The Definitives

Barton Fink

Essay by Brian Eggert |

“Look upon me! I’ll show you the life of the mind!” proclaims John Goodman’s character in Barton Fink, Joel and Ethan Coen’s masterful hermetic comedy from 1991 about a playwright and would-be screenwriter with writer’s block. The man who bellows this declaration runs down a fiery hotel hallway with a shotgun in hand. The moment horrifies the viewer in what until recently has been a darkly funny parody of Hollywood in the 1940s and a telling observation of the writer’s role in cinema. New York dramatist Barton Fink believes he has unique insight into the “life of the mind” because he’s a self-proclaimed creator whose latest deep-dish stage piece has earned some accolades. But once he moves to Hollywood to write for the pictures, he’s holed-up inside an empty, quiet hotel room, subject to the occasional sounds of neighbors distracting him to an all-consuming degree. The snobbish Fink—whose name is another word for a chatterbox—can do little more than stare at a hotel painting of a bathing beauty looking out at the ocean. Often bleakly funny and bittersweet, the fourth film by the offbeat brothers defies genre as many of their pictures do; it remains dreamlike, though it depicts the relatively straightforward subject of Hollywood’s long history of using up and alienating great writers. Arcane and symbolic, the film journeys into the life of the mind and finds all manner of humorous, mysterious, and even disturbing moments, yet resolves that the life of the mind alone is no place to live.

The household names that they are now, Joel and Ethan Coen did not always enjoy the equal measure of artistic and commercial success that they have today. Their widespread popularity did not come about until 1996 with their seminal work Fargo, followed by cult favorite The Big Lebowski (1998) and the universally celebrated O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2001). Their debut Blood Simple was released in 1984 to impressive reviews. Richard Corliss wrote in Time that their film was “A debut as scarifyingly original as anything since Orson Welles.” But neither Blood Simple, nor their subsequent two films, as brilliant as they are, achieved box-office success. Raising Arizona (1987) performed badly and would not grow in popularity for years to come, while Miller’s Crossing (1990) was ignored in theaters despite being named as one of the year’s best films by the National Board of Review. The reception of Barton Fink was no different, polarized between critical favor and audience rejection. It seemed to solidify the Coen Brothers as major artistic talents and win over those who believed their earlier work was no more than playful genre experiments. Their fourth film won several prizes at the Cannes Film Festival in 1991, including Best Actor for John Turturro, Best Director for Joel Coen, and the festival’s Palme d’Or—the first time in Cannes history these three awards were given to the same film. It’s worth noting that the Coens, despite a clear pattern of financial failures, did not yet change their method to achieve more commercially successful hits. They remained true to their art with these early pictures.

As for the division of labor, Joel and Ethan share equal credits in their newest films, but before No Country for Old Men (2007), Joel was the credited director and Ethan the producer, and they both received writing credit. In reality, the production process was far more flowing, with each brother contributing to directing and producing. Raised in a suburb of Minneapolis, Minnesota, the brothers’ parents were both college professors. Ethan went on to major in philosophy at Princeton, while Joel attended film school. Their friend and sometimes-collaborator Sam Raimi, whose breakout hit The Evil Dead (1979) Joel helped edit, described their collaboration by saying that Ethan has the literary mind and Joel has the visual mind. “We write together without parting company. We lock ourselves in a room and write the script from A to Z,” Joel told interviewers Michel Ciment and Hubert Niogret. “On the set it’s basically a continuation of the writing. We’re always there, both of us, and we consult each other continually. The credits indicate a division of labor more rigid than what really happens.” Joel continued, “To avoid confusion, I speak to the actors and communicate most of the time with the technical crew, but for the directing decisions it’s a mutual responsibility.”

