The Definitives

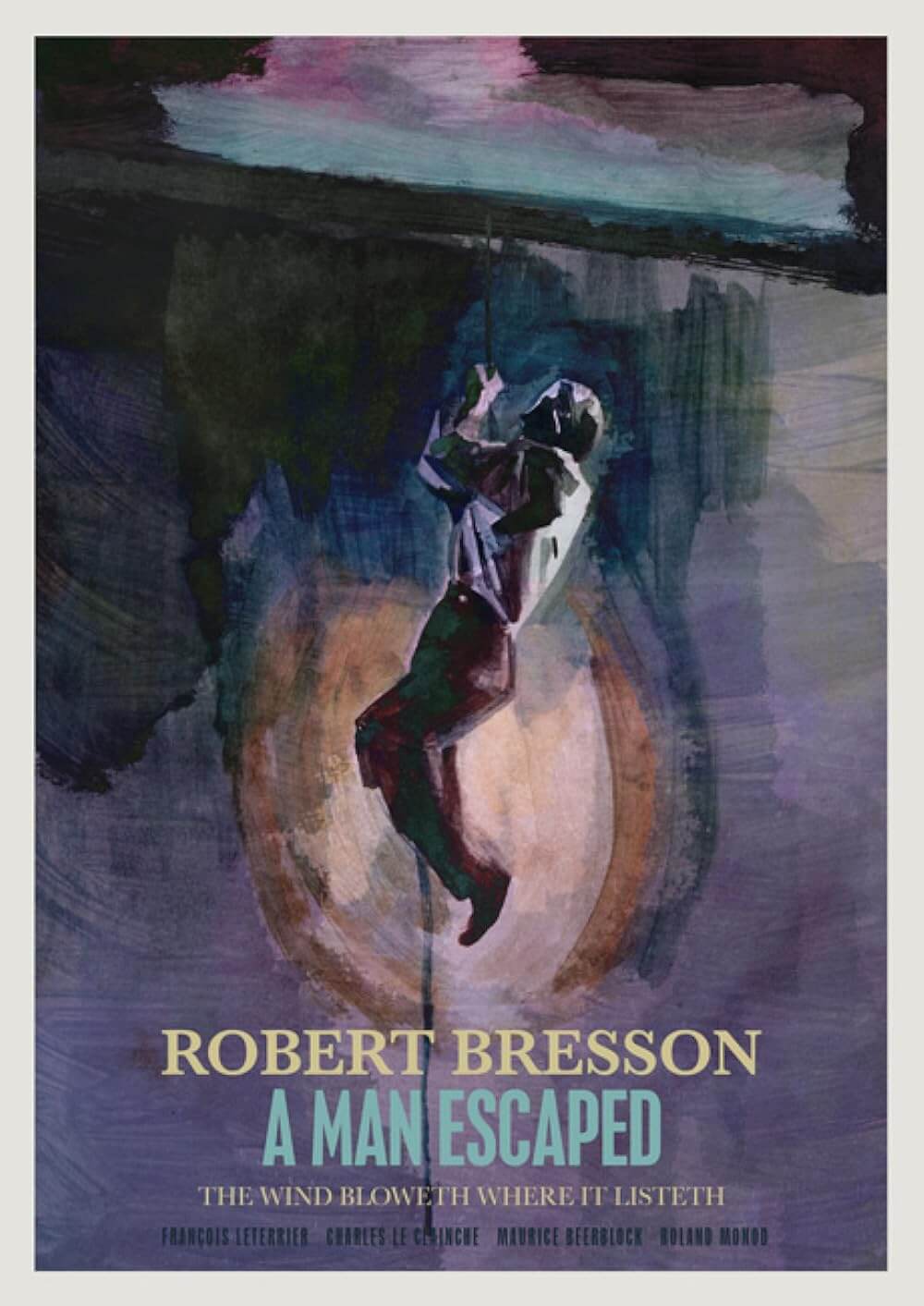

A Man Escaped

Essay by Brian Eggert |

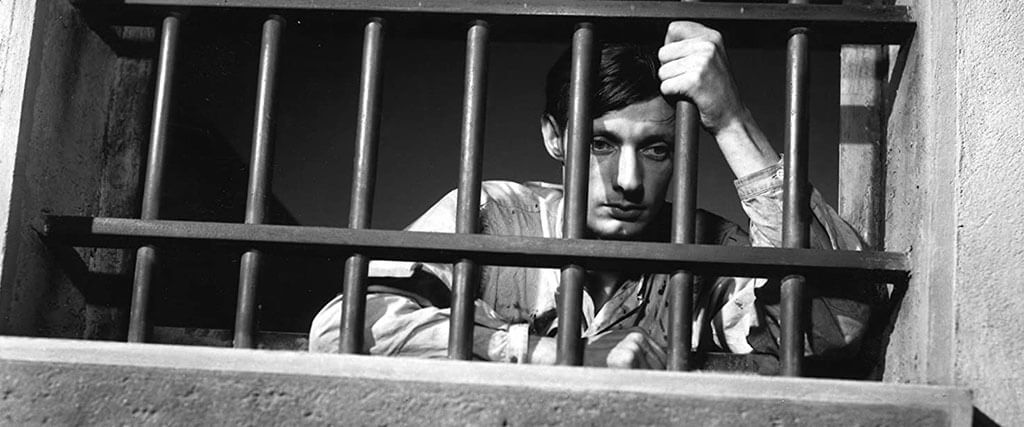

A Man Escaped opens with a close-up on a pair of hands resting on knees in the backseat of a moving car. They lift and rotate as though their owner examines them and ponders what they might accomplish. Reaching for the car door, the left hand considers turning the handle, but then hesitates. The shot pulls back to reveal Fontaine, played by François Leterrier, seated next to two other prisoners whose hands are cuffed together. Fate has been kind to Fontaine; his hands are uncuffed for the moment, and he will not be one of the 7,000 prisoners who died in Montluc prison during the Second World War. Throughout director Robert Bresson’s uncompromising prison break film, Fontaine’s hands will remain central to the action, guided by fate. They project more than Fontaine’s face, and they convey everything the viewer needs to know about the character’s attempted escape from a German prison in 1943. Bresson offers no establishing shot in this first scene, no context beyond the immediacy of the hands and what they hope to achieve; they remain the film’s subject and the means through which Fontaine achieves his salvation. This proves true of Bresson’s technique as well. A Man Escaped epitomizes how Bresson used action to achieve spiritual deliverance in his films. He depicts the escape with a focus on process, revealing himself as a filmmaker obsessed with distilling cinema to its purest form. At the same time, his unwavering devotion to the task at hand allows his character to free himself from prison and achieve a manner of transcendence.

Although Bresson’s career spanned four decades, from his 1943 debut Les Anges du péché to his final film, L’Argent, released in 1983, the French master made just thirteen films. Despite so few, Bresson became one of the most highly respected figures in French cinema because he maintained a single-minded commitment to his vision. Unlike his contemporaries—even Jean Renoir went to Hollywood at one point—Bresson never wavered from his rigid aesthetic, thematic preoccupations, religious underpinnings, and personal philosophy of filmmaking. Few directors remain so devoted to their cause, so unwilling to make commercial-minded compromises, making an auteur study of Bresson almost effortless. His faithfulness has been attributed to his worldview, gleaned from what little biographical evidence exists in his many interviews. There has never been a thorough study published about Bresson’s life, only analyses of his films, such as Joseph Cunneen’s Robert Bresson: A Spiritual Style in Film from 2003 and Tony Pipolo’s Robert Bresson: A Passion for Film from 2010. Nevertheless, using Bresson’s remarks and writings about his own work and the observations made by scholars entranced by his output, it becomes clear that A Man Escaped exemplifies the Bressonian style and approach more than his other most celebrated pictures, such as Diary of a Country Priest (1951), Pickpocket (1959), or Au hasard Balthazar (1966).

