Close Your Eyes

By Brian Eggert |

Víctor Erice’s Close Your Eyes opens and closes with segments from a fictional unfinished film called The Farewell Gaze. Set in 1947 on the outskirts of Paris, the film’s prologue sequence unfolds on the estate of Mr. Levy (Josep Maria Pou), a wealthy man who enlists a friend (José Coronado) to visit Shanghai and locate his estranged daughter. Tired of disingenuous sycophants, Levy wants to look into his daughter Judith’s eyes one last time and feel her unique gaze. This film-within-the-film was never completed; only the scenes at Levy’s home, where the narrative starts and resolves later. The film’s lead actor vanished in 1990, and nothing else was completed. Just as a mysterious disappearance and search propels The Farewell Gaze, similar action moves Close Your Eyes, a loving ode to cinema’s transportive ability to find answers, call forth memories, and supply resolutions with transformative power. Embracing an intertextuality to thoughtfully explore the parallels between his narrative and his nested film, his passion for filmmaking, and even various works in his career, Erice has delivered a film that miraculously avoids sentimentality or preciousness about cinema even while celebrating its capacity to impact its devotees in profound ways.

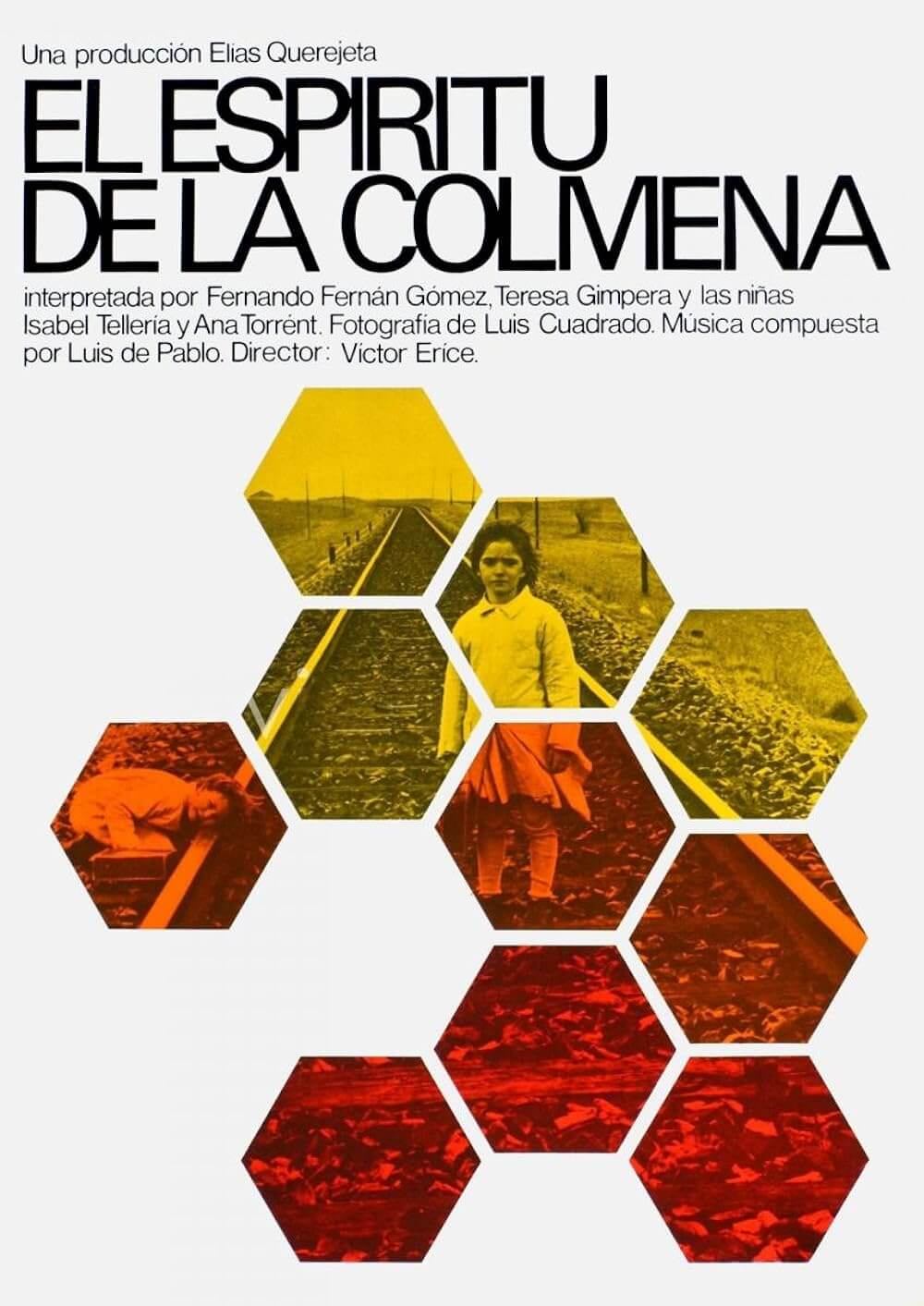

Erice has directed only four features in 50 years. The filmmaker’s debut in 1973 with The Spirit of the Beehive is often hailed as one of the finest pictures ever made, in Spain or anywhere else. A haunting tale entwined in Spain’s traumatic past and cinema, his freshman effort involves the 11-year-old Ana (Ana Torrent), who becomes fixated after seeing James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) in her small Castilian village in 1940, just after Francisco Franco took power following the Spanish Civil War. With an active imagination and equal parts fear and curiosity, Ana searches for the titular spirit, the intangible form of Frankenstein’s monster that reflects her complex world yet is articulated best by cinematic imagery. It would be another decade before he released his second feature, El Sur (1983), another aching drama set after the Civil War and also about a young girl, this one shaken by the discovery that her mystical father was in love with a movie star. Although Erice never completed the last part of El Sur, the otherwise complete feature-length result weighs cinema’s potential to change lives. Erice also made a documentary portrait of an artist with 1992’s The Quince Tree Sun (aka Dream of Light) and several short films.

