The Definitives

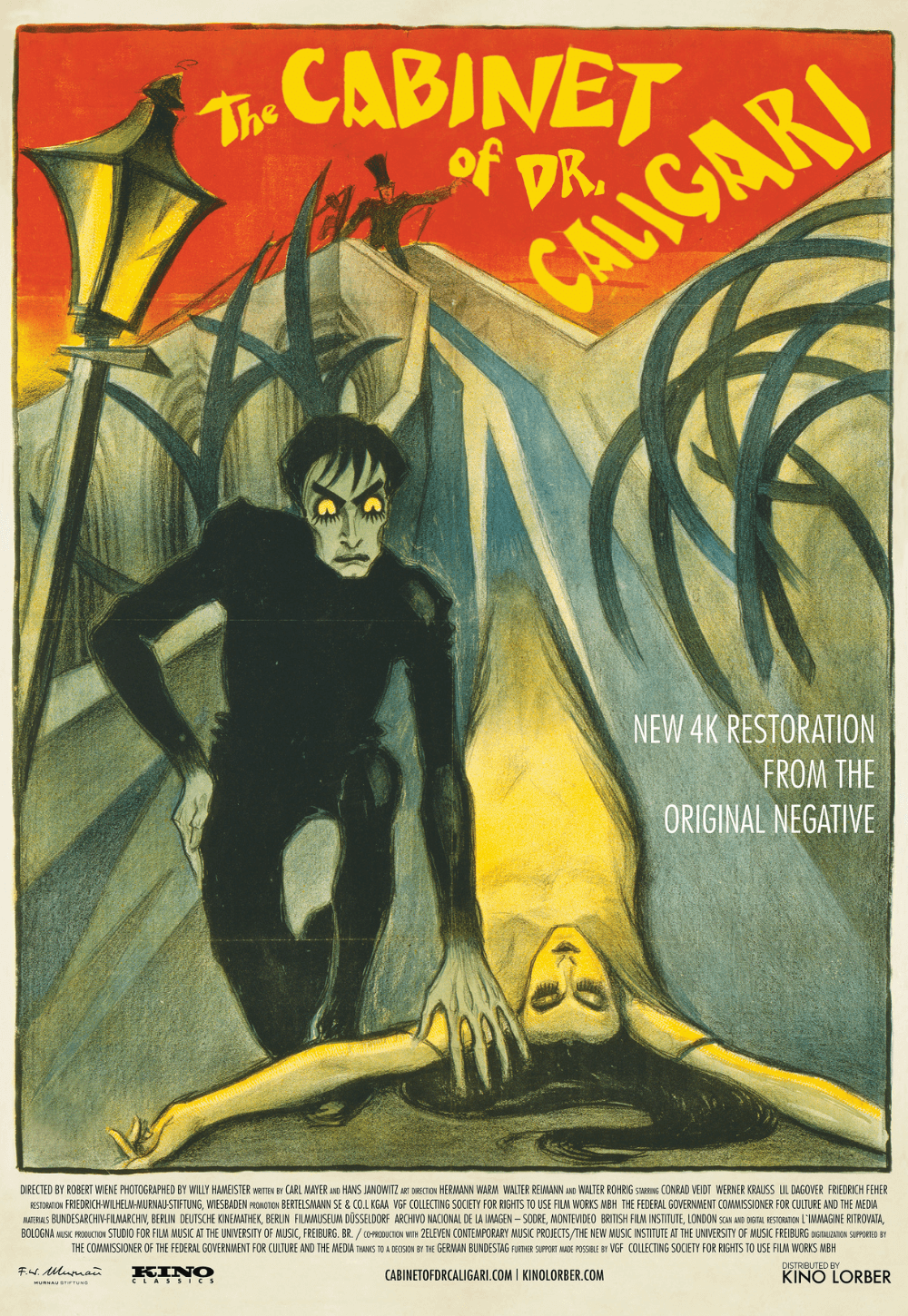

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari) is a landmark of macabre horror, propelled by madness, nightmarish visuals, and a fractured sense of self. To watch the film is to see the instant a cinematic movement was introduced to the world and began to change what films could do and how they looked. German Expressionism received its start in the medium here, establishing The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (hereon Caligari) as a significant paradigmatic shift in both the silent era and German cinema. By blending artistic intention and commercial ambition, the 1920 feature represents a tenuous harmony between the two polar modes of cinema that often remain at odds. As gothic fiction, it weaves a tragic love story with a brooding atmosphere and psychological terror, portraying isolation, insanity, and a corrupt authority figure who manipulates and murders through hypnotism. When this tale culminates in a shocking conclusion—a twist that still manages to upend expectations and astonish—it’s unshakable. Whereas many silent films devolve into historical artifacts or products of their time, enduring questions about what is real and imaginary in Caligari, along with extratextual questions about its production and authorship, persist with unsolvable yet fascinating equivocation. These facets conspire to make the film a timeless work of art and entertainment, vital for historical study, but perhaps more essentially, urgently watchable and accessible more than a century later.

Caligari has been central to many scholarly and critical debates since its release. Some have argued that the film’s landmark status in German Expressionism elevates the picture beyond the limits of commercial cinema and into the stratum of high art, if not experimental cinema. Others have deemed the subject matter and treatment of the narrative as rather lowbrow, resolving that it’s no more of a museum piece than any other commercial film. Regardless of its categorization, its influence remains unquestionable. Most historians agree that its innovations make it among the first and most foundational German Expressionist films, inspiring directors such as F. W. Murnau (Nosferatu, 1922), Fritz Lang (Metropolis, 1927), Alfred Hitchcock (The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog, 1927), and G.W. Pabst (Pandora’s Box, 1929). Given its imprint on cinema, many have debated who deserves credit for the result, most attributing the outcome to screenwriters Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz or director Robert Wiene. Others focus on the film’s narrative structure and meaning, questioning whether it’s a yarn spun by a deceptive madman narrator or an uncanny portrait of how authority abuses its power. These ongoing and unresolvable debates keep Caligari from dissolving into a mere case study and maintain its power to intrigue, confound, fascinate, and inspire.

