The Definitives

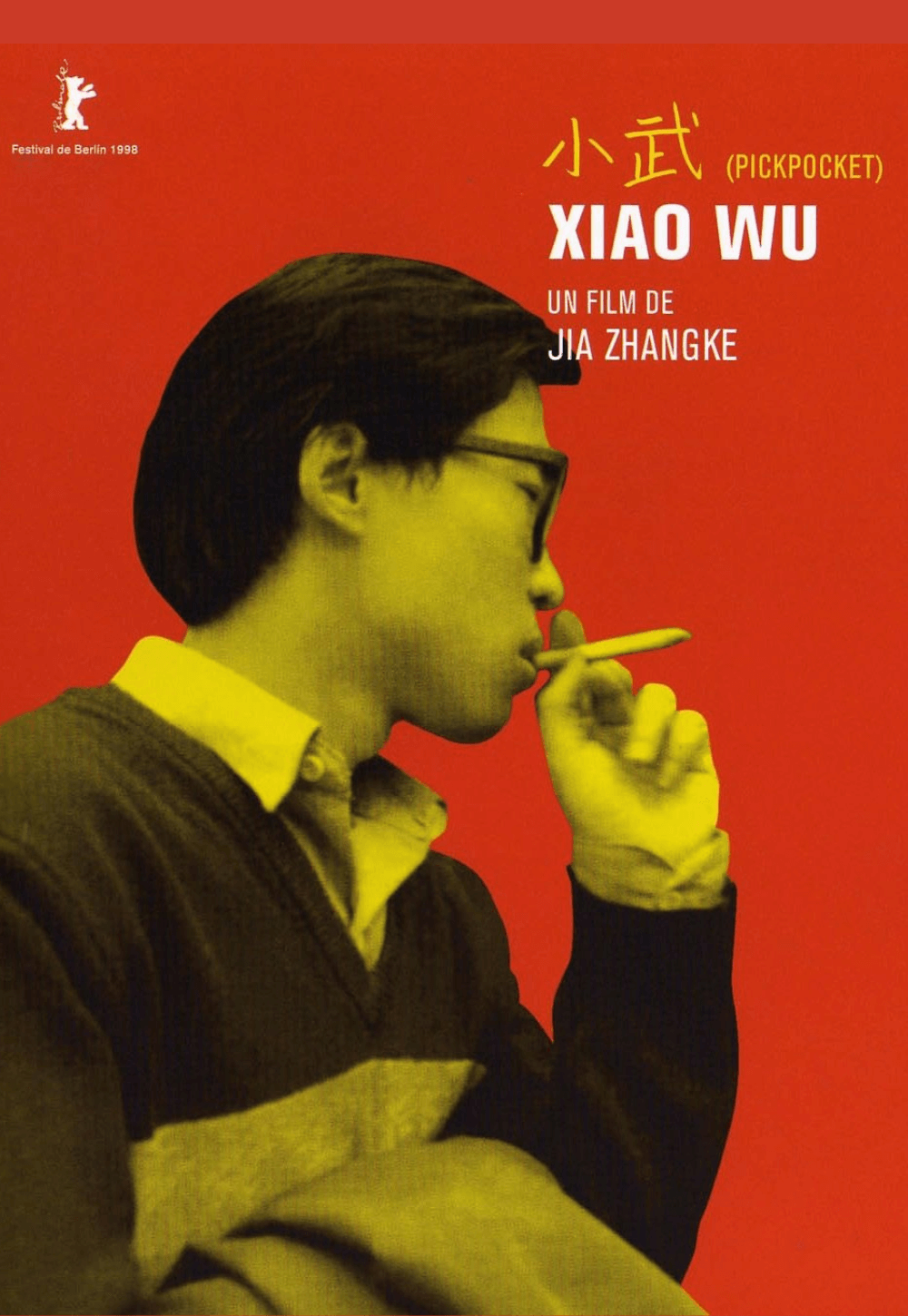

Xiao Wu (1997)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

A pickpocket, Xiao Wu describes himself as “a craftsman.” After all, he earns a living with his hands. In the first scene of Xiao Wu, the debut feature of Jia Zhangke, one of the most celebrated Chinese directors, the titular character boards a bus. He sidesteps the fare by claiming he’s a policeman, which the ticket collector doesn’t believe but also doesn’t question. After scheming his way on, Xiao Wu carefully lifts the wallet of the passenger sitting beside him. The camera then cuts to a Mao Zedong medallion hanging from the bus’ rearview mirror, as though the late Chairman Mao had witnessed this petty crime but, in his current state, remains helpless to do anything about it. The moment illustrates Jia’s interest in the transitional period between China’s Maoist era and the country’s radical reform into a globalized market economy in the 1990s. Centered on its dislocated character, a socially marginalized figure who drifts through his home city of Fenyang, unnecessary to society and therefore an outcast, Xiao Wu (known as Pickpocket in some Western markets) captures how some cannot keep pace with the nation’s rapid changes. Mutating from one era to the next, less in distinct cultural stages than a gradual shift, China’s urgent capitalistic aspirations isolate Xiao Wu and render him a misfit for his failure to adapt. He is ultimately left alienated, targeted, and shunned as socially undesirable.

Completed in 1997 and released on the international festival circuit in the following years, Xiao Wu breaks from the traditional modes of Chinese film. Jia crafts a distinct hybrid cinema, somewhere between narrative fiction and documentary, to present China’s constant state of flux. The result veers away from the look and themes of most Chinese cinema of the late 1990s, much of which stemmed from highly poeticized literature and theater. Such expressivity in Chinese film fueled the popularity of martial arts cinema, particularly wuxia and other fantasy genres. Until the 1980s, China’s cinematic output relied on un-realities, whether embodied by propaganda filmmaking during the Cultural Revolution or lavish historical dramas and other expressive genres in the decade to follow. By contrast, Jia’s boldly realistic portrait of a small-time criminal amid the socioeconomic changes in Fenyang marked an unmistakable divergence from the status quo. His investigation into the relationship between the aesthetics of cinema and his ever-shifting reality—using untrained actors, observational camerawork, and on-location shooting to achieve documentary-level realism—represented a stark formal change compared to most Chinese cinema. Xiao Wu established Jia as China’s premier arthouse filmmaker, whose films create a record of spaces that no longer exist and comment on the human toll of China’s embrace of global capitalism.