As for the division of labor, Joel and Ethan share equal credits in their newest films, but before No Country for Old Men (2007), Joel was the credited director and Ethan the producer, and they both received writing credit. In reality, the production process was far more flowing, with each brother contributing to directing and producing. Raised in a suburb of Minneapolis, Minnesota, the brothers’ parents were both college professors. Ethan went on to major in philosophy at Princeton, while Joel attended film school. Their friend and sometimes-collaborator Sam Raimi, whose breakout hit The Evil Dead (1979) Joel helped edit, described their collaboration by saying that Ethan has the literary mind and Joel has the visual mind. “We write together without parting company. We lock ourselves in a room and write the script from A to Z,” Joel told interviewers Michel Ciment and Hubert Niogret. “On the set it’s basically a continuation of the writing. We’re always there, both of us, and we consult each other continually. The credits indicate a division of labor more rigid than what really happens.” Joel continued, “To avoid confusion, I speak to the actors and communicate most of the time with the technical crew, but for the directing decisions it’s a mutual responsibility.”

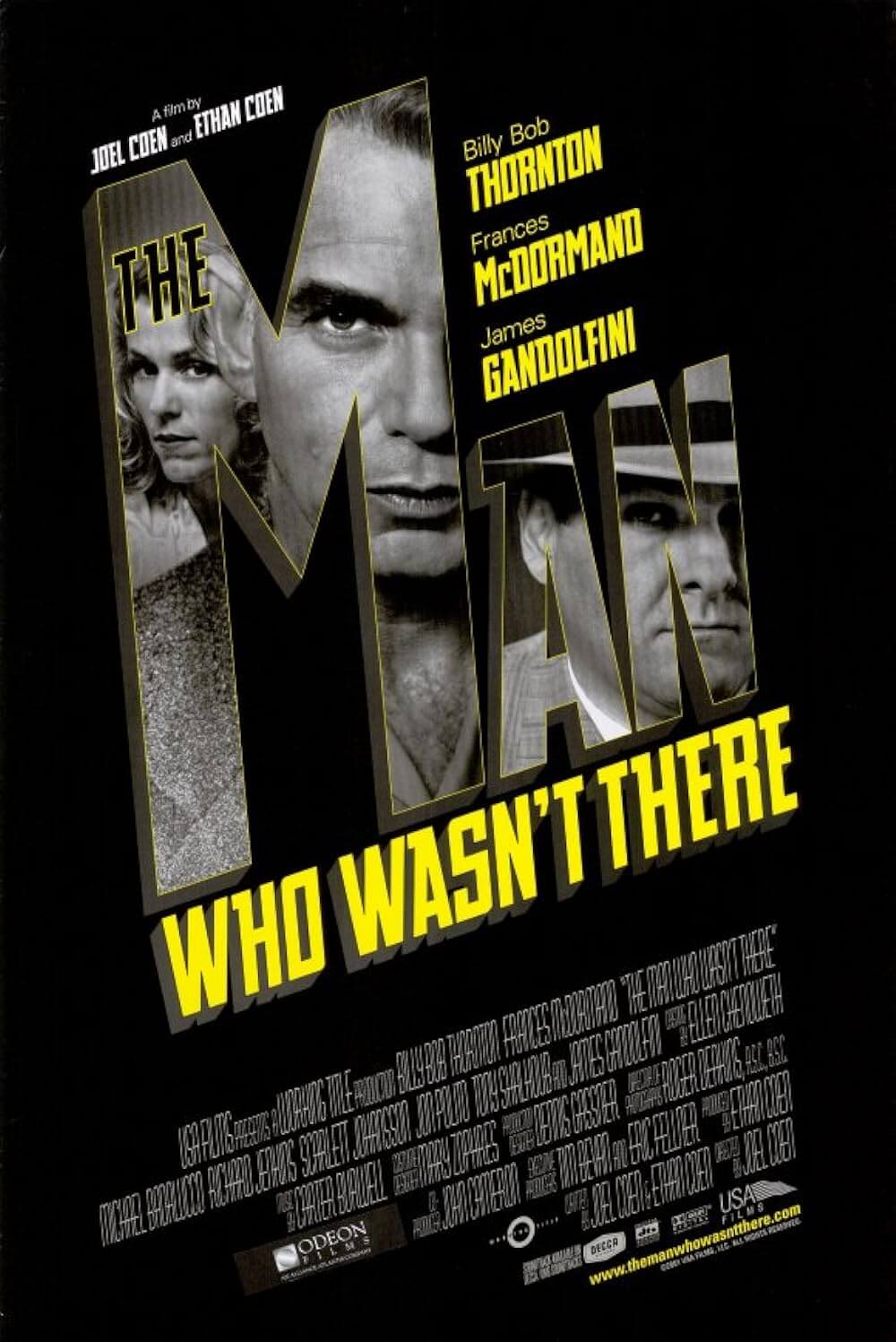

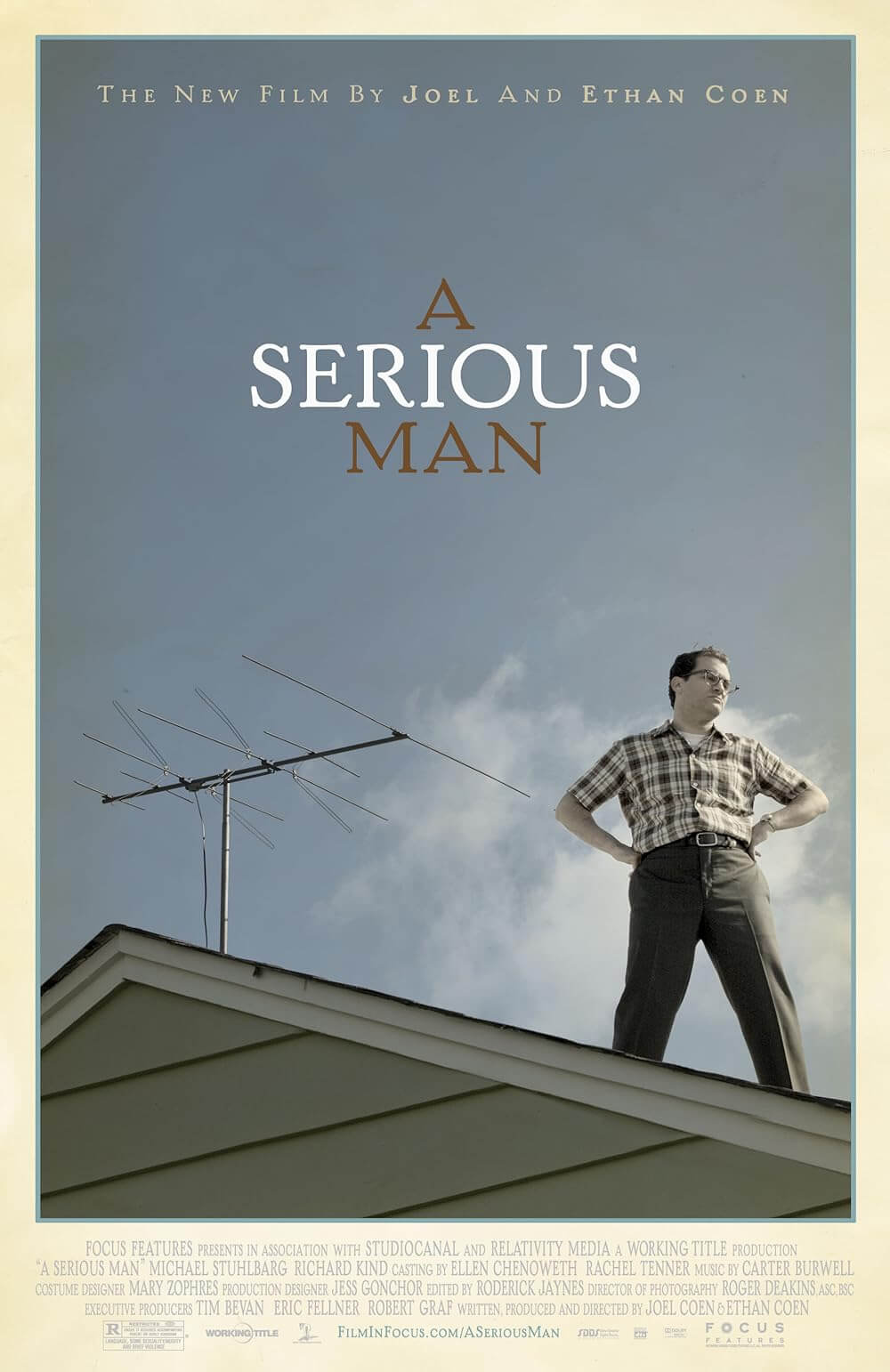

The Coens’ approach to filmmaking is extremely precise and self-conscious. “We storyboard out films like Hitchcock,” Joel told an interviewer. “There’s very little improvisation because we’re chicken basically.” Their fear of Raimi’s improvisational, uninhibited filmmaking leads to their own very deliberate, cerebral, and literary technique. However, both brothers experienced a severe case of writer’s block in the midst of writing Miller’s Crossing. To direct their attention elsewhere, Barton Fink was created as a form of therapy, being a story about a screenwriter with incurable writer’s block. “Barton Fink sort of washed out our brain and we were able to go back and finish Miller’s