considering that the real-life Priscilla Presley serves as executive producer, and the screen story is based on her 1985 book, Elvis and Me, co-authored by Sandra Harmon. Often, when someone is involved in their own biopic or that of a close relation, the less-than-honest outcome aggrandizes rather than evaluates its subject. Then again, her book emerged in an era of celebrity tell-alls, such as Mommie Dearest (1978), when the juiciest scandals sold millions of books. To be sure, the real Priscilla doesn’t seem to have put any limits on Coppola, who wrote the adapted screenplay into a sharp observation of masculine predation from Priscilla’s perspective, with endless lines of dialogue that provide textbook examples of Elvis’ rather calculating, wolfish behavior.

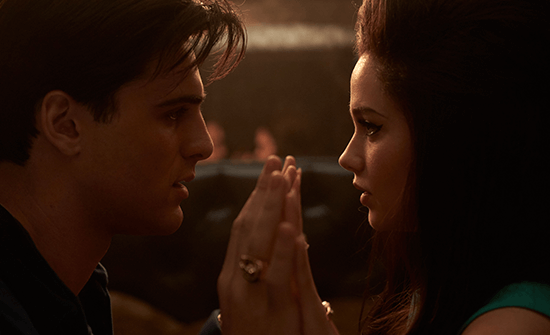

The story opens in 1959, on the US air base in West Germany, where Elvis (Jacob Elordi, terrific) was stationed. Spied at a nearby diner by music booker Terry West (Luke Humphrey), Priscilla looks appropriately girlish and diminutive, a quality emphasized by Spaeny’s short stature and nymphish appearance. So it’s strange when Terry asks if she’d like to meet Elvis at his place. Of course she would, being a 15-year-old who, like many girls her age, has only dreamed about meeting the most famous rock ‘n’ roller on the planet. After working to convince Priscilla’s concerned parents of Elvis’ “good intentions,” Terry wrangles Priscilla under the pretense of introducing the lonely Elvis to a fellow American overseas—even though friends and family surround him at his digs in Germany, seemingly away from military oversight. After just one encounter, the rest of Priscilla’s life seems pointless. How could she return to junior high, taking banal lessons in French and learning about the four basic food groups after that? Coppola’s screenplay and Spaeny’s quiet screen presence capture how Priscilla is a girl seduced by a fantasy-come-true scenario that, with time and from the filmmaker’s vantage point, looks disturbingly problematic.

Priscilla also builds a veritable case study in grooming behavior and pathological toxicity, as though Elvis attended Frank T.J. Mackey’s “Seduce and Destroy” seminar from Magnolia (1999) and absorbed every word. Taking advantage of Priscilla’s celebrity crush, Elvis suggests they “go somewhere quiet” if only so he can talk about himself. He earns her sympathy by creating a tragedy regarding his dead mother and claiming he’s homesick in Germany. If he seems sensitive and insecure, at times wishing he could act like Marlon Brando and James Dean, he’s also a predator sniffing after a teen he wants to preserve in a doll-like fashion. When his military service ends, and he must leave her behind, Elvis tells Priscilla, “Promise me you’ll stay the way you are now.” And he ensures as much by eventually flying the then-16-year-old to Memphis, where one of the other young women among his groupies observes of Priscilla, “Wow, she’s young. She’s like a little girl.” Indeed, Elvis calls her “little one” and later asks, “Are you gonna be a good girl?” He then proceeds to do what he can to preserve Priscilla’s childish innocence, buying her a puppy and enrolling her in a good Catholic school (where a nun tells him, “The Lord is with you… and your hips.”).

Priscilla also builds a veritable case study in grooming behavior and pathological toxicity, as though Elvis attended Frank T.J. Mackey’s “Seduce and Destroy” seminar from Magnolia (1999) and absorbed every word. Taking advantage of Priscilla’s celebrity crush, Elvis suggests they “go somewhere quiet” if only so he can talk about himself. He earns her sympathy by creating a tragedy regarding his dead mother and claiming he’s homesick in Germany. If he seems sensitive and insecure, at times wishing he could act like Marlon Brando and James Dean, he’s also a predator sniffing after a teen he wants to preserve in a doll-like fashion. When his military service ends, and he must leave her behind, Elvis tells Priscilla, “Promise me you’ll stay the way you are now.” And he ensures as much by eventually flying the then-16-year-old to Memphis, where one of the other young women among his groupies observes of Priscilla, “Wow, she’s young. She’s like a little girl.” Indeed, Elvis calls her “little one” and later asks, “Are you gonna be a good girl?” He then proceeds to do what he can to preserve Priscilla’s childish innocence, buying her a puppy and enrolling her in a good Catholic school (where a nun tells him, “The Lord is with you… and your hips.”).