Since the mid-1990s, Jia Zhangke has made films in a radically changing and unstable environment. China underwent a stark evolution in a few short decades, and Jia has spent his career recording and considering the implications of its modernization. His work examines this so-called progression while weighing the constant cultural motion and links between the past, present, and future. China’s infrastructural and social development, spurred by Deng Xiaoping’s Era of Reforms in 1978, fostered its emergence in the global economy and led to its morphing physical and social landscape. The push to modernize, urbanize, and become an industrial and consumer-driven economy reshaped cities, altered traditional lifestyles, and elevated China to prominence in international trade and geopolitics. China’s growth since Deng’s reforms has meant a shift in how people inhabit spaces and must move with the change, both physically and ideologically. Because spatiality informs memory and identity to no small degree, Jia has argued that the pace at which China has determined to reshape itself represents a destructive element, given the collateral damage among the country’s people. His films not only chart this damage but dramatize how the vehicle of China’s progress rolls over anyone standing in its way.

Many critics and scholars characterize Jia as China’s most prominent Sixth-Generation filmmaker. However, the label may be too simplistic. The term refers to the sixth grouping of Chinese filmmakers, the first four of which seldom received international exposure. After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 and the reopening of the Beijing Film Academy (BFA), Fifth Generation filmmakers such as Zhang Yimou (Raise the Red Lantern, 1991) and Chen Kaige (Farewell My Concubine, 1992) emerged, telling grand historical epics in sometimes expressive, symbolic imagery. Not until the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 did the Sixth Generation of filmmakers emerge, sometimes operating in underground film movements and conveying anti-authority messages to question matters of alienation in the modern landscape, state censorship, and globalization. While Fifth Generation filmmakers have become ever more concerned with spectacle and appeasing China’s mounting blockbuster industry, films by the Sixth Generation—such as Lou Ye (Suzhou River, 2000) and Wang Xiaoshuai (Beijing Bicycle, 2001)—have made use of smaller budgets, inexperienced actors, real-life settings, and guerilla filmmaking to pursue more personal stories.