Perhaps the film so lucidly evokes Bresson’s aesthetic because he found the material personally relatable. In 1939 during the Second World War, Bresson spent a year in a German prison, and the experience left him traumatized by all accounts. However, his screenplay of A Man Escaped was based on a memoir by André Devigny, a French Army lieutenant who, after serving as an infantryman, joined the Resistance to fight the Nazis. In 1943, Devigny was captured by the Gestapo and sent to the inescapable Montluc Prison, from which he made several successful escapes only to be recaptured. Following the war, in 1954, Devigny published “The Lessons of Strength: A Man Condemned to Death Has Escaped,” a journalistic account of his flight from Montluc. Two years later, Devigny turned the article into a memoir titled, A Condemned Prisoner Has Escaped. Bresson was attracted to the initial article’s “very precise, even technical accounts,” calling it “a thing of great beauty” for its unadorned style. The director proceeded to write the screenplay and dialogue himself, and he enlisted Devigny as a technical advisor to ensure accuracy. The film, which debuted at the Cannes Film Festival in 1957 and earned Bresson an award for Best Director, opens with the promise, “I present it as it happened without adornment.”

Perhaps the film so lucidly evokes Bresson’s aesthetic because he found the material personally relatable. In 1939 during the Second World War, Bresson spent a year in a German prison, and the experience left him traumatized by all accounts. However, his screenplay of A Man Escaped was based on a memoir by André Devigny, a French Army lieutenant who, after serving as an infantryman, joined the Resistance to fight the Nazis. In 1943, Devigny was captured by the Gestapo and sent to the inescapable Montluc Prison, from which he made several successful escapes only to be recaptured. Following the war, in 1954, Devigny published “The Lessons of Strength: A Man Condemned to Death Has Escaped,” a journalistic account of his flight from Montluc. Two years later, Devigny turned the article into a memoir titled, A Condemned Prisoner Has Escaped. Bresson was attracted to the initial article’s “very precise, even technical accounts,” calling it “a thing of great beauty” for its unadorned style. The director proceeded to write the screenplay and dialogue himself, and he enlisted Devigny as a technical advisor to ensure accuracy. The film, which debuted at the Cannes Film Festival in 1957 and earned Bresson an award for Best Director, opens with the promise, “I present it as it happened without adornment.”

Thus, the story is lean and efficient, scraping away any artifice or pretense, just as the title indicates. Once he arrives in a Lyon prison, Fontaine remains committed to escaping not only from capture but a death sentence. After the first scene in which he tries to escape a moving car en route to the prison, he is beaten and cuffed. Fontaine soon promises the guards that he will not attempt to escape again, which secures him a spot on the top floor, where he quickly begins working his way toward freedom. Unlike other prison films, Fontaine does not form deep emotional bonds with his fellow prisoners outside of functional chatter, nor does he share intimate stories about his life before or during the war. The viewer’s insights into the protagonist’s mind come from his action and his voiceover, drawn from Devigny’s article, delivered in a flat tone. To be sure, the relationship that receives the most screen time in A Man Escaped exists between Fontaine and his wooden door, where he kneels to scratch away at the wood, attempting to remove three panels that will allow him to enter the corridor. Captured in painstaking and methodical detail, Fontaine loosens the door’s panels by carving with a makeshift chisel made from a spoon; he also fashions rope from materials on his bed and a hook from a lantern frame. In the end, he and a cellmate, Jost (Charles Le Clainche), will pass through the hole in their cell door, climb onto the roof, pass over an outer wall, and shimmy their way to freedom.

