The Definitives

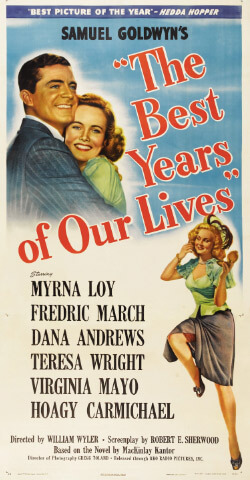

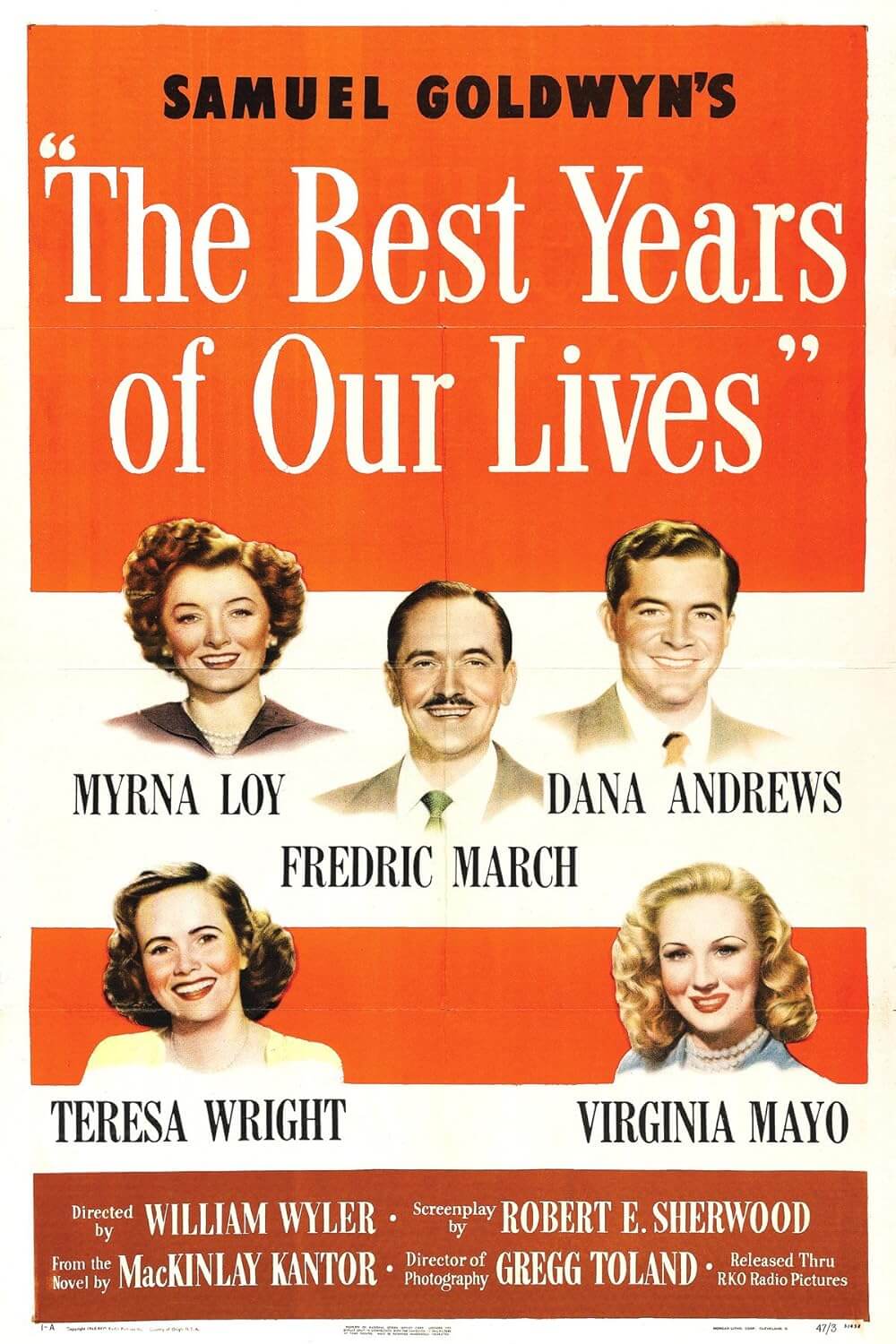

The Best Years of Our Lives

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The Best Years of Our Lives blends Hollywood melodrama and restrained, observational form to treat its subject with critical realism and humanity. William Wyler’s film captures the lives of three returning World War II veterans from different social classes, the changes to their country and loved ones during their time away, and the adjustments they must undergo to transition back into civilian life. In an early scene, the central characters take the same transport flight home, and along the way, share stories about their families and experiences, and about how each of them suffers from psychological or physical wounds. They pass over an airplane boneyard and look down on a sea of bombers destined for the scrap heap. In elegant and economic terms, the image anticipates how each man will feel or be treated upon his return, like old, inessential equipment that no longer has a purpose. A dramatic triptych unfolds to reveal a portrait of postwar American culture: a precise historical moment captured through deeply human and naturalistic storytelling, which critiques how America welcomed returning soldiers with class division, inadequate resources, and social disparity. Through its critical depiction of complex characters in a manner more commonly associated with literature than motion pictures, The Best Years of Our Lives remains so singularly honest in its description of veterans that Wyler’s treatment cannot help but supply an editorial on the social landscape of postwar America.