Set in the 1990s, Xiao Wu is the first of many Jia films about how globalization leaves people behind in the new China. Throughout the country’s twentieth-century history, various waves of power have sought to establish their dominance by erasing the recent past and resetting for the future. This is evident in the Proclamation for the Republic in 1911, the Communist Revolution in 1949, the Cultural Revolution starting in 1966, and Deng’s Era of Reforms in 1978. Each new regime eradicated the policies of the most recent government and outlined new, sweeping ambitions for the future. Xiao Wu takes place against the backdrop of the Chinese government’s 100-day crackdown on crime, modernization of provincial areas, and expansion of educational reforms. In Fenyang, in the Shanxi province of northern China—Jia’s hometown and the film’s setting—the country’s “Project Hope” aims to tear down old buildings and replace them with new structures. The government also targets unwanted behaviors in a mass rectification and reeducation, calling for authorities to capture criminals and for former criminals to turn themselves in.

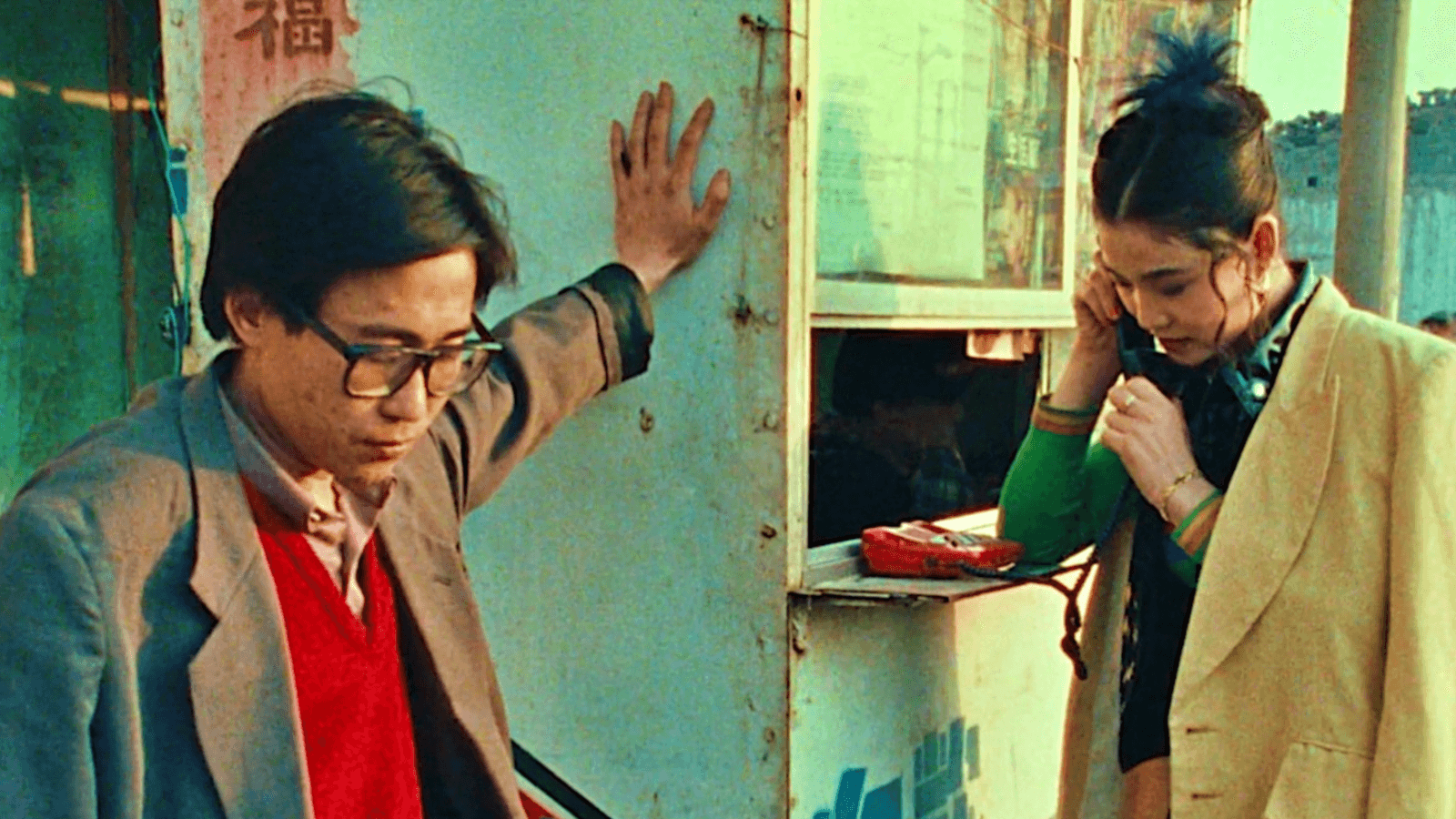

The titular character, played by Jia’s childhood friend and collaborator Wang Hongwei, does not conform to the new way of thinking. He’s a remnant of a recent past, continuing to pickpocket in defiance of the crackdown and local police chief’s warnings to “shape up.” Throughout the film, his choices isolate him from his friends and family. Jin Xiaoyong (Hao Hongjian), his former partner in crime—as shown by their matching gang tattoos—has gone straight. Jin now operates a legitimate “free trade” business involving cigarettes and karaoke bars. He’s also getting married; though, Xiao Wu hasn’t been invited to the ceremony. “You’ve fucking changed,” Xiao Wu tells Jin when he confronts him. It’s a true enough statement; Jin has changed. The problem is that Xiao Wu hasn’t. Perhaps