Crossing.” It’s surprising the Coens do not write themselves into a blockage more often, as their approach involves intentionally writing themselves into a corner if only to try and escape. Joel explained their approach to an interviewer: “Dream up horrible situations to put the characters through.” Ethan elaborated: “Make it worse.” The audience should be “the only privileged party to know what actually happened… The characters are still in the dark.” Certainly this description applies to several of the Coens’ films (Blood Simple, The Big Lebowski, etc.), and in some cases, their films have felt impenetrable even to their viewers (such complaints met A Serious Man, The Man Who Wasn’t There, and Inside Llewyn Davis).

Production on Barton Fink began in June of 1990 and wrapped in a mere eight weeks. Much like writing their script, the shoot was efficient regardless of the seemingly labored artistry that appears onscreen in the finished product. Their partnership with cinematographer Roger Deakins, who has shot the majority of the Coens’ films, began on Barton Fink. Their first three films were shot by Barry Sonnenfeld, who had since moved on to become a director himself. The Coens interviewed Deakins, admiring his work, and he accepted their offer, regardless of some mild protest by his agent. Deakins captured art director Dennis Gassner’s elaborate art deco sets to glorious, haunting effect, evoking the ghostly version of the Overlook Hotel from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. But their representation of the period should not be considered modern; the Coens are nothing if not post-modernists, embracing specific periods and places through their own unique, Coen-specific pastiche of varied influences. Consider the over-the-top performances, each character a familiar type exaggerated to hilarious and disturbing degrees by the cast. Turturro’s performance is fantastic; his Barton Fink is the effeminate child among the men of Hollywood. The actor is perfectly tuned even during the most over-the-top scenes. He’s also brilliant