Blue Moon

By Brian Eggert |

Blue Moon takes place on the evening of March 31, 1943. Oklahoma! has just had its Broadway premiere, and the cast and crew will gather at Sardi’s, a popular theater district nightspot where they will await the reviews. The musical marks the first collaboration between the famed duo of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II (Andrew Scott, Simon Delaney). Rodgers’ former writing partner, Lorenz Hart, played by Ethan Hawke, attended the show at the St. James Theatre and found it ridiculous. Now, he awaits the talents’ arrival. Hart had been partnered with Rodgers in previous decades, and together, they made Pal Joey, A Connecticut Yankee, and Babes in Arms, among others. He hopes to convince Rodgers to reteam on a musical about Marco Polo. But it won’t happen. Rodgers and Hammerstein will become “America’s Gilbert and Sullivan”—the most successful musical team in Broadway history, responsible for Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I, and The Sound of Music. A self-pitying alcoholic, Hart will die in a few months from pneumonia.

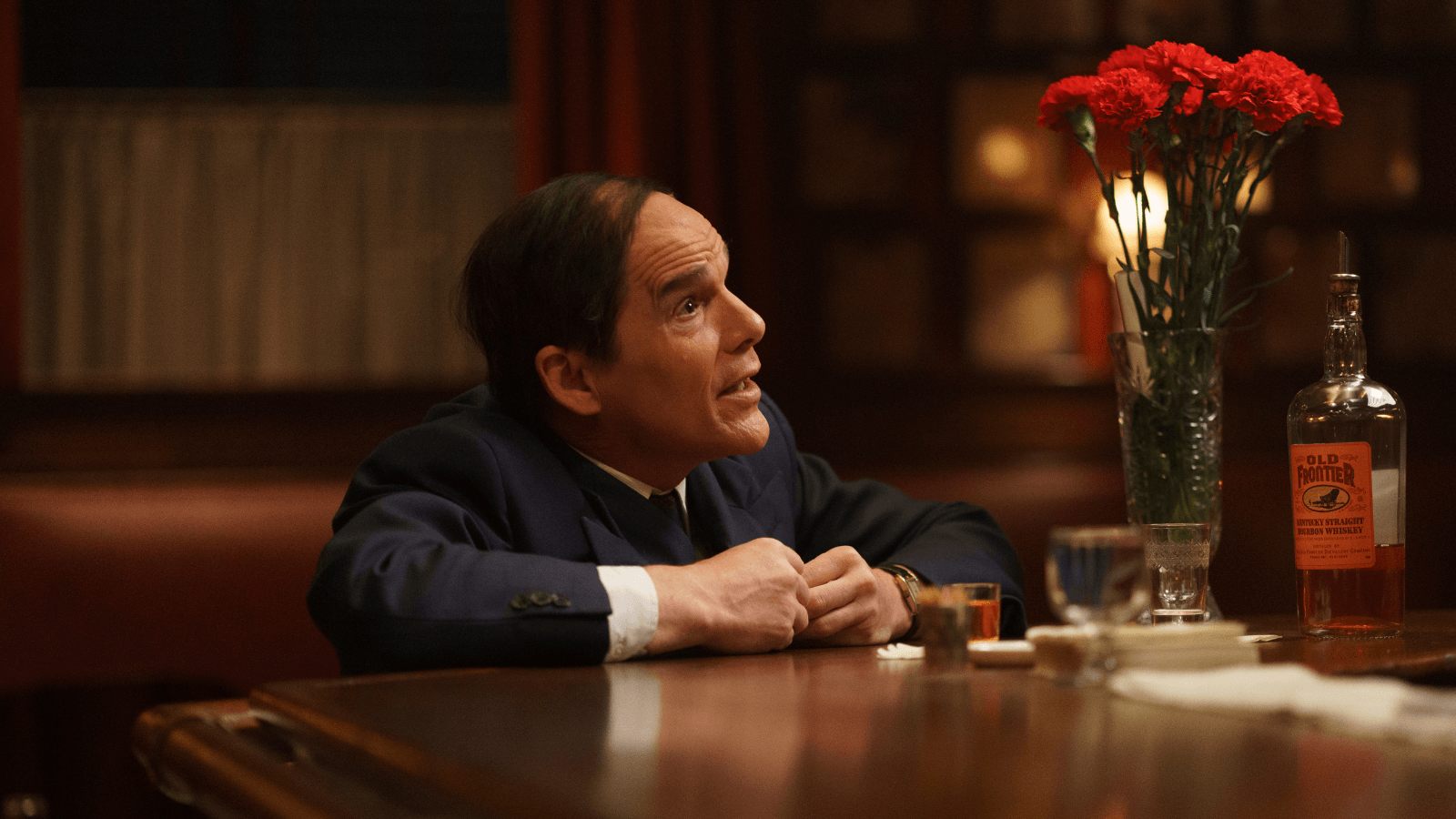

Richard Linklater directs this stagey drama, penned by Robert Kaplow, who wrote the book on which the director’s Me and Orson Welles (2009) was based. Aside from an opening sequence in the theater, Blue Moon takes place entirely in Sardi’s, recreated in detail by production designer Susie Cullen and shot in atmospheric yet theatrical light by cinematographer Shane F. Kelly. The film unfolds with Hart at the bar, monologuing to his bartender, Eddie (Bobby Cannavale), and a piano player, Morty (Jonah Lees), about his past successes and plans for the future. However, there’s an air of desperation about Hart. His heyday has passed, and he knows it. “You know how in marriage they ‘for better or for worse’?” he remarks. “I think in my life I’ve entered the ‘worse’ part.” But that doesn’t diminish his ego, or at least the pretense of one. Hart alternates between bombastic, self-obsessed brags about his legacy and a wounded acknowledgment of his waning career.

Linklater is no stranger to talky material. Most of his films involve characters waxing philosophical or talking about their lives and experiences. Blue Moon is a character study of Hart, who does most of the talking as he works the room. In a thread worthy of Forrest Gump (1994), Hart interacts with a cross-section of twentieth-century creatives: He plants a seed in the brain of E.B. White (Patrick Kennedy) that will germinate into Stuart Little. He encounters Stephen Sondheim (Cillian Sullivan), the crime photographer Weegee (John Doran), and advises a young man named George Hill (David Rawle) to tell stories about friends, not lovers. And even though Hart laments Oklahoma! and its unnecessary exclamation point, he prepares to reconnect with Rodgers to prove that his erratic behavior and undisciplined work ethic of the past are no longer problems. However, his inability to abstain from drinking as he prepares to speak with Rodgers sober reveals his insatiable lack of self-control.

