Reader's Choice

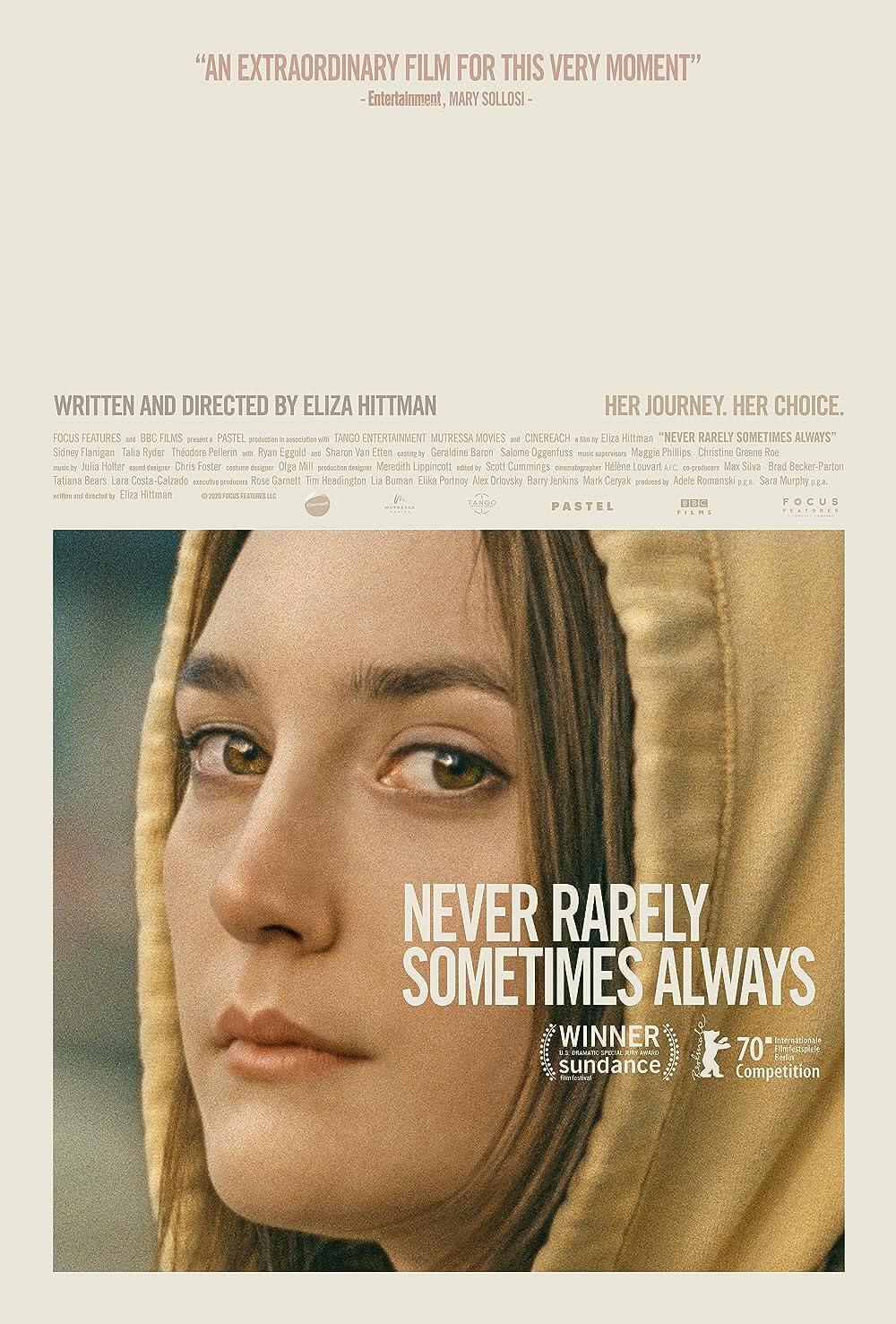

Never Rarely Sometimes Always

By Brian Eggert |

Eliza Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always avoids the type of political rhetoric and overt dramaturgy that could have made it disingenuous, thus ineffectual, or more of a statement than a feeling experience. Although it centers on an inward 17-year-old, Autumn (Sidney Flanigan), who travels from Pennsylvania to New York to receive an abortion, the film balances its social consciousness with a tender and human story. Without judgment, only detailed observation, Hittman immerses the viewer in Autumn’s experience as she seeks to terminate her unintended pregnancy. However, it could hardly be called a film whose subject is abortion or reproductive rights. So much of its runtime involves seeing the world from Autumn’s point of view—she visits a women’s clinic, rides on buses and subways, and wanders New York alongside her more world-wary cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder). The film immerses us in these distinct perspectives, and the commentary comes naturally. Hittman’s fidelity to that ambition rarely wavers, resulting in a film that feels authentic, even vital for our time.

In a sense, Hittman has made a coming-of-age film about a teenager who resolves to take charge of her own body and future. After Autumn returns home from a crisis pregnancy center where she discovers that she’s several weeks along, she has already made up her mind to have an abortion. The next thing she does is pierce her nose in an act of self-possession. Since she comes from a small, drab town in a state that demands parental consent, she and Skylar spring for a New York trip. Hittman shows Autumn and Skylar’s interactions with several men, from their grocery store boss whose unwanted advances come through a narrow passage to a public masturbator. Men keep asserting themselves into Autumn and Skylar’s lives, including a fellow bus passenger, Jasper (Théodore Pellerin), who touches Skylar’s arm to make chit-chat before insisting on getting her number for a meet-up in New York. It’s a long trip, and the cousins barely speak to one another about these encounters or what will happen when they arrive. But their brief exchange about Jasper’s repeated texts reveals that they must navigate a barrage of intrusive come-ons as part of everyday life.