Consider first the question of authorship. For much of the twentieth century, Siegfried Kracauer’s 1947 book, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, was considered the archetypal text for understanding the origins and artistic motivations behind Caligari’s production. Janowitz, one of the only significant creatives involved in the filmmaking process to document its production in any detail, took credit along with Mayer for the film’s creation and innovations in an unpublished 1941 document called “Caligari: The Story of a Famous Story.” This document supplied Kracauer with the evidence needed for his foundational book. Subsequent scholars such as Kristin Thompson, David Robinson, and David B. Pratt have since debunked many of Janowitz’s assertions established in Kracauer’s text, which were then echoed in the many later books and scholarly essays that expanded upon his claims. However, in the 1990s, a copy of the original shooting script revealed that director Robert Wiene—often sidelined in discussions of Caligari’s artistic input given his death from cancer in 1938, leaving the story of his film to be told by other people involved in the film’s production, who usually claimed more credit than they were due—had more influence than previously believed. Given his relatively modest filmography, his efforts are often dismissed next to those who survived the World War II era and could comment on the film’s production.

What becomes apparent after reading the fount of scholarship and conflicting evidence about Caligari is that, despite best attempts to attribute its creative vision to one source—the writers, the directors, etc.—the film is, unsurprisingly, the product of artistic fusion. Too often, writers, this one included, attribute a film’s artistic merits to the influence of a singular creative. Ever since writers in France’s Cahiers du cinéma championed the director as the author of a film, and Andrew Sarris later coined the term “auteur theory,” many scholars have sought the tidier explanation that one person remains the creative force behind the best films. Certainly, there are cases where this is true or mostly true. In other cases, great cinema springs out of chaos, happenstance, and collaboration—an alchemy of influences that combine into artistic harmony. Caligari belongs in that category. While Janowitz and Mayer provided the foundation with the script, producers Rudolf Meinert and Erich Pommer assembled a team of designers headed by Hermann Warm to craft the film’s painterly appearance, a notion championed by Wiene, who directed actors Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, Friedrich Feher, and Lil Dagover to bring the characters to life. If director Fritz Lang is to be believed, he was initially assigned to the project and contributed some key ideas; though, his anecdotes usually prove exaggerated or entirely false. By contrast, evidence shows that Wiene was instrumental in shaping the final film.

