Reader's Choice

A Touch of Sin

By Brian Eggert |

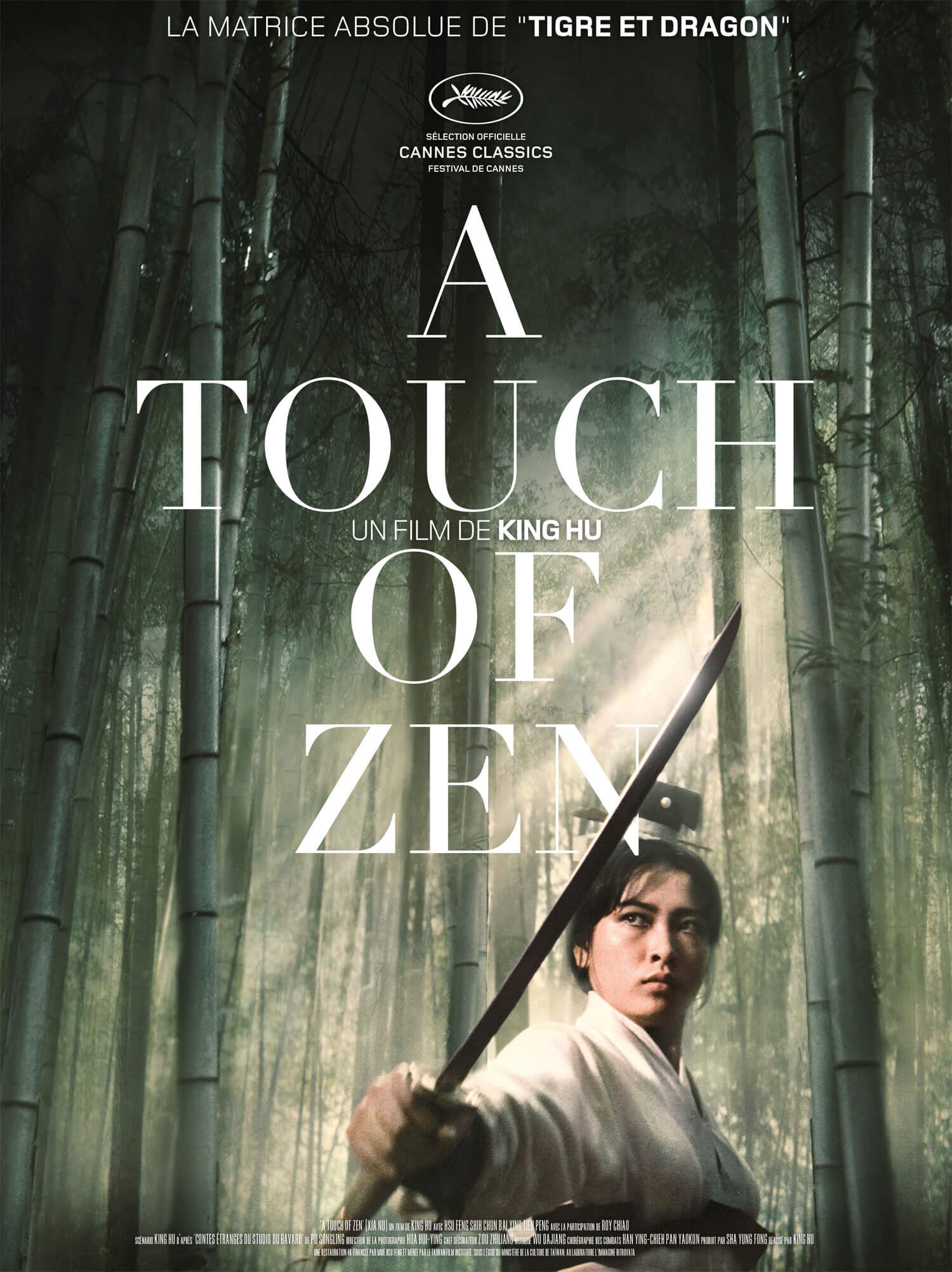

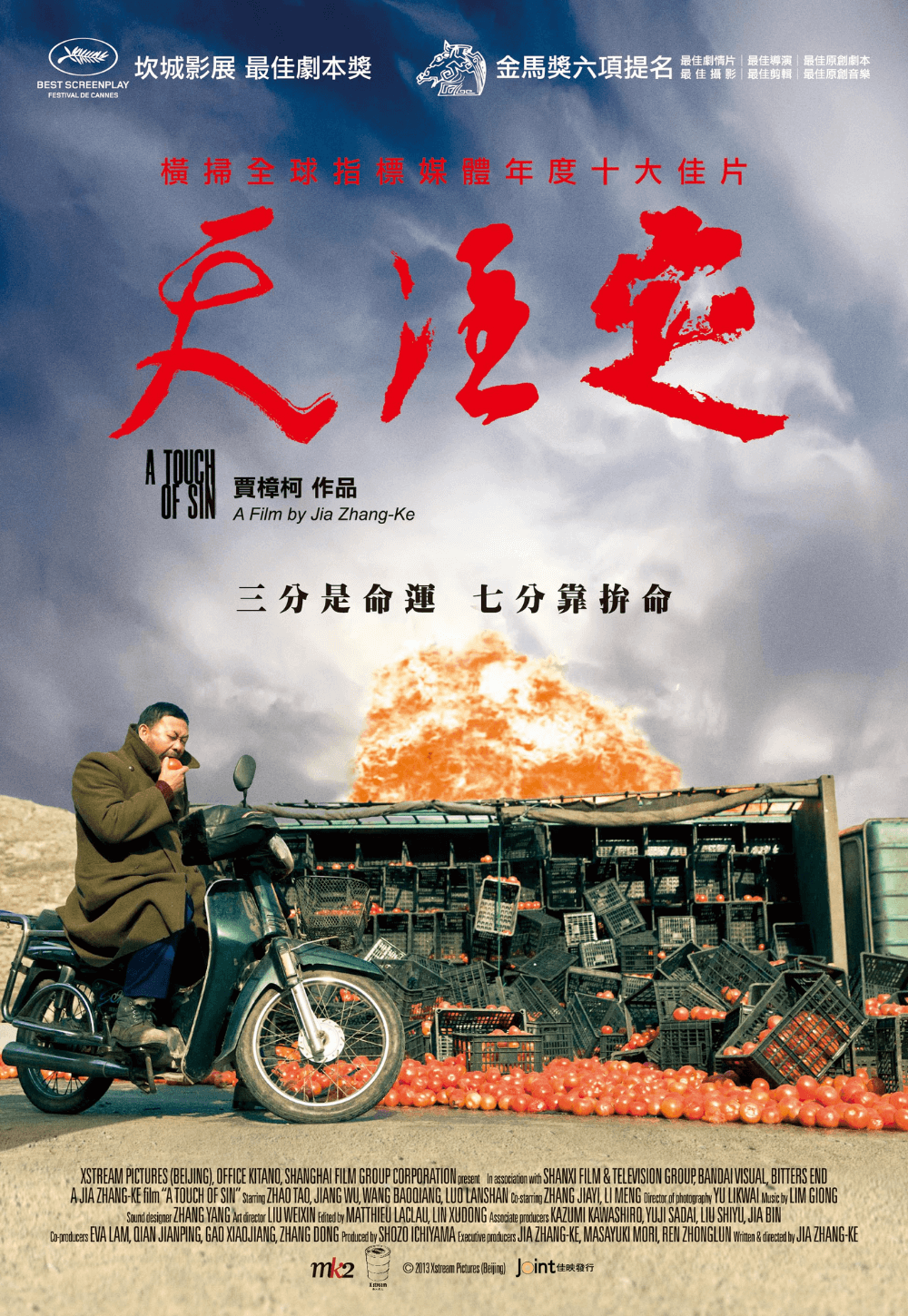

Jia Zhangke has described A Touch of Sin as a “martial arts film for contemporary China.” The title pays homage to King Hu’s wuxia epic, A Touch of Zen (1971). However, the comparison may seem faulty at first glance. Hu’s existential period piece involves chivalrous knights-errant who travel the land and seek out noble adventures, leading to a rather unconventional three-hour meditation on fighting for honorable causes; how women, too, can serve as warriors; and Buddhist transcendence. By contrast, Jia’s film adopts an anthology format, telling four distinct but superficially interwoven stories, each loosely based on actual events that occurred in contemporary China. Each finds its protagonist exposed to the corruption, humiliation, and despair that result from a capitalist system. Its characters respond with bloody violence, either because they’ve reached their limit or resolved that violence is the only solution. Between the portmanteau format and modern-day setting, the two films seem to have little in common. However, the association invites comparison and leads to Jia’s transgressive confrontation with the consequences of China’s dramatic embrace of capitalism.

