The Definitives

Eyes Without a Face

Essay by Brian Eggert |

With Eyes Without a Face, Georges Franju gets under the skin. Everything about the film has been designed to unnerve and penetrate: its austere aestheticism, visual poetry, entrancing score, arcane performances, and imagery replete with symbolic potential. Not interested in repulsion or simple shocks, the French director makes the most of his pulpy scenario, creating vivid and unforgettable sights that sear themselves into the unconscious. If the film does not reach deep into the viewer’s heart or establish characters who demand an audience’s affection, its narrative and thematic designs, in all their unromantic severity, prove unshakable. Franju’s assault on mannered cinematic sensibilities caused an uproar in 1960, earning the film decades of dismissal before its eventual reassessment as a work of horror-art. Today, Eyes Without a Face embodies a rather disquieting brand of deviation that aligns with Franju’s worldview in iconic ways. The film raises a marginalized genre to the status of art; it implants suspicion about established institutions; it considers the corruption of Nature in the name of advancement; and it portrays innate fears about the loss of identity, both physical and psychological, and their dehumanizing effect.

When a French journalist interviewing Franju for television described Eyes Without a Face as a “horror film,” the director corrected him. “It wasn’t a horror film. It was a terror film, which is worse.” The remark speaks to the stigmatized status of horror in France in the 1950s and 1960s. Among French critics, horror was situated under the umbrella category of the fantastique—a broad genre used predominantly by French and some other European literary scholars. French critics relied on descriptors developed out of older continental European literary traditions dating back to the Middle Ages, including the stuff of mythology, folklore, fairy tales, Arthurian legend, Gothic novels, and fantasy. By contrast, Hollywood determined film genres according to industry trends, often crafting, developing, and specifying genres according to what sold at the box office. So, American and British critics distinguished horror and science fiction as separate genres. On the whole, the French considered cinéma fantastique a minor and unimportant genre in film, dismissing its entries almost as a rule to instead support standards of good taste and the so-called Tradition of Quality sought by the country’s mainstream film industry.