The screen scenario originated with Janowitz and Mayer, who met in 1918. Janowitz’s background was in fiction and theater criticism, and he had served in the Austrian army during The Great War, instilling a hatred for war that prompted him to contribute to left-wing magazines. Mayer had a similar background in theater and spent his war years combating a psychiatrist who was convinced Mayer was “mentally deranged” and “criminally insane,” according to Janowitz. Then again, Mayer may have been acting to avoid military service, prompting a false diagnosis. Either way, Mayer’s psychiatrist would become the spark of inspiration for Dr. Caligari, whereas Gilda Langer, an actress with whom Mayer was in love and who encouraged the two writers to collaborate, would become the inspiration for the film’s female lead, Jane. Besides the war—what Janowitz described as an example of “the authoritative power of an inhuman state gone mad”—the writers had experienced no end of misery, including Langer’s premature death. Janowitz also drew from his hometown in Prague and a disturbing close encounter with a murderer in 1913. At an amusement park on the Reeperbahn, a street in Hamburg that’s long been home to entertainment and the red-light district, Janowitz witnessed a blithely drunk young woman disappear in the bushes, only for a nondescript middle-class man to emerge some time later. The next day, Janowitz learned the woman had been slain.

These influences, along with a hypnotism act the writers had seen together in Berlin, merged into their script. They intended to write a film that would be an indictment of authority figures who use their positions of power to manipulate others to satisfy their personal desires. After six weeks of writing, the two approached Erich Pommer with their script. Pommer’s company Decla-Film had made pictures with Fritz Lang, Otto Rippert, and Victor Sjöström. The executive was impressed with how “the mysterious and macabre quality of Grand Guignol was in vogue in German films at that time, and this story was perfectly full of it.” He hired them on the spot. Pommer then enlisted Lang to direct, but he quickly removed him to finish work on the second part of The Spiders (Die Spinnen, 1919). Wiene took over, having already proven himself on fantastical material such as the script of F.W. Murnau’s lost film Satan (Satanas, 1920) and his own directorial effort, Fear (Furcht, 1917). The production of Caligari was considered cheap in Pommer’s view, requiring no considerable investment of financial capital or time on his part. Caligari was essentially a “B” production, before Hollywood studios adopted the term to describe their second-tier releases, and the story has all the qualities of such a programmer.