Elvis’ controlling behavior resembles another cinematic obsessive when he takes a page out of James Stewart’s playbook in Vertigo (1958), building himself an object of affection. He buys Priscilla clothes he likes, instructing her how to dress in solids, not patterns, which color to dye her hair, and how to apply her eye makeup. Numbing her resolve by sharing his pill-popping habit—uppers in the morning, downers at night—she concedes. But this behavior isn’t a sex thing, at least, not at first (not that it needs to be to cross a sexual boundary to enter creepy territory). In fact, he seemingly preserves her virginity until their wedding night, calling sex “very sacred.” His behavior is about control, which feeds his ego. It’s always about his needs, and Coppola’s script characterizes him with demands such as “I need someone who’s going to…” and threats such as “There are plenty of other women who…” When she asks to get a job while he’s away in Hollywood shooting a movie, he warns, “It’s either me or a career, baby.” He insists she needs to lighten up, show interest in his interests, and understand that when he smacks her too hard with a pillow or throws a chair at her head that it was “an accident” or he “didn’t mean it.” Encouraged by his fans, the tabloids, and his gaggle of yes-men, Elvis expects everyone around him to concede.

Coppola expresses all of this shady behavior in Priscilla with an equally shady light. Cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd, who also shot Coppola’s The Beguiled (2017) and On the Rocks (2020), creates an aesthetic far more naturalistic than Luhrmann’s candy-colored production, preferring to render kitchens, bedrooms, and casinos in a muted, shadowy palette of brown soup and pastels. The authentic production design by Tamara Deverell and costumes by Stacey Battat draw from reality wherever possible. Still, Coppola’s presentation, no matter how beautiful at times, serves her theme like rotten fruit in a still-life painting. Similarly, when Elvis finally proposes, the music by Phoenix and Sons of Raphael draws from “Gassenhauer” from Carl Orff’s Schulwerk—the same music was used to serenade doomed or criminal lovers in Badlands (1973) and True Romance (1993). With anachronistic songs on the soundtrack, a tactic deployed in another of Coppola’s period dramas, Marie Antoinette (2006), the film resists embracing Elvis’ music or romanticizing him through his artistic output, thereby maintaining its critical perspective.

Spaeny’s performance is a tour de force and earned her the Volpi Cup for Best Actress at the Venice Film Festival. For much of the film, her presence is reserved and unquestioning, simply a teenage girl attempting to maintain her seemingly lucky situation. Elordi has the showier role with more dialogue, often acting out in ways Spaeny must tiptoe around. Elvis makes demands of Priscilla’s behavior, shows a blatant disinterest in taking a family portrait, and becomes violent. By design, Coppola gives little dimension to Priscilla’s inner life early on because of her youth and inexperience—she’s wrapped up in a reverie every other girl on the planet would kill for, and she accepts Elvis’ treatment of her as normal at first. “You have everything a woman could want,” Elvis tells her, defending his bad behavior and censuring her dissatisfaction. Though he claims to love her, their relationship is contingent on her willingness to bend to his every order and desire, and not question his infidelities with Ann-Margret and Nancy Sinatra, featured in tabloid gossip. “I need a woman who understands things like this might happen. Are you her or not?” he threatens.

Spaeny’s performance is a tour de force and earned her the Volpi Cup for Best Actress at the Venice Film Festival. For much of the film, her presence is reserved and unquestioning, simply a teenage girl attempting to maintain her seemingly lucky situation. Elordi has the showier role with more dialogue, often acting out in ways Spaeny must tiptoe around. Elvis makes demands of Priscilla’s behavior, shows a blatant disinterest in taking a family portrait, and becomes violent. By design, Coppola gives little dimension to Priscilla’s inner life early on because of her youth and inexperience—she’s wrapped up in a reverie every other girl on the planet would kill for, and she accepts Elvis’ treatment of her as normal at first. “You have everything a woman could want,” Elvis tells her, defending his bad behavior and censuring her dissatisfaction. Though he claims to love her, their relationship is contingent on her willingness to bend to his every order and desire, and not question his infidelities with Ann-Margret and Nancy Sinatra, featured in tabloid gossip. “I need a woman who understands things like this might happen. Are you her or not?” he threatens.

As the betrayals grow in number, Priscilla is gradually released from Elvis’ gravitational pull. Spaeny imbues the character with increasing concern and independence in the final third, leading to the moment when Priscilla leaves Graceland in 1972. Coppola sets the final moments of Priscilla abandoning her so-called dream life to Dolly Parton’s aching “I Will Always Love You.” Supposedly, it’s the song Elvis sang to Priscilla after they acquired a divorce, but here, it plays as less mournful for the marriage than in line with Parton’s independent streak (she refused to allow Elvis to cover her song). Besides being a contrast to Loretta Lynn’s “Stand by Your Man,” Parton’s lyrics—“Goodbye, please don’t cry, ’cause we both know that I’m not what you need”—resonate in this moment. They’re the words of a woman who finally feels empowered to act for herself, using references to his needs that the egomaniacal Elvis could understand.

Another of Coppola’s many films about women inhabiting a world intent on using and alienating them rather than empathizing with them, Priscilla is easily the filmmaker’s best work to date. It sees Priscilla’s relationship with Elvis for what it was, unmoored from the celebrity phenomenon and vitally uncommitted to preserving the legend. If Coppola once more seeks to humanize the people behind the myths, her agenda is far more successful here than in Marie Antoinette—where the director had a questionable perspective on history and her titular character. Humanized by Spaeny’s arresting screen presence and thoughtful performance, and how she conveys Priscilla’s inner growth throughout, the film compares to Pablo Larraín’s biopics Jackie (2016) and Spencer (2021)—recent cinematic stories that endeavor to recontextualize overlooked and misunderstood famous women. This is exceptional filmmaking, from the performances to the conceptual realization, and among the best films of 2023.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review