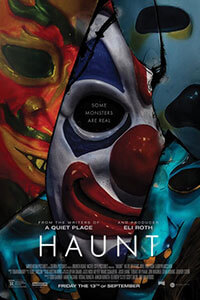

Haunt

By Brian Eggert |

“It’s Halloween,” one coed tells another. “Weird is good.” Weird can also be scary as hell, and the extreme haunted house in the 2019 slasher Haunt is run by some very weird people indeed. The movie is another entry in the horror subgenre of killer haunted houses. You know the drill: Some young adults explore spooky fun at a carnival or theme park, but fake scares give way to real ones when it turns out actual killers or even ghosts run the place. It’s not a new idea; the formula has been around for decades. What works so well about Haunt isn’t the three-dimensional characters or its particularly novel storytelling; it’s the scary quotient. Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, who penned A Quiet Place (2018), co-wrote and directed this movie with a sense of unnerving menace. The viewer feels like they’ve entered an intense haunted house that suddenly goes off the rails and becomes a real horror show, exploiting our suspicions, fears of haunted houses, and the people who operate them.

Haunt is the sort of movie that I almost don’t want to write about. Building too much expectation or trying to intellectualize a primal response could do your viewing a disservice. My entire review should be, “Do you like slasher movies? Then you should watch this. It’s scary.” Knowing this, I urge you to seek the movie out and return to this assessment afterward. For instance, when I saw Haunt, I knew almost nothing about it. After a limited theatrical window (which I missed), the movie appeared on Shudder. I read the brief synopsis and put it on, expecting something cheesy or mindless, but I found it scared the bejesus out of me. Sometimes that’s all a movie needs or wants to do. And the less you know about this one, the better your experience will be. Maybe that’s why people subject themselves to extreme haunted houses equipped with pages-long disclaimers promising to torment and test the limits of their participants with immersive, full-contact experiences. Not knowing the limits usually makes the proceedings scarier. People come away shaken, disturbed, and sometimes requiring professional help.

Who comes up with these effed-up haunted houses, you might wonder? Haunt answers that question with a nightmarish variation on established themes. Perhaps the best example is Tobe Hooper’s The Funhouse (1981), which features a horrifyingly mutated killer at a traveling carnival who hides under a rubber mask of Frankenstein’s monster. Rob Zombie delivered his take in House of 1,000 Corpses (2003), featuring a roadside attraction operated by a family of psychopaths straight out of Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). More recently, 2018’s underrated Hell Fest featured a likable bunch of twentysomethings at a horror theme park, stalked by a masked killer who uses the park’s décor to cover his murderous nocturnal hobby. However, those expecting the same level of fun and dark humor supplied by Haunt’s antecedents may be disappointed. At the very least, it proves superior to cheapies like Dark Ride (2006), The Houses October Built (2014) and its 2017 sequel, and the found-footage series Hell House LLC (2016).

Beck and Woods set the dreadful mood with a few nondescript shots of someone drilling, pounding hot metal, setting tripwires, and printing haunted house fliers that look like ransom notes. Clearly, the managers of this establishment have something intense planned. Then, Haunt takes a familiar look down an autumnal Illinois street on Halloween night, like something out of John Carpenter’s 1978 classic. We meet a few college students who live in campus housing, centered around the fragile Harper (Katie Stevens), who breaks up with her abusive boyfriend via text at the insistence of her friend. Afterward, she has the nagging suspicion that someone is following her. That evening, dressed in costumes and ready for anything, Harper and five others find a flier for an out-of-the-way haunted house. Being invincible and impulsive, they drive to the location, where they’re greeted by a speechless attendant in a clown mask.

Beck and Woods set the dreadful mood with a few nondescript shots of someone drilling, pounding hot metal, setting tripwires, and printing haunted house fliers that look like ransom notes. Clearly, the managers of this establishment have something intense planned. Then, Haunt takes a familiar look down an autumnal Illinois street on Halloween night, like something out of John Carpenter’s 1978 classic. We meet a few college students who live in campus housing, centered around the fragile Harper (Katie Stevens), who breaks up with her abusive boyfriend via text at the insistence of her friend. Afterward, she has the nagging suspicion that someone is following her. That evening, dressed in costumes and ready for anything, Harper and five others find a flier for an out-of-the-way haunted house. Being invincible and impulsive, they drive to the location, where they’re greeted by a speechless attendant in a clown mask.

