Frankenstein

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on October 12, 2025, from the MSP Film Society’s Cine Latino Film Festival.

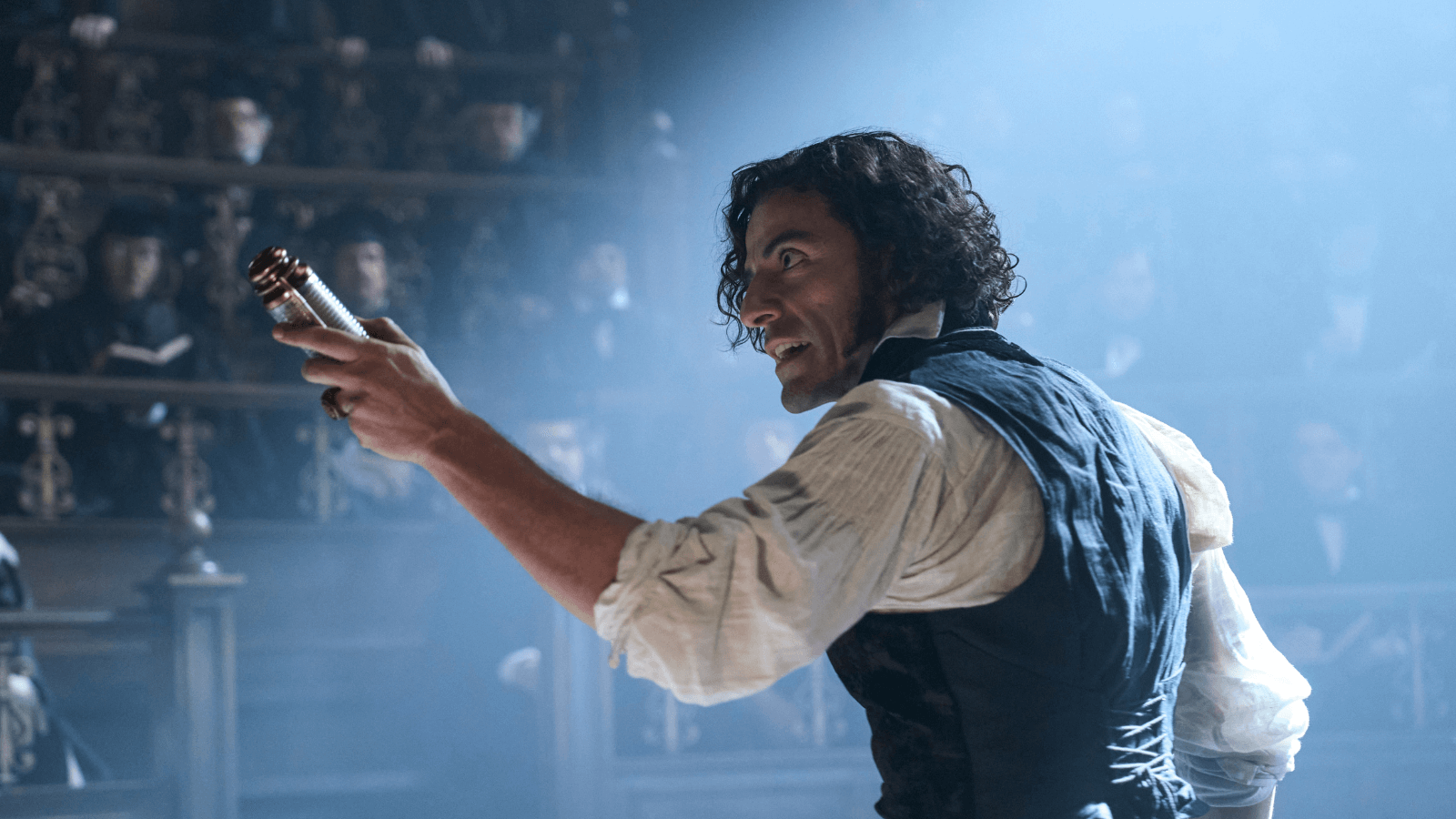

Gothic tales of misunderstood monsters have permeated Guillermo del Toro’s cinema since his earliest efforts, so it’s fitting that the Mexican dreamer, fabulist, and visionary finally adapts Mary Shelley’s 1818 horror novel, Frankenstein. At once classical and revisionist, del Toro’s version might be the truest to the source material of all the many screen adaptations, not only in terms of what happens, but also for its essential questions about what makes someone human and what makes them a monster. Whereas James Whale, Hammer Films, Kenneth Branagh, and dozens of others have only just tapped the emotional core of Shelley’s text, preferring to dwell on its frightening or obsessional aspects, del Toro approaches the book with sensitivity and humanity. He also spares nothing as a showman, delivering a lavish production shot with the fastidious, macabre details and sublime beauty that harmonize with his operatic treatment. Teeming with expressive performances by Oscar Isaac and Jacob Elordi and a theatrical grandiosity that underscores its themes, Frankenstein finds del Toro capturing the romantic tragedy of Shelley’s timeless story as never before.