in the more inward scenes of writer’s block catatonia, his mouth agape, his eyes tired and dead, often in disbelief of his misfortune and misery. The same praise should be bestowed on the entire ensemble of wild performances. It’s a testament to the Coens that they can deliver such grandiose characters and still evoke an emotional response from the viewer.

Production on Barton Fink began in June of 1990 and wrapped in a mere eight weeks. Much like writing their script, the shoot was efficient regardless of the seemingly labored artistry that appears onscreen in the finished product. Their partnership with cinematographer Roger Deakins, who has shot the majority of the Coens’ films, began on Barton Fink. Their first three films were shot by Barry Sonnenfeld, who had since moved on to become a director himself. The Coens interviewed Deakins, admiring his work, and he accepted their offer, regardless of some mild protest by his agent. Deakins captured art director Dennis Gassner’s elaborate art deco sets to glorious, haunting effect, evoking the ghostly version of the Overlook Hotel from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. But their representation of the period should not be considered modern; the Coens are nothing if not post-modernists, embracing specific periods and places through their own unique, Coen-specific pastiche of varied influences. Consider the over-the-top performances, each character a familiar type exaggerated to hilarious and disturbing degrees by the cast. Turturro’s performance is fantastic; his Barton Fink is the effeminate child among the men of Hollywood. The actor is perfectly tuned even during the most over-the-top scenes. He’s also brilliant in the more inward scenes of writer’s block catatonia, his mouth agape, his eyes tired and dead, often in disbelief of his misfortune and misery. The same praise should be bestowed on the entire ensemble of wild performances. It’s a testament to the Coens that they can deliver such grandiose characters and still evoke an emotional response from the viewer.

