Maestro

By Brian Eggert |

Maybe it’s appropriate that I had trouble connecting with Bradley Cooper’s otherwise terrifically made new project, Maestro, about Leonard Bernstein. From the outset, in a quote from Bernstein himself, Cooper establishes the theme that art thrives on conflict: “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” This becomes true in Cooper’s biographical portraiture, which explores the musician’s many contradictions, from his artistic heights to his personal foibles. Cooper’s execution aesthetically and intellectually reflects the film’s stated purpose so that, like Bernstein, the filmmaking employs a mass of formal disparities, some thoughtfully applied and others so Mannerist that they prevented me from fully committing to the emotional experience Cooper meant to summon. These occasional flaws or failures, if you can call them that, only made me want to dig deeper into the experience—to understand what worked about the film and why what didn’t, didn’t. And yet, at times, I felt at a remove from Maestro, owing to the distancing effect his choices caused, and I cannot say it fully enamored me.

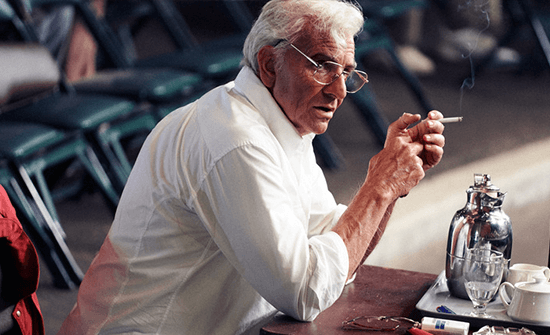

Then again, great art compels us to understand it. So many films today are either so straightforward as to be dull or fail to challenge us in compelling ways. Maestro is unquestionably a work of passion and deep consideration from a filmmaker who has poured himself into the lead role and the thoughtfully applied mise-en-scène. His film has been conceived and planned down to the last detail, with Cooper embracing his inner showman behind the camera to mirror his performance on screen. The method of Cooper’s ostentatious style evokes a classical Hollywood musical’s expressiveness, which aligns perfectly with Bernstein’s complex and conflicted personality. Even so, the production is filled with artifice: the prosthetic makeup to make Cooper look like Berstein, the elaborate camera work, and the stagey performances—all of which call attention to themselves, resulting in an almost Brechtian quality. I could see Cooper pulling the strings, and though I could discern his artistic objective and recognize its alternately grounded and operatic purpose, I seldom felt swept away by it. This is a film to be respected and admired, but I’m not sure I could love it.

Still, with qualified admiration, I acknowledge Cooper’s accomplishment, invoking a formal bravado that made me think of Orson Welles more than once. The dazzling camerawork feels experimental, as though Cooper has employed every technique he and cinematographer Matthew Libatique (who shot Cooper’s A Star is Born, 2018) could think of, similar to Welles’ approach to Citizen Kane (1941). Then there’s Cooper’s much-discussed fake nose prosthetic (some controversy follows this choice because Cooper isn’t Jewish, but it received approval from Berstein’s family), which reminded me that Welles often wore fake noses in his films. Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, Maestro’s opening quote implants a persistent enigma about his subject à la Charles Foster Kane, and it cannot help but invite comparisons between the two. However, the screenplay by Cooper and Josh Singer (Spotlight, The Post) doesn’t rely on a Rosebud key to answer questions about Berstein; it embraces a warts-and-all depiction, acknowledging that great art can spring from messy people.

