The Definitives

Ikiru

Essay by Brian Eggert |

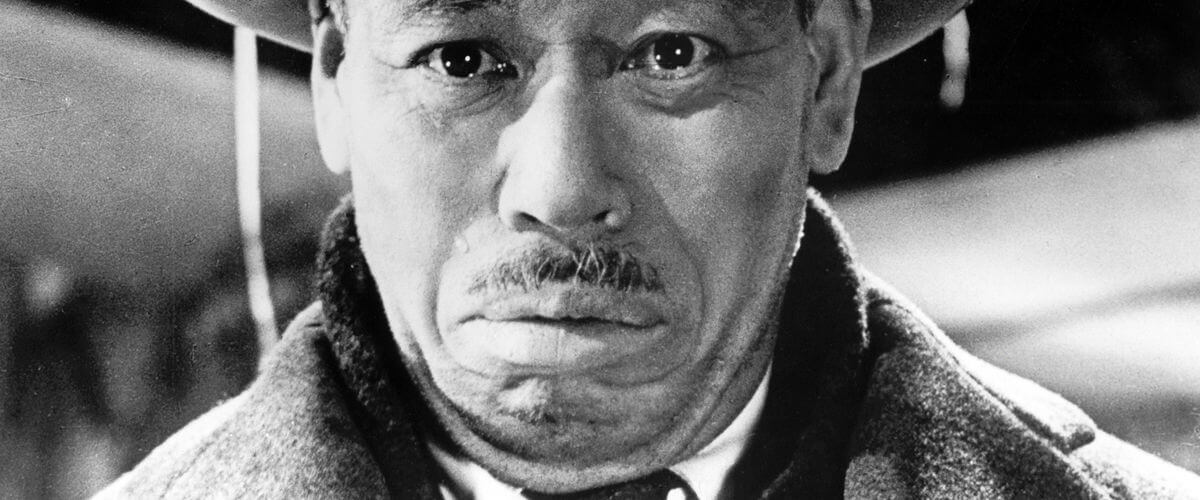

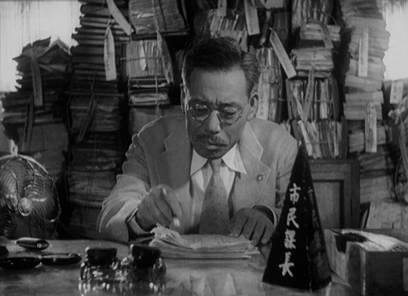

Kanji Watanabe toils as a paltry Section Chief at the Public Affairs division in City Hall, stamping forms and adding to towers of endless paperwork, wrapping himself in departmental red tape. Appropriately, his subordinates call him “The Mummy,” alluding to his coldly official disposition. Approached by a group of neighborhood women hoping to clean up and replace a local sump with a park, Watanabe sends them along through proper channels, knowing that ultimately they will be shuffled until they finally end up exactly where they began. Watanabe is a cog in the efficient clockwork of bureaucracy, his existence circling, meaningless until the moment he learns that he has only six months to live. Much of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru takes place in the time before Watanabe’s death, when the character, played by the great Takashi Shimura, discovers his own sense of affirmation. Diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer, Watanabe faces his mortality and the emptiness of his life as he lived it. He commits himself to a last passionate undertaking, vowing to transform his administrative position from one of hollow officialdom to one of proactive decision-making. Battling Japan’s postwar establishment, which he helped maintain for most of his life, Watanabe vows to organize various municipal bureaucracies to clean up the pool of impure, mosquito ridden, stagnant water and put up a park where children are safe to play. In doing so, he gives his life some meaning and finds his own definition for what it means to be alive.

The film was released in 1952, just after Kurosawa’s pivotal international success Rashomon and just before his iconic epic Seven Samurai. Despite the notoriety of his name in the global film circuit, Ikiru would not receive distribution in the United States until 1960, attributing to claims that it was “too Japanese.” Curious, since Kurosawa is often considered the most western of all Japanese filmmakers, making pseudo-Westerns like Yojimbo and Sanjuro set in feudal Japan and inspired by American director John Ford. However, Ikiru has neither the exotic samurai appeal nor the outright entertainment value of his other work, but it does speak in a universal language of humanism. Highly praised in Japan, the academic film journal Kinema Junpo named it the best picture of the year; when the film eventually reached other markets, because the message is not contingent on race or culture but on humanity, it was just as revered.Written by Shinobu Hashimoto and Kurosawa, with input on the structure from collaborator Hideo Oguni, the film’s story originated from Kurosawa’s loathing of the omnipresent corporate corruption in postwar Japan.