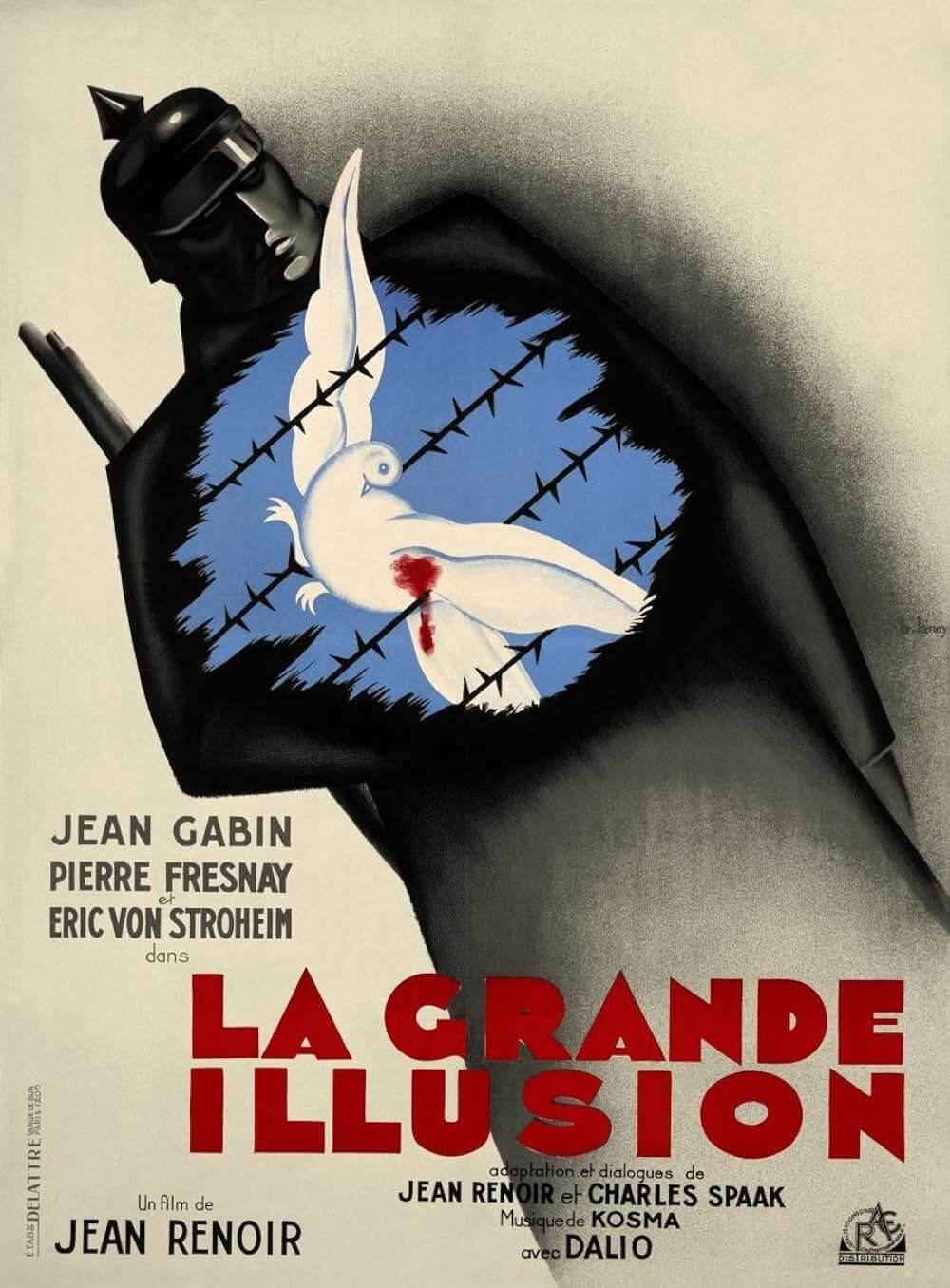

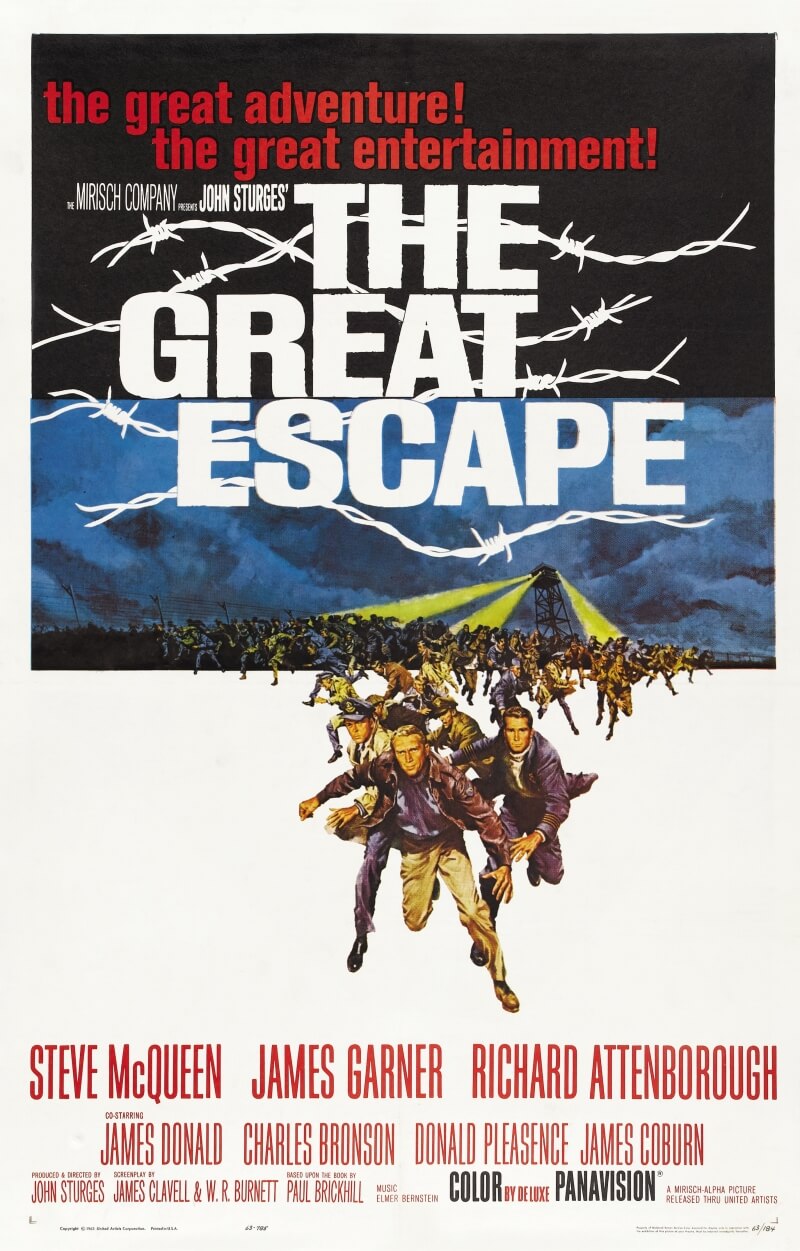

Audiences have seen similar stories countless times, especially in the years following the Second World War. Prison breaks supply a necessary catharsis, whether they reflect our desire for freedom and spirit of rebellion in particularly restrictive times, create heroic wartime fantasies about POWs thwarting their captors, or simply capture the pleasure of process. Titles from The Great Escape (1963) to The Shawshank Redemption (1994) resonate beyond their particular time and place to evoke the viewer’s desire for spiritual liberation. Even in French cinema, the prison break genre has been thoroughly explored from Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1937) to Jacques Becker’s Le Trou (1960), and in each case, the escape represents something greater than the task itself. Bresson takes a different approach with A Man Escaped; he minimizes the dramatic embellishments and usual sprawling cast of characters found in the prison break film, simmering the filmmaking and narrative into a fine reduction. Its French title, Un Condamné à Mort s’est Échappé, literally “A Death Row Inmate Escaped,” pares down what later filmmakers would adorn and overstate. Some critics, such as Susan Sontag who wrote, “Bresson seems to have left out too much,” claimed Bresson’s approach lacks humanity. From another perspective, Bresson’s focus on action reflects his worldview that our behaviors echo our inner selves, and he points the cinematic apparatus in that direction, no other.

Bresson’s unvarying control over every formal aspect of his productions—from his selection of actor-types to the image, and the music—makes him unique among his contemporaries. A Man Escaped was only his fourth film, and his first three works seem to build toward its austerity, its unity of form and function. While other filmmakers make compromises to studio demands or at the insistence of their artistic collaborators, Bresson was the truest of auteurs who left nothing to chance, nothing up to the egos of his actors, nothing to the whims of his cinematographer, and nothing to his distributors to reshape in their vision. With A Man Escaped, Bresson’s screenplay serves his interest in physical action, unifying his belief that the cinematic apparatus could be refined to achieve a profound sense of spiritual understanding. His book on this approach, Notes sur le cinématographe (Notes on the Cinematograph), published in 1975, established his belief in a distinction between what is generally called “cinema” as a form of dramatized theater captured on film and what he called “cinematography,” which relies on a precise unity of image and sound, a type of “pure cinema” that moves away from the drama of commercial cinema and into a transcendent form of art.

