Avatar: Fire and Ash

By Brian Eggert |

Isn’t it curious how each Avatar movie manages to fade from memory almost immediately after it’s over? Why, upon a first-time viewing or even a second watch, do they exhilarate and remind us of James Cameron’s incomparable showmanship, only to evaporate from the mind shortly thereafter? I suspect it’s because the story and characters remain the weakest aspects of Avatar (2009) and Avatar: The Way of Water (2022). They’re unquestionably thrilling spectacles, with eye-popping visuals set on the luminous alien world of Pandora. But the anticolonial conflict follows a familiar narrative path and teems with bland tropes, leaving us moved by the wonder of Cameron’s visual conceit and less so by his storytelling. Avatar: Fire and Ash follows the same pattern. I waited a few days after Cameron’s part three to begin writing this review, and sure enough, his latest has already started to vanish from my memory banks. And while staying power certainly factors into any assessment of a movie, I’m also certain that, should I watch it a second time, I would be thrilled and diverted once again for the duration.

For Fire and Ash, Cameron’s Avatar problem is amplified by the screenplay, authored by the director and the husband-and-wife team of Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver. They implant a nagging sense of sameness throughout. Many of the conflicts that pervaded The Way of Water are replicated in its sequel: In a military operation headed by General Ardmore (Edie Falco) and overseen by Giovanni Ribisi’s corporate goon, the human “Sky People” continue to push for control of Pandora to exploit its natural resources. The late Colonel Miles Quaritch (Stephen Lang), his replicated consciousness now inhabiting a Na’vi body, continues to hunt for the rebel leader Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), another human who “went full Na’vi.” Grieving over the loss of their eldest son, Jake remains in hiding with his Na’vi wife Neytiri (Zoe Saldana) and biological children, the young Tuk (Trinity Jo-Li Bliss) and angsty teen Lo’ak (Britain Dalton), whose intermittent narration adds little to the overall structure. They also consider Kiri (Sigourney Weaver), the teenage messiah, and Quarich’s human son Spider (Jack Champion) their children.

New to the story is an angry tribe of Na’vi called the “Ash People,” led by Varang (Oona Chaplin, daughter of Geraldine and granddaughter of Charlie). Varang believes her people’s bad luck means that the Na’vi’s nature god, Eywa, has abandoned them. Marked by their stark red makeup, ashen skin, and shaved heads that make them look like vampirish ghouls, the Ash People attack other tribes. Varang brainwashes them into obedience with a combination of psychedelics and her kuru (the tendril that allows Na’vi to connect with flora and fauna). In a desperate move to capture Sully, Quaritch forms an unholy—but very horny—alliance with Varang. Elsewhere, the callous Captain Mick (Brendan Cowell) plans to invade a sacred ceremony of Tulkuns, Pandora’s superintelligent whale-like species, to harvest their life-sustaining brain gel that sells for billions on Earth. This leads to a convergence of various conflicts near the water-centric Metkayina tribe’s island community, mirroring the one in The Way of Water, only on a much larger scale.

![]()