out of retaliation, he steals Jin’s cigarette lighter, which plays Beethoven’s “Für Elise” in harsh beeps. Later, the sound reminds him of his theft and broken friendship. Jin is just one of the many Fenyang locals to accept the new market of beauty salons, karaoke bars, and electronics shops. Mei Mei (Zuo Baitao), a young woman working in a KTV (karaoke television) room, has a brief affair with Xiao Wu. But she abruptly leaves town without telling Xiao Wu, seeing no future with him. Even Xiao Wu’s family rejects him as a “black sheep” after he reteats to them, and they argue over the origins of a ring he attempts to give his mother.

Jia saw dramatic changes like this firsthand. Born in 1970 in Fenyang, he grew up during the Cultural Revolution and survived in impoverished conditions for years. But Jia’s home life improved throughout the 1980s as China welcomed Deng’s market-centric reforms. Jia went on to study fine arts, specifically poetry and painting, in Taiyuan. He only resolved to attend the BFA in the 1990s after seeing Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth (1984)—one of the formative Fifth Generation Chinese films that, for the first time, adopted Western modes of filmmaking in support of a new poeticism. However, Jia and his contemporaries did not follow the examples set by the Fifth Generation’s Chen and Zhang Yimou, who adopted realistically conveyed historical settings to create parallels to modern-day issues. While studying film theory, Jia also developed an appreciation for European auteur filmmakers, such as Michelangelo Antonioni (Red Desert, 1964), Robert Bresson (A Man Escaped, 1956), and Vittorio de Sica (Umberto D., 1952)—filmmakers who tackled contemporary issues in aestheticized ways. Like many of Jia’s fellow Sixth Generation filmmakers, he was inspired by these filmmakers to create films about where humanity fits within the swiftly developing urban landscapes across his country.

