Ondine

By Brian Eggert |

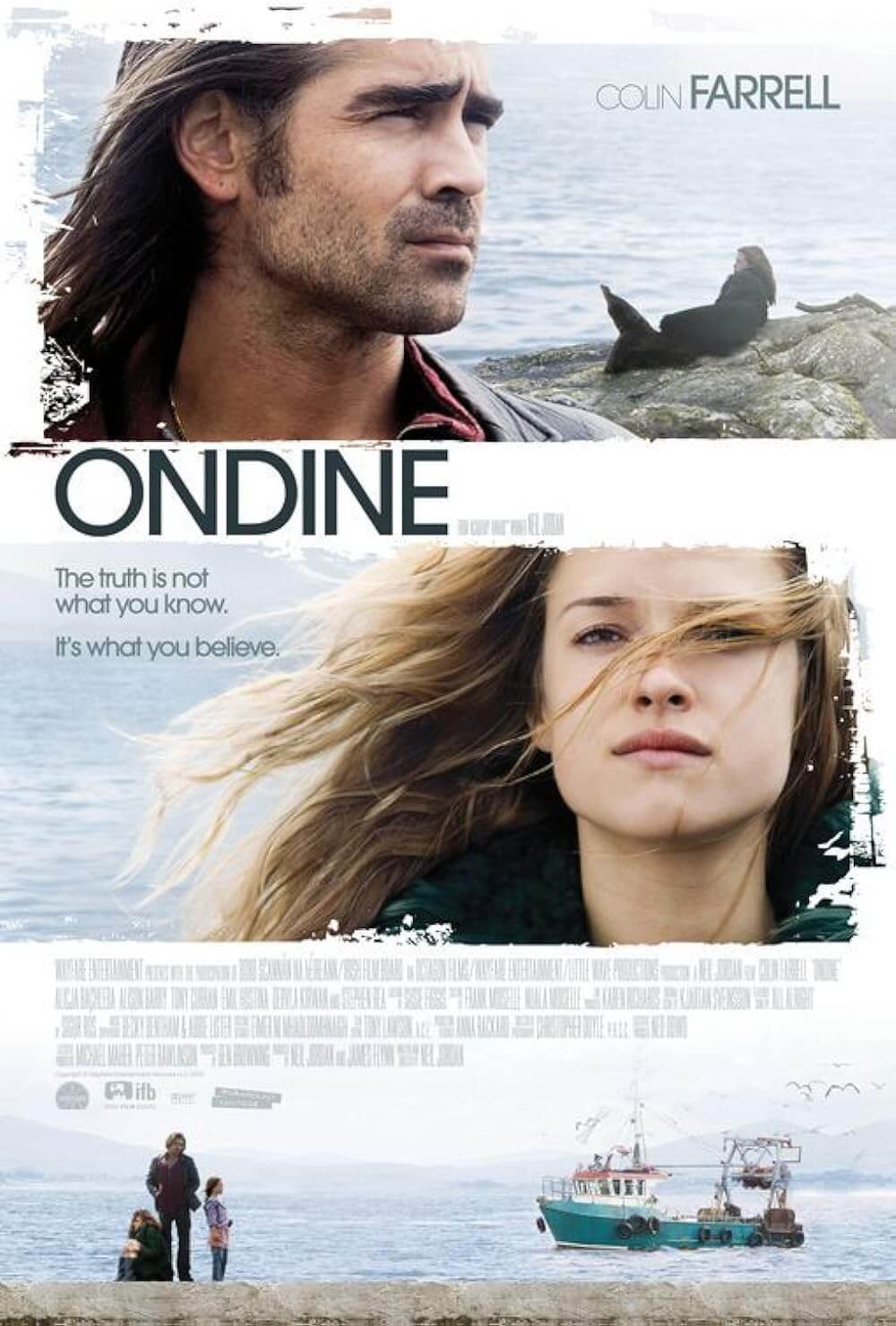

Irish writer-director Neil Jordan scripted his latest picture, Ondine, for star Colin Farrell, the former Irish bad-boy who has since reformed his wild ways to become an increasingly respectful actor. Farrell displays impressive vulnerability in the film, a characteristic that has served him well in his post-tabloid career, despite his rough-around-the-edges persona. Here the actor’s skills maintain a fine little fairy tale about extraordinary things happening to very normal people. The unique combination of hopeful fantasy and gritty, overcast realism marry in a heartwarming drama, not for children, but rather for the child in every adult.