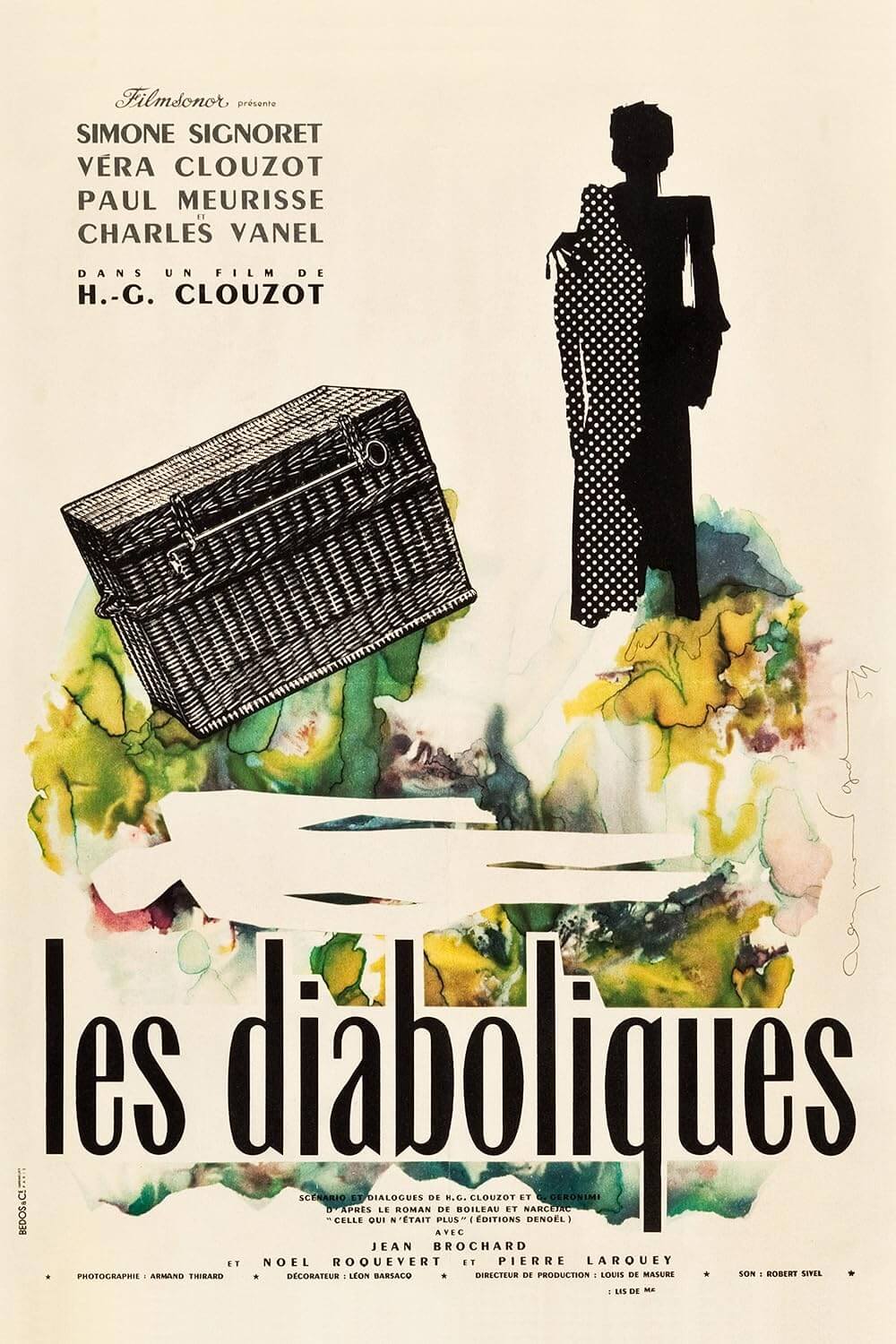

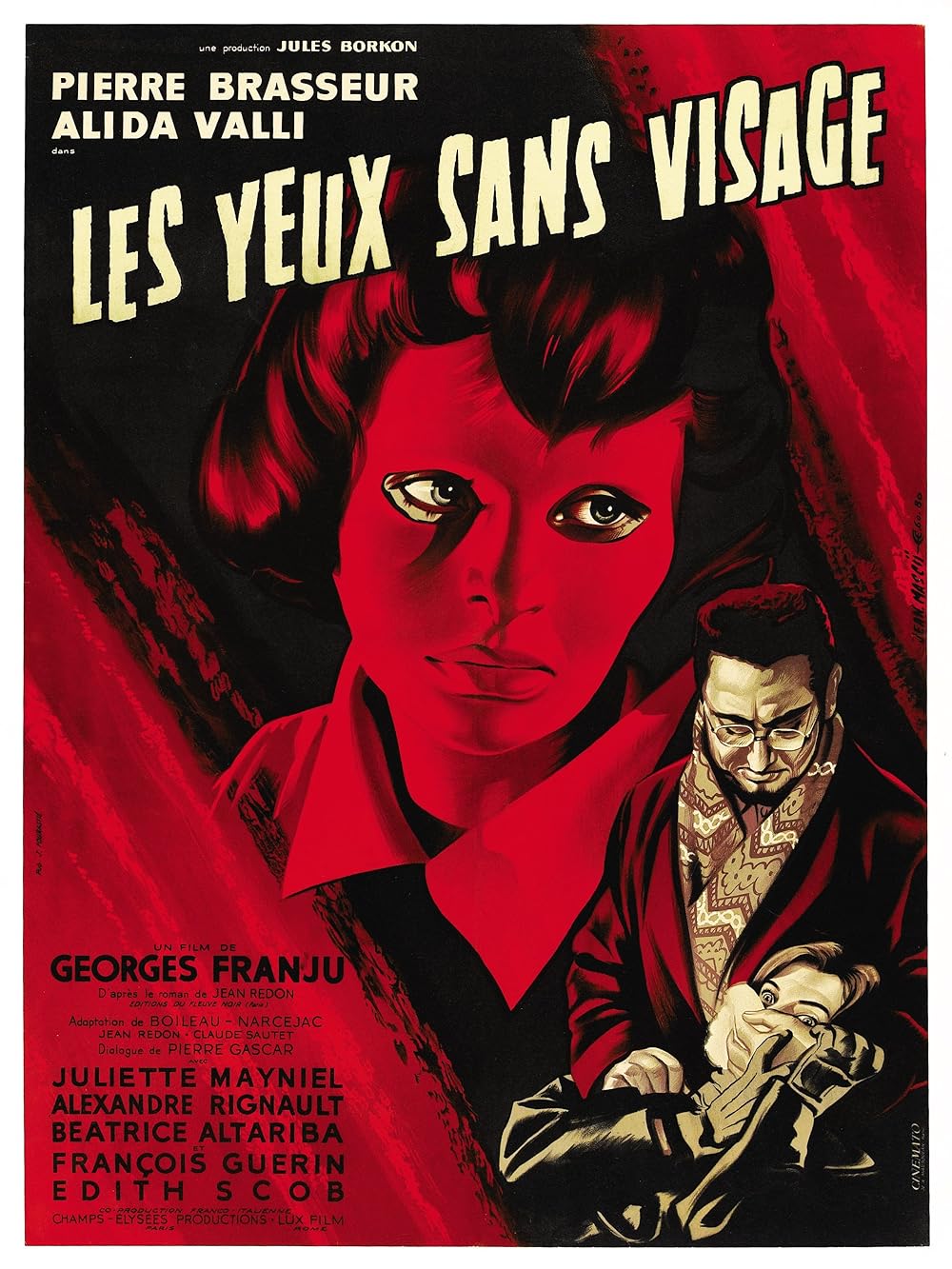

But producer Jules Borkon saw horror as a financial opportunity, so he bought the rights to the 1959 novel Les Yeux sans visage by Jean Redon. The original text contained many characteristics of a traditional horror film: a mad doctor who bends science to create an abomination, recalling Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; an old dark house, complete with a dungeon and laboratory; and a series of female victims. Not only that, but the story featured elements of a policier—a portion of the plot follows a police investigation. Borkon recognized similarities between Redon’s book and the moneymaking productions by the British studio Hammer Films, which had forever changed horror cinema in the 1950s. Director Terence Fisher reimagined classic monsters with Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Horror of Dracula (1958), and their many sequels, shooting in full color and dousing them in gore. Hammer’s example had resulted in moneymakers in the UK and US, but no French filmmakers had tried anything so visceral. Sure, Henri-George Clouzot explored bloodless suspense with The Wages of Fear (1953) and Diabolique (1955), earning him many comparisons to Alfred Hitchcock. But suspense and horror belonged in separate categories according to French critics at the time, and they considered the latter a lesser artistic enterprise.

But producer Jules Borkon saw horror as a financial opportunity, so he bought the rights to the 1959 novel Les Yeux sans visage by Jean Redon. The original text contained many characteristics of a traditional horror film: a mad doctor who bends science to create an abomination, recalling Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; an old dark house, complete with a dungeon and laboratory; and a series of female victims. Not only that, but the story featured elements of a policier—a portion of the plot follows a police investigation. Borkon recognized similarities between Redon’s book and the moneymaking productions by the British studio Hammer Films, which had forever changed horror cinema in the 1950s. Director Terence Fisher reimagined classic monsters with Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Horror of Dracula (1958), and their many sequels, shooting in full color and dousing them in gore. Hammer’s example had resulted in moneymakers in the UK and US, but no French filmmakers had tried anything so visceral. Sure, Henri-George Clouzot explored bloodless suspense with The Wages of Fear (1953) and Diabolique (1955), earning him many comparisons to Alfred Hitchcock. But suspense and horror belonged in separate categories according to French critics at the time, and they considered the latter a lesser artistic enterprise.

Borkon gave the project to Franju, who had just completed work on his debut feature, Head Against the Wall (1959), about a man wrongly committed to an insane asylum. Franju was no stranger to provocative imagery, either; he seemed compelled to tell stories about what happens behind closed doors. His 22-minute short, Blood of the Beasts (1949), juxtaposes footage of children playing and lovers embracing against gut-wrenching footage of cows and horses processed in a slaughterhouse—with imagery unflinching enough to put the most ravenous carnivore off meat. He also made Hôtel des Invalides in 1952, a short about a Paris veterans hospital turned museum, revealing the hidden truth of war. Franju also took the artistic merits of cinema more seriously than most, having teamed with Henri Langlois, Jean Mitry, and Paul Auguste Harlé to launch the Cinémathèque française in 1936, which remains the most significant film preservation and historical organization in France. However, unlike so many of his contemporaries, he did not adhere to the so-called Tradition of Quality that dominated the establishment of French cinema, nor did he subscribe to the philosophies that drove the emerging New Wave. Inspired by the silent-era’s Louis Feuillade and George Méliès—filmmakers who embraced cinéma fantastique and made him fall in love with its limitless potential—Franju gravitated toward genre and deviancy. He adored pulpy stories and, in the following years, would go on to explore them in Spotlight on a Murderer (1962) and Judex (1963), the former an Agatha Christie-style whodunit and the latter based on a Saturday matinee serial.

