Megalopolis

By Brian Eggert |

“We’re in need of a great debate about the future.”

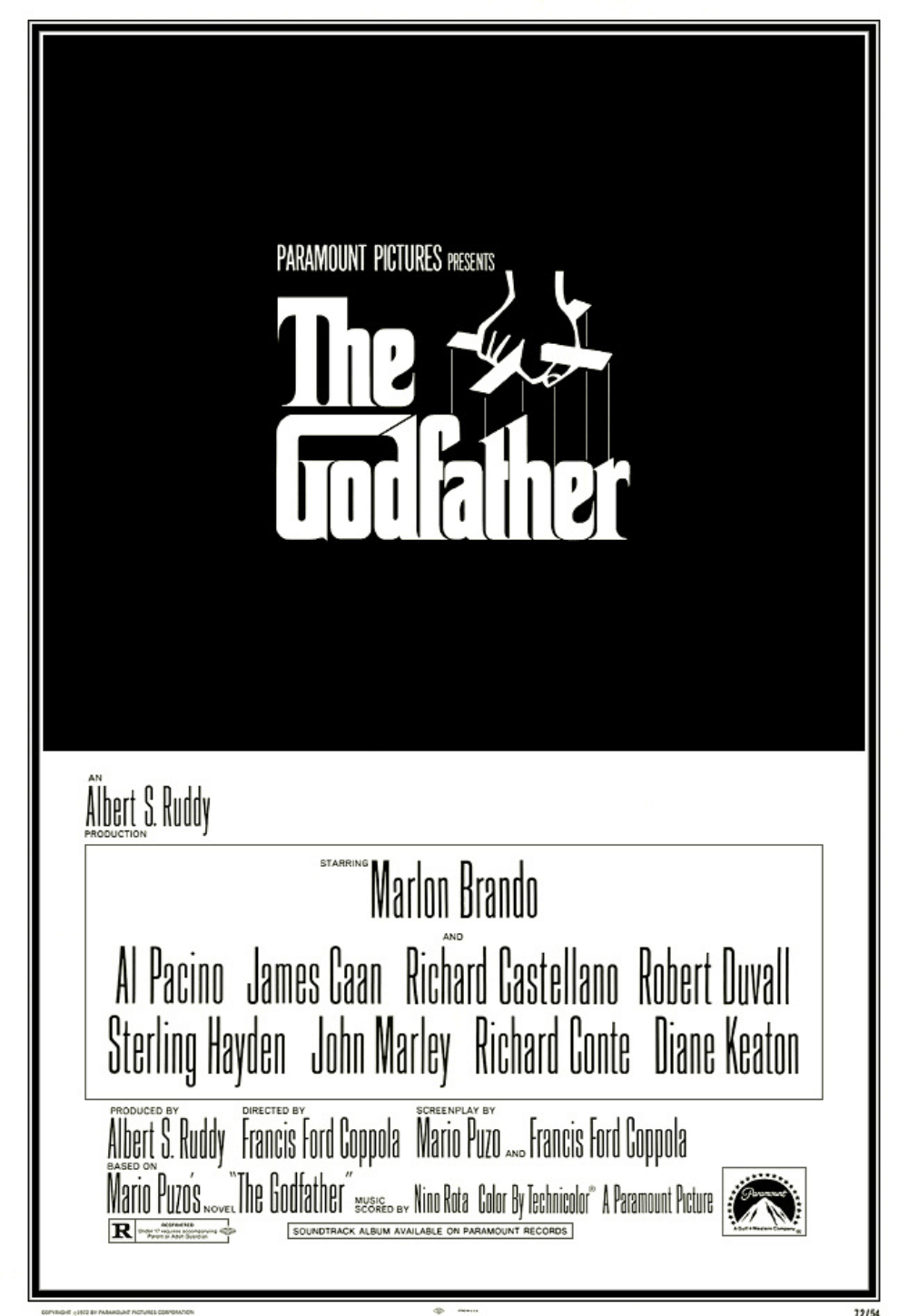

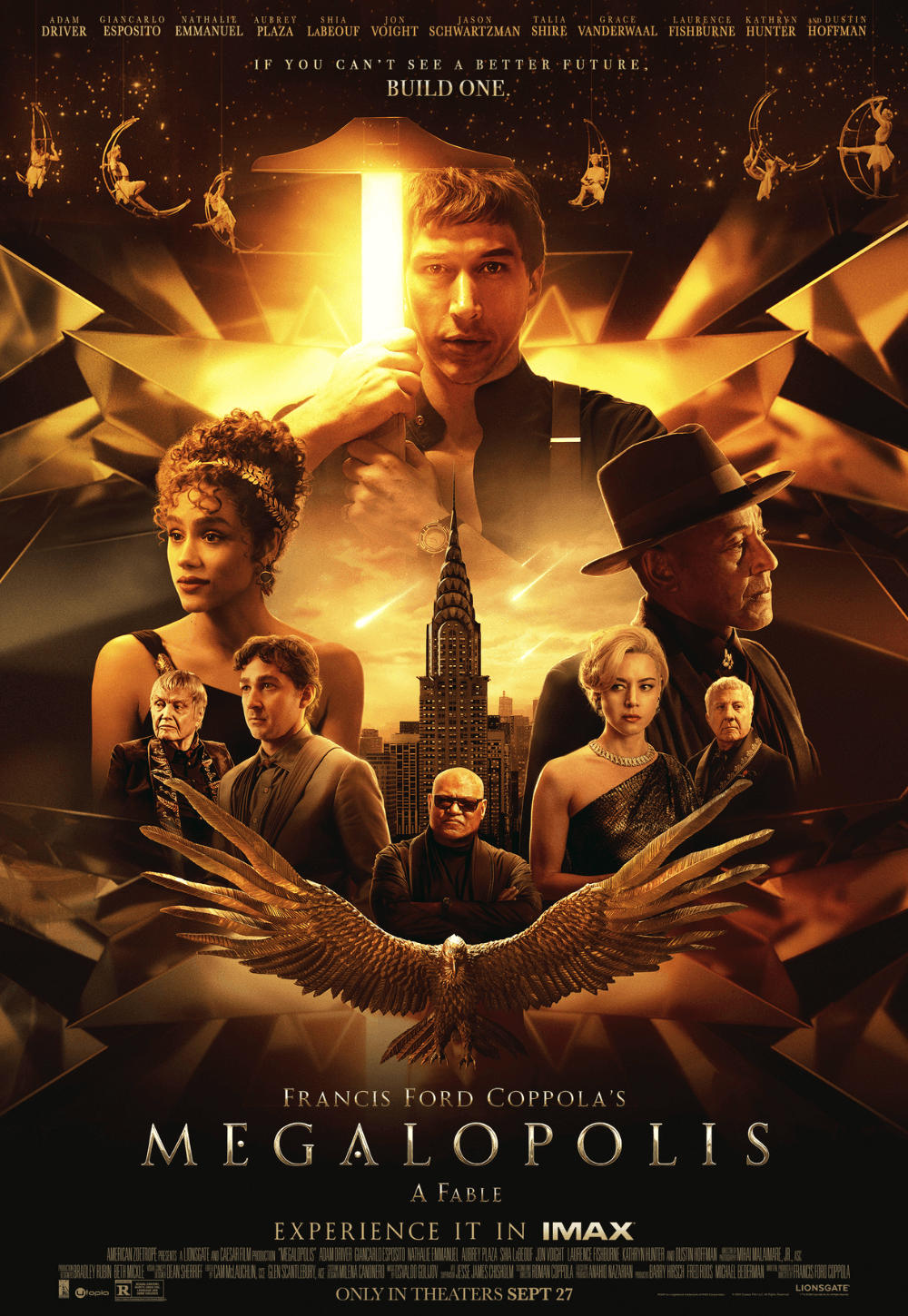

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis is a beautiful disaster—a visionary calamity of unconventional filmmaking and artistic imperatives. With notes of science fiction, ancient Roman history, and existential dread about America’s possible future, this anti-commercial epic questions whether humanity can be saved from itself. Overstuffed with Coppola’s hopes and sentiments about what may come, his long-awaited production spews out ideas and formal impulses with less interest in following a familiar narrative structure or building fleshed-out characters than putting it all out there. The 85-year-old filmmaker is responsible for some of cinema’s greatest masterpieces, from The Godfather trilogy to Apocalypse Now (1979), and he has a rich history of going for broke. His latest and possibly last picture is a rambling meditation that might be the ravings of a legend or the earnest outpourings of an artist who hopes his message cuts through the world’s noise. Coppola’s distinct vision doesn’t necessarily translate to a satisfying or cohesive picture, but it’s difficult to fault him for putting so many resources into what is an imposing personal and artistic statement. Even while Coppola struggles to control his messy exhibition, he yearns to create a work of art that stops time and allows for consideration outside of this moment, leaving him to impart lessons on living a meaningful life and building an optimistic future.

