Big Man Japan

By Brian Eggert |

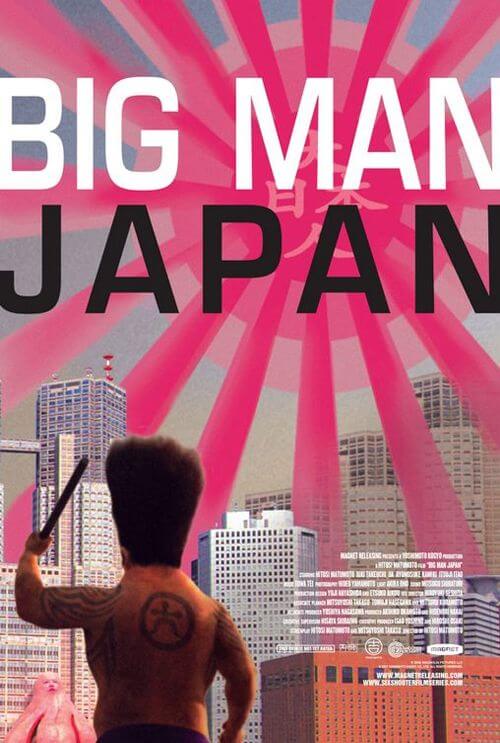

There might never be a stranger movie than Big Man Japan, and if you find one, be sure to let me know. This dry-humored pastiche sends up Japanese superhero television, or tokusatsu (think Power Rangers or Ultraman), and the mega-monster subgenre kaiju (think Godzilla or Gamera). Best identified through massive creatures, some good and some bad, battling in densely populated cities, destroying everything in their path, the genres are staples of Japanese entertainment and much-spoofed in the United States. The film examines one giant-sized hero assigned to stop these monsters, what he would be like in real life, how he spends his downtime, how the Japanese people react to his presence, and how he fits into those gargantuan purple underpants.

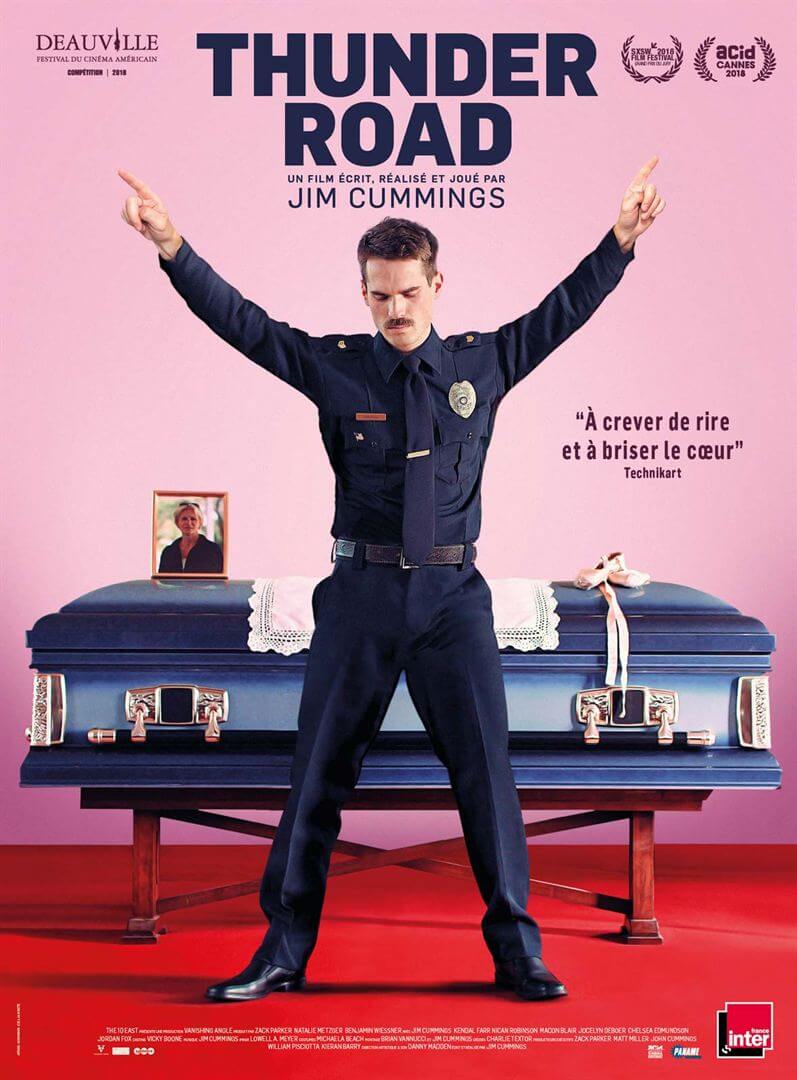

Writer, director, and star Hitoshi Matsumoto pokes fun at mockumentaries and reality television through his setup. A film crew follows loner Masaru Daisato (Matsumoto), the most recent in a long line of heroes employed by the government to protect Japan from monsters from who-knows-where. When not working, Daisato looks like you or me, and he’s awkward and quiet. An off-camera interviewer asks about a wife and daughter, and Daisato admits that they’re indefinitely separated. He’s a sad sort, always wearing dorky hats and never knowing what to say. He likes retractable umbrellas because you can decide when they’re big or small, whereas he doesn’t have a choice—he’s on call 24/7 should a monster arrive. Outside his humble home, where he lives a modest life on his pithy salary, non-fans have left hateful signs and graffiti telling him to stop littering, that he causes more harm than good through his really, really big exploits.