The Samuel Goldwyn production debuted in late 1946, just as millions of veterans returned to unfortunate circumstances: The war had not brought peace. The relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union was falling apart, and the Cold War was ramping up; there was a civil war in China; and after the U.S. dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the power of atomic energy and the prospect of nuclear war terrified everyone. American soldiers returned to a country whose conservative politicians argued that fighting the Nazis and Japanese was unnecessary, falling back on the same isolationist stance that nearly overcame the country before the bombing of Pearl Harbor finally committed the Roosevelt administration to war. Even after the war, some called America’s participation part of a Jewish plot, using Anti-Semitic rhetoric to spread fear about the Communist presence in America, especially Hollywood (Congressman John Rankin, a conservative Democrat from Mississippi, attributed the cause of the war to “a little group of our international Jewish brethren”). As the Cold War emerged instantly after the Second World War, the once-temporary House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), created in 1938 to expose disloyalty on American soil in the wake of growing threats on the international stage, became a regular fixture in American politics and culture for the next two decades.

Meanwhile, millions of American families tried to return to normal, but normal had changed. Problems of demobilization and reintegration of soldiers into civilian life affected every member of the so-called Greatest Generation. Women who had entered the workforce were expected to become homemakers again. Although marriage rates had increased wildly with the volume of returning servicemen, leading to the Baby Boom, so had divorces. Women wanted to keep working and thinking of themselves as individuals, and when their husbands came home from war and expected their wives to return to their old gender roles, some women left. At the same time, America had learned a hard lesson after World War I when thousands of soldiers returned from overseas to find themselves jobless and homeless, leading to the Bonus Expeditionary Forces March on Washington, D.C. in 1932. Truman’s administration had tried to prevent another postwar transitional disaster by establishing job programs, but they failed to protect returning soldiers adequately. Over half of the country’s unemployed in 1946 were veterans, and even those veterans who were employed often had to settle for lesser-paying jobs or positions that did not suit their abilities. Moreover, some civilians had stigmatized returning soldiers, worrying that they would take up the available jobs. All the while, the psychological strain on veterans was quietly disregarded. What was called being “shell-shocked” or “battle fatigued” after World War I became a “gross stress reaction” in the 1940s. The term post-traumatic stress disorder would not be used until the 1970s to describe Vietnam veterans. As critic Abraham Polonsky observed, “veterans had been sold out en masse by society.”

The Best Years of Our Lives started with producer Samuel Goldwyn, Hollywood’s most renowned independent producer at the time, matched only by David O. Selznick. Development on the project began in August 1944, and the finished film premiered eighteen months later in November 1946. As the story goes, Goldwyn read an article in a 1944 issue of Time magazine, recommended by his wife, called “The Way Home,” about a group of First Marine Division veterans who experienced combat fatigue and needed a period of readjustment after returning from Guadalcanal. Goldwyn hired novelist MacKinlay Kantor to write a treatment based on the article. Kantor, who would later earn the Pulitzer Prize for his Civil War novel Andersonville (1955), delivered his draft, called Glory for Me, in January 1945. The result was not the 100-page document that Goldwyn had ordered—it was a 268-page novel in blank verse. Although Goldwyn shelved the project after finding Kantor’s approach unintelligible, he later showed the novel to Wyler, who believed the film would promote empathy for servicemen returning to civilian life. Goldwyn then hired three-time Pulitzer winning playwright Robert E. Sherwood, a former speechwriter for Roosevelt, who had contributed to screenplays such as Idiot’s Delight (1939) and Rebecca (1940), to rewrite Kantor’s draft. After some additions from Wyler and Goldwyn, the screenplay was ready, and Wyler put together his ensemble, including Fredric March, Dana Andrews, and an actual wounded veteran Harold Russell in the central roles, while Myrna Loy, Teresa Wright, and Virginia Mayo filled out the supporting cast.

