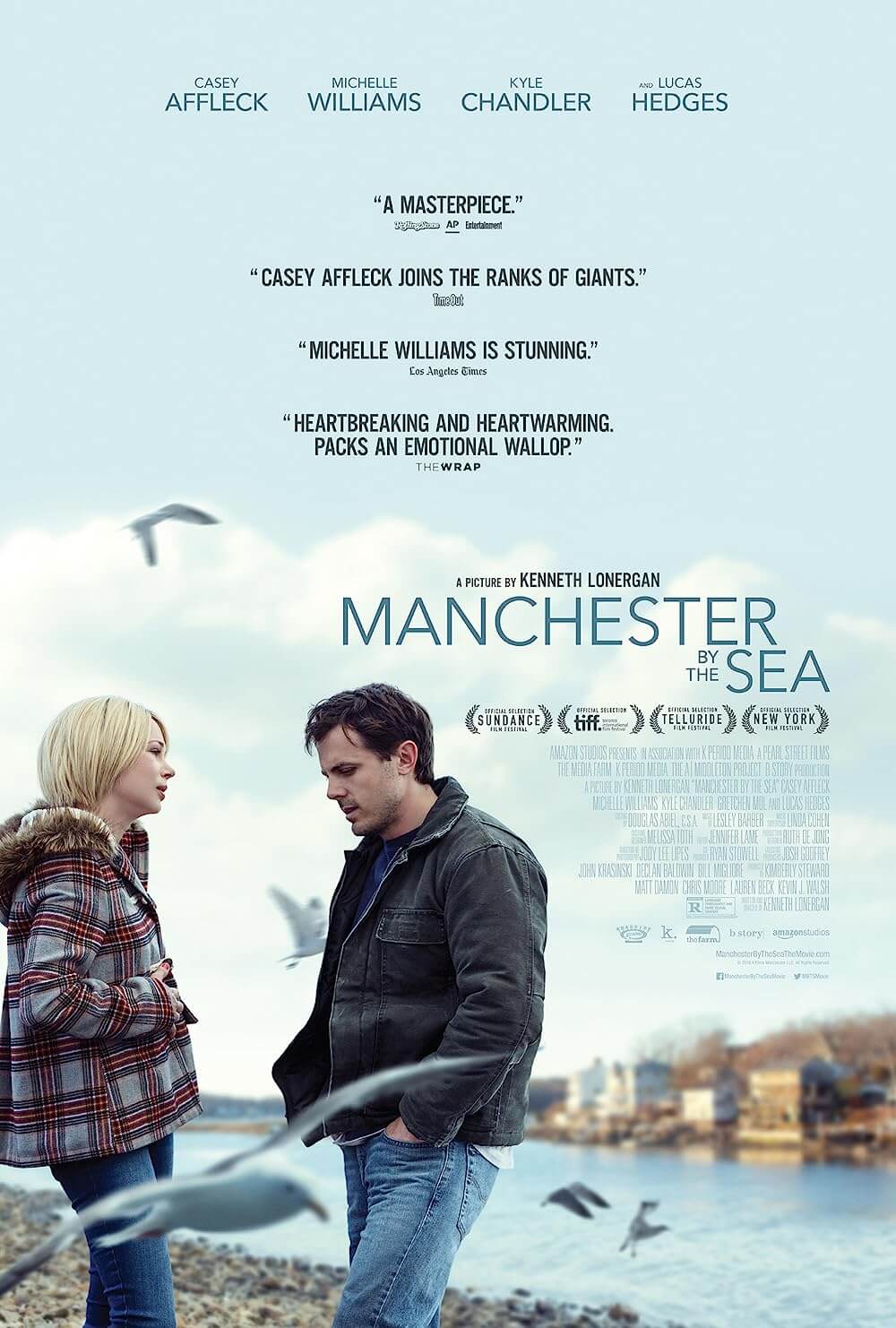

Manchester by the Sea

By Brian Eggert |

Textured by the substance of humanity, Manchester by the Sea dwells on the inelegance of real-life interactions during times of grief and disorder. Written and directed by Kenneth Lonergan, the heart-wrenching picture features Casey Affleck in a raw performance as a Bostonian who must return to his hometown to suffer tragedies new and old. While the core of the story may seem deceptively familiar, Lonergan’s ear for authentic and penetrating dialogue provides a number of unexpected laughs for a film covered in scars and stripped bare. Indeed, there’s nothing prototypical here, as the film’s capacity for vulnerability and naturalism bonds its audience to the material. And after the film has ended, the hold of Lonergan’s transportive effect requires time to wear off; like eyes adjusting to the light after a long spell of darkness, its lasting powers subside only after a considerable amount of time away from the film.