For the first half of the film, Hittman adopts an effective, albeit affected docudrama style that conforms to modern formal notions of realism—a stripped-down aesthetic that makes the viewer feel present and in the moment with Autumn. Julia Holter’s score amounts to recessive mood tones. Earlier scenes have a muted, grayed out color palette; the skies look perpetually overcast with visible grain activating everything in the frame. Cinematographer Hélène Louvart shoots on 16mm stock in mostly handheld camerawork that feels like guerilla filmmaking at times, especially on New York streets, where the occasional passer-by glances at the camera. The city scenes feel more alive; based on color alone, Hittman seems to argue for the city over small-town life with its enlivened visuals. Through it all, the frame almost always occupies Autumn’s perspective, aside from the odd moment or two from Jasper’s view as he ogles Skylar—a curious inclusion, to be sure.

The film’s restrained style mirrors Autumn’s quiet, introverted presence, enhanced through the stark contrast of the devastating scene when the story’s emotions reach their height. Autumn meets with her Planned Parenthood counselor and answers questions about her pregnancy and sexual history. She must provide one of the multiple-choice responses supplied by the title, and her responses, or lack thereof, are both telling and utterly crushing. This sequence takes us back to the opening scenes at a high school talent show, where clean-cut teens perform in a series of back-to-the-sixties-inspired songs that typify their carefree worldview. Then Autumn appears in glittery eye makeup, performing a decidedly modern cover of The Exciters’ pop tune “He’s Got the Power” from 1963. The painful truth of the lyrics—“He makes me do things I don’t want to do/He makes me say things I don’t want to say/He’s got the power, the power of love over me”—won’t become clear until Autumn’s interview with her counselor. We also think back to her treatment by her mother’s husband (Ryan Eggold), whose use of the word “slut” with the family dog seems pointed, and we wonder if he might be Autumn’s abusive partner. But those familiar with Hittman’s debut It Felt Like Love (2013) or second film Beach Rats (2017) will know she prefers to keep narrative exposition to a minimum, leaving associations such as this to the viewer.

The film’s restrained style mirrors Autumn’s quiet, introverted presence, enhanced through the stark contrast of the devastating scene when the story’s emotions reach their height. Autumn meets with her Planned Parenthood counselor and answers questions about her pregnancy and sexual history. She must provide one of the multiple-choice responses supplied by the title, and her responses, or lack thereof, are both telling and utterly crushing. This sequence takes us back to the opening scenes at a high school talent show, where clean-cut teens perform in a series of back-to-the-sixties-inspired songs that typify their carefree worldview. Then Autumn appears in glittery eye makeup, performing a decidedly modern cover of The Exciters’ pop tune “He’s Got the Power” from 1963. The painful truth of the lyrics—“He makes me do things I don’t want to do/He makes me say things I don’t want to say/He’s got the power, the power of love over me”—won’t become clear until Autumn’s interview with her counselor. We also think back to her treatment by her mother’s husband (Ryan Eggold), whose use of the word “slut” with the family dog seems pointed, and we wonder if he might be Autumn’s abusive partner. But those familiar with Hittman’s debut It Felt Like Love (2013) or second film Beach Rats (2017) will know she prefers to keep narrative exposition to a minimum, leaving associations such as this to the viewer.

Of course, there’s certainly potential for Hittman to stand on a soapbox and turn her film into a polemic. For the moment, abortion remains legal in the United States; however, the current presidential administration exploits every opportunity, including the COVID-19 pandemic, to limit safe and affordable means for women to access legal abortions. There’s an active push to eliminate the rights women have over their bodies, and Hittman’s film shows the consequences of this. Watch Autumn’s interactions with the initial crisis pregnancy center whose idea of a pregnancy test is an over-the-counter urine solution, not a blood test. Once they confirm the results, a counselor, who mentions that she’s also a mother, asks, “Are you abortion-minded?” When Autumn confirms that she is, she’s shown a harsh anti-abortion video. Hittman reveals that, unlike Planned Parenthood, pregnancy resource centers often receive funding from Christian groups and other anti-abortion organizations that have an agenda outside of helping women receive proper care. Their dubious professionalism is apparent when they send Autumn home with a pathetic gift bag full of informational brochures.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always marks the incredible debut of Flanigan, a young musician in her first onscreen acting role. It’s a debut that recalls Elsie Fisher in Eighth Grade or Thomasin McKenzie in Leave No Trace, both from 2018, in that she’s capable of creating an inner character out of the minimal dialogue. Ryder, too, is excellent. Hittman’s film allows both performers to confront the dangers young women face and the fortitude they must have. It’s a portrait whose remarks about predatory men and abortion in America linger on the margins, showing how crisis pregnancy centers have ulterior motives; how Planned Parenthoods must have metal detectors and bag checks for fear of extremists; how frequently women’s bodies are subject to the whims of men; and how young women prevented from access to abortions will resort to great, even dangerous lengths to obtain one. It’s even more impressive that Hittman does all this with a PG rating. Despite the heavy subject matter, she makes the film accessible and gives an immersive look at the perspective of young women today.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review