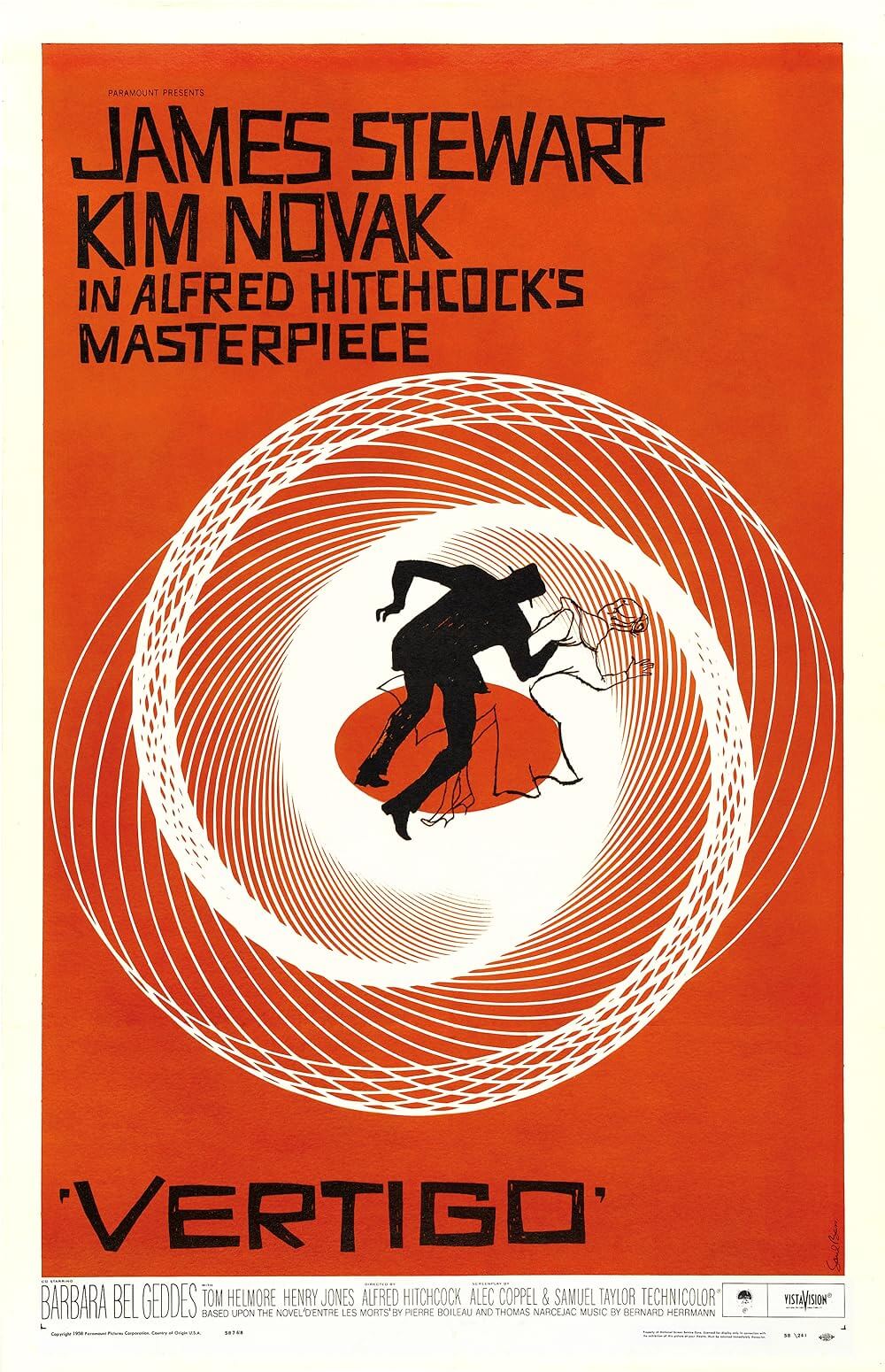

Working on Eyes Without a Face, Franju hoped to elevate the minor genre and reveal its possibilities by combining a pulpy narrative with haunting, expertly crafted, and dreamlike visuals. But first, he had to drastically change the story in Redon’s novel. The text follows Dr. Génessier, a surgeon who hopes to give his daughter Christiane, whose face was horribly disfigured in a car accident with him at the wheel, a new face, and so he kills young women for material to complete the procedure. “The mad doctor was a drunk and his assistant was a madman who was on drugs and raped the corpses,” Franju described, detailing the original scenario for writer Randall Conrad. “The doctor got arrested at the end and his daughter committed suicide at the sight of her father in handcuffs. It was too dumb for words.” So Franju conceived of a new ending and replaced the necrophiliac with Génessier’s loyal henchwoman named Louise. He also enlisted Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, authors of the source material for Diabolique and Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), to write the screenplay. The writers, whose names were synonymous with psychological suspense, reworked the book’s perspective, shifting the focus away from the mad scientist and toward Christiane, the masked daughter.

In developing the project, Franju walked a narrow path between good taste and bad, between reality and the fantastical, between his own artistic impulses and the requirements of his producer. While Borkon felt the material bore enough similarities to classic Hollywood horror films to sell in the US—James Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) above all others—he needed a film that would be marketable to UK audiences accustomed to bloody Hammer productions, and he would have to avoid associations with the unthinkable experimentations by Nazi doctors to appease the German market. The director cast his picture according to marketability as well. To play Génessier, Franju cast Pierre Brasseur, an established French actor who performed in the country’s most celebrated epic, Les Enfants du Paradis (1945). For the rest of the cast, Franju explained to Conrad, “We got Italy by having Alida Valli, and Germany by having Juliette Mayniel [as a victim] because a film she made with Chabrol had just done well there. Yet the star was an unknown, Edith Scob—because that’s how I wanted it.” Franju cast Scob, who had appeared in Head Against The Wall and would work with him again many times, as Christiane because he wanted the character’s face to remain a mystery behind her mask. Franju planned to make the mask an iconic image that would go beyond dialogue, beyond character, and burn itself into the audience’s retinas.