The film marks the third in del Toro’s recent streak of renewed literary adaptations, beginning with his triumphant and underrated Nightmare Alley (2021), a cynical noir that explored the director’s authorial preoccupations without his usual fantasist touches. He followed that with a much-lauded animated version of Pinocchio (2022), rendered in gorgeous stop-motion work that, for me, did not surmount the familiarity of the material. Del Toro doesn’t have that problem with Frankenstein, given that his filmography seems to have built up to this moment. What are his Hellboy movies, The Devil’s Backbone (2001), Crimson Peak (2015), and multiple-Oscar-winning The Shape of Water (2017) but evocations of a Gothic atmosphere and Shelley’s sympathy for the misunderstood monster? Even with the filmmaker’s well-established interest in Shelley’s book, his $120-million production for Netflix—thanks to the thoughtful writing, the terrific performances, and the opulent production values—reanimates this version of the modern Prometheus with a bolt of lightning.

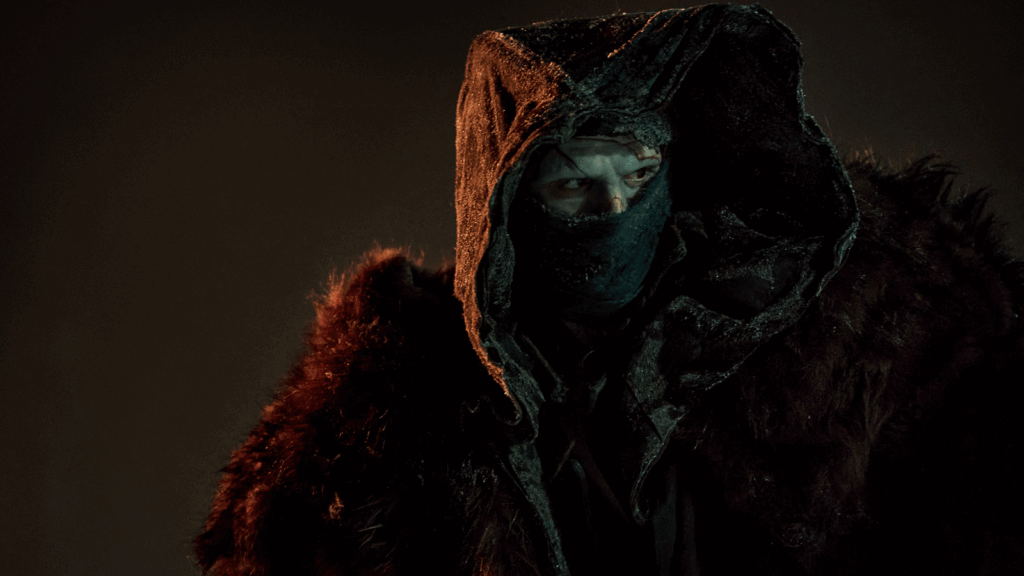

Similar to the book, del Toro’s narrative unfolds in the Arctic, where Danish explorers caught in the ice encounter a desperate man, Victor Frankenstein (Isaac), pursued by a roaring, unruly figure in shrouds (Elordi). The year is 1857, and the Danish sailors open fire on the mysterious abomination, who tosses and tears them apart in pursuit of his maker. Frankenstein, after the sailors rescue him from the cold, tells his account to their crew’s commander, Captain Anderson (Lars Mikkelsen). Del Toro arranges the story in two parts, Victor’s Tale and The Creature’s Tale, offering the mad scientist’s view of what happened before reframing his perspective after the Creature arrives on the scene. Given the film’s two perspectives, del Toro employs a novelistic variation in tones, alternating between the romance of discovery, the horror of creation, and the tragedy of self-awareness, which may prove jarring to viewers who prefer their films more tonally straightforward. The Creature later remarks, “I am obscene to you. But to myself, I simply am.” It’s a line that encourages viewers to embrace what they see in all its varied moods.

A Freudian take on Shelley’s novel, del Toro’s script introduces an Oedipal version of Victor, whose inseparable, clingy affection for his short-lived mother (Mia Goth) as a child transfers in adulthood to Elizabeth (also Goth), the fiancée of his younger and less manic brother William (Felix Kammerer). The young Victor (Christian Convery) also despises his scornful father (Charles Dance), who teaches the boy all the wrong lessons about parenting. When Victor gets an anatomy question wrong, his renowned surgeon father resolves to punish not with a thwap on the hands—those are a surgeon’s tools, after all—but across the face. The lessons Victor takes into adulthood about parenting from these formative interactions permeate his subsequent relationship with the Creature. When Victor makes life, he does so out of selfish scientific ambition, and when he succeeds, he proves incapable of genuine parental love. Discarded and unloved, what other choice does the Creature have except to become the monster Victor perceives him to be?