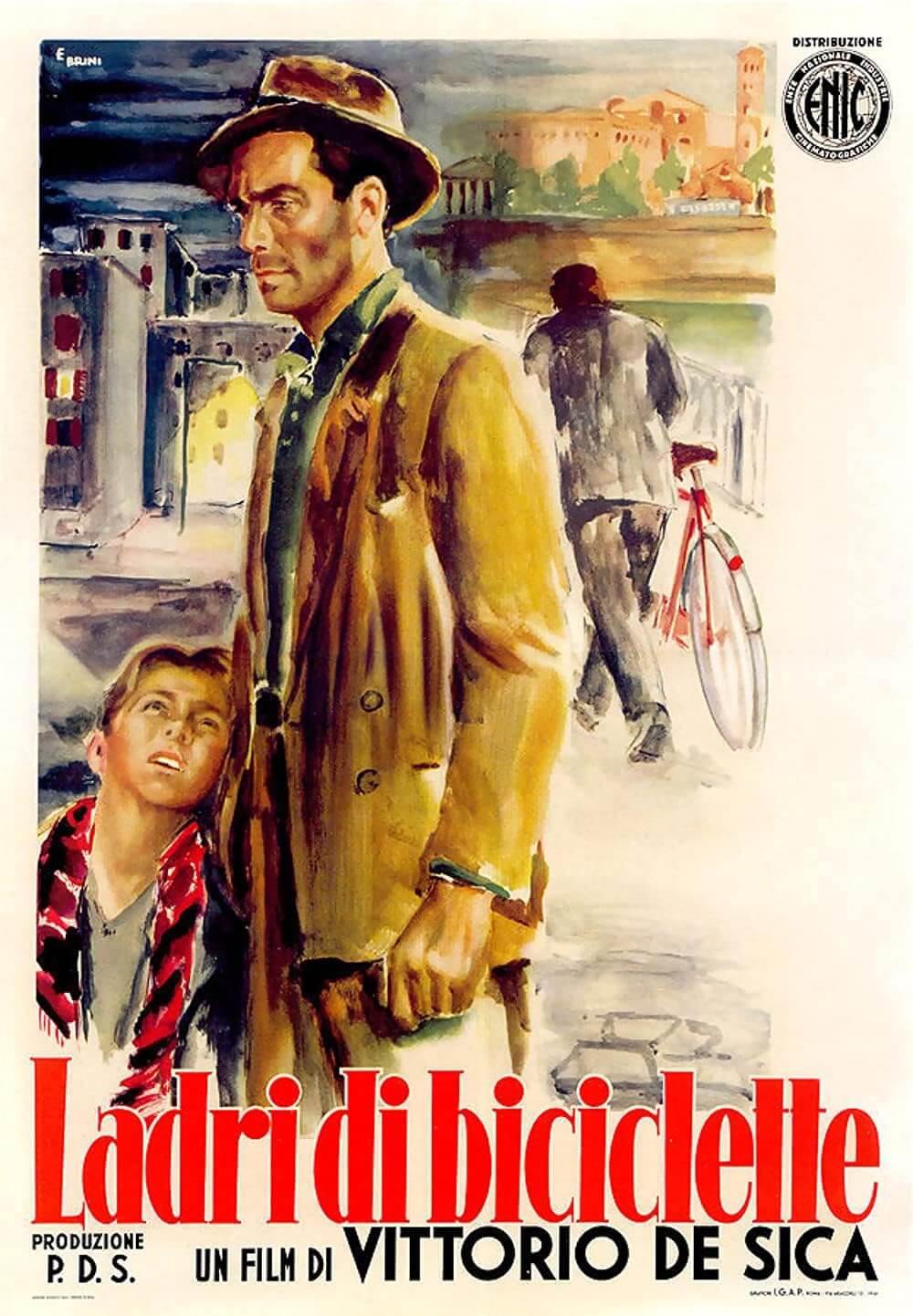

Although The Best Years of Our Lives became one of the highest-grossing releases of 1946, and it received seven Academy Awards, the film also breaks from traditional modes of production to deliver deeply personal filmmaking. Historically, one might be tempted to lump Wyler’s film together with other social problem releases from this era, but that would be a mistake; the film has more in common with Italian Neorealism, where its authentic stories and emotional narratives combine into an aesthetic markedly different from a traditional Hollywood picture. The film shares characteristics with Neorealist films like Bicycle Thieves (1948) or Umberto D. (1952), which shoot in a stripped-down style using actual locations and unprofessional actors. Yet, they have melodramatic stories and heightened emotional beats. They are not realistic in the fly-on-a-wall observational style associated with cinéma vérité, but they find truth through their poetry. The same is true of Wyler’s film, photographed by Gregg Toland in deep focus and deceptively simple blocking. But more than just realistic, the film was a rare personal expression by its director. Wyler had experienced World War II first-hand while shooting documentary footage, and when he returned from abroad, he recognized the characters depicted in Sherwood’s script. “I knew these people, shared a good many of their experiences,” Wyler said at the time. He had a pronounced empathy for returning veterans, and he felt artistically inspired to deal with their challenges in a realistic manner.

Wyler led the film’s drive toward authenticity. The director was among Classical Hollywood’s most accomplished filmmakers, averaging sometimes two or three features per year throughout the 1930s. He worked with Goldwyn almost exclusively between 1936 and 1941, and together, they made several respectable classics from the era, including Dodsworth (1936), Dead End (1937), Wuthering Heights (1939), and The Westerner (1940). His talents remained in high demand; Goldwyn loaned him out to Warner Bros. to direct Jezebel (1938) and The Letter (1940), both starring Bette Davis. And when the otherwise isolationist United States was drawn into World War II with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Wyler sought to help. Not only did he feel compelled to fight for the country that had been so good to him after moving to the U.S. from Alsace-Lorraine in his younger days, but given his origins in a Jewish family in Europe, he felt compelled to fight against Nazism and the Anti-Semitic fever emerging overseas and at home. His first wartime effort became Mrs. Miniver, a melodrama that sought to portray the British ordeal in the Blitz. Though widely celebrated by American audiences and at the Academy Awards—Mrs. Miniver was the top box-office performer of 1942 and also earned six Oscars, including Wyler’s first of three Best Director statues—that was not enough. Wyler enlisted in the Army, an experience he would later call, “an escape to reality.”

Just days after finishing work on Mrs. Miniver, the director wired Washington D.C. to join the Army’s Photographic Division. Like other filmmakers of his day, he was determined to use his talents to capture footage of the war. After passing a physical and paying the price of a uniform, the army assigned him the rank of Major, and Wyler set off to war with a hand-picked crew of Hollywood technicians behind him. He had orders to make films about the Eighth Air Force for training, morale, and historic purposes. Soon enough, Wyler had his first experience flying in bombing raids, and he realized that his Oscar-winning picture Mrs. Miniver got it all wrong; it was fluff, but what he was experiencing was real. The tough filmmaker never backed down from the assignment, however, regardless of some opposition. General Ira C. Eaker, realizing that Wyler was the Jewish director behind Mrs. Miniver, a film the Nazis hated given its popularity, sought to ground the director, fearing that Wyler might receive some particularly cruel treatment should he be captured on a mission. Wyler refused, even though he could have been court-martialed for his decision. It would not be the last time Wyler faced a court-martial during his service. In 1944, he narrowly avoided arrest when, in Washington, after an angry bellman called a customer “one of those goddamned Jews,” Wyler slugged him.