Promotional material calls Megalopolis “A Fable” and, true to form, the film conveys its lesson in overt dialogue, albeit with storytelling that distributor Lionsgate has struggled to market. In this impossible-to-categorize film, Adam Driver plays Cesar Catilina, an eccentric genius who presides over the Design Authority office in New Rome, ostensibly New York. Its citizens dress in retrofuturist garb for a sci-fi retelling of the Catiline Conspiracy to overthrow the Roman Republic in 63 BCE. Caesar plans to erect an interconnected utopia, bringing the entire urban landscape together with an advanced technology called Megalon—a glowing substance that, in a lesser film, may have been a MacGuffin. Instead, political machinations, scandals, a corporate takeover, and debates about the fate of New Rome ensue. All the while, Coppola grapples with intermittent themes such as power, philosophy, family, legacy, and artistic expression, occasionally echoing present-day questions about America’s fate in the 2024 election. Directing a cast that includes Aubrey Plaza, Giancarlo Esposito, Shia LaBeouf, Laurence Fishburne, and Jon Voight, among many other familiar faces, Coppola allows himself to get lost in kaleidoscopic sequences, triptych split-screen montages, and a loose narrative framework, telling a story that ends on a note of aspirational prescience.

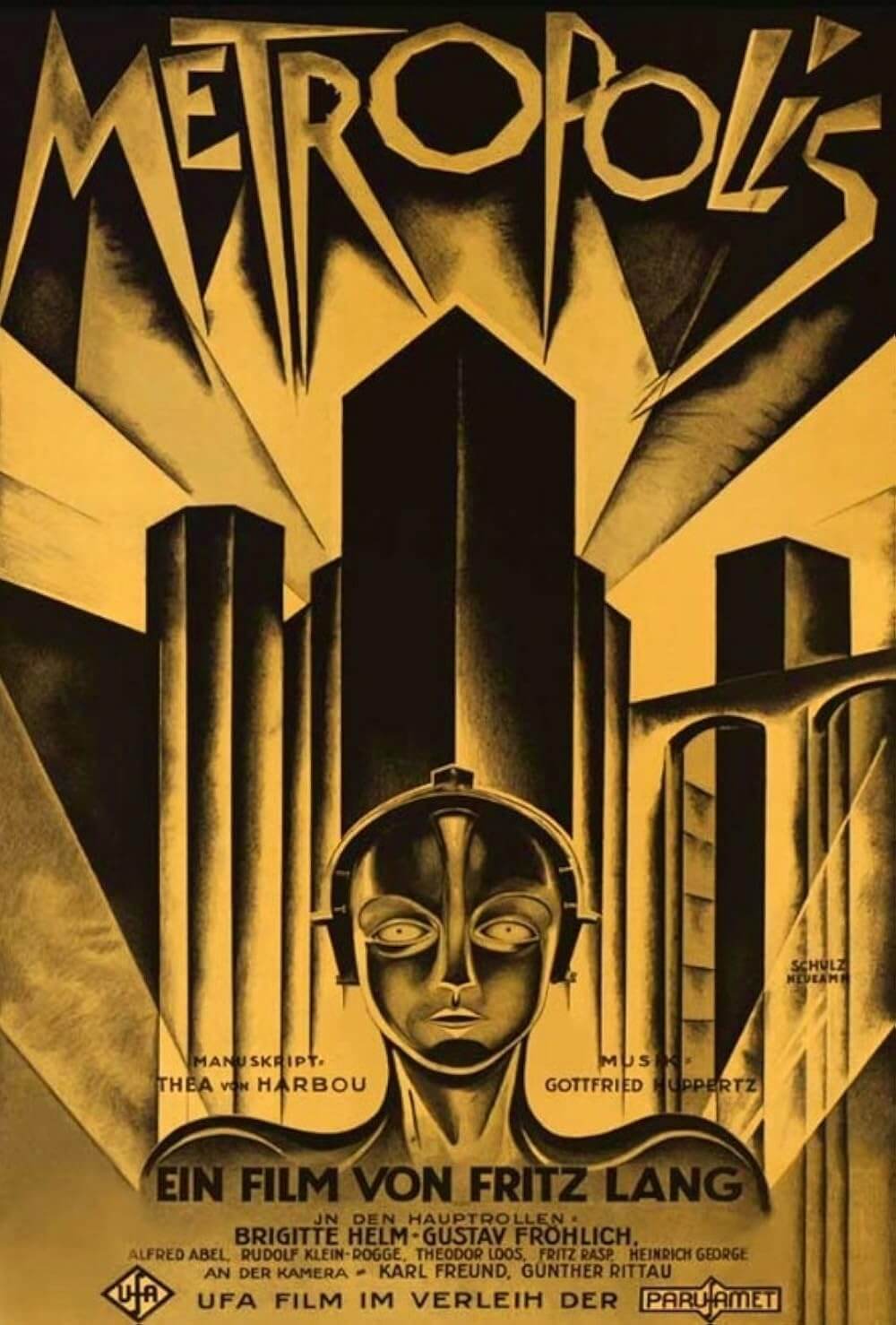

In Sam Wasson’s Coppola biography from last year, The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story, the author details how Megalopolis represents a decades-long work in progress, which the director romanticizes as the apex of his artistic ambition and ideals. Coppola has been developing Megalopolis for almost half a century. In the late 1970s, while he was making Apocalypse Now, he first conceived the ambitious project set in a futuristic New York City. Drawing parallels between ancient Rome and America, the proposed film would address grandiose themes about an indulgent and complacent society, vying political powers, hedonism among the super-rich, and the construction of a utopia to resolve social disenchantment. In the wake of the turbulent political corruption and scandals during Nixon’s presidency, along with a general loss of faith in American institutions, Coppola saw America on the downswing, echoing the Pax Romana’s end with the similar erosion of the Pax Americana. He wanted to explore these concepts in a manner