In developing the project, Franju walked a narrow path between good taste and bad, between reality and the fantastical, between his own artistic impulses and the requirements of his producer. While Borkon felt the material bore enough similarities to classic Hollywood horror films to sell in the US—James Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) above all others—he needed a film that would be marketable to UK audiences accustomed to bloody Hammer productions, and he would have to avoid associations with the unthinkable experimentations by Nazi doctors to appease the German market. The director cast his picture according to marketability as well. To play Génessier, Franju cast Pierre Brasseur, an established French actor who performed in the country’s most celebrated epic, Les Enfants du Paradis (1945). For the rest of the cast, Franju explained to Conrad, “We got Italy by having Alida Valli, and Germany by having Juliette Mayniel [as a victim] because a film she made with Chabrol had just done well there. Yet the star was an unknown, Edith Scob—because that’s how I wanted it.” Franju cast Scob, who had appeared in Head Against The Wall and would work with him again many times, as Christiane because he wanted the character’s face to remain a mystery behind her mask. Franju planned to make the mask an iconic image that would go beyond dialogue, beyond character, and burn itself into the audience’s retinas.

Chillingly, the film opens with the disposal of a corpse. Louise (Valli) drives at night in a similar shot and paranoid state as those of Marion Crane in Hitchcock’s Psycho, which would reach theaters just a few months after Eyes Without a Face. Stopping on a country road near a river, Louise hauls out the body of a naked woman wrapped in a man’s coat, her bare legs and feet dangling, and plunges the evidence down into the water. The next time Franju shows Louise, she appears next to Génessier, a famous surgeon who lectures on his new “heterograph” technique that could revolutionize skin transplants. Brasseur plays Génessier under a convincing bulk as evidence of his privilege and egoism, but he’s also driven by a sense of personal responsibility, warped by his scientific mindset. At his secluded villa, near his clinic in the Paris suburbs, he resolves to carry out wicked acts to restore his daughter. Her face, now covered by a mask of his own design, serves as a reminder of his failure, compelling him to correct it by any means. “I’ve done so much wrong to perform this miracle,” he reflects. And while Génessier’s cause proves sympathetic enough to avoid turning him into a cartoonish monster (What father wouldn’t want to repair his daughter’s face?), his methods and personal limits have twisted and extended over time. What begins as experimentation on stray dogs spirals into the abduction and murder of women, dubbed “donors” or, as critic Brian Glasser put it, “human sacrifices on the twin altars of his medical hubris and sense of guilt.”

In his 2013 essay about the film for The Criterion Collection, Patrick McGrath claims, “What we have is a lunatic father impelled to perform ever more desperate acts of violence to make his child good once more.” But “lunatic” feels like a strong word in this case. Génessier may seem outwardly detached and methodical, but he’s not the serial killer who takes pleasure in his work. He’s not even Colin Clive’s doctor in Frankenstein (1931), who, in a moment of creation declares with a hint of madness, “Now I know what it feels like to be God!” Rather, if Christiane’s face could easily be restored by the same magic performed in, say, John Woo’s Face/Off (1997), Génessier would no doubt stop his crimes and return to his normal duties. His moral corruption has developed gradually with the cold logic of science, through increased experimentation and desperation, to the point where he hardly recognizes his moral leap. And yet, for all Génessier’s personal motivations, he is not oblivious to the professional applications and personal benefits either. “If this were a success,” he reflects, “God! You couldn’t put a price on it.” He even mentions the potential for eternal youth in an early lecture scene, suggesting Génessier has thought about other applications for his experiments. His plan, which entails Louise scouting and capturing young women who resemble Christiane, feels compelled by the same sinister motivations that drove nineteenth-century doctors to pay for corpses for anatomy lectures and experimental dissections—even if it meant committing murder.

Eyes Without a Face also follows the French literary tradition of facial masking and disfigurement established in Alexandre Dumas’ Man in the Iron Mask, Victor Hugo’s The Laughing Man, and Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera. The face is not only the physical form of the person who wears it in these authors’ works but the site of recognition, expression, and identity. In each case, the protagonist’s face is mutilated or masked, robbing them of their selfhood. So, too, is Christiane robbed of her identity by literal defacement. Her father’s plan will not give Christiane back her face but rather the face of another; even if the procedure proves successful, she will not be restored to her former self. She will be left with no identity, though her father insists she can craft a new one. “Won’t that be fun?” Still, when she wanders into her father’s laboratory and removes her mask to look into the mirror, apparently for the first time, she does not recognize the disfigured person she sees. Then she moves to regard Louise’s recent catch, Edna (Mayniel), and admires what will become her new face. Tied down to a gurney, Edna stirs, but Christiane does not move away or cover her face. The camera shifts to Edna’s point of view, where Christiane appears distorted. Whether Christiane has receded into the darkness or Edna’s eyesight remains fuzzy from drugs given to her, the image is obscured. She has become symbolically inhuman, transformed by her facelessness into a looming figure willing, at that moment anyway, to take part in her father’s plan. Edna can do nothing more than scream—a blood-curdling reaction only outdone by Mia Farrow’s response to her infant’s appearance in Rosemary’s Baby eight years later.