Wyler’s experiences in the war resulted in two documentary features. The first, The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress (1944), followed the missions of a Boeing B-17. Shooting the film was no cushy assignment, however; to get the footage seen in the documentary, Wyler accompanied the Air Force crew on several missions at considerable personal risk. Later, he personally screened it for President Roosevelt, who declared that every American should see the film. The second of Wyler’s wartime documentaries, Thunderbolt! (1947), was made alongside John Sturges (Bad Day at Black Rock, 1955). It charts the missions of a P-47 fighter-bomber squadron over Italy. Although Wyler later earned the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and received the Legion of Merit in 1946 after completing the film, his experiences shooting Thunderbolt! left him permanently deaf in his right ear. At first, Wyler’s hearing loss was total, and he was unsure whether he would ever hear again. The Army shipped him to a hospital in Santa Barbara, where he underwent questionable treatment and countless tests. The Army hospital was hardly a welcoming, healing sanctuary. They gave him sodium pentothal, better known as a truth serum, to determine if his hearing loss was merely psychosomatic, and they also kept Wyler in a padded cell. He became depressed and felt isolated in a world where he could neither hear nor receive the treatment he needed, and he worried if he would ever make another film. Over time, partial hearing in Wyler’s left ear returned, but he remained traumatized by the experience, both physically given his hearing loss and psychologically from his care at the treatment center. Afterward, he received sixty dollars a month from the U.S. government for his affliction.

Discharged in December 1945, Wyler returned to Hollywood. He joined the ranks of several veteran-filmmakers who worked for the United States propaganda machine, often catching actual war footage for use in military training films, newsreels, and historical records. And not unlike John Ford, Frank Capra, George Stevens, and John Huston, Wyler would approach Hollywood filmmaking in a different light given his new perspective. Now informed with documentary and observational techniques, not to mention an eye-opening exposure to the unromantic reality of war, all far removed from the artifice of Hollywood, the output of these filmmakers changed after the war. Stevens, for instance, once known for blithe comedies, returned from his experiences and made cynical films like A Place in the Sun (1951) and The Diary of Anne Frank (1959). Capra confronted corruption and hopelessness with his aching but optimistic It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Having one more film in his contract with Goldwyn, Wyler saw Kantor’s draft of Glory for Me and resolved to film it. Goldwyn wasn’t enthusiastic and would have preferred that Wyler direct The Bishop’s Wife or a rousing biopic about General Eisenhower. But Wyler was attracted to the idea of a film about the average grunt and not an iconic general. Sherwood and Goldwyn met with the director, whose experience in battle and postwar disability left him particularly suited to the project.

As the plot goes, Wyler introduces three veterans flying home to their small town of Boone City, each from a distinct social class and division of the army. Their representative cross-section, one of the film’s few traits that reveal the delicate touch of Hollywood artifice, captures the social environment spanning postwar America. Al Stephenson (Fredric March), a sergeant who fought the Pacific island war against the Japanese, has an upper-middle-class wife and two older children waiting for him, as well as an established career in banking. Al is married to Milly, played by “The Perfect Wife” Myrna Loy, who was such a star because of her role in The Thin Man series opposite her on-screen husband William Powell that Goldwyn gave her top billing to convince her to take the small but crucial part. Fred Derry (Dana Andrew), a soda jerk before the war, comes from a destitute home under a bridge, but he returns a decorated Air Force lieutenant whose rushed marriage to Marie (Virginia Mayo) before the war begins to fall apart. Fred’s marriage becomes even more complicated when he meets Al’s daughter, Peggy (Teresa Wright), and they fall in love. Homer Parrish (Harold Russell), an enlisted man from the Navy, has lost both arms up to his elbows, leaving him with two prosthetic hooks. Although he has a loving family and devoted sweetheart, Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell), supporting him, Homer, self-conscious about his hooks and dependence on others for help, feels like he’s a burden. When the three veterans arrive home in Boone City, they share a taxicab that passes by children in strollers, Woolworth’s stores, and hotdog stands. Their hometown has continued to hum along without them.

Wyler’s commitment to authenticity begins with Russell, a wounded veteran and untrained actor. The director had seen him in a Signal Corps documentary called Diary of a Sergeant (1945). Russell, a butcher before the war, served as a demolitions instructor at Camp Mackall in North Carolina, where a defective fuse caused TNT to explode in his arms, requiring a bilateral amputation at the elbows. Although he initially endured months of feeling useless, he soon accepted his situation, and his impressive rehabilitation landed him a role in the documentary. Wyler saw a natural personality and genuine screen presence during Russell’s demonstration of how to use his mechanical hands, and he sought out Russell for the role of Homer. Goldwyn wanted Farley Granger to play Homer and, initially, worried that Russell’s inexperience might spoil the film’s dramatic potential. Goldwyn put Russell into acting lessons without Wyler knowing. But when the director found out, he fumed. He wanted a natural presence for Homer, not someone performing for the camera, and immediately canceled the lessons. After all, Homer’s disfiguration remains the most confronting aspect to the movie-going audience, since disabling conditions of this kind remained hidden from the public eye or treated as an unrecoverable tragedy. Wyler considers the issue from the wounded soldier’s perspective, and Russell’s unpolished performance rings with feeling. On the plane to Boone City, Homer worries about what will happen when he returns home, and whether Wilma will accept him. When he’s reunited with his family, Homer’s mother cries at the sight of his new hands, whereas Wilma never shows anything but loving acceptance. She hugs Homer, whose arms remain at his sides. Watching this reunion from the taxi, Fred observes how the Navy “sure trained him to use those hooks,” but Fred adds, “they couldn’t train him to put his arms around that girl.”