rivaling Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), using a production of vast formal innovation that would allow him to experiment with and redefine the limits of cinema through his production company, American Zoetrope. After his incredible run of films in the 1970s—The Godfather (1972), The Conversation (1974), The Godfather Part II (1974), and Apocalypse Now—Coppola believed he could single-handedly reshape cinema with his American Zoetrope projects. And in the early ’80s, the director began drafting ideas and making plans to mount his ambitious production. However, the box-office failure of One from the Heart (1982), his soundstage musical designed to show the technical prowess of American Zoetrope’s new production facilities, left Coppola in financial ruin.

After One from the Heart, commentators lumped Coppola in the same group as William Friedkin and Michael Cimino, whose indulgences with Sorcerer (1977) and Heaven’s Gate (1980), respectively, led to highly publicized financial disasters (though, some have since reassessed these so-called failures as masterpieces). Hollywood responded by curbing the artistic latitudes of auteurs, exercising more studio control, and cracking down on budgetary freedoms. In the aftermath, Coppola launched into a period of work-for-hire jobs and commercial safety nets that lasted throughout the subsequent two decades, making Megalopolis seem like a pipe dream. Although he directed a few gems in this period—Rumble Fish (1983), Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988), Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), and The Rainmaker (1997)—it wasn’t until the late 1990s, after his finances began to stabilize, that he revisited the project. More rewrites, pre-production planning, and special effects tests followed. Coppola often talked about the project in interviews; it was always going to be his next film. The false starts and delays, including a major one due to the 9/11 attacks, continue to derail the project, imbuing Megalopolis with an almost mythical status. Another filmmaker might have moved on, deciding that it wasn’t meant to be, just as Stanley Kubrick had done with his Napoleon biopic after years of extensive research and planning. However, Coppola kept his passion for Megalopolis alive, encouraged by the promise of CGI to help realize his expansive vision. Then, in 2021, the director sold his lucrative wineries and resolved to self-finance his dream project with $120 million of his own money.