Eyes Without a Face also follows the French literary tradition of facial masking and disfigurement established in Alexandre Dumas’ Man in the Iron Mask, Victor Hugo’s The Laughing Man, and Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera. The face is not only the physical form of the person who wears it in these authors’ works but the site of recognition, expression, and identity. In each case, the protagonist’s face is mutilated or masked, robbing them of their selfhood. So, too, is Christiane robbed of her identity by literal defacement. Her father’s plan will not give Christiane back her face but rather the face of another; even if the procedure proves successful, she will not be restored to her former self. She will be left with no identity, though her father insists she can craft a new one. “Won’t that be fun?” Still, when she wanders into her father’s laboratory and removes her mask to look into the mirror, apparently for the first time, she does not recognize the disfigured person she sees. Then she moves to regard Louise’s recent catch, Edna (Mayniel), and admires what will become her new face. Tied down to a gurney, Edna stirs, but Christiane does not move away or cover her face. The camera shifts to Edna’s point of view, where Christiane appears distorted. Whether Christiane has receded into the darkness or Edna’s eyesight remains fuzzy from drugs given to her, the image is obscured. She has become symbolically inhuman, transformed by her facelessness into a looming figure willing, at that moment anyway, to take part in her father’s plan. Edna can do nothing more than scream—a blood-curdling reaction only outdone by Mia Farrow’s response to her infant’s appearance in Rosemary’s Baby eight years later.

However insidious Génessier’s scheme may seem, there’s a twisted measure of practicality behind it, capturing Franju’s rare talent for blending the fantastique with plausible science, the outlandish with the commonplace. The same dynamic accompanies the director’s Blood of the Beasts, where he frames unthinkable violence on living creatures as the method by which people receive their regular helpings of protein. In Eyes Without a Face, Franju treats Génessier’s procedure with clinical objectivity, as though watching an anatomy lesson. The six-minute sequence performed on Edna shows Génessier marking a line around her face and eyes, then slowly pulling a scalpel across that line, stopping only so Louise can wipe his sweaty brow. He loosens the skin from her face and, with Louise’s help, gently pulls the flesh away in a single piece. After the procedure, Edna, too, becomes a faceless nonentity. When she wakes and realizes this, she rushes upstairs to escape and either falls or throws herself out of a window—prompting Génessier and Louise to hide her corpse in the family tomb, which already contains their first kidnapping victim, buried under Christiane’s name. As for Christiane’s new face, it looks almost ethereal. Louise remarks that it has “something angelic that wasn’t there before.” Something “from Beyond,” Christiane adds. But the new face lasts only a short while before her body rejects the new skin. Franju shows the decay in a series of medical photographs that document the deterioration in grotesque detail.

Following another failed procedure, Christiane becomes despondent. “Let me be dead for good,” she cries. Desperate to save his hopeless daughter, Génessier and Louise attempt to fastrack another victim, another surgery. But the police set a trap with the help of Christiane’s former fiancé Jacques (François Guérin), using a young woman, Paulette (Béatrice Altariba), as bait. However, it’s too late for Christiane; the latest failure has ensured her submersion into facelessness. In the climax, Christiane resolves to release Paulette from the operating table. In the chaos that follows, Christiane stabs Louise in the neck with a scalpel, then releases the dozen or so dogs that Génessier has kept for his experiments. Génessier arrives on the scene just in time to confront his pack of test subjects, who maul him, leaving him dead, his face ironically torn to shreds. Christiane has done this not because of a moral epiphany; instead, she has become exhausted by the endless process and protracted absence of identity. She resolves to stop the cycle of hope and disappointment by altogether removing the possibility of hope. In doing so, she frolics into the forest among birds she has released from her father’s cage, becoming a ghostlike apparition in the famous final shot.

Eyes Without a Face came out at a time before realistic gore was commonplace in the horror genre. Although schlocky B-movies and Hammer productions featured blood, none went so far as to present viscera in a realistic manner. Audiences weren’t ready for it, as the first screenings proved. Well before Franju’s film debuted in Paris on March 2, 1960, a sneak peek held for a Paris film club resulted in several spectators fainting during the surgery scene. Similarly, when it was screened at the Edinburgh Film Festival, seven viewers reportedly passed out and had to be carried out of the theater. Franju mocked them: “Now I know why Scotsmen wear skirts.” Given the reactions, critics responded as though Franju had betrayed every boundary of good taste. French critics dismissed the film, using words like “puerile” not because they believed the film bad, but because the genre was deemed unworthy. At odds with his reaction, Cahiers du cinéma critic Michel Delahaye refused to categorize the film as horror, arguing for its relationship to film noir. Outside of France, critics unleashed their outrage. The London Observer described the film’s “ghastly elegance that recalls Tennessee Williams in one of his more abnormal moods.” Dilys Powell’s review for the British newspaper the Sunday Times called it “deliberately revolting,” as though horror films should aspire to make audiences feel comfortable in their skin.