Beyond his interest in realism and national expansion, which would initially pigeonhole his work into the Sixth Generation, Jia distinguishes his cinematic arguments by blending commentary about China’s globalization with more artistic traditions found in painting, literature, architecture, photography, and popular music. For instance, his inclusion of pop music underscores the transformation taking place in mainland China—epitomized by his frequent use of Teresa Teng, a Taiwanese pop star whose music hit the mainland in the 1980s. Her widespread celebrity represented a modern force that clashed with traditionalism, resulting in a common saying among mainlanders: “Deng Xiaoping by day, Teresa Teng by night.” Jia also overlays the sound of Hong Kong action films in the auditory background of Xiao Wu, reminding viewers that mainland China had already been influenced by cultural imports from Hong Kong and Taiwan. This constant dialectic between the modern and traditional situates Jia’s cinema as the work of an outsider, neither conforming to tradition nor fully denying its influence on his work. Eventually, his films would break from the Sixth Generation label and its perceived artistic characteristics.

While studying at the BFA, Jia read the criticism and theoretical writing of André Bazin, co-founder of the Cahiers du cinéma and champion of realism—in particular, the Italian Neorealism of the 1940s and 1950s that also inspired the French New Wave. Just as Italy faced a volatile period after World War II, with political and economic chaos leaving thousands of everyday citizens jobless and struggling to survive, Jia’s contemporary China faced comparable problems such as crime, unemployment, poverty, and displaced populations. However, this drive toward realism, particularly among Italian filmmakers, gave way to poetic flourishes. Whereas Bazin argues for the “ontology of the photographic image” as a testament to cinematic realism, Jia scholar Cecília Mello calls realism a “malleable concept”—a generous description for all manner of poetic license. This ranges from a filmmaker’s choice of subject matter to how narrative content is captured, edited, and presented through various cinematic apparatuses, each requiring a filmworker’s artistic touch. The usual methods of realism—observational perspectives captured in long takes, handheld camerawork, nonprofessional performers, real-life spaces, and natural light—remain a filmmaker’s stylistic methods of conveying meaning. Realism is not an absence of style but, like any stylistic accent, used to impart an intended feeling or impression.

Jia is not purely a realist; neither were the Italian Neorealists. They both blend an articulation of reality with the poetics of artistic tradition—what Bazin called an “intermediality” where different forms of art collide. Writing in the Cahiers du cinéma in 2004, Jia remarked. “In the past, Chinese poets had the habit of composing poems on the road. In a similar vein, I very much love travelling, going to small towns or unknown villages.” Significantly, Jia associates himself not with a documentarian who observes the real world and conveys that to his audience; rather, he compares himself to a migrant poet. How fitting that Xiao Wu’s closest cinematic companion remains Bicycle Thieves (1948), De Sica’s Neorealist landmark. Both supply a portrait of a desperate individual who resorts to theft to survive, yet both contain a dramatic structure and visual touches that could be called poetic. Just as De Sica poeticizes his camerawork with far-from-realistic Dutch tilts, high-contrast shadows, and a harrowing tale of a father and son in conditions of poverty, Jia frames his protagonist as tragically out of step with the changes around him. As a child, Jia had seen Bicycle Thieves and later studied the film in a university world cinema course. “The Italian neorealists gave many of us the inspiration to turn our cameras to real people and experiences. We found ourselves borrowing a lot of their methods,” he wrote.

Even though the international film community has celebrated Jia’s films for their realism, his output often balances documentary-style observation with more expressive gestures. Watch any of Jia’s documentaries and notice that the filmmaker has taken artistic license. In his 2010 documentary I Wish I Knew, about the changes in Shanghai over the last century, he uses traditional interviews and archival footage. But his muse-turned-spouse Zhao Tao also wanders through modern-day Shanghai like a ghost, engaging in a subtle, expressive, vaguely dancelike performance that breaks from a purely observational approach to convey meaning. Similarly, Jia imbues his dramas with documentary filmmaking techniques, evidenced in how often he captures China’s change on camera. Still Life (2006), for instance, his story about people reconnecting after a long time apart, unfolds against the demolition of cities to make way for the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. But without drawing too much attention, his portrait of this transitional location includes brief moments of futuristic or otherworldly influence. Though grounded in patient observation, Still Life also boasts a UFO, a building that takes off into space, and an apocalyptic survey crew, suggesting that the present changes so fast that sometimes it seems like we have collided with the future.