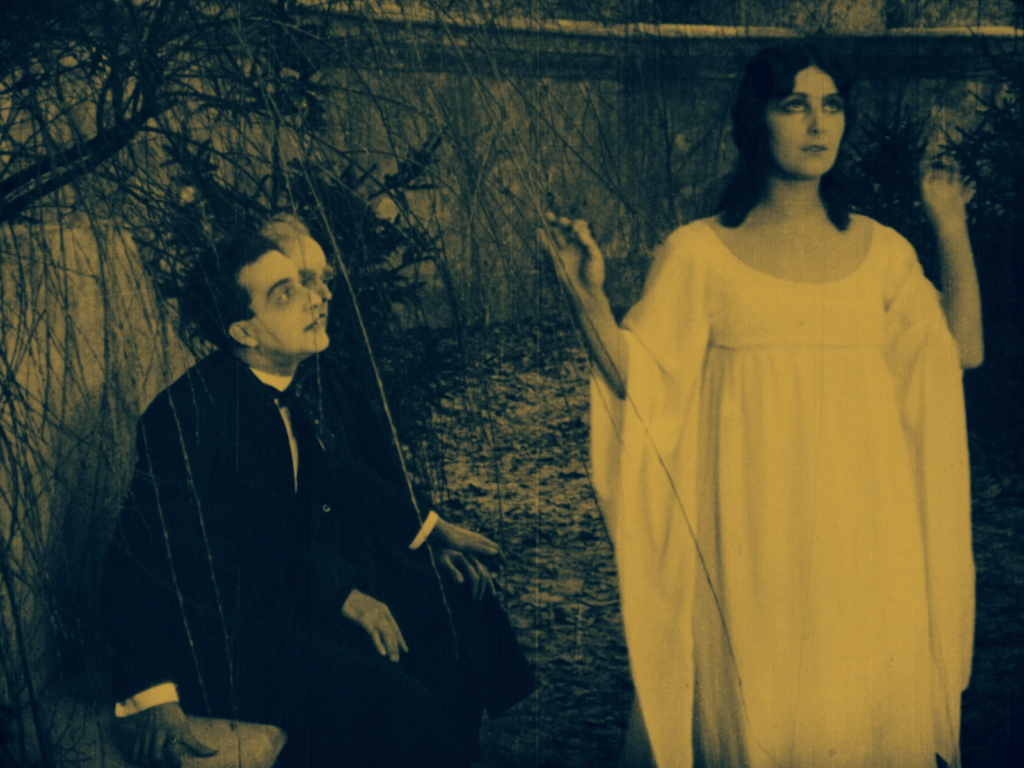

In a bookend framing device, Francis (Friedrich Feher) shares his account of a mysterious traveling performer, Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss), who arrives at his hometown carnival with a unique spectacle—a somnambulist named Cesare (Conrad Veidt), who has been asleep for his 23 years of life, and whom Caligari keeps in a coffin-like cabinet. Caligari claims that only he can awaken Cesare from his perpetual trance-like sleep. During one performance, the mystic announces that Cesare can predict the future. He invites the crowd to pose any question to Cesare. Francis’ friend, Alan (Hans Heinrich von Twardowski), asks, “How long will I live?” Cesare’s answer—“‘Till the break of dawn”—proves chilling, given a recent series of killings in the town, including a city clerk who insulted Caligari. However, Cesare is less a prognosticator than a living weapon under his master’s control, with Caligari using his mesmeric powers to command Cesare to do his bidding. When Alan is murdered that night, Francis teams with Dr. Olsen (Rudolf Lettinger), the father of his would-be sweetheart, Jane (Lil Dagover), to investigate Alan’s death and the somnambulist.

