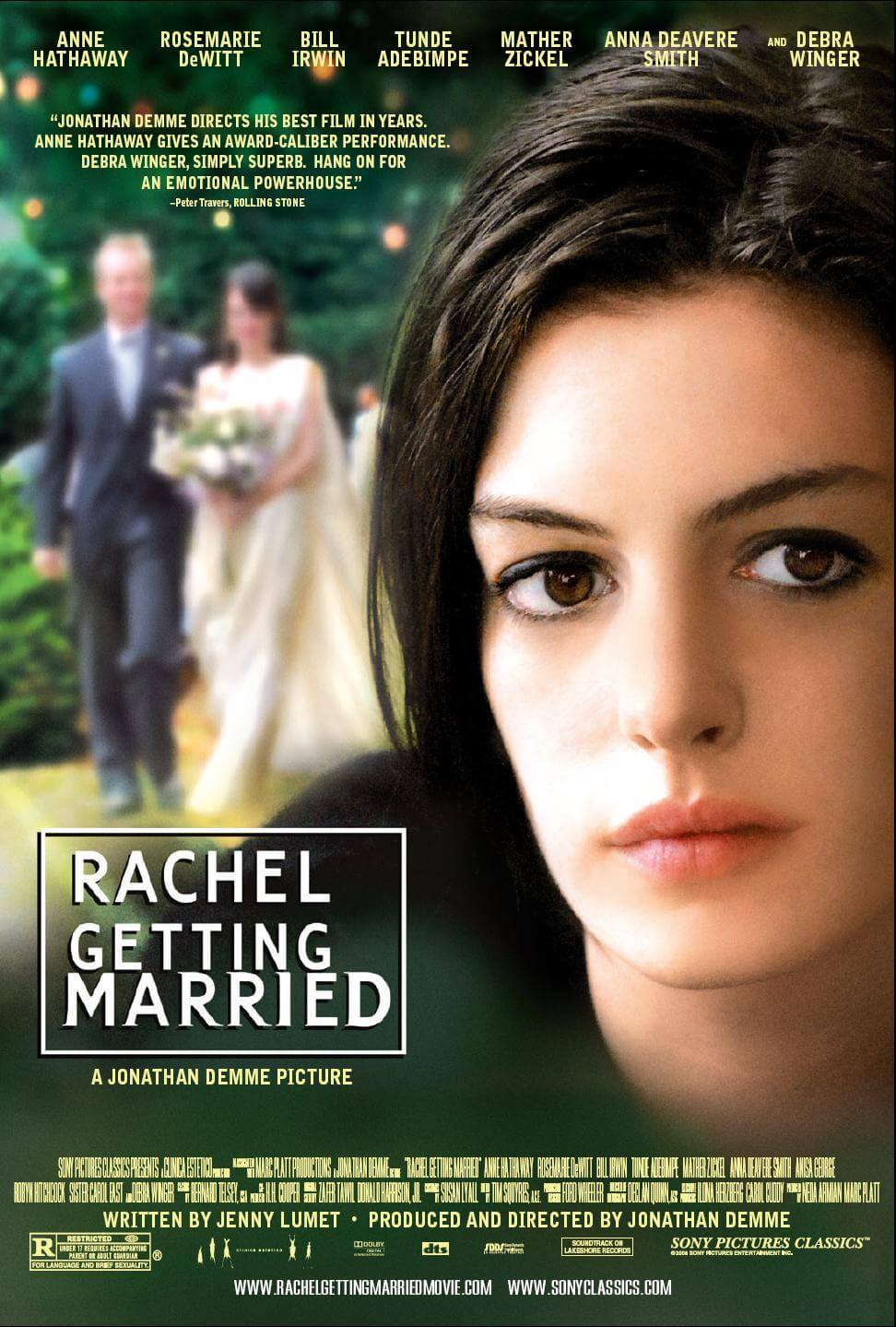

Rachel Getting Married

By Brian Eggert |

Welcome to the family. Make yourself at home. This weekend should be one to remember. A beautiful but cozy gala is arranged by the bride and groom, filled with culture, poetry, and even some Neil Young inserted into the vows. Friends are scattered about, talking, playing sitar and violin, capturing the moments on digital video for happy reflection later on. The families are meeting for the first time. It’s hard to ignore their evident dysfunction, but they love each other. That’s the important thing. So have a drink and something to eat. There’s plenty of food (and thus, plenty of dishes to maneuver into the dishwasher).

Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married contains an impressive quality of dramatic realism, even if sections could be safely classified as melodrama, all set around the weekend encasing a Connecticut marriage. Comparisons will no doubt be made to the extended wedding sequences in The Deer Hunter and The Godfather, but Demme’s service is more personalized. Cinematographer Declan Quinn captures the events like that individual at family functions who can’t put the camera down—a character the film makes sure to point out, if only to make us accustomed to the idea of a captured occasion, and further our experience of being placed in the moment.

We observe every conversation and inevitable argument, almost unsettled by the three-dimensionality of the portrayed family. As you’ve likely guessed, Rachel (Rosemarie DeWitt) is the bride. She’s marrying Sidney (TV On The Radio’s Tunde Adebimpe). But the central character is Rachel’s sister Kym (Anne Hathaway), fresh out of her most recent stint in rehab, overwrought with pressure, guilt, and feelings of persecution. Her father, Paul (Bill Irwin), keeps a concerned and watchful eye, always making sure she’s well-fed, while her stepmother Carol (Anna Deavere Smith) takes a background role as stepmothers often do. Kym seems needy for attention, even through vilification, so she’s offended when attention goes to Rachel.

There’s more to Kym, of course—an involved history that could register like a case study when described. She’s remorseful for reasons I won’t divulge in this review, and so her world revolves around little more than her own recovery. Whether or not she’s a recovering addict or still a full-fledged junkie remains to be seen; maybe she’s somewhere in the middle. Her presence shakes things up, but not in the pleasant way a wedding procession should be shaken up. During the rehearsal dinner, a microphone is passed around, and everyone says their kind words, laughing amiably at the sentiments told. Kym takes the mic, and we shutter, knowing this Shiva will utter something awkward, trying to make light of her situation, which everyone in the room knows about, and she desperately needs to forgive herself for.

Hathaway gives Kym energy and life, playing her with equal parts victim and purveyor of her own misery. This is her best performance yet, and she deserves recognition for her impressive range. DeWitt is likewise wonderful as the wife-to-be, capably shifting her focus from the wedding to veiled and confused feelings about her sister’s presence there. Debra Winger makes a welcomed return as their estranged and distant mother, whom they both look up to, but who can’t seem to offer genuine love for either anymore. And then there’s Irwin as the father, a potent and sensitive role, we realize, as the film slowly reveals his fragile and loving nature.

Jenny Lumet, director Sydney Lumet’s daughter (Network, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), wrote the script. But I’m unwilling to reduce the presentation of this kind of film into a script and would prefer that the result simply exists as a slice of life, complete with a pulse and bittersweet heart. Admittedly, I found the interaction of characters troublingly authentic, in that we’re penetrated so deeply by where the film goes, unable to disconnect art from participation. Like any service of this kind, we’re consumed by it, lost among a myriad of faces. Some are familiar; we feel close to them, even amid their arguments, ranging from petty to monumental. Others are smiling faces there for a good time.

Paying tribute to Robert Altman through an homage of informal framing, a mosaic of characters and their overlapping dialogue, and casual formal presentation, Demme’s film has more class and artistry than anything he’s constructed in years. Once the filmmaker behind clever and quirky pictures like The Silence of the Lambs, Something Wild, and the Talking Heads concert documentary Stop Making Sense, his talent has dissipated into the humdrum: remakes of Charade (renamed The Truth About Charlie) and The Manchurian Candidate, along with a placid documentary about Jimmy Carter.

Demme’s career path comes full circle with Rachel Getting Married, returning his talents to the realm of artistic entertainment. Engaging us with these characters, Demme occasionally tests our reactions by inciting anger or frustration with their behavior. But we only react this way because we’re so completely involved because we’ve gradually begun to care. Jarring as the experience can often be, the film may upset some viewers, particularly those with family not in the habit of communicating. For the rest of us, engrossed in the event’s highs and lows, we revel in Demme’s capable hands and the pathos of his ceremony.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review