Homer’s entangled character alternates between feeling like a monster and a castrated man. In one sequence, a group of children watch Homer through a window, snickering and whispering about his hooks and his engagement to Wilma. His knee-jerk reaction feels like a true moment from an otherwise inexperienced actor. “Do you wanna see how the hooks work?” he shouts. “Do you wanna see the freak?” He smashes his hooks through the window, frightening the children. Elsewhere, Wyler included scenes where Homer lights a cigarette or plays piano with his hooks not to exploit the reality of Homer’s situation but to inform and normalize. The wounded soldier is not helpless; he can get around and function, yet people treat him and see him as infirmed. Homer’s story, based in part on Russell’s experiences, considers the psychological toll of such treatment. Those who behave toward Homer like a woeful case and refuse to accept his new hands prove more troublesome for Homer than living with his condition. It takes Homer revealing his nighttime routine to Wilma before he can trust that he will not hold her back or become a burden. He removes his hooks and the body harness that keeps them attached. “This is when I know I’m helpless,” he begins an openhearted speech. “My hands are down there on the bed. I can’t put them on again without calling to somebody for help. I can’t smoke a cigarette or read a book. If that door should blow shut, I can’t open it and get out of this room. I’m as dependent as a baby that doesn’t know how to get anything except to cry for it.” The scene required finesse and tenderness to meet all the demands of the Production Code, which rarely allowed for two unmarried young people to be together in a bedroom, much less one of them removing his pajama top and hooks. It remains a layered interaction, as film historian Sarah Kozloff notes that, under the surface, Homer worries he cannot fulfill the typical duties of a husband. The scene emphasizes how many veterans in Homer’s condition felt: unworthy of love compared to someone normal. Nonetheless, Wilma shows she is willing to try; she loves him, hands or no. Finally, Homer hugs her.

Homer’s entangled character alternates between feeling like a monster and a castrated man. In one sequence, a group of children watch Homer through a window, snickering and whispering about his hooks and his engagement to Wilma. His knee-jerk reaction feels like a true moment from an otherwise inexperienced actor. “Do you wanna see how the hooks work?” he shouts. “Do you wanna see the freak?” He smashes his hooks through the window, frightening the children. Elsewhere, Wyler included scenes where Homer lights a cigarette or plays piano with his hooks not to exploit the reality of Homer’s situation but to inform and normalize. The wounded soldier is not helpless; he can get around and function, yet people treat him and see him as infirmed. Homer’s story, based in part on Russell’s experiences, considers the psychological toll of such treatment. Those who behave toward Homer like a woeful case and refuse to accept his new hands prove more troublesome for Homer than living with his condition. It takes Homer revealing his nighttime routine to Wilma before he can trust that he will not hold her back or become a burden. He removes his hooks and the body harness that keeps them attached. “This is when I know I’m helpless,” he begins an openhearted speech. “My hands are down there on the bed. I can’t put them on again without calling to somebody for help. I can’t smoke a cigarette or read a book. If that door should blow shut, I can’t open it and get out of this room. I’m as dependent as a baby that doesn’t know how to get anything except to cry for it.” The scene required finesse and tenderness to meet all the demands of the Production Code, which rarely allowed for two unmarried young people to be together in a bedroom, much less one of them removing his pajama top and hooks. It remains a layered interaction, as film historian Sarah Kozloff notes that, under the surface, Homer worries he cannot fulfill the typical duties of a husband. The scene emphasizes how many veterans in Homer’s condition felt: unworthy of love compared to someone normal. Nonetheless, Wilma shows she is willing to try; she loves him, hands or no. Finally, Homer hugs her.

If Homer’s story, which ends The Best Years of Our Lives on a pleasant note, with Homer and Wilma’s marriage, represents the film at its most optimistic, Al’s story fulfills another kind of arc. Married for twenty years, Al returns to an idyllic nuclear family and a new job as vice president of small loans. But his teenage son, Rob (Michael Hall), schools him on the threat of atomic energy and seems uninterested in Al’s gifts of Japanese artifacts—a samurai sword and blood-stained flag—that might have delighted a younger boy. Milly no longer recognizes him; though, their marriage has lasted this long out of their commitment to support one another. Instead, Al’s main struggle comes at the bank. His boss, Mr. Milton (Ray Collins), questions Al’s choice to grant a loan to a fellow veteran with no collateral. Al argues, “His ‘collateral’ is in his hands, in his heart and his guts,” that the veteran’s financial integrity is not something to be measured on a loan application. After a slight reprimand, Al resigns himself to the bank’s policy, and the gracious smile on Milton’s face drops when Al leaves his office. Even so, in a later scene at a banquet arranged by the bank in his honor, Al stands to give a speech that signals his divided loyalty to the Cornbelt Loan and Trust Company and his fellow soldiers in need of credit: “There are some who say that the old bank is suffering from hardening of the arteries and of the heart,” Al says, wobbly. Throughout the evening, Milly has kept an eye on his drinking, scratching a line in the tablecloth with a fork for each cocktail. “I say that our bank is alive,” he continues. “It’s generous, it’s human. And we’re going to have such a line of customers seeking and getting small loans that people will think we’re gambling with the depositors’ money. And we will be. We will be gambling on the future of this country.”