Bresson’s unvarying control over every formal aspect of his productions—from his selection of actor-types to the image, and the music—makes him unique among his contemporaries. A Man Escaped was only his fourth film, and his first three works seem to build toward its austerity, its unity of form and function. While other filmmakers make compromises to studio demands or at the insistence of their artistic collaborators, Bresson was the truest of auteurs who left nothing to chance, nothing up to the egos of his actors, nothing to the whims of his cinematographer, and nothing to his distributors to reshape in their vision. With A Man Escaped, Bresson’s screenplay serves his interest in physical action, unifying his belief that the cinematic apparatus could be refined to achieve a profound sense of spiritual understanding. His book on this approach, Notes sur le cinématographe (Notes on the Cinematograph), published in 1975, established his belief in a distinction between what is generally called “cinema” as a form of dramatized theater captured on film and what he called “cinematography,” which relies on a precise unity of image and sound, a type of “pure cinema” that moves away from the drama of commercial cinema and into a transcendent form of art.

To better appreciate how A Man Escaped‘s simple story creates a veritable religious experience for Bresson, we must consider his formal techniques. In a 1955 interview with L’Institution des Hautes Études Cinématographiques, Bresson talked about creating “rapports” between each element of his films. The script; the look of actors, the sound of their voice, and their performance; the sets, props, and costumes; the camerawork, angles, blocking, and lighting. All of these had to relate to each other in a meaningful unison, and every element of the production receives the same amount of attention from Bresson. He labors so that each aspect presents the action’s progress with clarity, conveying the connection between one moment to the next. Bresson’s refined aesthetic resisted many of the expressions found in commercial filmmaking: he offers no recognizable stars to ornament or divert from the film’s purpose, no showy mise-en-scène or self-indulgent camerawork, and minimal dialogue apart from voiceover—albeit without the searching and existential ennui found in voiceover by other European arthouse directors like Ingmar Bergman or Michelangelo Antonioni. Bresson is not interested in internalizations or outpourings of emotions but rather signifying emotion through action in what Pipolo called “de-theatricalizing” film into a focused, almost utilitarian project. Even Fontaine’s voiceover resists the poetry of narration often found in French cinema at this time; rather, it proves almost superfluous, simply narrating the action as it unfolds onscreen.

Given his desire to create rapports, the editing style cannot be called montage in the Soviet sense, where the viewer makes unconscious associations from the relationship between two shots, nor does it represent the invisible continuity editing desired by Hollywood’s predominant interest in character and drama. Bresson’s style puts action first, laying it out with a shot-for-shot logic that gives greater understanding to the advancement of a task. Take the sequence when Fontaine uses two spoons to loosen the boards on his door. It starts when he approaches the door. In the next shot, we see the spoons put into place, and Fontaine begins to bend them, but the wood creaks. Then we see Fontaine in close-up as he hesitates, followed by a first-person perspective shot as Fontaine looks through the peephole to see if anyone approaches. Cleared, he bends the spoons further. A shot of his face shows his exertion. Bresson cuts to the wood breaking, then another shot of a wood piece falling to the floor. The editing is neither invisible nor based on emotional interpretation; the progression is calculating, visible, and unmistakable. As Sontag observed, “Nothing happens by chance; there are no alternatives, no fantasy; everything is inexorable. Whatever is not necessary, whatever is merely anecdotal or decorative, must be left out.”

Bresson shoots the action in A Man Escaped without affectation. Each shot is edited to emphasize an individual action and build to the next, making every cut a logical progression and the shot duration calibrated to support the action. No single shot, save for the last image of Fontaine and Jost escaping into the night, delivers closure, only the next step in the progression. No shot deviates or provides an aside. A Man Escaped is devoid of unnecessary subplots or randomness; its focus is a forward narrative thrust, an unshakable momentum toward the protagonist’s desired outcome. Even in two-shot conversations between Fontaine and Jost, the scene’s function is not character development or establishing atmosphere but determining whether Fontaine must bring Jost along or kill him for knowing the plan. Just as the camera’s objectivity keeps a measured distance to portray the action with clarity, the action reflects Fontaine himself—single-minded, focused on his goal, undeterred by memories or thoughts of the outside world. We learn everything we need to know about him by watching him carry out his mission to escape. “Action is character,” as Pipolo has noted more than once.