During the Allied occupation after WWII, large business trusts known as zaibatsu had begun to slowly regain control of Japan’s economy and apply their influence on the government, despite the Allied intent that former commercial powers would be removed from their places through the reconstruction. This helped raise a distinct separation of classes in Japan and furthered the country’s collective postwar malaise. Kurosawa’s resentment that the same pre-war bureaucrats remained in control in the postwar climate was evident; he addressed the same subject head-on in The Bad Sleep Well, and to a degree in High and Low, though all of his postwar films contain an undercurrent of this social commentary. It is this public plague that Kurosawa seeks to represent with Ikiru, best illustrated in the human indecency that sends the neighborhood women on a futile paper trail to have the “sewage pond” cleaned away. Just as with Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel, the director uses an idle cesspool to represent Japan’s torpid postwar humanism. Kurosawa sought to cultivate a bureaucrat through Kanji Watanabe, though he avoids making the audience understand the character’s side by showing us the perspective of the official; rather, he removes the bureaucrat’s social mask and reveals the human being underneath.

The film’s narrator makes a quick assessment of Watanabe, acknowledging that the character works endlessly without doing anything at all, that “He might as well be a corpse. In fact, this man has been dead for more than 20 years now.” The narrator, a rare feature in Kurosawa pictures, talks the audience through the film as a sort of benshi, a raconteur of Silent Era motion pictures in Japan. Kurosawa’s brother, Heigo, served as a benshi long before the war, helping to instill the director’s passion for movies at an early age. With the presence of this contemplative and judgmental narrator, Kurosawa classifies Ikiru as an investigation into a man’s life, both analytical and morally critical, and he asks that the audience consider with grave importance everything shown to them. In the first scene, Kurosawa connects Watanabe’s illness, his state of failing, with his very being: A doctor examines an X-ray that shows cancer, and that image fades into Watanabe sitting at his station in the Public Affairs office, as if one figure defined the other. Later, Watanabe waits in the doctor’s office to hear his result, and a fellow patient warns him that if the doctor prescribes specific dietary instructions, then everything will be fine; but if the prognosis is a “mild ulcer” and Watanabe can eat whatever he likes, then he has stomach cancer and maybe six months to live. When the shifty-eyed, cowardly physician begins to recount verbatim the patient’s warning, Watanabe knows his time is short. At home, he weeps in his bed, reflecting on his life for the first time—everything from his broken relationship with his son to his vacuous career. The camera pans to an award on his wall praising him for 25 years of punctual service at City Hall, now a reminder of his wasted life.

The film’s narrator makes a quick assessment of Watanabe, acknowledging that the character works endlessly without doing anything at all, that “He might as well be a corpse. In fact, this man has been dead for more than 20 years now.” The narrator, a rare feature in Kurosawa pictures, talks the audience through the film as a sort of benshi, a raconteur of Silent Era motion pictures in Japan. Kurosawa’s brother, Heigo, served as a benshi long before the war, helping to instill the director’s passion for movies at an early age. With the presence of this contemplative and judgmental narrator, Kurosawa classifies Ikiru as an investigation into a man’s life, both analytical and morally critical, and he asks that the audience consider with grave importance everything shown to them. In the first scene, Kurosawa connects Watanabe’s illness, his state of failing, with his very being: A doctor examines an X-ray that shows cancer, and that image fades into Watanabe sitting at his station in the Public Affairs office, as if one figure defined the other. Later, Watanabe waits in the doctor’s office to hear his result, and a fellow patient warns him that if the doctor prescribes specific dietary instructions, then everything will be fine; but if the prognosis is a “mild ulcer” and Watanabe can eat whatever he likes, then he has stomach cancer and maybe six months to live. When the shifty-eyed, cowardly physician begins to recount verbatim the patient’s warning, Watanabe knows his time is short. At home, he weeps in his bed, reflecting on his life for the first time—everything from his broken relationship with his son to his vacuous career. The camera pans to an award on his wall praising him for 25 years of punctual service at City Hall, now a reminder of his wasted life.