Long before the characters enter and discover they’re trapped in an actual death maze, Haunt sets its mood through slow, creepy imagery. The haunted house itself, a well-designed series of rooms, coffins, and narrow passageways, looks like something you’d experience in a real haunted attraction. Harper and her friends move through the labyrinth at a measured pace, washed by brightly colored light, and when they encounter one of the many masked figures inside, the interaction uses an eerily patient series of movements. You can feel the violence coming, and when it does, the displays are brutal and almost unbelievable at first. Beck and Woods gradually ratchet the tension up, allowing the viewer to question whether the operators of this haunted house have employed elaborate smoke and mirrors or if they’re actually killing people. More than halfway through the movie, we realize it’s real. The violence is shown in graphic and pounding detail, and it comes with a disturbing revelation.

One of the most effective aspects of Haunt is how the filmmakers reveal the killers. Initially, the haunted house’s workers don costumes with plastic masks in the shape of a clown, devil, witch, and ghost. Masks hide the person underneath—the person inside—and create a representational false front. Sometimes, the people underneath look normal enough, and the mask allows the wearer to become someone else. Beck and Woods create characters who, when they peel off their mask to show their true faces, reveal actual monstrosity. Body modifications, implants, and tattoos have twisted and ornamented the flesh to turn each killer’s face into a surgical approximation of a clown, devil, witch, and ghost. They’re truly les bêtes humaines, inside and out, and their willingness to externalize their inner selves in such disturbing ways elevates how frightened they should make us. Although each of them is only human, they represent the limits of human depravity.

The sheer terror that accompanies these figures presents a decidedly more dramatic conflict for Harper to overcome. A few flashbacks to Harper’s childhood suggest a pattern of abusive men in her life, starting with her father and extending to her recent ex-boyfriend (who eventually stalks her to the haunted house). Her current predicament gives her a chance to fight back, to stop hiding under the bed and face her abusers. It’s an obvious character arc, but by the final frames when she has reclaimed her agency, we’re happy to see her emerge into the heroic “final girl” trope. (Note: If any pattern can be drawn between A Quiet Place and Haunt, it’s that Beck and Woods clearly have a thing for a woman wielding a shotgun as a final image.) And while her character harkens back to Laurie Strode or countless other final girls, her eventual victory feels earned, if only because the movie’s killers prove so singularly fearsome.

The sheer terror that accompanies these figures presents a decidedly more dramatic conflict for Harper to overcome. A few flashbacks to Harper’s childhood suggest a pattern of abusive men in her life, starting with her father and extending to her recent ex-boyfriend (who eventually stalks her to the haunted house). Her current predicament gives her a chance to fight back, to stop hiding under the bed and face her abusers. It’s an obvious character arc, but by the final frames when she has reclaimed her agency, we’re happy to see her emerge into the heroic “final girl” trope. (Note: If any pattern can be drawn between A Quiet Place and Haunt, it’s that Beck and Woods clearly have a thing for a woman wielding a shotgun as a final image.) And while her character harkens back to Laurie Strode or countless other final girls, her eventual victory feels earned, if only because the movie’s killers prove so singularly fearsome.

That said, fear is irrational. It’s a product of our lizard brains. There’s no telling what will scare you, and it’s sometimes difficult to explain why a scary movie affects you the way it does. Although I’ve seen plenty of horror movies with similar plotting and more compelling characters, few slashers have disturbed me, and continue to disturb me, as much as Haunt. It stayed with me enough to want to write about it two years later. Even on a recent second viewing, I had the same potent reaction. It’s not about shocks or jump-scares, although the movie does have a few good ones. Instead, it’s about dreading the vile limits of humanity, and then seeing those limits made flesh in self-articulated human monsters. People are scary enough without the aid of augmentations. With them, they’re downright terrifying.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review