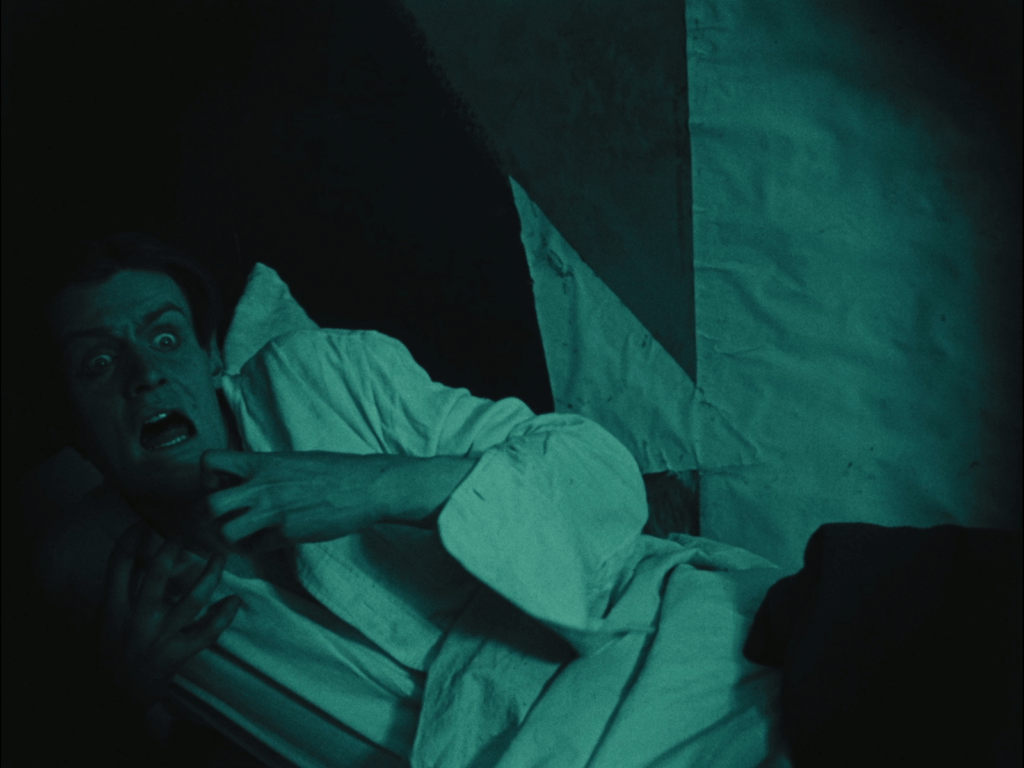

What they uncover is that the real Dr. Caligari operated in the early eighteenth century and sought to prove that a somnambulist could be compelled to commit murder. The man posing as Dr. Caligari is the director of the local insane asylum, who fixates on the former hypnotist (“I must become Caligari!”) and abuses his power in a demented experiment. Aware that he’s a suspect, the director sends Cesare to Jane’s bedroom at night, but rather than stabbing her, the somnambulist kidnaps her. The incident draws a crowd that prompts Cesare to drop Jane and flee, running until his sudden death. In the fracas, the so-called Caligari escapes, having delayed authorities by suggesting the Cesare in his cabinet was merely a dummy. Francis follows and, before long, joins the authorities to confront the asylum director with Cesare’s body. The director’s frenzied reaction lands him in a straitjacket, and order is seemingly restored. Back in the present, Francis ends his account. But then the film reveals his residence in the insane asylum—the characters from his story, including Jane and Cesare, are fellow patients. The figure Francis described as Dr. Caligari is the asylum director. Yet, Francis maniacally insists, “You all think that I’m insane! It isn’t true—it’s the director who’s insane!!” With this, the director orders Francis to be restrained and vows to cure him.

Janowitz and Mayer’s initial script did not include the framing device and twist ending. After the film’s release, the writers protested these additions—sometimes attributed to Lang, sometimes to Wiene—believing them detrimental to their critique of innately corrupt figures of authority. Kracauer agreed that the framing device distorted Janowitz and Mayer’s intent. Kracauer argued that the new ending promoted by Wiene “glorified authority,” inferring the opposite of the intended meaning. “A revolutionary film was thus turned into a conformist one,” he wrote. However, this interpretation negates the very real possibility that Francis is not a madman, a notion argued by scholar Mike Budd and others. Consider instead that Francis has been wrongly detained and so convincingly made into a lunatic by Dr. Caligari that he no longer resembles his former self. His raving sounds like the false testimony of a hallucinatory mental patient, but this is only because Dr. Caligari has so convincingly made him appear this way—a detail that may align with Mayer’s experiences with a doctor during the war. Alternatively, if the entire narrative is the delusion of the crazed Francis, it does not negate the notion that the authority Janowitz and Mayer sought to discredit has made little apparent progress in curing Francis. The authority presides over an asylum where patients run wild, acting as custodians more than doctors, which represents a censure of authority that Janowitz and Mayer had not considered.

