Foe

2.5 Stars- Director

- Garth Davis

- Cast

- Saoirse Ronan, Paul Mescal, Aaron Pierre

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 110 min.

- Release Date

- 10/06/2023

Note: Garth Davis’ Foe is currently in limited theatrical release and screens at the Twin Cities Film Festival on Monday, October 23, 2023. It arrives on Amazon Prime Video soon.

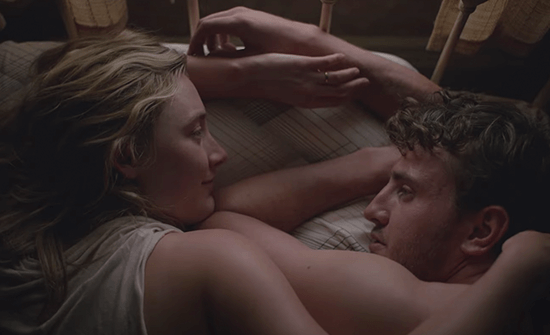

Novelist Iain Reid’s debut novel supplied writer-director Charlie Kaufman with the raw material to make I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020), a mindbender that uses its bizarre structure and cryptic imagery to explore a character’s mind. The author’s 2018 follow-up, Foe, does something similar for Garth Davis, the filmmaker who wrote the adapted screenplay with Reid. The material’s sci-fi conceit launches a complex examination of a relationship, but similar to Reid’s first work of fiction, it’s less about a relationship than an individual who feels that their marriage has lost its luster and become repetitive, confining, and lifeless. The problem is the manner in which the plot unfolds does the material no favors and even robs the narrative of its emotional power. This is a shame, since stars Saoirse Ronan and Paul Mescal give tour de force performances in scenes where the viewer isn’t quite sure of the exact context, which, symbolically, represents the off-kilter emotional circumstances revealed late in the film. To be sure, Foe is more concerned with setting up elaborate twists than engaging in the true feelings of a given scene, making it better appreciated on a second viewing, perhaps. But who has the time and energy for that?

Set in “The Midwest, 2065,” the film opens with titles about Earth’s natural resources dwindling and artificial people known as “human substitutes” being created to help. Inside an old farmhouse, Ronan’s Hen, short for Henrietta, and her husband Junior (Mescal) receive a strange visit at night from Terrence (Aaron Pierre). An employee of Outermore, a governmental outfit building a space station to give humans a new place to live, Terrence announces that Junior is on a waitlist to work in the orbiting station. He could be on the waitlist for years, but the initiative is lucrative and designed to help future generations. Junior has no choice, either; his conscription is tantamount to a wartime draft. And while Junior waits for the process to begin, he and Hen live out their lives on a barren landscape devoid of rain and other people. He works at an industrial turkey farm; she toils at a throwback diner. They spend their days drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon, listening to twentieth-century oldies (cue Skeeter Davis’ on-the-nose “It’s the End of the World”), and inhabiting Junior’s fifth-generation family home. Although they’re high-school sweethearts, Hen behaves as though she’s trapped and uneasy with her husband, while Junior seems lost and searching.

Before we can determine what’s off about their marriage, a year passes, and Terrence arrives with some news. Junior will begin assessments for space work, assuring the company that he’s up for the mental and physical challenge. The two-hander chamber drama becomes a three-hander with Terrence in the mix, pushing Junior and Hen to their limits. Terrence explains that the company wants to ensure Hen isn’t alone for a prolonged period, so they plan to substitute Junior with one of their identical biological replicants. If you’re a Black Mirror viewer, a similar idea is explored in this year’s season six episode, “Beyond the Sea,” albeit to superior effect, and without credit to Reid’s story. Chalk it up to synchronicity, I suppose, that two stories released in the same year involve a double left with a wife to replace her astronaut husband. That 80-minute episode offers more by way of plotting and chilling developments, whereas Foe has a thornier setup with an intentional lack of clarity—the sort that makes you lean forward to piece it together.