Xiao Wu remains such an assured beginning to Jia’s career because he clearly articulates his career-long interplay between documentary and cinematic expression. Jia conceived his debut after he graduated from the BFA and returned home on a visit for the Spring Festival, celebrating the Chinese Lunar New Year. Although he had planned to shoot something else for his first feature—a romantic drama set in a single room over a single night—he saw the scope of the change while walking around Fenyang after his long absence and resolved to capture that transformation. The sites of his youth, a network of interconnected brick homes that had been around since the Ming Dynasty, were demolished and replaced with new ones. What also struck Jia was how this overhaul impacted major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai along with smaller cities like Fenyang. The people had changed, too. Jia told interviewer Dennis Zhou: “China’s rapid economic development had brought in a new set of values. Traditionally, people based their emotional ties on kinship, community, and morality, but now, money had become the critical regulating factor.” Jia became fascinated with how people redefined themselves to coincide with the world around them.

Determined to chart the disappearance of a way of life that would soon be extinct, he drew from his experiences as a teen whose friend group sometimes resorted to pickpocketing. The notion went against the usual bent of Chinese cinema that, to be approved by the censors, a film had to support national ideological beliefs. Filmed over 21 days on location in Fenyang, Xiao Wu established many techniques that Jia would further develop into signatures in the coming decades: the frequent use of long takes; static, observational compositions; and characters framed by windows and doorways to show their isolation within the surrounding infrastructure. Yet, certain aspects of the production remain distinct in his career, such as using handheld 16 mm celluloid. After Xiao Wu, Jia went on to shoot Platform (2000) and The World (2004) on 35 mm. Later, he deployed early digital cameras to make Unknown Pleasures (2002) and Still Life, enhancing the aura of realism in much the same way filmmakers such as Spike Lee (Bamboozled, 2000) and Danny Boyle (28 Days Later, 2002) used mini-DVs in the early 2000s to give their projects a vérité, home-video aesthetic. However, most films directed by Jia in the 2010s and 2020s feature digital or high-definition digital photography.

On Xiao Wu, Jia’s aesthetic still feels raw, having completed only one other project as a BFA student—Xiao Shan Going Home (1995), also starring Wang Hongwei, about a cook headed home from Beijing for the Spring Festival. Many of the shots on the streets of Fenyang for Xiao Wu feature passers-by looking at the camera. The director’s longtime cinematographer, Nelson Yu Lik-wai, who has shot over 17 short films and features with Jia, tried to alleviate this by using a conspicuous fake camera positioned elsewhere to distract onlookers from the real, more covert camera. Often following Xiao Wu through crowds and navigating the mobile 16 mm camera between throngs of people, the film captures busy streets filled with traffic, pedestrians, and the deafening blare of automobiles, radios, televisions, and loudspeakers announcing official state policies. At times, Jia maneuvers through the bustling city. Elsewhere, Fenyang almost seems abandoned, giving way to a sharp contrast that Mello calls the “dialectics of fastness and slowness.” Jia characterizes the ever-changing face of China against the comparatively measured pace of human drama. He also shows Xiao Wu’s implosion with a spiraling scene in a KTV bathed in red, recalling the chaotic bar sequences in Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973). Each choice leads to an intended feeling beyond mere realistic representation.

Xiao Wu’s nature as a wanderer through Fenyang meant his character could have random encounters with people, allowing Jia to chart the city’s evolution from the perspective of an observer who might border on a flaneur if not for his pickpocketing. The camera often adopts his perspective to consider the space, even as Jia uses his lead actor to convey the city’s fluctuating status, embodied by his edgy, restless mannerisms behind an armor of thick glasses and confident body language. Although the title takes the name of the film’s protagonist, the character can be passive and uncertain against the ever-moving world. Rather than a character study, Jia calls his film a “group portrait” of all classes and types, isolating those who can adapt to the times and those who cannot. The director told Dennis Zhou, “I have concluded that the people in my films all share a commonality: no matter what class they are, they are all powerless in a sense, that is, passive, controlled by the political and economic changes in the outside world. In China, this situation applies whether one is a boss or a thief, a person in a big city or a small town. We all share the same fate.”