Where the argument that the entire story is Francis’ fantasy begins to crumble are the scenes where Francis could not have been present, such as scenes that feature Alan or Dr. Caligari alone. These scenes suggest that the framing device of Francis telling the story, which Janowitz and Mayer detested so much, is less about establishing Francis’ perspective than a conventional literary technique to dramatize the events situated between typical bookends to underscore the beginning and end. After all, the acting styles and production designs of the asylum in the bookend scenes resemble those in the middle. Francis and the other patients have spooky black circles around their eyes and gesticulate in bold movements, just as they do in Francis’ supposed account. The asylum’s distinct patterned floor and sharply inclined stairways, too, adopt a similar expressiveness to the scenes relayed by Francis. Then again, it could be that the entire film is a presentation in that stylistic mode and that the exaggerated worldview does not belong solely to Francis but to the film’s commentary on the world—a distorted, corrupt place where authority figures prey on the vulnerable. On the other hand, the asylum setting does not appear to have the same graphical, hand-painted quality that most of the sets throughout the film do, suggesting that, while the whole film is stylized, only Francis’ account has been so graphically ornamented.

Those designs were the product of Warm, who read the script and immediately knew how to approach its aesthetic: “The film images had to be removed from reality, had to have a fantastic, graphic style.” He enlisted Walter Reimann, an experienced painter in the popular Expressionist style, along with Walter Röhrig, to help conceive the costumes, sets, and general décor. Headed by Warm, they pitched their ideas for the film’s look and feel to Meinert and Wiene. The producer believed the proposed stylistic experimentation would be a commercial feature beyond the story that would draw even more attention from the press and audiences than the story alone. The director instantly approved their designs and began annotating the script with notes that expanded on their ideas to achieve the desired visual sensationalism. This includes Wiene’s thoughtful removal of the modern touches Janowitz and Mayer included in their script, which initially took place around 1900. Any sign of electricity was replaced with an older appearance, giving the gothic setting a more fantastic, mythic feel. Even Reimann’s costumes seem to be from a long-ago age or from a period outside of time; many were original designs to enhance the story’s dreamlike quality. Years after the film’s release, after it had inspired so many others, Mayer came around to the filmmakers’ line of thinking regarding the application of Expressionist treatment and conceded that the film worked, whereas Janowitz remained unwavering in his objections.

How fitting, then, that Expressionism is less a definable style with attributable visual tropes or even an artistic school with devout members than a way to perceive the world. Its methods and the terminology used to describe Expressionism remain challenging to pinpoint, and descriptions of its specific characteristics often devolve into ambiguity. As a phenomenon emerging in the first quarter of the twentieth century, specifically in Germany, Expressionism in painting, literature, theater, and cinema was a projection of heightened emotional experiences, echoing the anxieties and existential dread over social and political turmoil in the years preceding and after The Great War. The mode was popularized in German-language literature by Ernst Toller, Walter Hasenclever, and Georg Kaiser, as well as paintings by Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Primarily associated with an individual character or author’s point of view, German Expressionism concerned distorted perspectives emerging in art, hence its significant influence on Surrealism, Cubism, and Constructivism—and many other subsequent movements that present reality through a filter of aesthetic and reality-distorting principles. The term would become so popular that expressionism became commonplace outside of the so-called movement, influencing a general quality used by artists to interpret reality through an emphatic lens that, in cinema’s case, saturates every aspect of the mise-en-scène.

Few films from the 1920s commit so fully to the qualities associated with German Expressionism, making Caligari a singular case to represent the phenomenon. But rather than dwell on the modernist principles of German Expressionism and how Caligari aligns with them, it’s more rewarding to appreciate the specific flourishes found in the film. The visuals remain one of its lasting points of fascination. The backdrops have been accented by literal brushstrokes, with bold, jagged lines, like a charcoal sketch or painting made by a passionate fine artist. These irregular borders, made with intentional but dramatic gestures in paint by Warm’s designers, seldom form patterns and only hint at their meaning, such as the allusions to sidewalks and windows. They do not amount to precise representations, but they also do not confound in the same manner that a scrawl or sloppy handwriting is still decipherable. These visual distortions reconfigure the world in a series of asymmetrical shapes and juxtapositional surfaces, working against naturalism to convey a decorative and emotive visual understanding of any given scene, beyond the narrative. The artistic impression of the world overall has a frightening and bizarre logic, so its pointed angles and scribbled borders present a consistent, if haunting, surface aesthetic.