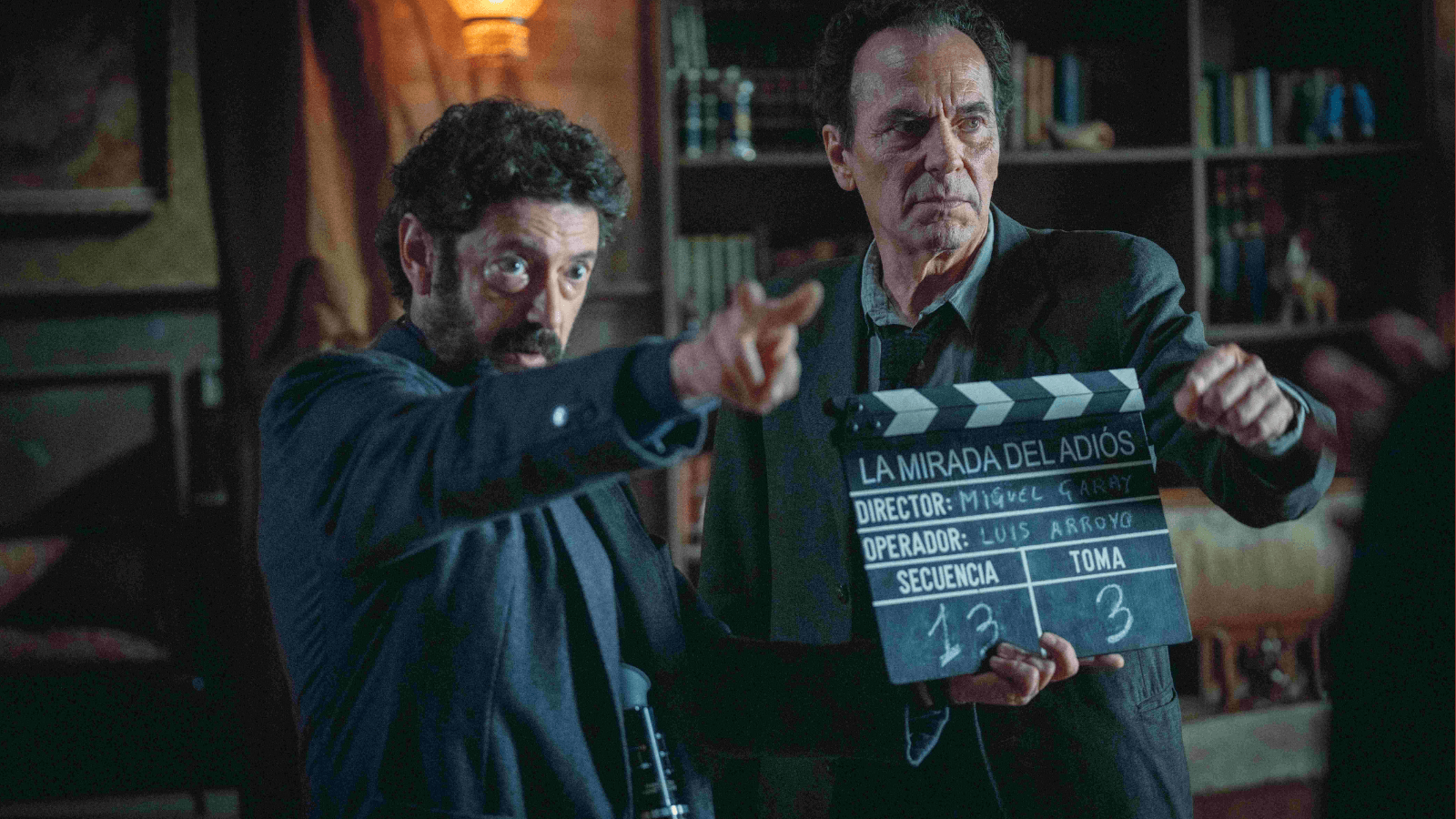

Although his oeuvre is limited, the 84-year-old filmmaker’s passion for cinema remains central. Close Your Eyes functions like a natural extension of his output to this point, and it’s easily his most self-reflective film to date. Manolo Solo plays a former director named Miguel Garay, who retired from moviemaking in 1990 following the cancellation of work on The Farewell Gaze. The production shut down when his star, Miguel’s longtime friend Julio Arenas (Coronado), disappeared without a trace and was presumed dead. Given Julio’s penchant for drinking, womanizing, and depression, some think he may have committed suicide; others believe it may have been a freak unexplained accident. Miguel’s long-dormant questions about what happened to Julio reemerge in 2012 when a Madrid-based television show called Unresolved Cases decides to showcase the missing actor’s story. Miguel reluctantly agrees to be interviewed, which puts him in a reflective state, inciting an intentionally paced pseudo-detective story that carries out over the film’s nearly three-hour runtime.

While the thrust of the narrative involves Miguel’s search for answers, Close Your Eyes takes a circuitous path to find them. This allows Erice to indulge in thoughtful and entertaining asides. While still in Madrid, Miguel visits an old friend and former editor, Max (Mario Pardo), who maintains a collection of films on celluloid. They watch the remaining footage from The Farewell Gaze and lament the digitization of films and streaming, since newer formats lack the tangible quality that makes them so inextricable from our experience. Thirty or forty years from now, after Netflix and other streaming services have gone under, there will be no warehouses or storage facilities to locate lost digital-only films, apart from corruptible servers and hard drives. They will have no place in the cultural memory. And while celluloid, too, can degrade beyond repair, restoring and archiving remains central to cinema’s history and reinforces the lasting influence of film art. Close Your Eyes might even be a metaphor for the importance of film preservation and the detective work involved.