Barton Fink is notoriously thorny for some views. A major clue to cracking the film is the character W.P. Mayhew, played by the mustachioed and bowtied John Mahoney. The Coens’ character Mayhew is a dead ringer for the older version of real-life writer William Faulkner, complete with a distinguished look behind pursed lips, silver hair, and dark mustache and eyebrows. Faulkner, like Mayhew, was an incurable alcoholic whose great promise as a writer was largely wasted in Hollywood, leaving his unfinished screenplays to be completed by his mistress, Meta Carpenter, a script girl for director and producer Howard Hawks and the spitting image of Mayhew’s long-suffering mistress Audrey Taylor (Judy Davis). And yet, images of a young Faulkner look suspiciously like Barton Fink as well, complete with a shabby but practical overcoat and vertical hair. (Admittedly, Barton looks more like Clifford Odets, the New York playwright whose socially minded plays earned him a ticket to Hollywood, where he contributed to screenplays such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946) and Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success(1957).) Like Fink, Faulkner was lured to Hollywood because of his success on the New York stage. Hawks enticed the writer to Tinsel Town after reading his story Turn About, as its themes of World War I aviation interested Hawks, who himself explored the subject in earlier films like Air Circus (1928) and later in Only Angels Have Wings (1939). Hawks purchased the rights to Turn About for $5,000 and wrangled Faulkner to adapt his own story for MGM.

Faulkner took a mere five days to adapt Turn About into a script, which Hawks loved but nonetheless demanded immediate rewrites to accommodate one of MGM’s contracted stars, Joan Crawford, who needed a new project. Faulkner’s initial draft did not have a role that suited Crawford; but the script could be rewritten to serve the studio, as screenplays often were. Contracted studio writers Dwight Taylor and Edith Fitzgerald were assigned to alter the script, and by the time they were finished, the title was changed to Today We Live and Faulkner was only credited for the dialogue and original story. Faulkner remains at the center of several tales about screenplay development like that of the transformation from Turn About to Today We Live, and he would continue to receive minor credits during his tenure in Hollywood, as well as many uncredited jobs as a script doctor. But unlike Mayhew in Barton Fink, Faulkner did not lose himself in drink and lose any hope of artistic integrity in cinema. Faulkner would go on to work on dozens of scripts for MGM, plus other studios like Warner Bros. and Fox (Jack Warner famously bragged he was “employing America’s best writer for peanuts”). Many of his works were classics, such as To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946), both of which were written for Hawks to direct.

Faulkner took a mere five days to adapt Turn About into a script, which Hawks loved but nonetheless demanded immediate rewrites to accommodate one of MGM’s contracted stars, Joan Crawford, who needed a new project. Faulkner’s initial draft did not have a role that suited Crawford; but the script could be rewritten to serve the studio, as screenplays often were. Contracted studio writers Dwight Taylor and Edith Fitzgerald were assigned to alter the script, and by the time they were finished, the title was changed to Today We Live and Faulkner was only credited for the dialogue and original story. Faulkner remains at the center of several tales about screenplay development like that of the transformation from Turn About to Today We Live, and he would continue to receive minor credits during his tenure in Hollywood, as well as many uncredited jobs as a script doctor. But unlike Mayhew in Barton Fink, Faulkner did not lose himself in drink and lose any hope of artistic integrity in cinema. Faulkner would go on to work on dozens of scripts for MGM, plus other studios like Warner Bros. and Fox (Jack Warner famously bragged he was “employing America’s best writer for peanuts”). Many of his works were classics, such as To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946), both of which were written for Hawks to direct.