A playwright and frequent script doctor, Lonergan made his directorial debut in 2000 with the Oscar-nominated family drama You Can Count On Me, and later released Margaret in 2011, but only after five years of production and legal troubles. Margaret co-star Matt Damon helped produce Manchester by the Sea and was originally slated to star, until Damon backed out in favor of Affleck. Shot for just over $8 million, the film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival, where Amazon Studios purchased the distribution rights for a whopping $10 million. After supporting filmmakers such as Spike Lee, Whit Stillman, Nicolas Winding Refn, Woody Allen, and Park Chan-wook with similar distribution deals over the last year, Amazon again finds themselves in good company with a distinct directorial voice.

Lonergan’s film taps into a well-established tradition of stories about Irish Catholic men from Massachusetts who guard their feelings and turn punchy if tested, or even for no reason at all. Titles such as Good Will Hunting, Mystic River, The Departed, The Town, The Fighter, and Gone Baby Gone channel the rugged exterior of middle-class white men seemingly incapable of communicating on emotional terms, unless they’re under extreme duress. Typically, such characters are not as privileged as those in Manchester by the Sea, which settles on a family with a thriving commercial boat business, a paid-off mortgage, and seemingly few other financial difficulties. And yet, their lives are mired by death and crushing events that have shaped their choices and ruined any hope of becoming whole again. What’s rare is how conscious Lonergan’s characters are about their state of emotional disrepair.

Lonergan’s film taps into a well-established tradition of stories about Irish Catholic men from Massachusetts who guard their feelings and turn punchy if tested, or even for no reason at all. Titles such as Good Will Hunting, Mystic River, The Departed, The Town, The Fighter, and Gone Baby Gone channel the rugged exterior of middle-class white men seemingly incapable of communicating on emotional terms, unless they’re under extreme duress. Typically, such characters are not as privileged as those in Manchester by the Sea, which settles on a family with a thriving commercial boat business, a paid-off mortgage, and seemingly few other financial difficulties. And yet, their lives are mired by death and crushing events that have shaped their choices and ruined any hope of becoming whole again. What’s rare is how conscious Lonergan’s characters are about their state of emotional disrepair.

The story opens on a fishing boat named Claudia Marie as it ambles along under the overcast skies of Manchester-by-the-Sea. Joe (Kyle Chandler) captains the boat, while his brother Lee (Affleck) teases his young nephew about the potential of sharks in Cape Ann. The scene takes place in a past that must seem achingly distant to Lee, who serves as a handyman in Boston in the present-day. An evidently broken man, Lee would rather start a bar fight than engage with a woman interested in taking him home. His reasons for remaining so miserable linger even after Lee receives a call and rushes back to his hometown, just missing the death of his brother. Joe has long endured under a grim diagnosis of congestive heart failure, so his death comes as no shock, but at the same time it’s completely unexpected for Lee.

Faced with catatonic grief even before Joe’s death, Lee must endure hospital officialdom, dreary conversations about funeral arrangements, and questions about the future of his now-teenaged nephew, Patrick (Lucas Hedges). As it turns out, Joe’s will states that Lee must become Patrick’s legal guardian, a detail to which Lee responds, “But I was just a back-up.” For the film’s duration, the audience wonders if Lee will become capable of his new task, given his closed-off state. Even locals remark about Lee to one another (“That’s the Lee Chandler?”), all of them aware of Lee’s past, a secret kept from the audience, that makes his presence strange. At any moment during one of Lee’s brooding stares, flashbacks into his memory reveal that he wasn’t always such an ill-tempered guy. We see him good-humored with his former wife, Randi (Michelle Williams), in a casual household sequence that reveals how the now-divorced couple seemed to have a child around every corner. What happened to his family, and is Lee able to recover to take care of Patrick?

Affleck has only been better once, as the longing admirer of Brad Pitt’s famous gunslinger in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. His interminable numbness throughout Lonergan’s picture draws dimension from flashbacks to the mistakes of Lee’s past, the film’s enduring tragedy that the writer-director never washes over with some artificial, cathartic resolution. Affleck carries his wounds under the surface, and in the face of the internalized performance, the actor manages to evoke incredible emotion through his walled exterior. Rare expressions of dry humor or furious outbursts accompany Lee’s long silences, lending a sense of hope that the character may still heal and become the father figure Patrick needs him to be. But Lonergan seems more interested in exploring the pain of someone fully broken, and Affleck communicates that beautifully.