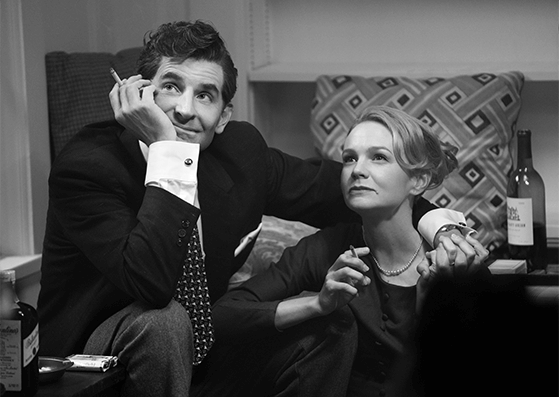

The film spans from 1943—when Berstein received his big break to conduct, without a rehearsal, the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall after the scheduled conductor became ill—to his last years (he died in 1990). At the outset, Libatique’s fluid camera movements, high-contrast monochrome images, and boxy Academy aspect ratio call attention to themselves. Occasionally, the story pulls us away from the showy presentation, such as when Berstein first meets Carey Mulligan’s Felicia Montealegre. Their courtship is charming and quick-witted, performed with the speed and humor of Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday (1940), often with forced vocal inflections by Cooper and Mulligan that feel distractingly artificial. But the characters share an authentic intimacy and humor in post-coital bedroom conversations or a tender moment in the park, sitting back-to-back, connecting in a profound way. She eventually proposes to Berstein, wistfully saying, “I know exactly who you are. Let’s give it a whirl.” And while Felicia seems uniquely capable of keeping up with Bernstein’s insatiable energy and drive to do it all, to say she knows him “exactly” is a misjudgment.

The film spans from 1943—when Berstein received his big break to conduct, without a rehearsal, the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall after the scheduled conductor became ill—to his last years (he died in 1990). At the outset, Libatique’s fluid camera movements, high-contrast monochrome images, and boxy Academy aspect ratio call attention to themselves. Occasionally, the story pulls us away from the showy presentation, such as when Berstein first meets Carey Mulligan’s Felicia Montealegre. Their courtship is charming and quick-witted, performed with the speed and humor of Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday (1940), often with forced vocal inflections by Cooper and Mulligan that feel distractingly artificial. But the characters share an authentic intimacy and humor in post-coital bedroom conversations or a tender moment in the park, sitting back-to-back, connecting in a profound way. She eventually proposes to Berstein, wistfully saying, “I know exactly who you are. Let’s give it a whirl.” And while Felicia seems uniquely capable of keeping up with Bernstein’s insatiable energy and drive to do it all, to say she knows him “exactly” is a misjudgment.

Between a creator and a presenter, a composer and a conductor, a loving husband and a man who increasingly identifies as gay, it’s not easy to pin down Bernstein. On top of his contradictions is his inestimable talent. How could Felicia hope to understand him when, at times, he doesn’t understand himself? Cooper acknowledges how Bernstein’s larger-than-life personality and talent loom large over Felicia in a beautifully rendered and expressive sequence, recalling the symbolic effect of the Broadway Ballet sequence from Singin’ in the Rain (1952). Whether it’s a dream or a vision, the incredible sequence uses Hollywood musical grammar, namely that of Bernstein’s Broadway musical On the Town, adapted to film by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen in 1949. Cooper shows Bernstein as a sailor dancing on stage with fellow sailors, and then Felicia is flung about among them. Eventually, they shuffle her away to watch the performance from just off stage. Later, the towering shadow of Bernstein dwarfs her faint presence in a similar shot. It’s not a subtle metaphor for their relationship, but it’s a gloriously realized one.

Once Maestro transitions to a lusciously saturated use of color when portraying the 1960s and 1970s, Bernstein’s contradictions lead to an unbridled ego, infidelities with men, and rampant drug use—that’s on top of his and Felicia’s incessant, distracting chain smoking. Felicia wants to keep his less convenient personality quirks contained and secret. Although she’s aware that her husband has had affairs with men, she insists that he not tell their teenage daughter (Maya Hawke) about his other life. Doubtless, this leads to Bernstein feeling further split between what he wants and what he does. “Man is a trapped animal,” he observes at one point. He’s trapped between teaching music on television and conducting others’ work, though he would prefer to be creating new music, such as West Side Story. He’s trapped by his society’s refusal to accept gay relationships, leading to fissures with a former lover (Matt Bomber) and Felicia. Though his sexuality is an open secret, he must maintain a so-called respectable public persona in these different times. But Felicia is more than a means to that end, even though it feels at times like he manages his family to facilitate his secret life, or that he wants to shake off his ties to explore his art.