These designs have an intended motion, evocative of emotion, and present a defiantly unreal space that is reflective of its storyteller’s mental state—warped because he is a murderer or has been convinced he is one. It’s important to note that German Expressionism in cinema, like much silent-era cinema, took its greatest influence from theater, specifically Expressionist theater, leading to Caligari’s stagelike set pieces and theatrical staging of each scene. This quality is less evident in the camerawork. Wiene and cinematographer Willy Hameister resist cockeyed angles or lenses, presenting most scenes in the tableau format often associated with early cinema. But the false-perspective sets and graphical designs suggest an unnatural world without the aid of distinct camerawork; the painterly nature of the sets, along with their sharp angles and high-contrast lighting—often realized with paint rather than actual lights, which illuminated sets from the conventional front and sides—achieve the intended impact. Rooms and structures avoid 90-degree angles and often seem to tilt and lean for an off-kilter effect. The actors, too, perform in grand gestures, partly because silent cinema actors usually came from the theater stage, where acting requires larger-than-life bravado to reach the rear theater, but also partly because the material demands it. The most pronounced demonstration arrives when Cesare, with Veidt’s face in close-up, awakens—his eyes slowly open, sleepy, but then jolt horrifyingly alive in an image for the ages.

When it opened in late February 1920, Caligari was received with fascination by critics and embraced by audiences. An elaborate marketing campaign created a buzz, with a tagline (“You must become Caligari!”) featured on the poster and newspaper ads to generate interest. Decla-Film also promoted Giuseppe Becce, a famous and prolific silent-era composer, whose music would accompany the initial run—although his score rarely plays with the picture today in repertory screenings or physical media and streaming releases. Caligari performed well for several weeks and continued to earn attention abroad in the years to come. The Goldwyn company acquired the rights to distribute Caligari stateside, where it was a hit. In France, where a postwar anti-German mentality thrived, Caligari was celebrated and ushered in a new acceptance of German cinema. It was recognized as an instant landmark and natural evolution of Expressionism from the so-called high forms of art, such as painting, literature, and theater, to the new and low form of popular and commercial artform of cinema. However, due to the sociopolitical volatility of this postwar period in Germany, followed by the rise of fascism and World War II in the subsequent decades, Caligari was not put in its appropriate historical context until Kracauer’s assessment.

Caligari helped usher a wave of German Expressionist films and commercial exports to other nations interested in seeing this strange new type of product. But its legacy extends further. The decades to follow saw Hollywood filmmakers such as James Whale (Frankenstein, 1931), Orson Welles (Citizen Kane, 1941), Carol Reed (The Third Man, 1949), and Charles Laughton (The Night of the Hunter, 1955) learning lessons from Wiene’s suggestion of angles and dramatic, graphical light. Film noir, with its shadows and stylized camera angles, its fatalism and moral ambiguity, was born out of German Expressionism—many European filmmakers who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s brought that style to Hollywood’s noir pictures. And what would Tim Burton’s early career be without Caligari? His embrace of its dramatic lines appears in Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure (1985), his conception of the bureaucratic afterlife informs Beetlejuice (1988), his visualization of the titular Edward Scissorhands (1990) is a nod to Cesare, and his expressive environment in Sleepy Hollow (1999) owes much to this silent classic. Even further, the entire horror genre has, consciously or not, drawn from Caligari’s influence. Its heightened use of shadows, angular designs, grim mood, and uncanny atmosphere has given way to Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965), Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977), Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook (2014), and countless other examples. There was even a psychosexual spiritual sequel, Dr. Caligari, released in 1989, that bridged Expressionist designs with hyper-horny experimental cinema and the angular ostentatiousness of ’80s pop culture.