To that end, the film ends with Xiao Wu captured by authorities and handcuffed to a telephone pole’s tension cable. Although, to this point, the character has been defined by his uneasy movement, his arrest renders him immobile, as though reflecting his role in the local culture. “Society prevails,” critic J. Hoberman observed in his 2021 assessment. This is presented as a tragic and almost nightmarish display of public humiliation, with the final shots from Xiao Wu’s perspective lasting over a minute. Passers-by stare at him curiously, the discomfort of the scene growing as a crowd gathers to see this human leftover of China’s reforms. Though their expressions do not necessarily convey shame, the feeling is nonetheless evoked—as though Xiao Wu were a freak show spectacle gawked at by onlookers. With this confronting final image, which articulates a society moving so fast that some cannot keep up, it’s no wonder China’s censorship board did not approve Jia’s film for mainland distribution. However, the film made the rounds on the international festival circuit, where it won the 1998 Berlin Film Festival’s Wolfgang Staudte Award and the best film prize at the San Francisco International Film Festival. It also marked the first part of Jia’s so-called Hometown Trilogy set in Fenyang, followed by Platform and Unknown Pleasures.

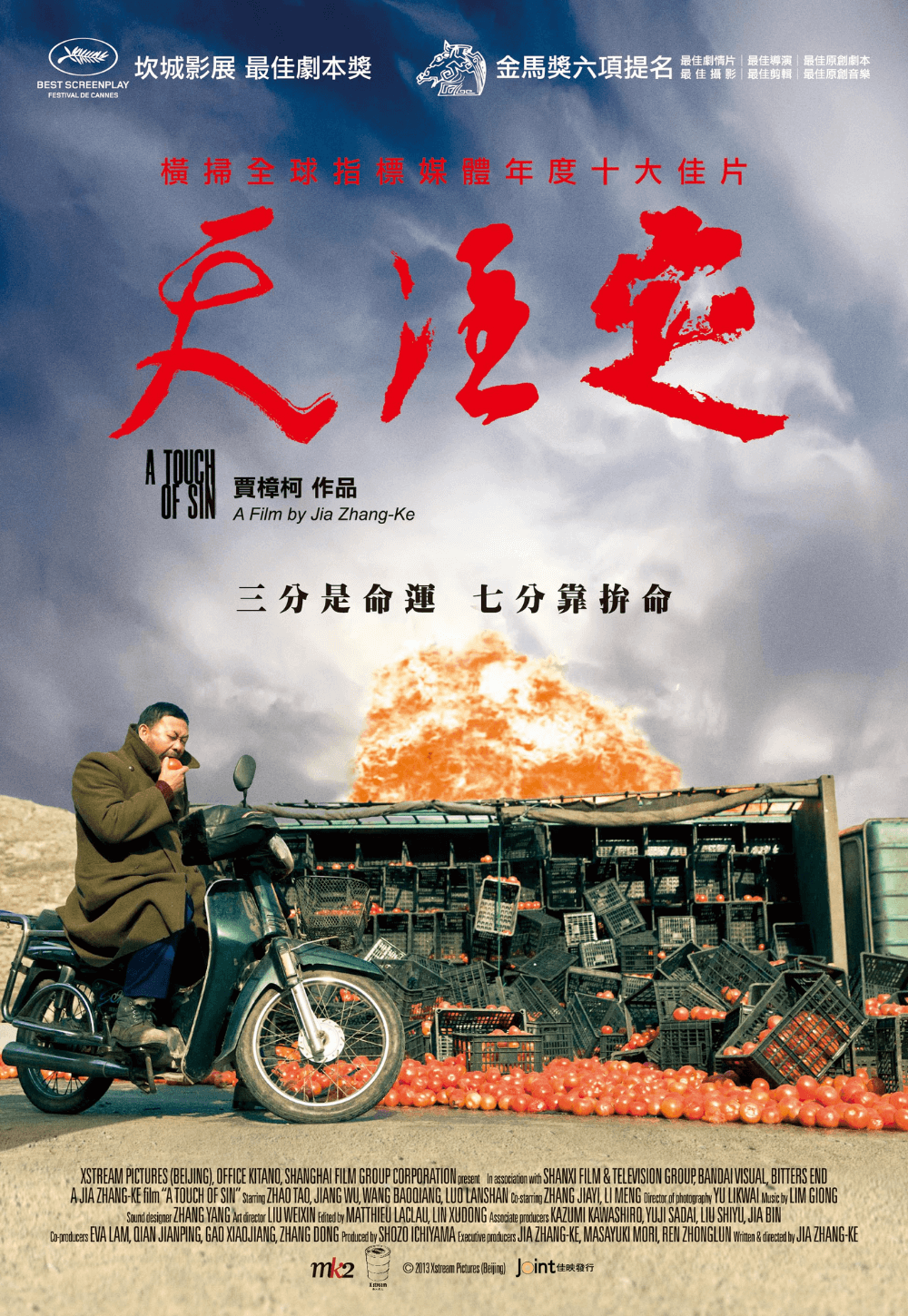

Cinema’s greatest artists, those who push the medium forward, often work in periods of radical cultural transformation. Neorealists and New Wave artists from countries such as Italy, France, and South Korea capture their transitioning world in formal and narrative parallels and contradictions. Jia Zhangke’s persistent interest in the degrading personal relationships and structures within China’s rampant post-socialist environment began with his debut. Xiao Wu launched his tendency to apply elliptical narratives and open-ended conclusions, where the forward thrust of the story remains less important than the film’s atmosphere of