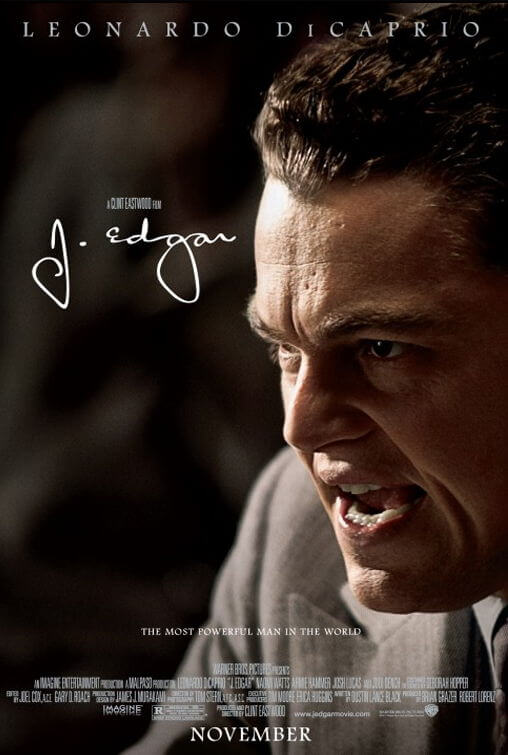

J. Edgar

Review by Brian Eggert | November 11, 2011

In their investigation into the life of John Edgar Hoover, director Clint Eastwood and Milk screenwriter Dustin Lance Black aren’t very thorough, and what decisive clues they do uncover feel like spoiled evidence. Their film J. Edgar stars Leonardo DiCaprio as the man who ran the FBI and its precursor, the Bureau of Investigation, for nearly forty years, from 1924 to his death in 1972. Hoover served under eight presidential administrations, using his “confidential” files as leverage to safeguard his position; he ushered in a new era of forensic science in criminal investigation; he led rigorous campaigns against Communists and Nazi spies in America; he supervised the men who captured John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson, and maintained that Bruno Hauptmann was solely responsible for the Lindbergh baby kidnapping. There were rumors, nothing confirmed, that Hoover was a homosexual and wore women’s clothes. But these are just bullet points on a timeline. The question remains: Who was J. Edgar Hoover?

Neither Eastwood nor Black seems to know. Their portrayal in this standard Hollywood biopic depicts Hoover as a reserved man of principles and fussy proclivities who housed an incredible amount of secrets, both political and personal. In a way, the structure recalls Citizen Kane, where the film looks back on a life to determine what drove its subject; except, there isn’t a crucial, character-defining object, like “Rosebud,” in Hoover’s life. The filmmakers do, however, make a strong case for Hoover’s lifelong companionship with FBI Associate Director Clyde Tolson (here played by The Social Network’s Armie Hammer), although this comes mostly as an afterthought. Hoover and Tolson dined and vacationed together regularly; when Hoover died, Tolson moved into Hoover’s home and inherited his estate. Onscreen, this relationship comes with a significant degree of understatement and reservation, and it did not drive Hoover’s life. Even if we’re meant to believe that Hoover and Tolson felt a deep bond for one another, but didn’t express it in physical terms, there are still so many secrets to Hoover’s life we must still consider. Eastwood and Black take the easy way out by attempting to define their mysterious subject by the one ounce of evident (yet speculative) humanity available to them.

Black employs a textbook biopic structure, where the aged subject looks back on his life. The story unfolds as Hoover’s various biographers listen to the man’s exaggerated accounts of his past deeds. Flashbacks and flashbacks-within-flashbacks explore Hoover’s attacks on “radicals” (but wash over his reluctance to attack organized crime), his conflict with the Kennedys, and his own opposition to Martin Luther King. DiCaprio plays Hoover as a man so dedicated and stubborn that he’s forsaken all social activities for his career. He lived with his authoritarian mother (Judi Dench) until her death; she shaped his narrow public view of homosexuals as “daffodils” who, along with women and African-Americans, he viewed with suspicion. His eccentric neatness defined his bureau’s G-Men, all of whom were required to wear well-tailored suits and shined shoes and no facial hair. His paranoia led to the storage of secret personal files and wiretaps. The film also delves into Hoover’s vanity, his desire for attention, and recognition of his achievements through publicity that falsely credited him for making arrests, like Dillinger’s.

As with Changeling, Eastwood works with production designer James J. Murakami to create impeccable details for the 1920s and 1930s backdrops. We feel transported to every era covered in the film, which spans several decades. Colors are saturated for a vintage photography look and costumes are gorgeously selected to give the period a heartbeat. Eastwood himself composed the unobtrusive music, and behind the camera, he delivers his usual low-key temperament as director, resulting in a slow pace for a 2-hour-and-17-minute film. Even still, the film leaves the viewer wanting more basic information. Given the attention put into such superficial elements, the narrative contains a surprising lack of historical details. Black concerns himself less with offering a biographical history lesson—despite Hoover’s remark in the opening that younger generations should know what happened and why—and more with making Hoover an emotionally impenetrable central character.

Though he’s receiving plenty of accolades for his performance, DiCaprio’s presence onscreen is undone by the film’s distractingly bad old-man makeup, and thus our inability to see anything but this charismatic young actor underneath a few inches of subpar movie magic. About half of DiCaprio’s screentime comes from behind a crusty, plastic-looking mask that relies on his voice to out-perform. DiCaprio’s performance is very similar to his brilliant, Oscar-deserving turn in The Aviator, which in every sense was more elaborate and defined and nuanced, whereas the subtlety behind DiCaprio’s performance here could be missed because of the makeup. Eastwood might have made a smarter move and cast an elder actor for the old-Hoover scenes, or perhaps a not-so-obviously attractive actor who could look plain. Hammer’s makeup is even worse, and unfortunately, he’s not one-fifth the actor DiCaprio is. Supporting players, like Naomi Watts as Hoover’s longtime secretary Helen Gandy and Josh Lucas as Charles Lindbergh, are quietly effective but not what one would call impressive. Dench is wonderful, as usual.

Perhaps looking at Citizen Kane more closely could have better shaped Black’s screenplay. With Welles’ film, we’re never watching from Kane’s perspective, rather the story comes from other perspectives as Kane’s character unfolds from various eyewitnesses. As the survey proceeds, the investigator remains baffled until the final frame shows Kane’s childhood sled, Rosebud, the thing which seems to define this complex personality. Imagine a different version of J. Edgar where the audience watches from the perception of others as they assess events in Hoover’s life. And then, in the end, we’re given a defining moment that informs the entire story, perhaps a final embrace of Tolson. That moment exists to an extent in Eastwood’s film, but not with the same degree of emotional revelation. Of course, it’s unfair to suggest that any film should aspire to be more like Citizen Kane, but nevertheless, it was a mistake on the part of Eastwood and Black to set the story from Hoover’s point of view, since the subject himself remains such an enduring mystery.

How can the filmmakers ever hope to truthfully and believably represent their protagonist if they don’t understand him, not really? By resolving that Hoover was a guarded man who harbored secrets and internalized his emotions, and refusing to speculate further, perhaps with a little potency, it feels as though Eastwood has resisted taking a stance on his subject. By the end, we don’t understand Hoover any more than we did when the film began. Along with the slow, intentional pacing, our failure to identify with this character undermines all of the other admirable elements in the film, including DiCaprio’s performance and the pitch-perfect production design. There’s simply no impetus behind what happens, nothing that makes a connection. This crucial mistake is what will distance audiences from connecting with J. Edgar as they might with a more fleshed-out biopic, which is surely what such an important historical figure deserved.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!