Jia’s cinematic output took a sharp turn in 2013 with A Touch of Sin. Until this feature, the underground filmmaker had combined docu-style observation with elliptical commentaries on the downsides of China’s rapid globalization. The Sixth Generation filmmakers’ works, such as Xiao Wu (1997), Platform (2000), and Unknown Pleasures (2002), unfold in long, slow passages, exploring social realism and elliptical narratives. Yet, he sprinkles them with the slightest affectations—for instance, the appearance of UFOs in Still Life (2006) and Ash is Purest White (2018)—to remind his audience that they’re watching a drama, not a documentary. His films to this point belonged in the category of arthouse works, often deemed too politically volatile by the Chinese censors and too experimental for mainstream international audiences. The censors denied each of his films exhibition in mainland China until The World (2004). A Touch of Sin addresses many of the themes and visual motifs Jia uses in his earlier work, except he exploits the moviegoer’s taste for genre violence, creating a cinematic spoonful of sugar to help his social critique go down.

Jonathan Romney’s review in Film Comment notes that Jia employs “cinematic fakery”—in other words, escapism and genre conventions—to confront more than just the reality of China’s hollow, corruptive embrace of capitalistic values. Rather, the director quite controversially frames his desperate, beleaguered characters as heroic, if tragic, figures who resort to violence and criminality to solve their problems. Jia’s film suggests that in a world so unscrupulously devoted to the social hierarchies of capitalist society, where the rich have the power and the underclasses must adhere, there’s only one solution: fight against injustice in the manner of a knight-errant. Jia sees his characters’ real-life struggles as tantamount to martial arts fare, where a lone person faces corruption and crisis, so they take matters into their own hands. But this is not to say A Touch of Sin endorses violence; instead, it is a critique of the systems in place, from governmental corruption to corporate exploitation of the working class, that compels people to respond with violent action. The violence is disturbing and tragic, and it would be altogether unnecessary had socioeconomic systems been fair and balanced.

Jia divides his film into four distinct parts, each set across the expanse of China, ranging from North to South, and each surrounding the Spring Festival. The first story takes place in Jia’s home in the northern province of Shanxi, drawing from an actual 2001 incident where a former miner, Hu Wenhai, shot and killed several corrupt officials in his village. He explained before his execution in 2002: “Officials are forcing people to rebel. I can’t let these assholes squeeze people any more. I know I’m going to die, but my death will get the attention of those officials.” In Jia’s telling, coal miner Dahai (Jiang Wu) learns that his village leader and a well-to-do former classmate have colluded, with crimes ranging from bribery to embezzlement, to monopolize the local mines. Though he attempts to raise his concerns through the proper channels, the authority responds with dismissal, public humiliation, and an attempted bribe. Dahai snaps and goes on a shooting spree, targeting the village chief and accountant. He even takes out a local man for brutally whipping a horse. He seems to feel a brief moment of relief as police cars approach.

But not all stories in A Touch of Sin feel so cinematically cathartic. The film opens with a prologue with San’er (Wang Baoqiang) riding a motorbike home to celebrate the Spring Festival with his elderly mother. When a trio of thugs try to rob him, he unceremoniously shoots all three. Later, after Dahai’s story, the film picks up with San’er celebrating his mother’s birthday, raising questions about how he can afford his lifestyle. The answer comes in the ensuing scenes when he murders two people leaving a bank in Chongqing before taking off on his motorcycle. Jia drew inspiration from Zhou Kehua, who killed 10 people in a series of armed robberies between 2004 and 2012, when he was shot to death by police. Whereas the real-life figure was a reported mercenary and arms dealer, Jia shows him to be a family man who fights for his autonomy violently. San’er’s story reveals that Jia does not defend such an enthusiastic gun-carrying murderer; rather, it reveals that San’er views himself as free and outside the economic system.

In the third story, Zhao Tao, the director’s wife and regular collaborator, stars as Xiaoyu. She hopes her lover, a private businessman, will leave his wife for her. Meeting him in Yichang, they have a familiar conversation where he makes excuses for leading her on before returning home. Disappointed, she takes a train back to Hubei to her job as a spa receptionist, only to be confronted by her lover’s wife, who calls out their affair. Xiaoyu tries to relax afterward but finds herself pressured by clients wanting a massage. Despite her refusals—and multiple retaliatory slaps on her part, in a scene that underscores Jia’s unexpected genre-inflected intentions—they make unwanted advances, confident that anyone can be bought. Then they become abusive, shouting, “I’ll smother you in money!” Pushed to her limit, Xiaoyu responds by desperately, impulsively stabbing them with a knife. After getting herself out, she calls the police to turn herself in. The actual incident took place in 2009, involving a pedicurist named Deng Yujiao, who fended off a sexual assault by killing her attackers. The authorities charged her with homicide, but public outcry in her defense led to reduced charges and no jail time.