Eyes Without a Face came out at a time before realistic gore was commonplace in the horror genre. Although schlocky B-movies and Hammer productions featured blood, none went so far as to present viscera in a realistic manner. Audiences weren’t ready for it, as the first screenings proved. Well before Franju’s film debuted in Paris on March 2, 1960, a sneak peek held for a Paris film club resulted in several spectators fainting during the surgery scene. Similarly, when it was screened at the Edinburgh Film Festival, seven viewers reportedly passed out and had to be carried out of the theater. Franju mocked them: “Now I know why Scotsmen wear skirts.” Given the reactions, critics responded as though Franju had betrayed every boundary of good taste. French critics dismissed the film, using words like “puerile” not because they believed the film bad, but because the genre was deemed unworthy. At odds with his reaction, Cahiers du cinéma critic Michel Delahaye refused to categorize the film as horror, arguing for its relationship to film noir. Outside of France, critics unleashed their outrage. The London Observer described the film’s “ghastly elegance that recalls Tennessee Williams in one of his more abnormal moods.” Dilys Powell’s review for the British newspaper the Sunday Times called it “deliberately revolting,” as though horror films should aspire to make audiences feel comfortable in their skin.

Few European critics engaged with the film’s horror, and the response wasn’t much better in the US. After the distributor renamed it The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus and placed it on a double bill with a two-headed-beast yarn called The Manster (1959), Franju’s film didn’t have a chance —especially after US censors edited out the pivotal face-removal scene and any hint of sympathy for Génessier. Among the few to recognize something special in Franju’s treatment was Pauline Kael, whose review in The New Yorker proclaims, “It’s perhaps the most austerely elegant horror film ever made,” and praised its “vague, floating, lyric sense of dread which goes beyond the simpler effects of horror movies that don’t make intellectual claims.” She went on to write, “even though I thought its intellectual pretensions silly, I couldn’t shake off the exquisite, dread images.” Although mostly unappreciated in its time, Eyes Without a Face earned traction at midnight madness screenings and on late-night horror-host television. And who can say how much the film’s eventual reappraisal owes Billy Idol’s 1983 hit, “Eyes Without a Face,” a song that uses the French title “Les yeux sans visage” in the chorus? Widespread critical reassessment reached France in 1986 when the Cinémathèque française held a Franju retrospective as part of its fiftieth-anniversary celebration. In recent decades, Franju’s film has been heralded as a masterpiece, inspiring books such as Thierry Jonquet’s Tarantula (1984) and films including Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In (2011).

What cements Eyes Without a Face into the viewer’s mind is Franju’s interest in what he calls an “imponderable” quality, as opposed to its suspense or thrills. His poetic approach creates a sense of mystery and infuses an eeriness in the commonplace, achieved through a haunting and carefully applied aesthetic. Eugen Schüfftan, the cinematographer whose roots in German Expressionism include shooting Die Nibelungen (1924) and Metropolis (1927) for Fritz Lang, photographed the film. Schüfftan lights Scob in ways that transform her into a figurine or doll, while the actor’s gestures look gentle and wraithlike. The leisurely paced proceedings stretch over 90 minutes, offering few breaks from the patterned and straightforward presentation. Yet, composer Maurice Jarre’s hypnotic waltz introduces an uncanny, winding theme that emphasizes Christiane’s displacement from the normal world and highlights her eerie otherness. The film’s strangeness and powerful imagery lend the material to sweeping interpretation. Among the only positive French reviews from the film’s initial release, Bruno Gay-Lussac wrote in an issue of L’Express from March 10, 1960, that the film was “a fabulous story of modern mythology.” Critical and scholarly assessments have devised a wide array of interpretations, reading the film as a portrait of Nazi scientists, a feminist account of female subjugation in a patriarchal system, a commentary on the decline of natural beauty during post-World War II reconstruction, and a metaphor for colonial power in reflection of the Algerian War. None of these hypotheses could be called misguided, but some contain more in-film evidence than others.

Franju’s films often dwell on ideas of violence born out of everyday institutions. Before Eyes Without a Face, he made films that exposed the grim truth behind abattoirs, the military, and mental health facilities—all of which wear masks that conceal a horrific secret. Even his domestic drama Thérèse Desqueyroux (1962) seeks to peel away the mask of a provincial marriage to reveal something rotten underneath. Indeed, Franju’s films often engage in a process of unmasking for the sake of truth. “I believe there’s nothing but the truth,” he told an interviewer, “whether it’s beautiful or not, and consequently only the truth matters.” The visual symbolism of the mask, then, represents an expressionless prison for Christiane and a denier of truth. Génessier and Louise insist that she wears the mask, that she will grow “used to it,” but not for a medical reason. They conceal the fact that they have destroyed natural beauty—first in the car accident, and then in the subsequent murders in their efforts to restore Christiane’s face. But they ignore the human damage of the transplant, and how the physical and psychological scars will always remain beneath the surface.