Wrought with despair, Watanabe resolves to lose himself in selfish spending; he ignores protests from his distant son and daughter-in-law, as both are too concerned about their inevitable inheritance to notice his illness. With ¥50,000 in his pocket and no idea how to use it, he downs expensive sake in a bar, despite its sting in his stomach. Of the mind that spending money will free him of his limited existence, Watanabe is approached by a writer who calls himself Mephistopheles; he learns of Watanabe’s short time and offers to show the dying man how to spend his money. “Greed is a virtue,” says Mephistopheles, who teaches Watanabe only excess and how to live in a drunken stupor. A montage of pachinko parlors, a striptease, drinking, and laughter ensues, after which Watanabe cannot help but feel vacant. For him, this is not living. The weight of his wasted life still heavy on his shoulders, he silences a hopping boogie dive when he begins to sing “Life is Brief” in a solemn voice:

Life is brief,

Fall in love, maidens,

Before the crimson bloom fades from your lips,

Before the tides of passion cool within you,

For those of you who know no tomorrow,

Life is brief,

Fall in love, maidens,

Before your raven tresses begin to fade,

Before the flames in your hearts flicker and die

For those to whom today will never return.

When Watanabe fails to show up at work for several days, his coworkers and family begin to worry. A young woman from his office, Toyo (Miki Odagiri), anxious to quit, appears outside his home to obtain his official stamp so she may tender her resignation. He admires her youthful verve to leave the monotonous job, and he befriends her, spoiling her with plentiful meals and gifts. Meanwhile, he seeks desperately to grasp her childlike quality, impossibly trying to recover some semblance of his formative years; if only he can live like her for one day, then he will have truly lived. But nothing about her life is special, besides her youth and remaining time that Watanabe envies so. Toyo eventually finds a new job in a factory assembling toys for children, and she becomes bored with their friendship. On their final outing together, she remarks that her new job makes her feel good, as though it allows her to play with every baby in Japan. With that, Watanabe realizes what he must do, and he decides to make one important contribution to the world in his last months. As he rises to embark on his new undertaking, from the backdrop he is encouraged by the singing of “Happy Birthday” for a girl’s party, but Kurosawa makes it clear that the song celebrates Watanabe’s new life.

When Watanabe fails to show up at work for several days, his coworkers and family begin to worry. A young woman from his office, Toyo (Miki Odagiri), anxious to quit, appears outside his home to obtain his official stamp so she may tender her resignation. He admires her youthful verve to leave the monotonous job, and he befriends her, spoiling her with plentiful meals and gifts. Meanwhile, he seeks desperately to grasp her childlike quality, impossibly trying to recover some semblance of his formative years; if only he can live like her for one day, then he will have truly lived. But nothing about her life is special, besides her youth and remaining time that Watanabe envies so. Toyo eventually finds a new job in a factory assembling toys for children, and she becomes bored with their friendship. On their final outing together, she remarks that her new job makes her feel good, as though it allows her to play with every baby in Japan. With that, Watanabe realizes what he must do, and he decides to make one important contribution to the world in his last months. As he rises to embark on his new undertaking, from the backdrop he is encouraged by the singing of “Happy Birthday” for a girl’s party, but Kurosawa makes it clear that the song celebrates Watanabe’s new life.