Still, Faulkner’s journey to Hollywood undoubtedly served as a major influence for the Coens. When Faulkner first arrived in Hollywood in 1935, one of the first projects MGM producer Sam Marx assigned to the writer was a remake of The Champ (1931), the story of a boxer played by Wallace Beery. The remake, eventually called Flesh, would also star Beery, but the film’s protagonist would be a wrestler this time. Faulkner never completed the script (credited to Moss Hart). The story of Barton Fink is similar. Capitol Pictures sees that Barton is on the brink of success with his new play and his “creation of a new living theater of, for, and about the common man,” as Barton describes it. “The hopes and dreams of the common man are as noble as those of any king. It’s the stuff of life – why shouldn’t it be the stuff of theater?” And with the dreamlike transition of a wave crashing on a rock, Barton finds himself in Hollywood. The first project he’s given by fast-talking, bombastic studio head Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner) is not one of Barton’s socially relevant stories about everyday people living in hard times; rather, it’s a rewrite of a wrestling picture that’s to star Wallace Beery. The look of disappointment on Barton’s face when he’s asked to write a dull studio programmer is unmistakable. He’s asked to transfer “that Barton Fink feeling” to a wrestling picture of all things, resulting in a debilitating case of writer’s block. Still, he’s swept up by the prestige of writing for Hollywood, even if it conflicts with his artistic vision. He may search for “the stories of the common man,” but he ignores the common man by adhering to the expectations of his new Hollywood associates.

When Barton checks into the tired and empty Hotel Earle, an all but abandoned building that probably enjoyed some modest success in the 1920s, the peppy bellhop Chet (Steve Buscemi) brings Barton to his room for an indefinite stay—the hotel’s frightening motto, “A day or a lifetime.” It’s a shabby room filled with distractions. Brown water stains blotch the ceiling. The intolerable heat melts the oozing wallpaper glue and sheets begin to peel; Chet delivers tacks to Barton’s room so the sheets can be pinned up. Somewhere in his room buzzes a mosquito. And through his room’s thin walls he can hear his neighbors making love or, in the case of Charlie Meadows (John Goodman), the insurance salesman next door with the gift of gab, having heated conversations with himself. Barton even calls Chet to complain about Charlie’s noise, inciting Charlie to knock on Barton’s door and smooth things over with a drink. These distractions add to his already incapacitating writer’s block, born from impossible expectations set upon him. “We expect great things,” Lipnick told him. But as Barton sits in front of his typewriter, in front of the three sentences he was able to eke out over the course of several days, he wonders whether his play was just a flash in the pan, or if he actually has some real talent. Charlie tries to help, listening to Barton prattle on about “the life of the mind,” Barton’s self-important concept in which “the stuff of life” is transported to paper. Charlie puts forth, “I can tell you stories that would curl your hair,” but Barton doesn’t listen. He’s too caught up in his Living Theater diatribe, and the consequences are grim and frightening.

When Barton checks into the tired and empty Hotel Earle, an all but abandoned building that probably enjoyed some modest success in the 1920s, the peppy bellhop Chet (Steve Buscemi) brings Barton to his room for an indefinite stay—the hotel’s frightening motto, “A day or a lifetime.” It’s a shabby room filled with distractions. Brown water stains blotch the ceiling. The intolerable heat melts the oozing wallpaper glue and sheets begin to peel; Chet delivers tacks to Barton’s room so the sheets can be pinned up. Somewhere in his room buzzes a mosquito. And through his room’s thin walls he can hear his neighbors making love or, in the case of Charlie Meadows (John Goodman), the insurance salesman next door with the gift of gab, having heated conversations with himself. Barton even calls Chet to complain about Charlie’s noise, inciting Charlie to knock on Barton’s door and smooth things over with a drink. These distractions add to his already incapacitating writer’s block, born from impossible expectations set upon him. “We expect great things,” Lipnick told him. But as Barton sits in front of his typewriter, in front of the three sentences he was able to eke out over the course of several days, he wonders whether his play was just a flash in the pan, or if he actually has some real talent. Charlie tries to help, listening to Barton prattle on about “the life of the mind,” Barton’s self-important concept in which “the stuff of life” is transported to paper. Charlie puts forth, “I can tell you stories that would curl your hair,” but Barton doesn’t listen. He’s too caught up in his Living Theater diatribe, and the consequences are grim and frightening.