Rather than end his film with a bang as a martial arts feature might, Jia’s fourth story centers on Xiaohui (Luo Lanshan), a migrant worker whose idle workplace conversation leads to a coworker’s injury. In a twisted policy, the injured worker will be paid from Xiaohui’s salary. To avoid this, Xiaohui leaves for Dongguan, where he finds work in one of the city’s many “hostess” clubs. It doesn’t take long for him to fall for a hostess, Lianrong (Li Meng), but she has a child and no intention of stopping her sex work for him. With pressures building—the injured ex-coworker plans to beat Xiaohui for leaving, and his mother scolds him for not sending money home—Xiaohui commits suicide by leaping to his death. His story resembles that of over twenty workers, all in their twenties or younger, who were employed in the Foxconn City industrial park (called “iPhone City” given that it produces the majority of Apple products) and committed suicide due to the unforgiving working conditions. If it seems at odds with the external violence demonstrated in the earlier stories, it’s no less about violence, albeit self-inflicted.

Jia modeled his screenplay after the structure of an essay, with its four stories representing the components of a written argument—complete with an introduction, analysis of evidence, deviations, and a conclusion. However intellectually controversial the ideas in A Touch of Sin may seem, Jia confronts a reality in Chinese culture and many cultures around the globe that violence solves political problems, though morally abhorrent. Mao Zedong famously said, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Jia links this belief with Chinese cultural history’s depiction of the chivalrous knight-errant who fights against crime, injustice, and tyrants. In each case within the film, the political economy represents an inescapable framework the character can no longer inhabit due to their conscience, emotional reality, or active defiance. This represented a stark critique that prompted the Chinese Film Bureau, which had initially approved of A Touch of Sin, to rethink its release despite winning the Best Screenplay award at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, fearing it “might provoke social unrest.”

Telling ripped-from-the-headlines stories in a stylized manner, Jia also nods to wuxia cinema, as established, but scholar Wang Xiaoping notes that he borrows from Peking operas in his use of costumes and postures. Note how Zhao Tao’s character wields a knife in a pose recalling Hsu Feng’s dynamic action postures, most memorably in King Hu’s A Touch of Zen. The influence of Chinese opera on wuxia remains inextricable. These influences suggest that just as Jia’s debut film Xiao Wu stood as a parallel to Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), A Touch of Sin finds the director embracing heroic tropes and weaving them into realistic scenarios. What’s exceptional and unexpected about A Touch of Sin is how well Jia handles the aesthetics of violence, presenting a pointed change in his style that, along with his familiar themes, still feels like a Jia Zhangke picture. To be sure, the ending is pure Jia: An epilogue finds Xiaoyu in a public square, watching a performance of the opera The Trial of Su San, in which a character asks, “Do you understand your sin?” Jia puts that question to his audience, prompting us to consider what role Chinese citizens, or citizens of the world, have played in the exploitation and oppression of others.

“These are all tragedies,” Jia said of his segments. But they go beyond mere one-off incidents when viewed together in an anthology. They reveal a pattern of China’s rapid changes leading to people being unable to cope, resulting in outbursts of violence. A Touch of Sin is a protest film in the guise of a thriller, using the appeal of cinematic violence to shake its audience out of its apathy toward real-life tensions and recognize the illusion of the Chinese government’s self-proclaimed “harmonious society.” Jia’s anger over the fates of his characters is palpable. When viewed within his filmography of experimental cinema, documentaries, and connective tissue between them, A Touch of Sin’s narrative methods—as an anthology film, a tale of violence—register as anomalous. However, they support the director’s enduring questions about China’s façade against the grim consequences of their relentless capitalist expansion.

(Note: This review was originally posted to DFR’s Patreon on March 19, 2025.)

Bibliography:

Frodon, Jean-Michel. The World of Jia Zhangke. Film Desk Books, 2021.

Jian, Ma. “Shanxi Province slaves not alone.” Taipei Times, 28 June 2007. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2007/06/28/2003367197. Accessed 6 March 2025.

Mello, Cecília. The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2019.

Xiao, Jiwei. “China Unraveled: Violence, Sin, and Art in Jia Zhangke’s A Touch of Sin.” Film Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 4, 2015, pp. 24–35. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2015.68.4.24. Accessed 6 March 2025.

Xiaoping, Wang. China in the Age of Global Capitalism: Jia Zhangke’s Filmic World. Routledge; 1st edition, 2019.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review