After One from the Heart, commentators lumped Coppola in the same group as William Friedkin and Michael Cimino, whose indulgences with Sorcerer (1977) and Heaven’s Gate (1980), respectively, led to highly publicized financial disasters (though, some have since reassessed these so-called failures as masterpieces). Hollywood responded by curbing the artistic latitudes of auteurs, exercising more studio control, and cracking down on budgetary freedoms. In the aftermath, Coppola launched into a period of work-for-hire jobs and commercial safety nets that lasted throughout the subsequent two decades, making Megalopolis seem like a pipe dream. Although he directed a few gems in this period—Rumble Fish (1983), Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988), Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), and The Rainmaker (1997)—it wasn’t until the late 1990s, after his finances began to stabilize, that he revisited the project. More rewrites, pre-production planning, and special effects tests followed. Coppola often talked about the project in interviews; it was always going to be his next film. The false starts and delays, including a major one due to the 9/11 attacks, continue to derail the project, imbuing Megalopolis with an almost mythical status. Another filmmaker might have moved on, deciding that it wasn’t meant to be, just as Stanley Kubrick had done with his Napoleon biopic after years of extensive research and planning. However, Coppola kept his passion for Megalopolis alive, encouraged by the promise of CGI to help realize his expansive vision. Then, in 2021, the director sold his lucrative wineries and resolved to self-finance his dream project with $120 million of his own money.

All of this is to illustrate that Megalopolis comes with a certain amount of expectation and anticipation for cinephiles and critics who are finally seeing it. Does the result reflect four decades of dreaming and planning? Will this be the culmination of his life’s work as an auteur? Does Coppola reach the heights of his 1970s output, or does it align better with his more recent and uneven experimental work in the twenty-first century, such as Youth Without Youth (2007) and Twixt (2011)? Certainly, much of the buildup has been deflated by the mixed reception after its Cannes Film Festival debut this year. Watching the result, whatever lofty hopes I might have had for an unqualified masterpiece hardly feel met. However, one must also acknowledge the passion with which Megalopolis was made, along with its sentiments about the value of human creativity, and that if people from opposing ideologies just worked together, the future might not look so grim. Then again, I must acknowledge that, had any other filmmaker been responsible for this apart from Coppola, its faults might not have been so easily overlooked and rationalized.

What’s curious about Coppola finally getting his long-gestating project made is that much of the screenplay reflects urgent contemporary concerns, namely its parallel between an attempted coup of the Roman Republic with America being on the cusp of electing an “emperor” this November. It feels less like something Coppola has been working on for decades than an urgent and immediate reaction to contemporary anxieties, which is perhaps a commentary on the circularity of political movements over time. And time is an essential component of his picture. Coppola frames his complicated and deeply flawed protagonist, Caesar, as seeing beyond the immediate and petty struggles of political and social groups in his efforts to improve the world for all. Caesar first appears atop a skyscraper, the digital clouds in the background moving at impossible speeds, until he calls out, “Time, stop!”—and it does. The film attributes this unique ability to artists of a particular caliber, which, of course, Coppola identifies with. It’s this ability that, later in the story, interests and attracts Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel), daughter of New Rome’s Mayor Cicero (Esposito). Once they’re together, Julia becomes Caesar’s muse, inspiring him to manifest his vision of “Megalopolis” into a reality. While he yearns to build a utopia, Caesar prepares by detonating rundown buildings otherwise inhabited by the lower class, leaving downtrodden masses homeless and angry so he can build something better. Caesar ignores that every utopia can be a dystopia, depending on one’s vantage point, liberating some and oppressing others.