Al’s torment proves more existential than Homer’s or even Fred’s, as it will be shown. He no longer recognizes his children; his relationship with his wife requires adjustment; he must conform to the new capitalist order at the bank, which contradicts everything he learned about trusting his fellow soldier on the battlefield. “Last year it was ‘Kill Japs,’ this year it’s ‘make money,’” he laments. Maybe Al has grown tired of taking orders, or maybe he realizes the bank is a metaphor for capitalism “hardening of the arteries” of America. Though he does not lose his job after his speech, he remains unhappy, and an alcoholic. Addiction to drugs and alcohol saw a rise in the postwar years, with millions of veterans turning to substance abuse for an escape. The Best Years of Our Lives finds each of its three central characters dependent on alcohol. Their first night back, the three men each end up at Butch’s, a local bar owned by Homer’s uncle (Hoagy Carmichael). Al is the life of the party, convincing everyone to have one more drink, stop at one more nightclub. Fred drinks so much that he passes out, and Peggy brings him home. Each man returns to Butch’s throughout the film, Homer so much so that his uncle tells him “to stay away for a while.” The sheer volume of Al’s drinking—matched only by William Powell in The Thin Man, albeit to comic effect—might be amusing given March’s animated performance, if not for Milly’s concerned looks. In the final scenes at Homer and Wilma’s marriage, Al and Milly seem content together, even if Al remains preoccupied with the wedding punch. Although male camaraderie often develops in drinking culture, the film acknowledges how this behavior not only supplies an escape from the pressures of domesticity, but it prevents the characters from making progress in their re-acclimation into civilian life.

While Homer’s adjustment involves his self-worth, and Al must compartmentalize his ideals to appease postwar America’s commitment to capitalism, Fred’s story confronts the psychological scarring that occurred in many veterans. Not unlike Homer, Fred has had his wings clipped, although not in the same manner—his mind has been traumatized by a malady even more stigmatized in American culture than a physical disfigurement. His first night back, sleeping off the bender in Peggy’s bed, he screams in terror from nightmares of his wartime experiences. Unlike his two counterparts, Fred has no family to support him. His parents live in a veritable shack on the wrong side of the train tracks, and he returns to find that his wife, Marie, has taken a hushed job at a nightclub and grown accustomed to a ritzy lifestyle. “All I want is a good job,” Fred declares, but he struggles to find one that pays well. He goes from soda jerk to bombardier to soda jerk again, resigning himself to his old position at the pharmacy, now a well-stocked general store. But Marie doesn’t want to wait for the good life, nor does she have the empathy to help her husband overcome his memories. “Can’t you get that out of your system?” Marie asks, annoyed by her husband’s PTSD. Before long, she leaves him for another veteran. Besides lowering himself to a sales position (he tells the store manager that he has no experience in procurement or personnel work, “I just dropped bombs”), he must endure a new attitude toward the war. One customer, an isolationist filled with right-wing rhetoric, claims the Nazis and Japanese had nothing against the United States, that the war was for “suckers.” Fred clocks him and loses his job in the process. The scene, inspired by Wyler’s near-court-martial for punching a bellman, originally included the customer’s Anti-Semitic slurs, but the Production Code office demanded their removal.

Fred’s case as a poor young man who enlisted because he had few other prospects was commonplace among veterans, and so was his effort to reorient and reconcile his trauma. “No one could go through that experience and come out the same,” Wyler told Hermine Isaacs in Theater Arts after the war. Peggy recognizes Fred’s condition, sees his fractured marriage and need for dignity, and she falls in love. She announces this to her parents and declares, “I’m gonna break that marriage up.” Peggy feels that her parents could not possibly understand Fred given their privileged lifestyle—a notion that underscores the film’s theme of class division—but she’s deflated when Al and Milly admit that no marriage is without ups and downs. “How many times have we had to fall in love all over again?” Milly reflects in a tender speech. In any case, Fred must overcome his own afflictions before he would be any good for Peggy. He resolves to leave town and, while waiting for a flight, he wanders the plane graveyard seen from above in the film’s opening scenes. Lost among endless rows of unusable machines, he climbs inside one of the bombers whose propellers have been removed just like Homer’s hands. Inside the nose, amid dusty switches, he relives his trauma. The sounds of battle reverberate in Fred’s mind, even as the scrapyard’s foreman tries speaking to him. In that instant, Fred seems to move beyond his experiences and push forward. He emerges from the bomber and talks his way into a job with the foreman, turning old planes into prefab houses—a symbol that Fred, alongside Peggy, will work together to build a life over his past trauma.

Although Al, Homer, and Fred remain at the drama’s forefront, Wyler also builds out the women of The Best Years of Our Lives into layered characters. Milly, Peggy, and Wilma take on the traditional roles often assigned to women in 1940s cinema, serving as wives and lovers. Each of them functions in a caretaker capacity to their men as well. But as Wyler’s body of work suggests—including Jezebel, Mrs. Miniver, The Heiress (1949), and Roman Holiday (1953), among others—he maintains an affinity for pictures about strong women, earning him the label of a “woman’s director” alongside George Cukor. The film’s longer-than-average runtime allows time for his women characters to be more than reductive types. Wilma’s patience and understanding of Homer’s malady reveal themselves in her sensitivity. Milly accepts that Al has changed in the war, and she will adapt, as she always has. Peggy, a modern woman, employed at a hospital (where she has learned “more than you or I will ever see,” Milly tells Al), refuses to be so patient. She loves Fred, and when she realizes Marie does not love him, her vow to break up his marriage is a stunning break from Production Code morals. Nevertheless, the women do not force their men to change, like so many mothers and wives, the moral epicenters of Classic Hollywood cinema: Milly cannot force Al to stop drinking; Wilma cannot make Homer forget about his hands; Peggy cannot heal Fred’s mind. The soldiers must do that themselves. Still, observe how each woman puts her man to bed in one scene. Through their nurturing, the film asks that we identify with their care of these damaged men, compelling a desire to treat returning veterans with empathy and support.