Bresson shoots the action in A Man Escaped without affectation. Each shot is edited to emphasize an individual action and build to the next, making every cut a logical progression and the shot duration calibrated to support the action. No single shot, save for the last image of Fontaine and Jost escaping into the night, delivers closure, only the next step in the progression. No shot deviates or provides an aside. A Man Escaped is devoid of unnecessary subplots or randomness; its focus is a forward narrative thrust, an unshakable momentum toward the protagonist’s desired outcome. Even in two-shot conversations between Fontaine and Jost, the scene’s function is not character development or establishing atmosphere but determining whether Fontaine must bring Jost along or kill him for knowing the plan. Just as the camera’s objectivity keeps a measured distance to portray the action with clarity, the action reflects Fontaine himself—single-minded, focused on his goal, undeterred by memories or thoughts of the outside world. We learn everything we need to know about him by watching him carry out his mission to escape. “Action is character,” as Pipolo has noted more than once.

Defining character through action as he does, Bresson resisted actors. He called his performers “models”—an idea that Pipolo suggests derives from Bresson’s early years as a failed painter. In this sense, Bresson’s actors are sitting for a portrait of their character, which Bresson captures through his direction of rapports. Bresson felt the problem with actors is how they perform. He hoped to eliminate the artificiality of performance and get the essence of action by removing the focus from the actor’s face, allowing the viewer to concentrate on film form and the represented action rather than the actor’s interpretation of it. He vigorously opposed the indulgences of acting and how performers encouraged the audience to “search for the talent on his or her face,” a quality that distracts from the harmony of rapports. To avoid this, Bresson, like Stanley Kubrick or David Fincher, was known to break down his actors with upwards of fifty takes of a scene. After repeating a scene ad nauseam, the performer would eventually reduce the action to its purest form, stripping down a character to their basic gestures to reinforce the notion that action replaces any need to explore the internal character. Through this process, Bresson uses inexperienced performers, allowing him to mold the character as a sculptor does clay. For instance, Leterrier was a philosophy student, and A Man Escaped would be his first of only two screen appearances. We watch Leterrier in the film with no extratextual associations or assumptions about the “Leterrier persona” (as we might associate certain characteristics with actors like Jean Gabin or Robert De Niro). We know only what we see, captured in Bresson’s almost exclusively medium shots that focus on action, avoiding close-ups that depend on the actor to emote. Rather, Bresson’s close-ups serve to give us visual detail of Fontaine’s hands fashioning homemade rope or scraping away at his door with his makeshift chisel.

Bresson’s spare and unadorned style also plays into the film’s spiritual meaning, signaled by its alternate title, The Wind Blows Where It Will—a reference to John 3:8, meaning that only by opening oneself up to God will one be imbued with the Holy Spirit, or “Wind,” and receive a manner of absolution or rebirth. By the time A Man Escaped was released, Bresson had been associated with religious cinema. He studied Catholicism in the first half of his life, and his films would contain religious themes well after his 1956 release, some overt, some subtextual. His debut, Les Anges du péché (The Angels of Sin), follows a novitiate nun’s attempt to save a killer’s soul; his third film, Diary of a Country Priest (1951), details a young clergyman’s struggle to reconcile his religious idealism with the insouciance of those around him; Au hasard Balthazar follows the life of a Christlike donkey who endures the sins and tortures, and occasional love, of the various people he encounters. Despite Bresson’s concentration on action in A Man Escaped, the religious theme suggests that something miraculous happens to Fontaine inside the prison—that fate, the hand of God, orchestrates everything that happens because Fontaine trusts in God, and this ultimately allows the protagonist to carry out his escape—a kind of spiritual transcendence.

After all, Fontaine has no master plan. There is never an expository scene where the protagonist outlines what comes after he removes the door’s three panels, at which point he can search the corridors for his next move. His progress is a matter of faith that another opportunity will present itself. He continues to make rope—removing and straightening wire from his bed, slicing his pillow into thin strips, folding them into stronger pieces, and wrapping them together with the straightened wire into a durable bind—even though he doesn’t know exactly how it will be used. Fontaine’s escape attempt is an act of trust that God will save him from the death sentence passed by the Gestapo, and his focus on work allows the character to defy his captors. Alternatively, in his book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, Paul Schrader argues that Bresson “knows exactly” how his films symbolize the transformative outcome for the soul through endurance. Bresson believed that God compelled artistic creation, and the artist was a kind of spiritual vessel, but Schrader notes the foresight required for Bresson to write, plan, and execute a film of such refinement. The association reinforces a Catholic logic that implies suffering is the natural Christlike path to salvation, death, and the soul’s inevitable journey from the body into eternal life.