When trouble arises, Daisato rushes to one of three nearby power plants, where they connect electrodes to his nipples. He receives a dose of electricity while standing inside two-story purple underwear. And when the current causes his body to fill out, and he grows as tall as a building, suddenly, his Hanes fit just fine. His enlarged frame blocky and thick, his hair vertical and flat-topped, he stands ready for battle with a club in hand, known to all in this form as Big Man Japan. He’s covered in his sponsors’ tattoos, as his snotty agent, preoccupied with his ratings, is concerned only about earning herself yet another new car. She’s evidently taking more than fifteen percent.

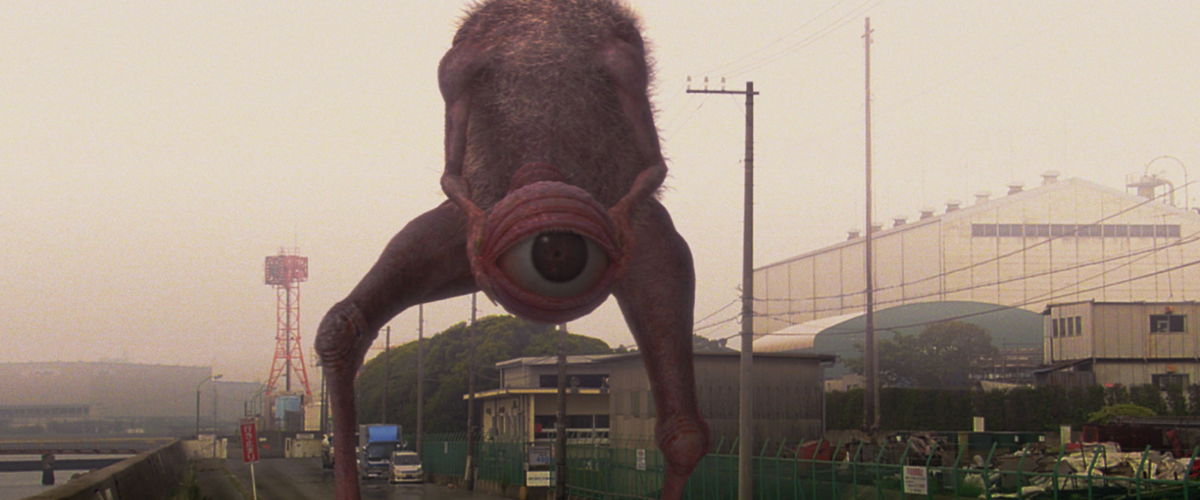

His battles are filmed and aired on late-late night television, though he used to be in prime time. Audiences don’t care anymore, which is curious; they should be more grateful. After all, he’s protecting Japan from quite an assorted array of monsters: The film’s first monster sports a comb-over and wraps large bands around buildings to fling them behind his back. Another monster has one huge eye on the end of a tendril connected to his belly, whirling it about like a mace. One just loiters about the city, stinking it up with cloudy green flatulence. Another monster is simply a huge baby, which Big Man accidentally drops and kills, hurting his public image. Ratings finally go up when he comes face-to-face with a red devil-like monster, which kicks Big Man in the face enough times to make our hero run away in terror.

So why are Japanese audiences ungrateful? Maybe they’re just unimpressed by the intentionally bad special effects used to render the monster battles. No actors in foam suits are used, at least not at first; there’s only subpar CGI that renders these fleshy monsters. The buildings are not fragile miniatures used to break the falls of monsters, and Matsumoto employs no typical shots cutting away to exclaiming bystanders. In fact, you’ll see no bystanders at all, probably because they were too expensive to animate into the scene, and so battles have an eerie silence about them. All remains so until the final sequence, when Matsumoto changes his film into a cheesy TV production filled with all of the above-mentioned omissions like foam suits, cheap sets, visible strings, and so forth, completely forgetting about everything that came before it. The shift is weird and funny and baffling.

Don’t waste your time trying to analyze which nationality this or that monster represents, though America, China, and North Korea all seem to be in there somewhere. Doubtful any nationalistic commentary takes precedence for Matsumoto’s comic intentions, which admittedly inspire hearty belly laughs throughout. His wild physical humor contrasts the aridity of the characters, making for an unusual mix of comedic styles, all further supported by the outlandish plot. Understandably, many of the jokes will be lost on American audiences, since the references are not from our own popular culture, not to mention what’s lost in translation.

Magnolia Pictures picked the film up for distribution in the United States through the Six Shooter Film Series; they’re the same company that flubbed up the translation on the DVD release of Let the Right One In, so who knows if the subtitles are correct (at times, particularly where the dialogue references money, it’s clear they’re not). Regardless, the humor still communicates through universal devices like visual gags and satire. Through it all, Big Man Japan manages to be truly original, something beyond description that you’ll have to see to believe or even understand, if understanding it is even possible.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review