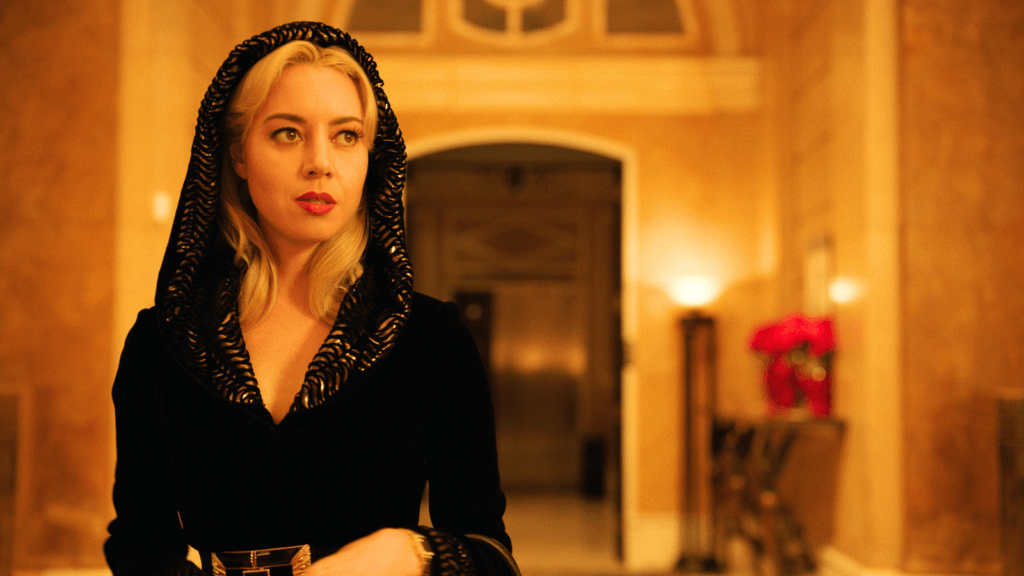

Meanwhile, an array of rich and powerful people vies for control over New Rome, and various political machinations stall Caesar’s plans. The opportunistic journalist, Wow Platinum (Plaza), takes her rejection by Caesar hard and resolves to marry his uncle, Crassus (Voight), a salacious banker who enjoys his wealth and power. Wow’s ambition to establish the ultimate “power couple” eventually finds her pursuing her hedonist stepson, Clodio (LaBeouf). Resentful that he gets no respect from his father and cousin, the Trumpian Clodio goes on a rabble-rousing campaign to exploit and marshal the “unwanted and uneducated” and make a decidedly fascistic name for himself, complete with allusions to Nazism and January 6th. Amid the film’s jumble of subplots—a celebrity sex scandal, a music video interlude by a literally transparent pop star, an assassination attempt, and Caesar’s checkered past involving an alleged uxoricide—it’s easy to feel lost in the unfocused storytelling. However, Coppola attempts to center his ideas by frequently quoting Marcus Aurelius, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William Shakespeare to elevate and clarify his narrative with lofty purpose.

Meanwhile, an array of rich and powerful people vies for control over New Rome, and various political machinations stall Caesar’s plans. The opportunistic journalist, Wow Platinum (Plaza), takes her rejection by Caesar hard and resolves to marry his uncle, Crassus (Voight), a salacious banker who enjoys his wealth and power. Wow’s ambition to establish the ultimate “power couple” eventually finds her pursuing her hedonist stepson, Clodio (LaBeouf). Resentful that he gets no respect from his father and cousin, the Trumpian Clodio goes on a rabble-rousing campaign to exploit and marshal the “unwanted and uneducated” and make a decidedly fascistic name for himself, complete with allusions to Nazism and January 6th. Amid the film’s jumble of subplots—a celebrity sex scandal, a music video interlude by a literally transparent pop star, an assassination attempt, and Caesar’s checkered past involving an alleged uxoricide—it’s easy to feel lost in the unfocused storytelling. However, Coppola attempts to center his ideas by frequently quoting Marcus Aurelius, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William Shakespeare to elevate and clarify his narrative with lofty purpose.

Among the roster of talent populating Metropolis, only Plaza appears to relish every moment onscreen, having apparently realized that the proceedings would register as high camp, albeit half intentional, half unintentional. Plaza steals the show from Driver and her costars, many of whom offer confounding or uneven performances. Voight seems past it, apart from a memorable scene toward the climax. LaBeouf’s improvisational energy lends the desired unpredictable quality to his character, but his presence is also grating and uneasy. Marred by stories (some debunked) of behind-the-scenes misconduct from the director, Coppola’s reportedly chaotic production nonetheless instills a collaborative spirit among politically divergent creatives. He knowingly cast well-known Trump supporters and “canceled” actors into the mix, proving that people from different backgrounds could work together—a noble ambition, to be sure. Other performers such as Jason Schwartzman, Kathryn Hunter, James Remar, and Dustin Hoffman have little to do, and most sport silly Caesar cuts that look like anachronisms to the modern garb. One could have guessed that the director’s sister, Talia Shire, would have a juicy role as Caesar’s senile mother. And Driver, once again, demonstrates that he’s one of the most fascinating actors working today, from pantomiming a game of tug-o-war with Julia to performing the “To be, or not to be” monologue from Hamlet and somehow not turning the scene into a cliché.