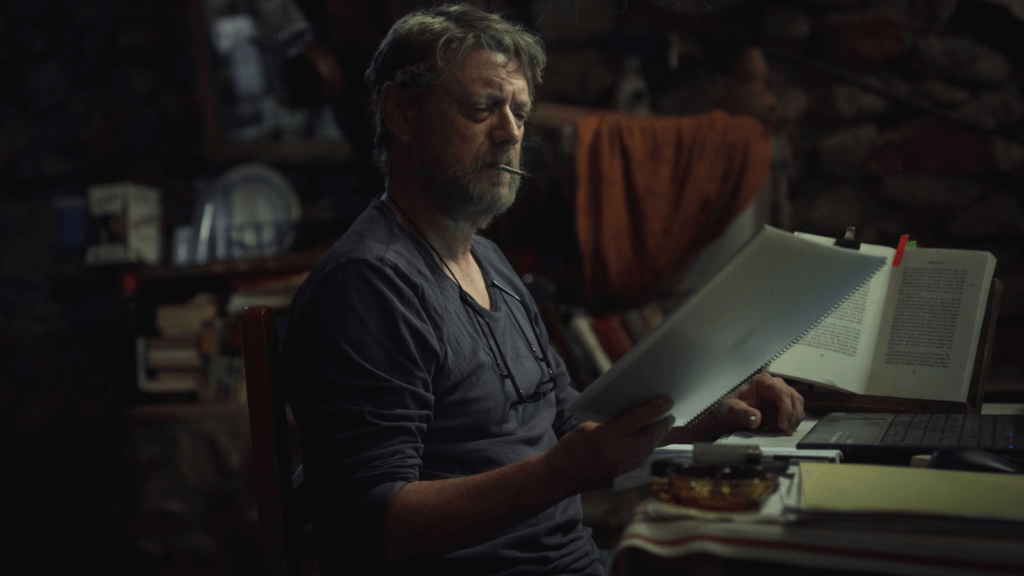

Another sequence takes place near Miguel’s home. He lives in a ramshackle trailer near the sea on a fenced-in plot of land—a makeshift village where he spends his time fishing and tinkering with some film-related writing projects. There, he has a dog named Kali and close ties with his neighbors. One night, Miguel performs “My Rifle, My Pony and Me,” originally sung by Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson in Rio Bravo (1959), resulting in a tender moment with a gentle melody about fellowship, a major theme in Erice’ film. The friendship between Miguel and Julio lives in the director, and he imagines Julio’s last moments in a mental projection—a kind of short film that plays out in the director’s head, although it was never made and is purely speculative. Close Your Eyes becomes a testament to the bonds that film workers make on productions, spending months together, all focused on the same creative pursuit. Miguel’s lasting friendship with Julio and the actor’s subsequent disappearance have scarred him, so when he receives a call that Julio might be in an asylum, the possibility is unthinkable. When Miguel confirms it’s him, albeit stricken with retrograde amnesia, the filmmaker feels an overwhelming sense of hope.

Viewers unfamiliar with Erice’s work need not explore his short filmography to understand Close Your Eyes. Still, it’s an even more immersive and moving experience for those who can make the connections between, say, the unfinished El Sur and The Farewell Gaze. With Miguel an apparent counterpart for Erice and played in a tremendous performance by Solo, the film is a self-reflective look at unfinished projects and open wounds, often with allusive connections to his earlier films. Note how Ana Torrent, the child star of The Spirit of the Beehive, plays Julio’s daughter, also named Ana. Her character works at the Prado Museum and laments her father’s absence from both her childhood and adulthood. Solo and Torrent convey lifetimes of experience, regret, and unanswered questions in their eyes, giving unflashy but exceptionally emotional performances. When Ana is finally confronted with her father again, it’s as though a specter from the past has returned—a ghost or even a kind of monster. How appropriate, then, that she reintroduces herself to her father with the final haunting, trancelike line from Erice’s 1973 masterpiece: “I’m Ana.” Even the title of the director’s new film may link to El Sur, where the diviner father performs his routine: “Close your eyes,” he says, “and let your mind go blank.”