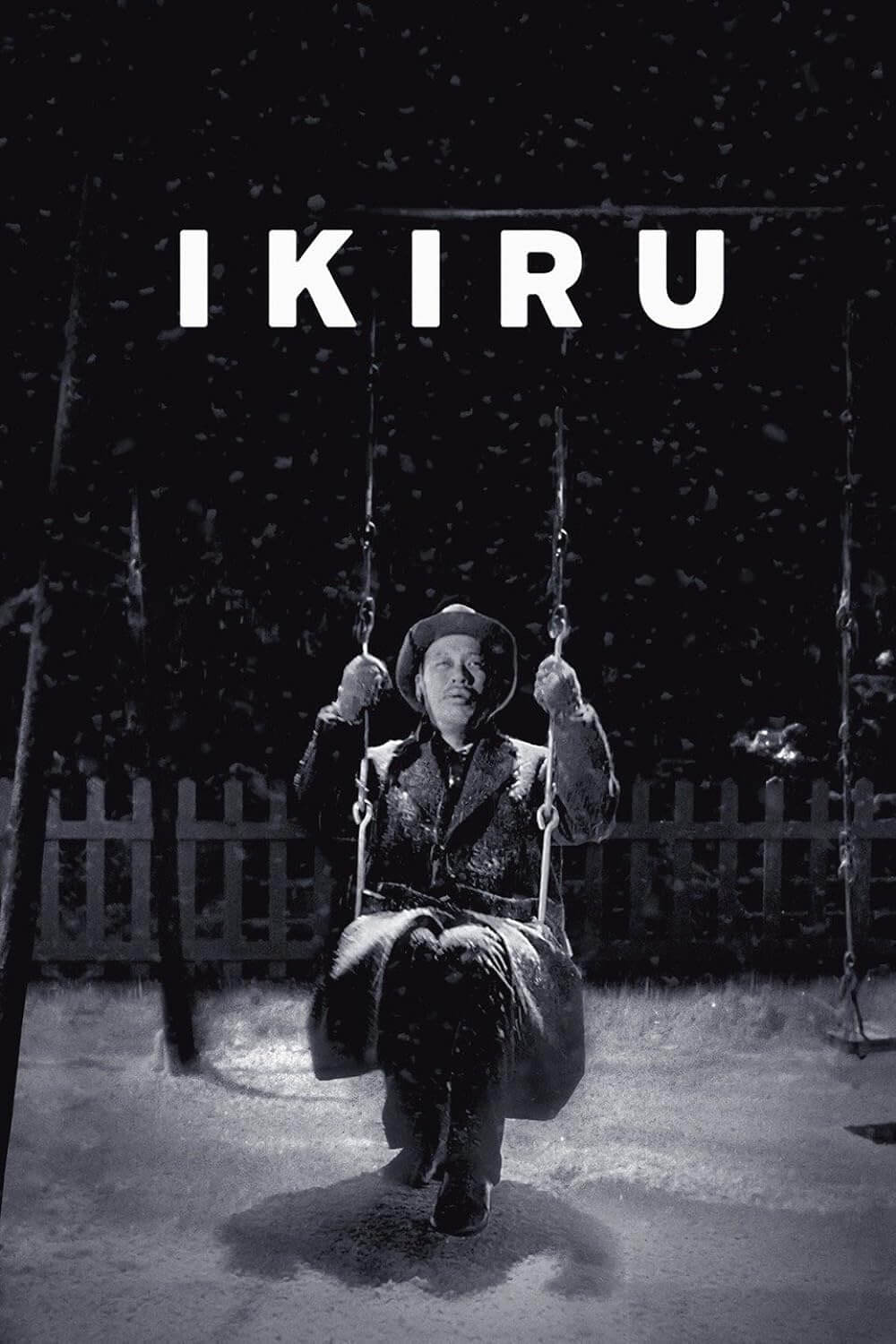

In Japanese, the word “ikiru” is a verb meaning “to live,” but Kurosawa’s title does not mean simply to exist. Neither partying nor the concept of youth meets its intended explication. For Kurosawa, the word implies that to truly live means a person must embrace life in all its grandeur; hence, those not embracing life are not truly alive. Watanabe, in his station at City Hall, died spiritually long ago. He stamped his forms, gave up his dreams, and bent in every which way to accommodate his position as Section Chief, existing not as a human being but as a subject to his employer. After his existential rebirth, Watanabe dedicates the last months of his life to helping the neighborhood women replace the putrid sump with a park for children; he files the correct paperwork, manipulates the neverending bureaucracy, and battles administrative idleness all in the name of this noble cause. In one cinema’s most touching, lyrical moments, upon his final triumph Watanabe sits on a swing in the park he helped build, snow falling lightly around him, and quietly sings “Life is Brief” in victory.