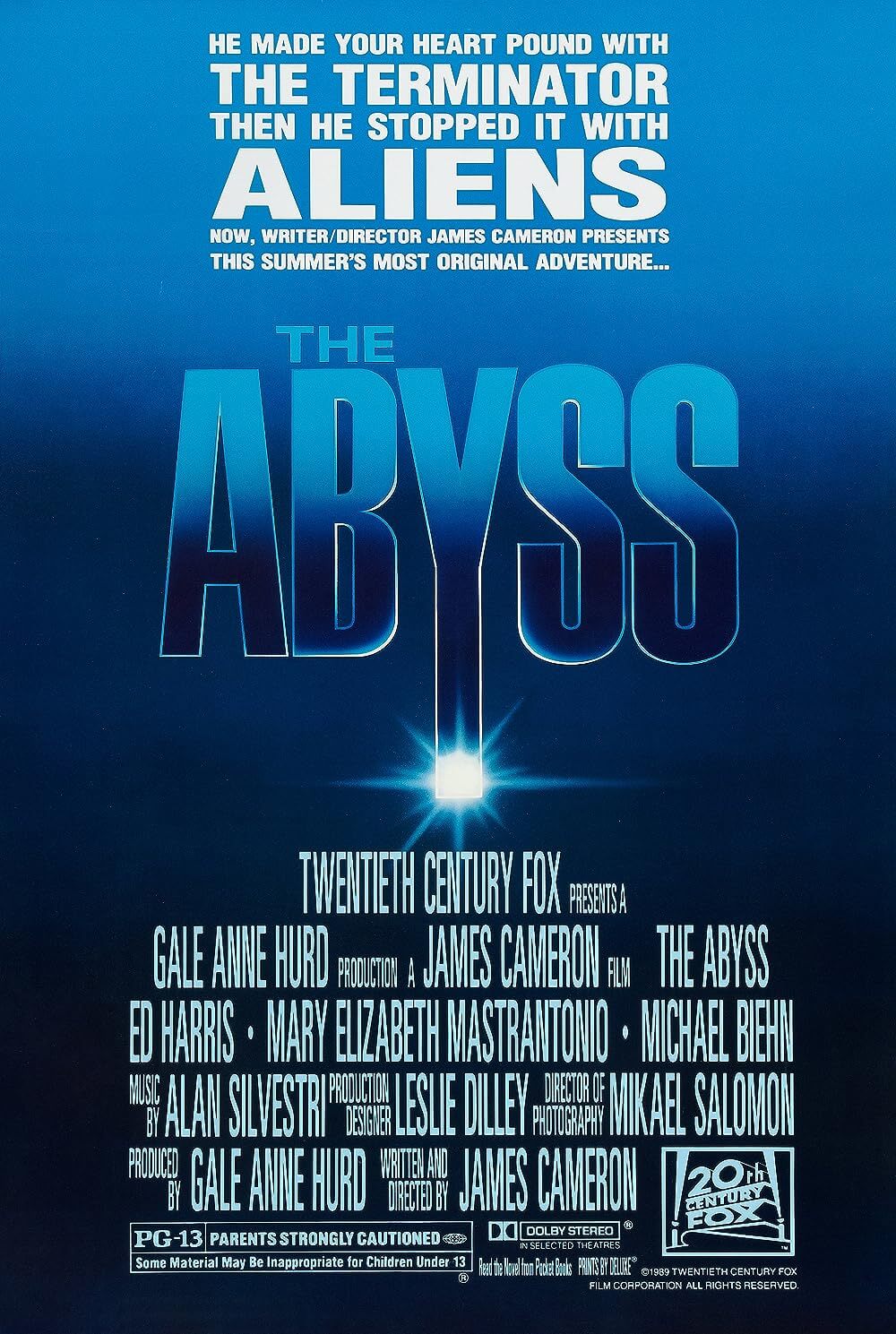

Apart from a few new wrinkles—including Kiri’s emerging connection with Eywa, which inspires her to save the air-breathing Spider by converting his respiratory system to a Pandora-friendly model—the conflict proves almost identical to The Way of Water. The Sully family experiences more discord in the ranks, particularly because Jake secretly blames Lo’ak for his elder son’s death. Neytiri and Jake clash over her increasing intolerance of humans, whom she calls “pink skins.” Quaritch vaguely questions his loyalties. The Tulkuns abhor violence, unlike their outcast brother Payakan, and eventually they face a decision: fight or die. The humans prove mostly awful, save for Jemaine Clement’s marine biologist character, who finally gets a backbone. Inevitably, as Cameron often does—see Aliens (1985), The Abyss (1989), Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), et al.—he funnels the movie’s many subplots into a grandiose finale that, despite its familiar setup, thrills to no end.

Fire and Ash meanders a bit through these subplots, and that makes the 3-hour-and-15-minute runtime, the lengthiest yet, feel overlong and unearned. By the end, this sequel doesn’t accomplish much. The movie curiously forgets about Varang. Quaritch’s fate is equivocal, meaning he’ll probably return for the proposed 2029 sequel. The Sky People will undoubtedly regroup and return in force. Perhaps Cameron has settled on the same philosophy as the characters in this year’s One Battle After Another, where the fight never ends, it just takes on alternative forms. Fortunately, the writers have cut down on Lo’ak and Spider’s annoying use of “bro” at the end of every sentence, despite it being the third word spoken in the film. Elsewhere, the biblical allusions continue beyond Kiri as Pandora’s resident Jesus; there’s also an Abraham parallel between Jake and Spider. And with Spider’s newfound abilities to breathe Pandora’s atmosphere, he holds the secret to homo sapiens colonizing the planet. Will Jake follow Neytiri’s advice and sacrifice Spider for the greater good? Hmm, what do you think?

![]()

Most of these story elements amount to a serviceable-at-best application of narrative. Like the cracker that carries some brie and chutney to your mouth, it’s a base-level conveyance. In this case, the narrative conveys a visual morsel—a delectable display of colors and sensations. Every shot, every action sequence evokes awe, with convincing-looking characters rendered from motion-capture animation and detailed environments that transport the viewer to this alien world. Fire and Ash has been made available in a variety of different formats (standard, 3D, HFR, and various combinations thereof). I attended a press screening in Dolby Cinema, featuring the 3D version in HFR (running at 48 frames per second, twice the cinematic standard of 24fps). The 3D gimmick alternates between immersive and distracting, particularly because I must wear those glasses over my prescription glasses, and I spend half the show adjusting my doubled-up eyewear. And the HFR, which looks like your grandpa’s flatscreen TV when he has that “motion smoothing” effect on, comes and goes, appearing mostly during action sequences—an improvement over the incessant HFR in The Way of Water. Given these unnecessary accoutrements, I look forward to when I can watch Fire and Ash at home on a UHD disc on my OLED TV. I’ll probably enjoy it more.

And last thing’s first: Before the movie begins, Cameron appears onscreen to assure viewers his production was “not made by generative AI.” He shows a splitscreen from the production process, with actors performing their lines in mo-cap suits next to the completed effect. But the keyword here is “generative,” meaning artificial intelligence that operates according to user prompts. However, Cameron does not acknowledge that many of the digital artists and their tools use AI-assisted technology to complete visual effects. Nor does he address how badly he botched recent restorations of Aliens, The Abyss, and True Lies (1994) using AI tools. No matter. It’s evidence that Fire and Ash isn’t the product of someone relying on AI to flesh out the details or conceive this elaborate world. Cameron pours himself into every frame of his Avatar movies, revisiting themes and obsessions found throughout his filmography, and his enthusiasm is infectious. As ever, his technical craft is impeccable, and those who purchase tickets will surely feel it was money well spent. However, my hope is that Cameron imbues the next visit to Pandora with different stakes that don’t feel like another retread, only bigger.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review