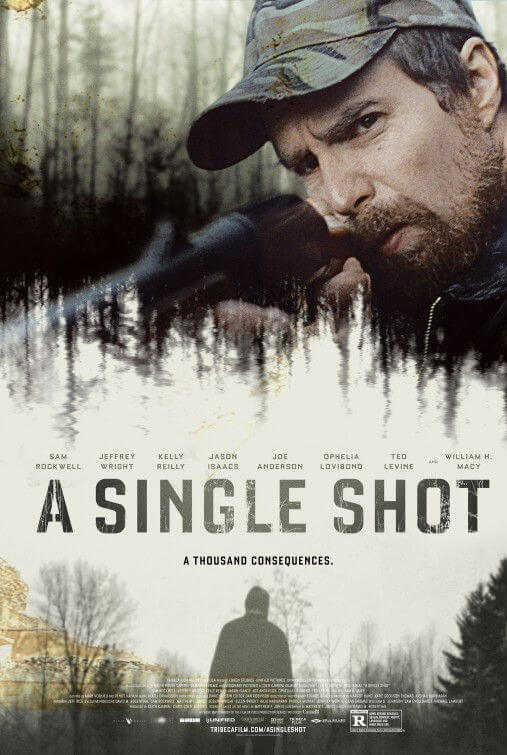

A Single Shot

By Brian Eggert |

John Moon survives in the backwoods by poaching game on a nature preserve, a crime for which he’s been reprimanded before. A loner rifleman who not only lost his family’s dairy farm to the recession but whose wife Jess (Kelly Reilly) left him and took their young boy with her, Moon is played by a bearded, leathery Sam Rockwell, an actor born to play lowlifes and eccentrics. On one of his hunts, Moon tracks a deer and, before checking his target, fires through the trees. He inspects his kill, and he discovers he’s accidentally shot and killed a young woman, an apparent runaway. In shock and afraid the accident will land him in jail, given his sordid history in the surrounding woodland, Moon looks over her camp and finds a box of cash, possibly enough to buy back his family farm and win over his estranged wife. In a panic to cover up what he’s done, he takes the money but remains unprepared to hide his secret from anyone who might already be looking for the victim.

A Single Shot reaches for a hillbilly noir on par with Winter’s Bone or Sam Raimi’s A Simple Plan, but it lacks balance between its spare atmosphere and the story’s abundance of overacted, colorful characters. Matthew F. Jones adapted his own novel for director David M. Rosenthal (Janie Jones, 2010), and Jones’ script meanders about with a structure that resists the clearly noir-inspired setup of the plot. An ill-fated protagonist in a familiar scenario, Moon will inevitably cross paths with the money’s dangerous owner and all manner of seedy types trying to get their hands on his newfound loot, leading him down a predictable path of self-destruction. And despite his script’s structural origins in film noir, Jones relies less on suspense and more on a ruminative tone to tell the story. Except, for all of cinematographer Eduard Grau’s gloomy, ponderous shots and the gravitas the writer injects into the dialogue, there’s little meaning found inside.

Moon, not so dim-witted that we lose interest, nevertheless begins to spread his cash around town, drawing unwanted attention. William H. Macy plays a slimy small-town lawyer named Pitt under an intentionally obvious hairpiece, false teeth, and a limp. Pitt is the kind of sleazy attorney no one in their right might would hire, but Moon entrusts him to save his marriage and hands him a wad of cash to do so. And after his eyes have lit up with dollar signs, Macy’s lawyer sniffs around, hungry for more. Meanwhile, Moon stops by Jess’ to deliver some cash and prove he’s worth a damn, but he finds instead the trashy babysitter (Amy Sloan) being bedded by abrasive, tattooed ex-con Obadiah (Joe Anderson) as Moon’s child sleeps in the next room. Arriving later is Obadiah’s boss, Waylon (Jason Isaacs, like Reilly, hiding his British accent with a Southern brogue), the mean baddie who’s obviously the film’s antagonist—a fact which Moon finally realizes long after the audience has figured it out.

Though he’s certainly being watched, Moon resolves to get drunk with his rough-around-the-edges pal Simon (Jeffrey Wright), whose affinity for hooch and easy women offers an interesting performance but some overwrought exposition to clarify the money’s origin. When he’s not getting drunk or pestering Jess to come back to him, Moon resists the flirtations of Abbie (Ophelia Lovibond), the daughter of Moon’s good-hearted neighbor (Ted Levine) who now owns the former Moon family farm and offers Moon a job, a far-too-easy way out for our stubborn protagonist. The plot inevitably leads to a final showdown between Moon and Waylon over the cash, with Abbie, not Jess, as Waylon’s hostage—perhaps because she’s the only character onscreen with a future, and therefore her being in peril raises the stakes. Still, Abbie’s overall brief screentime doesn’t help heighten our involvement.

While the actors in the aforementioned Winter’s Bone and A Simple Plan disappear into their thick roles, the performances in A Single Shot don’t feel like they’re a part of the same world as the story. The other actors seem to be play-acting next to Rockwell, the only performer in the cast who loses himself onscreen. Though Macy is the only person who could make Pitt watchable, Isaacs, Wright, and others are outdone by the preposterousness of their characters. The quality of these performances in A Single Shot depends on Jones’ script, in which too many characters have too few dramatic connections between them. Ultimately, Jones doesn’t have enough for these people to do, and Rosenthal tries to instill meaning but achieves only emptiness through Grau’s vast images and composer Atli Orvarsson’s overuse of a spindly string section. Despite Rockwell’s fine acting, there’s little suspense or emotion to bond us to A Single Shot or its cast of backwater characters.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review