Kurosawa does not show Watanabe toiling to build the park, at least not from the compassionate perspective of the film’s first half. After the chapter with Toyo, the film shifts dramatically to five months later. Watanabe has died. His accomplishments are revealed through the memories of mourners at his wake. Family and coworkers devalue his late-life good deeds as the wake scenes unfold through an excess of drinking and talking. A debate ensues about Watanabe and if he knew that he had cancer; he never told his son, and whether or not he knew seems to enlighten the notion that building the park was an act of heroism. As a result, for the first-time viewer, Ikiru suddenly feels split down the center, as if two films were made about the same man, one from Watanabe’s standpoint, and the other looking in from a third party perspective. The narrative’s structural design—the mid-film shift to after Watanabe’s death—originated with Hideo Oguni, who had been a screenwriter for years but had never worked with Kurosawa. At that time, Oguni’s prior screenplays made humdrum films, but his narratives boasted a compositional sophistication that Kurosawa recognized, so he functioned as a vital story consultant on Ikiru. And though Oguni forced Kurosawa to scrap what pages of the script the director and Hashimoto had already completed, resulting in a temporary conflict between the elder writer and slightly younger director, Kurosawa learned to trust Oguni’s instincts. Their partnership would last some thirty years, through the making of Ran in 1985.

Kurosawa does not show Watanabe toiling to build the park, at least not from the compassionate perspective of the film’s first half. After the chapter with Toyo, the film shifts dramatically to five months later. Watanabe has died. His accomplishments are revealed through the memories of mourners at his wake. Family and coworkers devalue his late-life good deeds as the wake scenes unfold through an excess of drinking and talking. A debate ensues about Watanabe and if he knew that he had cancer; he never told his son, and whether or not he knew seems to enlighten the notion that building the park was an act of heroism. As a result, for the first-time viewer, Ikiru suddenly feels split down the center, as if two films were made about the same man, one from Watanabe’s standpoint, and the other looking in from a third party perspective. The narrative’s structural design—the mid-film shift to after Watanabe’s death—originated with Hideo Oguni, who had been a screenwriter for years but had never worked with Kurosawa. At that time, Oguni’s prior screenplays made humdrum films, but his narratives boasted a compositional sophistication that Kurosawa recognized, so he functioned as a vital story consultant on Ikiru. And though Oguni forced Kurosawa to scrap what pages of the script the director and Hashimoto had already completed, resulting in a temporary conflict between the elder writer and slightly younger director, Kurosawa learned to trust Oguni’s instincts. Their partnership would last some thirty years, through the making of Ran in 1985.

The diptych form of narrative was familiar territory for Kurosawa; he had explored such an outline in 1948 with Drunken Angel, and he would reuse the form again with High and Low in 1963. In the former, there were two stories to tell in the relationship between his doctor character (Shimura) and his gangster-patient character (Toshiro Mifune). In the latter film, Kurosawa examined a crime in the first half, and then the methodology used to track the criminal in the second. With Ikiru, Kurosawa studies a life as it changes from wholly empty to filled with intention, and then he considers how that life was viewed by others. The posthumous portion reveals itself to be tragically ironic, as the attendees at Watanabe’s wake talk of his life and grossly reduce it through their skewed perception of his final days. In each case with his diptych films, Kurosawa considers the relationship between the real and the ideal.

At the wake, the “electioneering” Deputy Mayor waves off the idea that one man could assemble so many of the departments needed to complete a public park. However, a few coworkers close to Watanabe know that though he did not personally drain the water or lay the gravel, without his passion for the project, the park would still be a written proposal circling in the bureaucratic turnstile of City Hall. They confess as much only after the Deputy Mayor leaves for the evening. Some at the wake hint that the park’s construction and Watanabe’s cancer are unconnected, blaming sentimentality for claims that the park was his life’s final mission. Drunken and moved by the conversation, one of the wake attendees comments, “But any one of us could drop dead.” The suggestion would then be that Watanabe’s coworkers should walk away enlightened, ready to use their status as public officials to help others. Of course, the next day at the office, Watanabe’s replacement in the role of Section Chief has learned nothing; he sends away a complaint to another department, handing off the responsibility and continuing the cycle of bureaucracy.

At the wake, the “electioneering” Deputy Mayor waves off the idea that one man could assemble so many of the departments needed to complete a public park. However, a few coworkers close to Watanabe know that though he did not personally drain the water or lay the gravel, without his passion for the project, the park would still be a written proposal circling in the bureaucratic turnstile of City Hall. They confess as much only after the Deputy Mayor leaves for the evening. Some at the wake hint that the park’s construction and Watanabe’s cancer are unconnected, blaming sentimentality for claims that the park was his life’s final mission. Drunken and moved by the conversation, one of the wake attendees comments, “But any one of us could drop dead.” The suggestion would then be that Watanabe’s coworkers should walk away enlightened, ready to use their status as public officials to help others. Of course, the next day at the office, Watanabe’s replacement in the role of Section Chief has learned nothing; he sends away a complaint to another department, handing off the responsibility and continuing the cycle of bureaucracy.