Cooper’s filmmaking contains just as many contradictions as his subject. At times, Maestro is a remarkably accomplished film, but his facial prosthetics are occasionally inconsistent or don’t look quite right. The formal bravado is undeniable, but something about the two lead performances—their smoker’s voices, the Mid-Atlantic accents, the body language—registers as overblown and unnatural. Mulligan is at once assured and playing to the back row, like a performer in a 1940s movie. Maybe that’s the point, to underscore the degree to which Bernstein and Felicia led parallel lives, one for show, one authentic. If that’s the case, it’s a form-follows-function choice that sometimes neutralized my emotional involvement in the drama. Furthermore, it turns Maestro into more of a treatise than a straightforward narrative, which would also serve Cooper’s purpose. As I wrestle with the film, I can appreciate how Cooper wants us to confront Bernstein’s many layers, though I find it’s Cooper’s approach that I wrestled with more than Bernstein’s identity.

Cooper’s filmmaking contains just as many contradictions as his subject. At times, Maestro is a remarkably accomplished film, but his facial prosthetics are occasionally inconsistent or don’t look quite right. The formal bravado is undeniable, but something about the two lead performances—their smoker’s voices, the Mid-Atlantic accents, the body language—registers as overblown and unnatural. Mulligan is at once assured and playing to the back row, like a performer in a 1940s movie. Maybe that’s the point, to underscore the degree to which Bernstein and Felicia led parallel lives, one for show, one authentic. If that’s the case, it’s a form-follows-function choice that sometimes neutralized my emotional involvement in the drama. Furthermore, it turns Maestro into more of a treatise than a straightforward narrative, which would also serve Cooper’s purpose. As I wrestle with the film, I can appreciate how Cooper wants us to confront Bernstein’s many layers, though I find it’s Cooper’s approach that I wrestled with more than Bernstein’s identity.

One passage makes the viewer forget about all the superficiality and affectation. Cooper reportedly spent years learning how to conduct for a lengthy sequence set at the Ely Cathedral in 1973, when Bernstein led the London Symphony Orchestra in Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony No. 2. If every other scene didn’t boast such impressive visual attention, one might be tempted to say this sequence is the sole reason to see Maestro in the theater. It’s a magnificent few minutes, where the camera pans over the orchestra, vocal soloists, and Bernstein, who moves with an intensity that can only be described as an outpouring. He’s drenched in sweat, the curls in his hair flopping every which way, and his skin looks like fried chicken. Off in the distance, Felicia watches. Their relationship is at an all-time low at this point in the narrative, yet even she seems to forget about everything else for the sheer power of the moment. The sequence is a perfect distillation of itself within the film.

Maestro raises questions about Cooper’s intentions. What aspects does he mean to be at odds with each other? Which curious moments does he intend to feel incongruous to underscore the film’s central theme? A scene near the end finds Bernstein listening to R.E.M.’s “It’s The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” in the car. The audio blares the lyric “Leonard Bernstein!” a little louder than the other verses. Was Bernstein feeding his considerable self-image and blasting his name on the dial, or was Cooper overemphasizing the reference in a rather obvious way? The answer doesn’t matter, except that the filmmaker reflects his subject when he calls attention to his artistry. Cooper knows he has demonstrated spectacular skill, and he has effectively argued his thesis that Bernstein is a walking contradiction. But his conspicuous choices draw attention to themselves to sometimes disagreeable effect. Cooper ends the film with Bernstein asking an interviewer, “Any questions?” But the question, like so many aspects of the film, feels like Cooper reminding the audience of his presence, which hinders the connection between the viewer and Bernstein. Even as I ask these questions about Cooper’s intent, I recognize that the dissonance he creates is the point, so I must admire the result, though it nags at me in ways I don’t like. Maestro trapped me in an art-logic loop, which is a rare thing.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review