Meanwhile, Williams eviscerates in her few scenes, in particular during an unexpected reunion between Lee and Randi that shows us the wounds both characters have been carrying around. Lee can barely speak and refuses to connect, while Randi falls apart from regret. And if the person next to you doesn’t have tears streaming down their face during this scene, then they may be a robot or alien, or some combination thereof (either way, don’t trust them). It’s an exchange where almost nothing of substance is said between them; but both characters seem incapable of communicating their pain in any graceful way. So much is touched by the actors in this moment, feeling their way through what will become the film’s most memorable scene. Elsewhere, Gretchen Mol brings the same unbalanced degree of motherly obsession she offered in HBO’s Boardwalk Empire to Patrick’s alcoholic mother, working alongside a brief appearance by Matthew Broderick as her new fiancé. Chandler also delivers a strong turn in one of his many father roles, though his scenes are entirely in flashback.

Meanwhile, Williams eviscerates in her few scenes, in particular during an unexpected reunion between Lee and Randi that shows us the wounds both characters have been carrying around. Lee can barely speak and refuses to connect, while Randi falls apart from regret. And if the person next to you doesn’t have tears streaming down their face during this scene, then they may be a robot or alien, or some combination thereof (either way, don’t trust them). It’s an exchange where almost nothing of substance is said between them; but both characters seem incapable of communicating their pain in any graceful way. So much is touched by the actors in this moment, feeling their way through what will become the film’s most memorable scene. Elsewhere, Gretchen Mol brings the same unbalanced degree of motherly obsession she offered in HBO’s Boardwalk Empire to Patrick’s alcoholic mother, working alongside a brief appearance by Matthew Broderick as her new fiancé. Chandler also delivers a strong turn in one of his many father roles, though his scenes are entirely in flashback.

Hedges demonstrates surprising naturalism after two stylized turns with Wes Anderson (Moonrise Kingdom, The Grand Budapest Hotel) and one with fabulist Terry Gilliam (The Zero Theorem). The young actor captures adolescent life in all its petulance and overconfidence without reducing his character to an annoying teen. Lonergan writes a lively portrayal, as Patrick has a rich social existence; he has lots of friends, plays hockey, sings and plays guitar in a garage band, and volleys between two girlfriends. His scenes opposite Affleck contain hilarious sarcasm and pain thanks to the script, but delivered with such pitch-perfect timing thanks to the actors—all recalling that first scene on the fishing boat. When Lee cuts his hand after punching out a window, Patrick asks what happened, noticing the bloody bandage. “I cut my hand,” responds Lee flatly. “Oh, thanks,” says Patrick. “For a minute there I didn’t know what happened.” Such disarming humor pervades the film but never betrays the gravity of the material.

Then again, Lonergan preserves an almost funerary tone throughout Manchester by the Sea, permeated by Lesley Barber’s score of Baroque music by George Frederick Handel and Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni. Such winding classical organs may seem out of place in a thoroughly modern story, but they emphasize the drama’s theatricality and curious dynamic of comedy and tragedy maintained by the filmmaker. Also deceptively appropriate is Jody Lee Lipes’ cinematography that captures the intimacy on the actors’ faces without feeling too reliant on close-ups, as television camerawork often does. The lensing is all the more immersive on a big screen, in spite of the close-ups, because it lends a grandiosity to the intimate storytelling.

Lonergan balances unrecoverable anguish with tender warmth in Manchester by the Sea, a film that considers a character unable to forgive himself and hesitant to engage with anyone ever again. Regardless of the living, breathing quality of the characters and their searing pain, the film always finds ways to produce a laugh. Consider an almost farcical moment at Joe’s wake where reliable family friend George (C. J. Wilson) shouts across a crowded room at his wife about whether Lee has eaten today. Lonergan revels in simple, clumsy moments like this, which don’t play like a typical drama but instead unfold with the authenticity of everyday life. It’s not a film about happy endings and people putting the past behind them; it’s about how memories prevail and define us. Sometimes they make us stronger and we move onward, but sometimes they scorch our minds and remain cinders even after we’re reduced to ashes, dying down but never fully burning out.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review