change and the implied human cost. Much later, Jia would embed these ideas into genre cinema, such as crime in A Touch of Sin (2013) and decades-sweeping dramas such as Mountains May Depart (2015) and Ash is Purest White (2018). But with his first film, he remains defiant in his formal and narrative observations, lending an aesthetic that—just as many neorealists around the world did—announced the beginning of a rebellious artistic movement that clashed with its culture. In the face of China’s accelerated expansion, Jia resolves to slow down, observe, and therein contradict the rapid changes around him. It is the expressive act of an insightful artist whose cinema attempts to seize a fluid moment in time.

(Note: This essay was originally posted to DFR’s Patreon on January 27, 2025.)

Bibliography:

Berry, Chris. “Xiao Wu: Watching Time Go By.” Chinese Films in Focus II. Chris Berry, editor. Palgrave Macmillian, 2008, pp. 250-257.

Berry, Michael. Jia Zhangke’s “Hometown Trilogy”: Xiao Wu, Platform, Unknown Pleasures. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Frodon, Jean-Michel. The World of Jia Zhangke. Film Desk Books, 2021.

Hoberman, J. “In ‘Xiao Wu,’ a Wandering Pickpocket in the People’s China.” The New York Times. 21 July 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/21/movies/xiao-wu-pickpocket.htm, Accessed 31 December 2024.

Jia, Zhangke, “The Joy and Pain of One Good Meal in Bicycle Thieves.” The Criterion Current. 18 March 2019. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6246-the-joy-and-pain-of-one-good-meal-in-bicycle-thieves. Accessed 10 January 2025.

Mello, Cecília. The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2019.

Wang, Xiaoping. China in the Age of Global Capitalism: Jia Zhangke’s Filmic World. Routledge; 1st edition, 2019.

Zhou, Dennis. “Jia Zhangke in Conversation with Dennis Zhou.” Metrograph. N.D. https://metrograph.com/jia-zhangke/?v=0b3b97fa6688. Accessed 5 January 2025.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review