When they’re alone, Hen and Junior have a push-and-pull quality. In the early scenes, she cries alone in the shower or sneaks down to the basement to play piano, which Junior hates. However, Terrence’s presence inside of this failing marriage remains confusing. Recalling scenes from Blade Runner (1982), he conducts physical exams of Junior and asks him deeply personal questions, mining the depths of his psyche in order to build a convincing replacement for Hen. Though, the country boy buckles with anger like a prodded bull, with Mescal writhing in anguish and punching walls, forcing us to wonder: Why does this company want this guy in their space program? Why are they dedicating so many resources to one employee? Terrence becomes quite personal with the couple, bringing them French wine and telling Junior what Hen will need when he’s away. Moreover, it seems unlikely that Terrence would be able to build an AI counterpart for Junior just by asking questions. Shouldn’t he do a brain scan or something? How will they build Junior’s subconscious? Won’t the information passed to Terrence break down like a game of telephone as he passes that information along, thus rendering an inaccurate version of Junior?

When they’re alone, Hen and Junior have a push-and-pull quality. In the early scenes, she cries alone in the shower or sneaks down to the basement to play piano, which Junior hates. However, Terrence’s presence inside of this failing marriage remains confusing. Recalling scenes from Blade Runner (1982), he conducts physical exams of Junior and asks him deeply personal questions, mining the depths of his psyche in order to build a convincing replacement for Hen. Though, the country boy buckles with anger like a prodded bull, with Mescal writhing in anguish and punching walls, forcing us to wonder: Why does this company want this guy in their space program? Why are they dedicating so many resources to one employee? Terrence becomes quite personal with the couple, bringing them French wine and telling Junior what Hen will need when he’s away. Moreover, it seems unlikely that Terrence would be able to build an AI counterpart for Junior just by asking questions. Shouldn’t he do a brain scan or something? How will they build Junior’s subconscious? Won’t the information passed to Terrence break down like a game of telephone as he passes that information along, thus rendering an inaccurate version of Junior?

These questions, inspired by better sci-fi movies and literature about artificial intelligence, receive only unsatisfying answers in Foe. When the film reveals its secrets, it’s chilly, frightening, and disorienting, forcing the viewer to reconsider everything we’ve seen. But it doesn’t all come together from a genre perspective, leaving us with more questions the film cannot answer. Davis and Reid show more interest in using the situation to diagnose a marriage and chart how Hen feels removed from it, which is fine, until the story mechanics get in the way of that drama. Even so, this is often a beautiful and entrancing, if slow-moving, film with scenes where cinematographer Mátyás Erdély shoots lyrical imagery reminiscent of Terrence Malick (what is quickly becoming a cliché shorthand for profundity), filmed at magic hour with a curious, observant lens. Shot in Australia, the film’s dusty wasteland setting creates a sharp juxtaposition with the purple and orange skies, anchored by the ponderous score (by Oliver Coates, Park Jiha, and Agnes Obel) and Peter Sciberras’ impressionistic editing, which adds to the occasional feeling that the world presented is askew.

After it’s over, you might look back and appreciate what you’ve seen and how intricate the performances are, especially Ronan’s fierce and trapped Hen—whose name is another pointed metaphor, considering where Junior works. Given the nature of the story, some of that may be missed in the moment as you try to figure out what’s happening and why. As a result, Foe plays a cruel trick on the viewer by not telling the story in a more straightforward manner, if only so we can identify with the characters and appreciate the nature of the performances as they occur. The choice might make more sense in a novel, where the author aids the reader’s mind to piece together how a scene looks and feels. The immediacy of cinema doesn’t give the viewer that luxury, and the actors’ faces and body language communicate in ways that must be interpreted, not envisaged. And yet, while it’s frustrating that the film is overdependent on its structural puzzle, it’s easy to appreciate how Ronan and Mescal set the screen ablaze.

Predator

Predator  Never Let Me Go

Never Let Me Go  Attack the Block

Attack the Block