With his mother’s sudden passing prompting his adolescent desire to “conquer death,” the adult Victor becomes a radical scientist whose theories about, and chilling demonstration of, reanimated corpses using electricity scandalize the Edinburgh medical community. Victor captures the attention of a wealthy arms manufacturer, Henrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz), who—like billionaires today with their blood boys and biohacks—hopes to find a cure to mortality. Setting up inside an isolated tower that recalls the structure in Crimson Peak, both in its dilapidation and ornamentation, Victor proceeds to build the elaborate engine that will fuel his new life. At the same time, he falls for Elizabeth, the sole voice who challenges Victor’s plan by laying bare the dangers of pursuing ideas at any human cost. Regardless, Victor assembles his creation from the corpses of dead criminals and soldiers, not by sewing pieces together to compile the stitched-up, green-skinned clod of previous iterations, but by constructing it from the inside out into an eerily smooth and patchy gray figure reminiscent of the Engineers from Prometheus (2012).

While Isaac lends his Frankenstein a marvelously demented zeal that twists and contorts into a reflection of his abusive father, Elordi plays the Creature with an almost silent movie performance; his sleek, towering body moves in gestures that look like an avant-garde dancer and invite us to lean in to understand the character. Still, the Creature’s seeming lack of intelligence (he says only one word at first: “Victor”) frustrates his impatient father, who keeps his experiment chained in a drainage room, where he beats and berates the poor, unfortunate soul. Only Elizabeth, who’s fascinated by insects and searches with empathy for the tenderness in all living things, sees the intelligence behind the Creature’s eyes. Victor attempts to terminate his experiment, but it’s nigh-invulnerable, prompting a hunt worthy of another literary obsessive, Ahab. However, when the story shifts to the Creature, the would-be fiend shares a moving account of his education and friendship with a blind man (David Bradley)—a true “friend”—along with his inevitable desire for a companion.

To no one’s surprise, Frankenstein is a breathtaking production, designed with sumptuous detail by Tamara Deverell, costumed by Kate Hawley in darkly ornate fashions, and set to an evocative score by Alexandre Desplat. Most refreshing is del Toro’s insistence on building actual sets so his actors have vast spaces to inhabit, as opposed to green screen voids. This is not to suggest the film is without CGI, and when it’s used, it’s usually to a distracting effect. For instance, Victor has several dreams about a fiery red angel compelling his mission, while later, the Creature encounters a pack of wolves—and neither of these VFX looks particularly good. Most of the backgrounds and skies have a digital sheen to them as well, adding a heightened quality to the sun and clouds. However, del Toro and his frequent cinematographer since Mimic (1996), Dan Lausten, aren’t aiming for realism here; this is a larger-than-life story manifested in the theatrical, exaggerated mode of Gothic horror and even German Expressionism, where intense emotions find their counterparts in the baroque locations, performances, and flourishes.

Who better than del Toro to find sympathy for a monster? As a child, he was moved by an early screening of Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), and again by the humanity given to the Creature in Víctor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive (1973). After so many versions of this story that dwell on the monstrous aspects, including Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and other offerings, or even those that attempt to give the Creature dimension, such as Branagh’s zippy Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), most feel surface-level at best. As a filmmaker, del Toro understands the fervent desire to create life, yet he also has boundless sympathy for his characters, particularly outsiders. The few brief scenes where Elizabeth (played with tenderness by Goth, inhabiting a role perhaps better suited for Mia Wasikowska) connects with the Creature imbue Victor’s creation with a selfhood that might have been unachievable otherwise. Most affecting is del Toro’s wounded portrait of the trauma inherited by sons from their fathers—how Victor’s father passes down his violence to his son, and the Creature learns those same lessons, later beating Victor and shouting with aching desperation, “You only listen when I hurt you!”

Del Toro views Frankenstein as a story that transcends the tale of a man who creates life from death; it’s also about every parent being a creator who shapes their child through upbringing and the lessons they share. The filmmaker ends his two-and-a-half-hour epic with a quote from Lord Byron: “And thus the heart will break and yet brokenly live on.” The quote underscores the filmmaker’s emotional intent with Frankenstein, where his adaptation’s substantive dramatic choices outweigh, or rather are complemented by, his otherwise sensationalist production and visual treatment. Instead of merely experiencing these characters and situations for the umpteenth time, with a passive acknowledgment of how del Toro has varied and built upon Shelley’s themes, the viewer watches as though witnessing the story unfold for the first time. Unlike his Pinocchio, del Toro’s Frankenstein revives these characters for a version that may never overtake the iconography of what Whale and Boris Karloff created in the 1930s, but it locates the soul of this dark tale as no other adaptation has.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review