Wyler poured himself into the production of The Best Years of Our Lives like no picture before, and he worked closely with Sherwood and Toland to achieve the right dramatic tone and visual treatment. It was a notably personal production for a director often placed in charge of studio assignments, since Wyler could relate to each of his three main characters. Russell later called the film “Wyler’s heart and soul.” The director furthered his personal connection in subsequent drafts of the script. He had the most in common with Al (a supportive wife and good job waiting for him), and Al’s reunion with Milly was based on Wyler’s reunion with his own beloved wife, Talli, whom he was away from for over a year while overseas. But then, Wyler also related to Fred, a bombardier, given his experience on the Memphis Belle. Homer, like Wyler, had to acclimate to his new disability. Many of these touches were realized in Sherwood’s rewrite of Kantor’s original novel, whereas Sherwood omitted much of the Hollywood artificiality from earlier drafts, such as a sequence where Fred plans to rob a bank, only to have Al talk him out of it. And imagine how hollow it would have been had Al, following his arc from an early draft, left his job as a loan officer to work in a garden nursery. Sherwood also added Homer as an amputee, along with the screenplay’s anxiety about nuclear war and isolationist conservatives. The differences between Kantor’s text and the final screenplay are many, and the changes attest to Wyler’s need to craft a genuine and meaningful statement.

The production shot from April 1946 for seventy-two days on a budget of $2 million, wrapping in August. Today, some elements may seem unrealistic given our gritty, handheld conception of aesthetic realism, but The Best Years of Our Lives represented a major stylistic departure for Wyler or any Hollywood production. Wyler said at the time that he was part of a “conspiracy against convention” in stylistic terms. Filmed near Los Angeles, not in Cincinnati, as Goldwyn’s publicity department claimed, the director insisted on capturing actual city streets, airports, and the B-17 graveyard in Ontario, California. For the interiors, Wyler ordered the construction of intentionally smaller sets to look like real spaces, as opposed to the lofty Hollywood interiors with impossibly high ceilings that allowed cameras to maneuver. The actors wore less make-up than a typical production, and their costumes, purchased from department store racks, had a lived-in appearance because the principal actors had been wearing them for weeks before shooting began. Compared to most releases during the postwar era, the film’s authenticity appeared unorthodox and raw. Still, Wyler’s approach behind the camera remained the same. He furthered his reputation as “40 Take Wyler” by demanding take after take, a particular frustration for some actors given the film’s exceptionally long unbroken shots. Scenes that seem effortless and relatively inconsequential took the longest to shoot. Wyler saw no reason to break them up into shorter segments, so a modest but long scene, such as Al seeing Homer in the bank, reportedly took thirty takes to get right. Editor Daniel Mandell assembled the footage during the shoot, meaning post-production took only a few short weeks to finalize, including Hugo Friedhofer’s folksy score.

The Best Years of Our Lives marked the sixth and final collaboration between Wyler and Toland, who died in 1948. Together, they conceived a realistic aesthetic through a straightforward narrative, linear storytelling, modest camera movements, and deep focus photography—a far cry from the radical work Toland had done with Orson Welles. French theorist and critic André Bazin estimated that the film used only 190 shots per hour, about half of the average Hollywood film, due to Wyler’s insistence on long takes that immerse the viewer in the scene. Bazin’s study, one of the earliest to assess the film as Wyler’s masterpiece, argued that Wyler was not interested in emotional manipulation; he allows the viewer to see everything and make observations about what’s happening within in the frame. Bazin called Wyler’s approach an “invisible style” and noted that he makes it so “the spectator can (1) see everything; and (2) choose as he pleases. It’s an act of loyalty toward the spectator, an attempt at dramatic honesty.” Keeping the fore, middle, and background in focus enhances the effect, as does putting the action and reaction in the same shot, whereas a typical production might cut between them. Wyler’s deep focus staging is never more pronounced than in a bar scene where Homer and Butch play “Chopsticks” on the piano while Al watches. In the distance, Fred calls Peggy to tell her that he won’t see her again, a call that he promised to make at Al’s request. Al watches that too. Toland keeps all three figures in focus, and the scene parallels when the veterans sat at the same table in Butch’s earlier in the film, drinking together merrily, except now they are separated by spatial isolation and unspoken tension. Wyler’s interest in isolating his characters in visual terms led to his use of frames within frames: Al and Milly’s embrace at the end of a narrow hallway; Fred cramped in the bomber, reliving his trauma; Homer reuniting with his family from Al and Fred’s point of view through the cab window. Wyler understands that camera placement can involve the viewer by allowing us to search the scene and discover our own emotional reaction.

Indeed, The Best Years of Our Lives is not without emotional manipulation: when Wyler frames Homer looking out at a sunrise, or he catches Fred and Peggy’s eyes locked throughout Wilma and Homer’s wedding ceremony, he engages in sentimentalism that connected, and still resonates, with audiences in a profound way. At nearly three-hours with no intermission, the film does not align with what we now consider escapist or crowd-pleasing entertainment. Yet, it was the highest-grossing picture of 1946, after Song of the South, and followed by Duel in the Sun and The Jolson Story. With few exceptions, critics praised Wyler’s depiction of everyday life of a sort that rarely made it onto the screen. Bosley Crowther’s stirring review in The New York Times stated, “It is seldom that there comes a motion picture which can be wholly and enthusiastically endorsed not only as superlative entertainment, but as food for quiet and humanizing thought.” Everyone from General Dwight D. Eisenhower to anonymous servicemen wrote to Goldwyn’s company, thanking them for making such a true, human picture. Billy Wilder called it “the best-directed picture I’ve ever seen in my life.” Abroad, Bazin’s praise, which commends Wyler for the film’s “humility” toward his subject matter and audience, gave way to less generous assessments in the Cahiers du Cinéma in the 1960s, when Wyler’s filmography was associated with the contemptible “cinema of quality” against which New Wave filmmakers rallied. But at the Academy Awards ceremony in 1947, Wyler’s film resulted in Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (March), Best Supporting Actor (Russell), Best Film Editing, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Original Score. Much has been made about how Russell felt that his other Oscar that night, an honorary award for “bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans through his appearance,” was one too many.