Today, there’s a tendency among scholars, such as Jerome Ashmore, to associate Caligari with cinematic high art. Art is often placed into categories of high and low; cinema is no exception. In the broadest and somewhat stereotypical terms, high-art cinema targets the affluent and sophisticated; commercial or low cinema appeals to the masses. But with Caligari, as Robinson observes, “We have to recognise that it was made, knowingly and strategically, in the main line of the commercial production of its day, with the ‘art’ element calculated as an extra and positive, if speculative, box-office attraction.” Neither its producers nor its film-workers had the ambition to create an art piece; they sought to contribute something artistically novel to popular entertainment. The film’s status as high art in some estimations, then, remains justified from a certain point of view—specifically in that if art survives the test of time, regardless of its intended meaning or audience, it tends to be canonized among the Great Works. These qualifiers are not intended to downgrade Caligari; they only acknowledge its status over time.

If this is true, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari marks a rare occasion where a significant advancement in the artistic qualities of filmmaking is matched with a narrative that has widespread and lasting appeal, offering that rare sweet spot where the high and low meet. The film’s enduring quality, having celebrated its centenary in 2020, certainly contributes to its venerable place in the medium’s legacy. Its sheer staying power often negates the reality that the film, its style notwithstanding, was considered common at the time—the era’s equivalent to pulp fiction. This is, after all, a story with a climax that, had it appeared in a Hollywood thriller, would be criticized for deploying a prosaic cliché tantamount to “It was all a dream” or the generic split-personality device. Recent movies, such as Jacob’s Ladder (1990), Fight Club (1999), Identity (2003), Secret Window (2004), Shutter Island (2010), and numerous others, take place inside disturbed minds. The novelty of watching Caligari today is that one seldom links silent-era cinema with narrative games of this kind. The usual, straightforward silent thriller unfolds with reliable narrators guiding the viewer through a chronological scenario, with few shocking twists or turns to shake the audience’s assumptions about the film-world’s reality. Besides expanding the toolkit for countless other filmmakers, the film remains a tense and entertaining horror yarn, achieved with an uncommon expressive artistry. Whereas realism and naturalism are often celebrated for replicating reality, Caligari offers an alternative: a visually unnatural and distorted nightmare.

(Note: This essay was originally posted to Patreon on October 29, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Ashmore, Jerome. “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari as Fine Art.” College Art Journal, vol. 9, no. 4, 1950, pp. 412–18. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/773704. Accessed 21 September 2024.

Budd, Mike. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Texts, Contexts, Histories. Rutger University Press, 1990.

—. “Retrospective Narration in Film: Re-Reading ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.’” Film Criticism, vol. 4, no. 1, 1979, pp. 35–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44018648. Accessed 21 September 2024.

Cardullo, Bert. “Expressionism and the Real ‘Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.’” Film Criticism, vol. 6, no. 2, 1982, pp. 28–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44018696. Accessed 21 September 2024.

Donahue, Neil H. “Unjustly Framed: Politics and Art in ‘Das Cabinet Des Dr. Caligari.’” German Politics & Society, no. 32, 1994, pp. 76–88. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23736328. Accessed 21 September 2024.

Hubbert, Julie. “Modernism at the Movies: ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ and a Film Score Revisited.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 88, no. 1, 2005, pp. 63–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3601013. Accessed 21 September 2024.

Kracauer, Siegfried. From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film. Princeton University Press, 1947; 2004.

Pratt, David B. “‘Fit Food for Madhouse Inmates’: The Box Office Reception of the German Invasion of 1921.” Griffithiana 4/49, October 1993, pp. 95-157.

Robinson, David. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. BFI Film Classics. Bloomsbury, 2013.

Thompson, Kristin, et al. Film History: An Introduction, 5th Edition. McGraw Hill, 2022.

Thompson, Kristin. “Early Alternatives to the Hollywood Mode of Production: Implications for Europe’s Avant-Gardes.” Film History, vol. 5, no. 4, 1993, pp. 386–404. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27670732. Accessed 21 September 2024.

Walker, Julia A. “‘In the Grip of an Obsession’: Delsarte and the Quest for Self-Possession in ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.’” Theatre Journal, vol. 58, no. 4, 2006, pp. 617–31. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25069918. Accessed 1 October 2024.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review