Intermittently narrated by Laurence Fishburne, who plays Caesar’s assistant, Megalopolis unfolds in a manner that’s difficult to follow from moment to moment. During any scene, you might ask yourself, What the hell is going on? But when it’s over, the overarching themes linger, mainly because Coppola has flat-out stated them in his preachy dialogue. Aesthetically, he presents the film in an amalgamation of period pieces from yesteryear (Anthony Mann’s The Fall of the Roman Empire from 1964 came to mind) and the chintzier end of modern CGI-heavy science fiction (think 2004’s Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow). Fittingly, apart from the use of some modern songs, Osvaldo Golijov’s score sounds like a throwback to Hollywood’s mid-twentieth-century sword-and-sandal epics, and the transitional marble titles also harken to that aesthetic. Elsewhere, Coppola and cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr. create a visual palette that looks like no other Coppola film, given its digital sheen in over-lit golden hues and expressive camera angles. Regardless of these incongruities, the director manages some stunning imagery: chunks of a satellite falling from orbit in the night sky, a symbolic statue of Lady Justice collapsing, and shots of Driver and Emmanuelle courting atop a skyscraper are stunners.

Coppola’s unconventional touches extend to the limited theatrical presentation in IMAX. At one point, during a press conference scene in the film, the auditorium’s lights came up slightly, and a man stood facing the movie theater screen in front of a microphone. Audible sounds of confusion from moviegoers and press filled the theater. Was there some emergency the theater management had to announce? No. Rather, Caesar looks at the man—a live actor playing an off-screen reporter—and engages with him. Afterward, the lights went back down, and the actor returned to his seat. Apart from never seeing anything quite like that, the moment speaks to Coppola’s desire to reinvent the cinema for the future (though this didn’t do the trick, it was something to behold). The unparalleled experience of watching a $120 million experimental film on an IMAX screen, complete with a live component, may rank among the most memorable theatrical experiences of my life. Even as I write that, I should also acknowledge I shifted in my seat during some of the more meandering segments. My screening had several walk-outs and vocal audience reactions that ranged from amusement to bafflement, all of which were understandable given the narrative runniness.

Coppola’s unconventional touches extend to the limited theatrical presentation in IMAX. At one point, during a press conference scene in the film, the auditorium’s lights came up slightly, and a man stood facing the movie theater screen in front of a microphone. Audible sounds of confusion from moviegoers and press filled the theater. Was there some emergency the theater management had to announce? No. Rather, Caesar looks at the man—a live actor playing an off-screen reporter—and engages with him. Afterward, the lights went back down, and the actor returned to his seat. Apart from never seeing anything quite like that, the moment speaks to Coppola’s desire to reinvent the cinema for the future (though this didn’t do the trick, it was something to behold). The unparalleled experience of watching a $120 million experimental film on an IMAX screen, complete with a live component, may rank among the most memorable theatrical experiences of my life. Even as I write that, I should also acknowledge I shifted in my seat during some of the more meandering segments. My screening had several walk-outs and vocal audience reactions that ranged from amusement to bafflement, all of which were understandable given the narrative runniness.

And yet, Megalopolis has ideas and moments that I will never forget, even if I didn’t enjoy every second of its 138-minute runtime. Among the only genuinely moving aspects of Coppola’s film is the affection Caesar displays for Julia in how she inspires him; though, one questions whether his love runs deeper or just supplies him with a good feeling about himself. It’s telling that Coppola dedicated the picture to his late wife, Eleanor, who, in her written work, considers the degree to which she was just her husband’s wife or an artist in her own right. But here, Julia and her eventual child are shown to be the future, Caesar less so. This notion, along with countless other facets of Coppola’s unfettered expression, contributes to the overall fluidity of Megalopolis—a work of art constructed from the ideas rattling around in Coppola’s head, which he never quite articulates gracefully into a narrative. Still, the film should not be deemed good or bad; it should only be discussed. (My choice of star rating reflects how unsatisfied I felt afterward, but also how the film gave me much to consider.) Admirable in that it’s unlike anything I’ve seen, the film’s chaotic haze eventually recedes and allows the director’s yearning for a better future to emerge. Achieving a utopia may be impossible, but yearning for one has symbolic value. This is what America—and Megalopolis—is all about in Coppola’s view. Once we stop learning from the past and striving to improve the world, history will continue to repeat itself.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review