Indeed, Hart reveals that he hasn’t changed much. What’s more, his ideas prove outmoded, crude, and rooted in satire, whereas Rodgers wants to write emotional material with a collaborator who takes their profession seriously. A somewhat closeted gay man, Hart also flirts with a young protégé, Elizabeth (Margaret Qualley, whose modern sensibilities are ill-suited to this period piece), a character based on Hart’s letters to an unidentified Yale coed. Elizabeth knows Hart’s tastes and divulges a tawdry tale in Sardi’s coat room, much to his delight. All the while, Kaplow’s script might be better suited to a one-act play, which would be familiar territory for Linklater (see 2001’s Tape). The material quickly exposes a tragic quality to Hart, captured in his misguided belief that no one loved him as much as he wanted. Hart greedily wants undying devotion but receives only an appreciation of his craft, which is fleeting since he hasn’t written a hit in years.

Unfortunately, most of Blue Moon’s potential has been offset by Linklater’s choice to present the diminutive Hart, who stood under five feet, through a series of off-putting forced-perspective camera tricks to make Hawke appear shorter. The effect recalls how Peter Jackson made hobbits and dwarves look small in his two Tolkien trilogies. But unlike fantasies that require a suspension of disbelief, Linklater’s production strains credibility with the effect, presenting a constant visual incongruity that suggests Hawke spent the entire production on his knees. The effect is a continual distraction that never convinces. Moreover, Hawke looks silly, acting behind brown color contacts and under a garish prosthetic combover, forcing one to wonder why Linklater didn’t hire someone who better resembles Hart or, preferably, ignore the detail about his height. Instead, I found it impossible to appreciate Hawke’s performance or the central character because of his bafflingly odd presentation.

Linklater and Hawke have had one of the most compelling director-actor collaborations in film history, spanning his temporal projects, including the Before trilogy and Boyhood (2014), as well as his more experimental fare, such as Waking Life (2001). Except for The Newton Boys (1998), Blue Moon might be the most uneven of their collaborations, but it’s not for lack of potential. Kaplow’s script and many aspects of the handsome production remain admirable, thoughtful, and polished. However, Hawke’s flamboyant caricature is woefully misguided, and not just because of how Linklater deals with his height. With Kaplow’s terrific script dropping references galore, Blue Moon might play as catnip to some fans of musical theater, but the material feels robbed of its dramatic force by Hawke’s awkward appearance—not from a bad performance, but an ill-advised look. Doubtless, some will not get as hung up on this detail as I have, and hopefully, they can better appreciate Blue Moon for its clever dialogue and otherwise assured direction.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review