Erice romanticizes cinema, supplying a testament to its mesmeric effect—if the viewer is willing to submit to the experience. Close Your Eyes may have a lengthy runtime and almost no score to accompany the film’s quiet enchantment, save for Federico Jusid’s delicate piano. But its long passages of silence and patient rhythm ensnare the audience as only cinema can. Whereas other “love letter to cinema” movies tend to overemphasize the point with obvious statements, Erice demonstrates why he loves movie by allowing his filmmaking, not the dialogue, to do the work. It’s no coincidence that Miguel and Max grumble about the state of digital technology over photochemical processes. Erice employs cinematographer Valentín Álvarez’s crisp digital photography for all except scenes shot for The Farewell Gaze; those were shot on celluloid. Erice underscores the film’s sense of the past and present by demonstrating through the course of Close Your Eyes that, yes, while digital filmmaking supplies a similar result in a different format, celluloid has a preferable tangible quality. Physical objects that conjure memories play a central role in the film, prompting Miguel to remember his past and in turn use those objects to bring Julio’s memory back—the photo of Miguel and Julio as young sailors, the sailor’s knots Miguel tests with Julio, The Farewell Gaze on celluloid, and the setting of a moviehouse have an uncanny potential to produce specific memories through sensory associations. Does digital cinema have that same ability? For some, perhaps not, and this adds to the film’s notion of loss through time in the so-called advancement of filmmaking formats.

With its connections to the director’s earlier work and life, Close Your Eyes is a brilliant achievement that plays like the summa of Erice’s career, which has always ruminated on cinema as the nexus where art, identity, and memory converge. Cinema remains the starting point from which Erice engages with all other aspects of life. For Miguel and Julio, cinema becomes a vessel through which they access memories and remember who they were decades ago, and how those factors continue to shape who they are. Erice has spent his life appreciating cinema and, like many of us, using its boundless potential for expression and empathy to understand the world and ourselves better. Close Your Eyes suggests that life’s mission, the search for self-understanding, is achieved through a combination of cinematic modes and real-life experience, the tangible and ephemeral. In Erice’s conceptual worldview, which is never entirely sentimental but lovingly articulated nonetheless, the two work together, complementing and informing each other throughout a lifetime of encounters, both onscreen and in reality.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review