But how does the audience know if Watanabe’s story is real or sentimentalized? Perhaps his coworker-naysayers are accurate in their assessment of him; perhaps the momentous way in which Watanabe builds the park is the illusion. Certainly his triumphal turnaround from petty clerk to the affirmed savior of neighborhood sump has a melodramatic quality, a remarkable impossibility best reserved for dramatization. Kurosawa prevents his audience from falling into the same disbelieving trap as the wake attendees by solidifying the audience’s sympathy for Watanabe in the first half of the film, and by the coworkers remembering fragments that compile to a hopeful suggestion that one person can accomplish much if properly motivated. A sole coworker stands up against the others at the wake to defend Watanabe; Kurosawa leaves it ambiguous as to whether this clerk remembers correctly, or if perhaps in mourning the clerk has romanticized Watanabe’s life. What remains clear is that Watanabe’s life has had an effect on someone else, be it through the reality of his good deeds or through the mere perception of them. In the film’s last scene, the clerk walks home after seeing that his coworkers have learned nothing from Watanabe’s lesson; he stops on a bridge to regard Watanabe’s park, inspired by the lasting display of a meaningful life.

Ikiru’s purpose resides in perspective. Watanabe defines his life by taking action, through doing. Only by cleaning up the cesspool and building his park could Watanabe discover that, for him, to live means to do. As the confused and ultimately insignificant interpretations at the wake imply, it matters not what others think—the process of life-affirmation is a subjective one. The meaning of life is not defined via the opinions of coworkers and peers, not through what others think, but through how an individual assesses their own life in The End. As Kurosawa illustrates in the second half of Ikiru, outsiders cannot see the entire picture, so their judgments are incomplete and therefore meaningless. There is nothing more than an individual responsible for their own actions, bound only by their personal measurement of how fully their life was lived. A heartbreaking masterpiece that will inspire self-reflection, even a severe alteration of lifestyle in every viewer, the beautiful Ikiru is among the greatest, most life-affirming motion pictures ever made. How impossible to absorb Kurosawa’s message and not feel different somehow afterward. How impossible not to be moved, for a change not to be forced. Idleness will develop into action after viewing; contentment will become introspection. Cinema rarely reaches such profound emotional and existential heights. Kurosawa believes that the potential for human change exists, however infrequent; the sad truth of the film remains that only in the presence of death do most people reflect on life, whereas the film proposes that lives would be better lived if everyone knew how brief their time really was.

Ikiru’s purpose resides in perspective. Watanabe defines his life by taking action, through doing. Only by cleaning up the cesspool and building his park could Watanabe discover that, for him, to live means to do. As the confused and ultimately insignificant interpretations at the wake imply, it matters not what others think—the process of life-affirmation is a subjective one. The meaning of life is not defined via the opinions of coworkers and peers, not through what others think, but through how an individual assesses their own life in The End. As Kurosawa illustrates in the second half of Ikiru, outsiders cannot see the entire picture, so their judgments are incomplete and therefore meaningless. There is nothing more than an individual responsible for their own actions, bound only by their personal measurement of how fully their life was lived. A heartbreaking masterpiece that will inspire self-reflection, even a severe alteration of lifestyle in every viewer, the beautiful Ikiru is among the greatest, most life-affirming motion pictures ever made. How impossible to absorb Kurosawa’s message and not feel different somehow afterward. How impossible not to be moved, for a change not to be forced. Idleness will develop into action after viewing; contentment will become introspection. Cinema rarely reaches such profound emotional and existential heights. Kurosawa believes that the potential for human change exists, however infrequent; the sad truth of the film remains that only in the presence of death do most people reflect on life, whereas the film proposes that lives would be better lived if everyone knew how brief their time really was.

Bibliography:

Galbraith IV, Stuart. The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. New York: Faber and Faber, 2002.

Goodwin, James. Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, c1994.

Kurosawa, Akira. Something Like An Autobiography. New York : Knopf: distributed by Random House, 1982.

Richie, Donald. The Films of Akira Kurosawa, Third Edition, Expanded and Updated. With additional material by Joan Mellen. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1996.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International: Distributed in the U.S. by Kodansha America, 2005.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review