Not everyone felt enthusiastic about Wyler’s film. A year after its release, HUAC’s investigation into Communism took a sharp look at Hollywood, and The Best Years of Our Lives became one target among many—during hearings that made accusations without evidence and unconstitutionally questioned political and ideological loyalties. HUAC chair J. Parnell Thomas, the Republican representative from New Jersey who delighted in making headlines, cited the film as Communist propaganda. The FBI delivered reports to J. Edgar Hoover about whether the film contained Communist messages. In a particular stroke of hypocrisy, the film’s representation of excessive drinking and divorce raised issues for the FBI, who believed that only Communists could be responsible for its displays of moral indecency. The bureau also questioned whether Howland Chamberlin (as the drug store manager), Roman Bohnen (as Fred’s father), and screenwriter Howard Koch (who allegedly contributed an uncredited rewrite) were Communists. All three would be blacklisted by 1950, along with dozens of others, when Hollywood’s top brass agreed to not knowingly employ Communists or “any disloyal elements”—reinforcing the blacklist in the wake of the Hollywood Ten’s citations, and jail time, for refusing to answer the committee’s questions. By 1947, over forty Hollywood actors, directors, writers, and others in the film industry were subpoenaed to Washington, D.C. before HUAC’s committee of demagogues. Any film or person who called for free speech, sought social justice, or questioned Americanism could be labeled a traitor or communist.

Wyler, backed by the Committee for the First Amendment, a coalition of Hollywood talent (including Fredric March and founding member Myrna Loy) who sought to defend the accused from HUAC, launched a counter-campaign. Wyler appeared on a radio broadcast called “Hollywood Fights Back,” where many spoke out against HUAC. “I’m convinced I wouldn’t be allowed today to make The Best Years of Our Lives as it was made a year ago,” Wyler said. “They are making decent people afraid to express their opinions.” Gene Kelly made an appearance on the broadcast as well. Kelly asked the audience if they had seen The Best Years of Our Lives. “Did you like it? Were you subverted by it? Did it make you un-American? Did you come out of the movie with the desire to overthrow the government?” The lasting effect of the HUAC hearings, coupled with separate hearings by Wisconsin’s Republican senator Joseph McCarthy about the Communist influence on American soil, led to a temporary blot on the film’s reputation and legacy. With HUAC’s antennae raised to any political views that questioned aspects of American culture, and Hollywood filmmakers self-regulating to avoid getting noticed, no bolder film about veterans than The Best Years of Our Lives would come out the postwar era. Not until decades later, after the end of HUAC and people started to confront the consequences of the Vietnam War, would countless films—including The Deer Hunter (1978) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989)—hope to confront the veteran experience. Among them, only Hal Ashby’s Coming Home (1978) comes close to achieving the unflinching humanity and internal realism of Wyler’s film. As Roger Ebert observed, “As long as we have wars and returning veterans, some of them wounded, The Best Years of Our Lives will not be dated.”

Though the concept of the American Dream emerged in the postwar era, Wyler’s film questions the illusion of American idealism, the stuff of highly regulated Hollywood motion pictures, family television, and cheery capitalism. The Best Years of Our Lives addresses the country’s failures through melodramatic circumstances and a precise, albeit observational style, offering three deeply personal stories that acknowledge realistic postwar human suffering and, by extension, sociopolitical despair in America. With his unobtrusive style and commitment to authenticity, Wyler avoids a Hollywood ending; his veterans’ troubles are not easily resolved, and not with undue cynicism. Even though Wyler loves his country, he knows it can do better. Given that The Best Years of Our Lives confronts the problems facing veterans, the title raises questions. Did these Best Years take place in the past, in the blissful ignorance before these men went to war? Are they the unrealized years at home that were lost during the war, and therefore represent something to be mourned? Fred tells Peggy, “the best years of my life have been spent.” She disagrees and claims their best years are still ahead of them. Instead of mythologizing the war and America’s victory, Wyler’s film refuses to concede to blind optimism, but he does offer hope. Only after confronting the reality of postwar America, in all its prospects and human failures, does the film embrace the healing possibilities of the future.

Bibliography:

Beidler, Philip D. “Remembering ‘The Best Years of Our Lives.’” The Virginia Quarterly Review, vol. 72, no. 4, 1996, pp. 589–604. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26439127. Accessed 17 July 2020.

Gerber, David A. “Heroes and Misfits: The Troubled Social Reintegration of Disabled Veterans in ‘The Best Years of Our Lives.’” American Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 4, 1994, pp. 545–574. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2713383. Accessed 19 July 2020.

Harris, Mark. Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War. Penguin Group, 2014.

Herman, Jan. A Talent for Trouble: The Life of Hollywood’s Most Acclaimed Director, William Wyler. Phantom Outlaw Editions, 2015.

Isaacs, Hermine Rich. “William Wyler: Director with a Passion and a Craft.” Theater Arts 31 no. 2, 1947.

Kozloff, Sarah. The Best Years of Our Lives. BFI Film Classics. British Film Institute, 2011.

–. “Wyler’s Wars.” Film History, vol. 20, no. 4, 2008, pp. 456–473. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27670746. Accessed 17 July 2020.

Miller, Gabriel. William Wyler: The Life and Films of Hollywood’s Most Celebrated Director. The University Press of Kentucky, 2013.

Polonsky, Abraham. “‘The Best Years of Our Lives’: A Review.” Hollywood Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 3, 1947, pp. 257–260. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1209411. Accessed 17 July 2020.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review