After all, Fontaine has no master plan. There is never an expository scene where the protagonist outlines what comes after he removes the door’s three panels, at which point he can search the corridors for his next move. His progress is a matter of faith that another opportunity will present itself. He continues to make rope—removing and straightening wire from his bed, slicing his pillow into thin strips, folding them into stronger pieces, and wrapping them together with the straightened wire into a durable bind—even though he doesn’t know exactly how it will be used. Fontaine’s escape attempt is an act of trust that God will save him from the death sentence passed by the Gestapo, and his focus on work allows the character to defy his captors. Alternatively, in his book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, Paul Schrader argues that Bresson “knows exactly” how his films symbolize the transformative outcome for the soul through endurance. Bresson believed that God compelled artistic creation, and the artist was a kind of spiritual vessel, but Schrader notes the foresight required for Bresson to write, plan, and execute a film of such refinement. The association reinforces a Catholic logic that implies suffering is the natural Christlike path to salvation, death, and the soul’s inevitable journey from the body into eternal life.

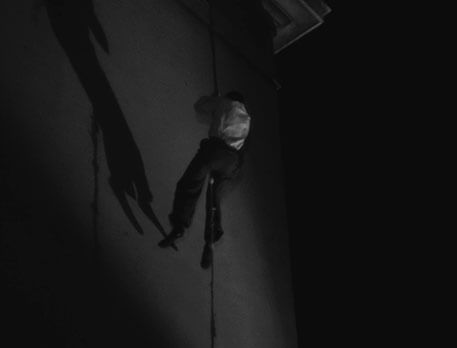

The final escape sequence lasts eighteen minutes. It’s a masterful display of tension, deliberate action, and sound design. Bresson accentuates sound effects throughout the film, but during the escape, sound effects—Fontaine and Jost’s footsteps on the gravel, a passing train, and the clock tower bell—serve as deafening intrusions on their progress. When they finally scale the last wall and disappear into the night fog to their freedom, the screen fades to black. Bresson holds the blackness for over a minute, allowing an orchestra’s performance of Mozart’s Mass in C-Minor, specifically the section performed over the Kyrie—the initial sung prayer of a mass, a gesture of thanking God for his mercy—to capture the emotional height of their transcendence both in dramatic and spiritual terms. In reality, Devigny and his cellmate, Gimenez, escaped and Devigny missed his execution by three days; however, evidence suggests Gimenez was recaptured, tortured, and killed by the Gestapo. Bresson conveniently avoids this part of the actual story, offering instead an inspiring conclusion in which the viewer feels elevated by the hero’s escape and the music’s resonance.

When it was released, François Truffaut declared A Man Escaped “the most important film of the last ten years.” Truffaut and other Cahiers du Cinéma critics recognized and celebrated Bresson’s iconoclastic style that deviated from the “Tradition of Quality” in mainstream French cinema, which the New Wave would rally against in the years to come. Although Bresson used untrained actors and realism, just as Truffaut and others would in films like The 400 Blows (1959) and Breathless (1960), his style is entirely separate from their movement or any other movement. It can only be called Bressonian. Even within Bresson’s body of work, A Man Escaped is exceptional. No other film in his career has the same harmony of action, story, personal significance, formal intention, meaning, and spirituality. Bresson believed that art is an act of blind faith in creation. “His hand leads him on,” Bresson said of someone who creates, “helping him to continue and his state of grace, too, helps him continue.” Ironically, it’s through precision, control, and a detailed vision of how everything will come together that Bresson achieved such a superb film.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your recommendation and continued support, Martha!)

Bibliography:

Bresson, Mylene, editor. Bresson on Bresson: Interviews, 1943-1983. New York Review Books, 2016.

Bresson, Robert. Notes on the Cinematograph. New York Review Books, 2016.

Cunneen, Joseph. Robert Bresson: A Spiritual Style in Film. Continuum, 2003.

Pipolo, Tony. Robert Bresson: A Passion for Film. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Schrader, Paul. Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. University of California Press, 2018.

Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation and Other Essays. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review