Franju’s films often dwell on ideas of violence born out of everyday institutions. Before Eyes Without a Face, he made films that exposed the grim truth behind abattoirs, the military, and mental health facilities—all of which wear masks that conceal a horrific secret. Even his domestic drama Thérèse Desqueyroux (1962) seeks to peel away the mask of a provincial marriage to reveal something rotten underneath. Indeed, Franju’s films often engage in a process of unmasking for the sake of truth. “I believe there’s nothing but the truth,” he told an interviewer, “whether it’s beautiful or not, and consequently only the truth matters.” The visual symbolism of the mask, then, represents an expressionless prison for Christiane and a denier of truth. Génessier and Louise insist that she wears the mask, that she will grow “used to it,” but not for a medical reason. They conceal the fact that they have destroyed natural beauty—first in the car accident, and then in the subsequent murders in their efforts to restore Christiane’s face. But they ignore the human damage of the transplant, and how the physical and psychological scars will always remain beneath the surface.

Franju associates beauty with the natural state of things, with Nature itself, and Eyes Without a Face weighs the destruction of several natural states against scientific progress. It’s a theme that goes back to Shelley’s novel, and Doctor Frankenstein’s crime of tampering with the natural world to create an abomination. Eventually, Frankenstein’s corruption of Nature revisits him to exact vengeance. Likewise, Génessier’s crimes do not go unpunished: The daughter he so desperately tries to save loses her mind, turns on him, and disappears into the woods, representing what Franju calls “the true image of madness itself.” And, in a touch of poetic justice, Franju, ever sympathetic toward animals, allows Génessier’s caged dogs to attack their jailer in a flourish of Nature’s revenge. Even Louise, who feels indebted to Génessier for restoring her face—though the film never mentions the origin of her disfigurement—is portrayed as a faithful subject with a pearl choker, not unlike a dog collar. Christiane releases Louise from her imprisonment by stabbing her in the neck of all places, drawing attention to the spot where Louise has been restrained. In each case, the director demonstrates an overriding sympathy for victims of institutions that exert their symbolically violent power over others

Eyes Without a Face remains such an enduring classic because of its rich signification—its horror employs thematically haunted and evocative symbols of eyes, faces, and masks. Franju’s cultivation of this imagery stems from his fascination with the cinéma fantastique and its capacity to transform commonplace objects into manifestations of terror. Génessier’s unassuming mannerisms and clinical professionalism—especially when hidden behind the familiar appearance of a surgeon’s cap and mask, making him appear as “eyes without a face”—reveal the nightmarish potential of institutions. Although the film’s terror rests in the notion of losing one’s identity, Franju’s mistrust of institutions reminds us that behind every veneer resides the potential for something horrific, which is concealed, out of focus, or masked. Franju’s imagery and peculiar tone throughout Eyes Without a Face reinforce his focus on the face as an open and accessible site of truth, leaving any attempt to conceal, deny, or disfigure the face a crime against Nature. These elemental ideas rest at the film’s center, and their corruption leaves us thoroughly haunted.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your continued support, Ann!)

Bibliography:

Cashill, Robert. “Review: Eyes Without a Face.” Cinéaste, vol. 30, no. 3, 2005, pp. 74–75, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41689887. Accessed 15 November 2021.

Conrad, Randall, and Georges Franju. “Mystery and Melodrama: A Conversation with Georges Franju.” Film Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 2, University of California Press, 1981, pp. 31–42, https://doi.org/10.2307/1212048. Accessed 16 November 2021.

Durgnat, Robert. Franju. University of California Press, 1968.

Geroulanos, Stefanos. “Postwar Facial Reconstruction: Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face.” French Politics, Culture & Society, vol. 31, no. 2, 2013, pp. 15–33, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24517604. Accessed 15 November 2021.

Glasser, Brian. “Medical Classics: Eyes Without a Face.” BMJ: British Medical Journal, vol. 342, no. 7794, BMJ, 2011, pp. 445–445, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20839563. Accessed 15 November 2021.

Kalat, David. “Eyes Without a Face: The Unreal Reality.” Criterion.com, 16 October 2013, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/343-eyes-without-a-face-the-unreal-reality. Accessed 15 November 2021.

McGrath, Patrick. “Appearances to the Contrary: Eyes Without a Face.” Criterion.com, 15 October 2013, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/677-appearances-to-the-contrary-eyes-without-a-face. Accessed 15 2021.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review