Farrell plays Syracuse, a loner fisherman who’s two years sober and struggling with his bumpy past. Mocking locals call him “Circus” in reference to his former drunkard, clownish ways—a name he cannot live down. One day he catches a young woman (Alicja Bachleda) in his nets and revives her. She tells Syracuse her name is Ondine, and that she doesn’t want to be seen by anyone but him. He takes her in, allows her to sleep in his home and tag along on fishing runs, and concedes to her demands that she not be seen. They spend several days together, and he finds that, strangely, when she sings on his boat, his luck seems to change, as only with her song are his fish nets packed and his lobster cages full.

On visits with his daughter, Annie (Alison Barry), who lives with his ex-wife, Syracuse speaks of Ondine as though she was something out of a storybook. The bright and quick-witted Annie immediately believes that Ondine is a selkie, a sort of mermaid from European lore. As the legend goes, selkies often come to shore to fall in love with a “landsman”—and wouldn’t her father make a nice husband for this mythical creature? Meanwhile, Syracuse doubts that she exists at all. Perhaps he’s imagining her. He confesses his doubts to his priest (Stephen Rea), who takes the place of Alcoholics Anonymous in a town where sobriety is rare. But, to be sure, Ondine is quite real, as are her affections. As to whether she’s a selkie or not, who can say?

The film works out in a way that will deter otherwise obvious comparisons to similar but more lighthearted fare like Splash. Indeed, this is hardly a comic romp filled with flippers and magic; the result is decidedly more substantial. And yet, the gloomy cinematography by Christopher Doyle (Dumplings, Rabbit-Proof Fence) captures the windswept, unforgiving atmosphere of Ireland without losing a sense of wonder about the enchanted plot. Moreover, Jordan has a pleasant way of walking the line between the story of a struggling alcoholic and an extraordinary, mythical sea being, with respect to both plotlines’ integrity.

Moving from drivel like Daredevil and S.W.A.T. to more esteemed work such as Cassandra’s Dream and In Bruges, Farrell’s career has been a mixed bag, filled with an occasional, yet increasing, number of superb films. He’s worked with some of the greatest living filmmakers, including Terry Gilliam (The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus) and Terrence Malick (The New World). And his work here is further confirmation that as Farrell puts distance between himself and his former wild days in Hollywood, he grows closer to becoming an immense talent whose work should be sought out. Surely Ondine is one of those titles.

Supporting Farrell, Jordan’s direction is confident, with hints of realism in the gray skies of Ireland’s cynical backdrop and also faint suggestions of fantasy as Ondine emerges from the water, alluring and other-worldly. He’s an against-type filmmaker whose approach always supports the story, even while his recurrent themes emerge from under the surface. Sometimes this benefits him, as with The Crying Game or The Butcher Boy. In contrast, with his lesser scripts (such as The Good Thief, a lousy remake of Jean-Pierre Melville’s French classic Bob le flambeur), his presence behind the camera disappears altogether. He’s made some duds in the last few years, most recently The Brave One, but he’s revalidated himself once more by returning to a thankfully small and welcomed Irish fairy tale.

With sentiments rooted in the power of belief and the need for something fantastic in one’s life, Ondine is a surprisingly heartfelt, mature story about tangible characters entrenched in marvelous circumstances. Never delving too deep into impossible territory, Jordan keeps the emotions familiar and the fantastical elements negligible. This formula makes the selkie component of the story all the more affecting, as the film leaves so much to our imaginations, hoping, just as Syracuse does, that any piece of this fantasy (be it the reality of the selkie or the love of an attractive woman) might be real for our protagonist. What a joy it is when at least one of these possibilities turns out to be true.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review