Labor Day

By Brian Eggert |

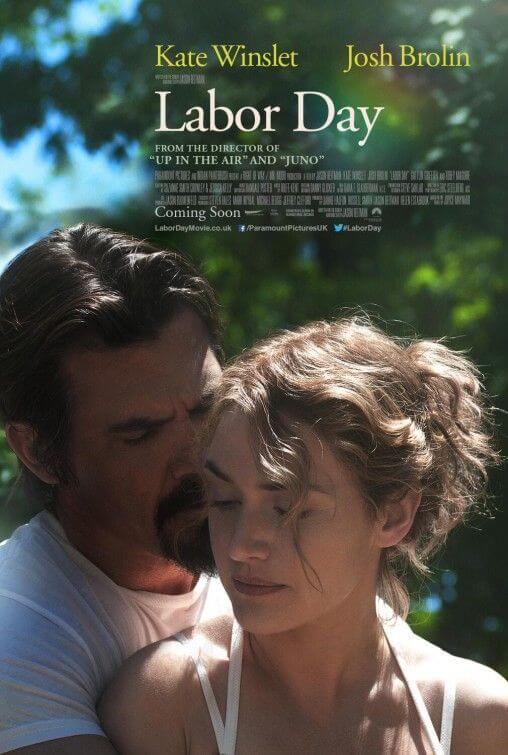

For Labor Day, Jason Reitman tests his not inconsiderable directorial talents in an adaptation of Joyce Maynard’s 2009 novel, a best-seller about a home invasion that transforms into a passionate love affair. Harlequin romance hasn’t been this pulpy since the Fabio heyday some two decades ago. The material represents a considerable shift for the writer-director, whose previous four films each settled in acerbic comedies. In 2005, Reitman made his feature debut with Thank You for Smoking, the dark satire about a tobacco lobbyist. He followed that with 2007’s breakthrough Juno and, for better or worse, made screenwriter Diablo Cody a household name. 2009 brought Up in the Air, a sobering and timely dramedy about America’s economic instability. Reitman reteamed with Cody for Young Adult in 2011 and tested his audience’s resolve for unlikeable characters. But none of his films have been as humorless, or as self-consciously serious as Labor Day.

Set over a hot holiday weekend in 1987, the story is told through voiceover by Tobey Maguire, the go-to voice for coming-of-age tales about young, socially awkward boys. About to enter the seventh grade, Henry (Gattlin Griffith) lives with his depressive and lonely divorcée mother, Adele (Kate Winslet), who has been abandoned by Henry’s father (Clark Gregg) for another woman. To the best of his ability, Henry tries to take care of his rattled mother; she’s all but incapacitated by the loss of love in her life and rarely leaves the house. In lieu of a man, he creates “Husband for a Day” coupons for his mother in a sweet (if Oedipal) gesture, rubbing her shoulders and taking her on a date to see D.A.R.Y.L. (which actually opened in 1985, but who’s checking). One day on a rare grocery store run, Henry and his mother meet Frank (Josh Brolin), an injured escaped convicted killer who jumped out of a hospital window during an emergency appendectomy. Bleeding and desperate, Frank presses Adele to drive him back to their home so he might hide out for a stint.

Within a few short hours, Frank’s otherwise gentle mannerisms lead to him winning over the lonely Adele and Henry. It begins when he makes them homemade chili and feeds the curiously receptive Adele. Police are on the lookout, and Frank must lie low. He ties Adele down, but only so she can say she was held against her will. Despite this, the next day, Frank earns Adele’s trust (and his handyman badge) by fixing loose floorboards, changing the oil on her station wagon, regrouting a stone wall, and cleaning out the gutters. (Note to fugitives on the lam: outside chores are not the best way to keep out of sight.) And though each of these chores could be used as an innuendo for the eventual romance that ensues, none is more obvious or unintentionally laughable than when he teaches Henry and Adele to make peach pie. He walks them through mixing the ingredients by hand and remarks, “Sometimes the best tool is attached to your own body.” As for the elephant in the room, the reason for Frank’s imprisonment and his side of the story are never discussed in detail with Adele, who altogether ignores the moral implications or parenting choices when she beds a killer-cum-kidnapper.

But then again, Frank promises there’s more to his story than the papers let on, and that he’s never intentionally harmed anyone. If only Adele could see the impressionistic flashbacks of Frank’s early life and the crime which landed him in prison. These scenes come out of nowhere and are confusingly relayed to the audience. Is Henry somehow showing us these scenes in his narration? How could he be? Despite Henry’s voiceover, sections of the story feel like they’re from Adele’s Stockholm syndrome-rattled mind, while the flashbacks could only be attributed to Frank’s perspective. As a result, Reitman’s various tones make for ungainly shifts in the dramatic perspective. Moreover, the film’s aesthetics suggest a much older setting than 1987 by at least ten years, as Reitman never quite convinces us of this romance’s time and place. The few indicators of the year are evident in nods to other movies, namely the posters for The Empire Strikes Back and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial in Henry’s room, and when Adele and Henry sit down with Frank to watch Close Encounters of the Third Kind on television.

Concentration should be placed on the two central actors, each performance is given under a layer of sweat and yearning sexuality. Winslet exudes the burden of being lovelorn in every carefully acted gesture, and perhaps her reputation for playing sexual beings in other films (Quills, Romance & Cigarettes, Little Children, etc.) enhances her sultry presence, though the material is certainly curbed for PG-13 consumption. Brolin carries a tender authority that makes him both mysterious and attractive. Conversely, Griffith seems inexpressive and miscast; it’s the kind of role which, ironically enough, someone like a younger Maguire would’ve been perfect for. Reitman’s ability to draw out fine performances remains intact, but his handling of sometimes solemn, sometimes tense, sometimes romantic material and its rather mushy roots doesn’t translate well to film. The cornier dialogue and the story’s leaps in plausibility for the sake of romance are the kinds of things a reader of pulp could be swept away by, but when they’re presented before you in a film, they become predictable, obvious, and far-fetched.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review