Barton searches for inspiration from Mayhew, but comes to realize this “great American writer” is no more than a sorry drunk whose mistress writes his material. Soon enough, Barton must answer for his would-be script. The Coens create a trio of Hollywood studio personalities that lighten this otherwise pitch-black comedy by a few shades. Tony Shaloub plays Barton’s producer, Ben Geisler, another fast-talker of the His Girl Friday variety, not unlike Shaloub’s lawyer character in The Man Who Wasn’t There. When Barton admits he’s having trouble getting started on the script, Geisler says flatly, “Wallace Beery. Wrestling picture. Whaddya need a roadmap?” Lerner’s hilariously motormouthed Jewish producer (who refers to himself as a “kike”) goes out of his way to humiliate his longtime assistant Lou Breeze (Jon Polito) to demonstrate his power in front of Barton, whom he’s “taken an interest in”, much to Barton’s dread. Under a bad comb-over and butlery mannerisms, Breeze used to be a major player in Hollywood, until he wasn’t. Will Barton end up like Breeze? That’s the fear. The night before he’s supposed to pitch his outline to Lipnick, Barton has no other choice; he calls Audrey to help. Instead of working on the script, however, they make love. When Barton wakes up the next morning, he sees the mosquito that has terrorized his room for days; it lands on the sleeping Audrey and begins to feed. When he slaps it, he kills the mosquito but Audrey doesn’t react. Barton tries to nudge her awake, and then a thick pool of blood seeps from under her body onto the sheets. All Barton can do is scream.

During an interview, Joel Coen was once quoted as saying, “Roman Polanski is a favorite. He’s terrific. Knife in the Water, Repulsion, The Tenant, Chinatown, Rosemary’s Baby—I love them all.” Known for his internal characters and nightmarish situations that sometimes occur only in his protagonist’s head, Polanski remains an obvious influence on Barton Fink, in particular Repulsion and The Tenant. Both films are about a lone character experiencing some kind of internal nightmare, exacerbated by their self-imposed solitude in a single apartment. For Barton, that nightmare is how he’s unable to articulate some meaningful drama out of life’s chaos, augmented by his rundown room and the boundless expectations set upon him. Polanski himself couldn’t have made a more paranoid, surreal situation for Barton after the character discovers Audrey dead. Cue Charlie, Barton’s good-natured neighbor at the Earle. Ironically, Barton’s story is right in front of him, with Charlie standing in as a boorish wrestler and Barton, with his effeminate traits (from his noodly walk to his frantic screams, to how Audrey lays him down before they make love) as the dame. Charlie hears Barton screaming and rushes over, sees the bloody mess, and somehow stays calm enough to take care of the body for his friend. He tells Barton that he’ll take care of everything. Later, Barton must go to his meeting with Lipnick, where he sits, almost catatonic from the events of the morning. By the meeting’s end, Lipnick literally gets down on his knees and kisses the bottom of Barton’s shoe to demonstrate his respect for the writers of Capitol Pictures, as Barton refuses to discuss details of his nonexistent script for reasons of artistic integrity.

During an interview, Joel Coen was once quoted as saying, “Roman Polanski is a favorite. He’s terrific. Knife in the Water, Repulsion, The Tenant, Chinatown, Rosemary’s Baby—I love them all.” Known for his internal characters and nightmarish situations that sometimes occur only in his protagonist’s head, Polanski remains an obvious influence on Barton Fink, in particular Repulsion and The Tenant. Both films are about a lone character experiencing some kind of internal nightmare, exacerbated by their self-imposed solitude in a single apartment. For Barton, that nightmare is how he’s unable to articulate some meaningful drama out of life’s chaos, augmented by his rundown room and the boundless expectations set upon him. Polanski himself couldn’t have made a more paranoid, surreal situation for Barton after the character discovers Audrey dead. Cue Charlie, Barton’s good-natured neighbor at the Earle. Ironically, Barton’s story is right in front of him, with Charlie standing in as a boorish wrestler and Barton, with his effeminate traits (from his noodly walk to his frantic screams, to how Audrey lays him down before they make love) as the dame. Charlie hears Barton screaming and rushes over, sees the bloody mess, and somehow stays calm enough to take care of the body for his friend. He tells Barton that he’ll take care of everything. Later, Barton must go to his meeting with Lipnick, where he sits, almost catatonic from the events of the morning. By the meeting’s end, Lipnick literally gets down on his knees and kisses the bottom of Barton’s shoe to demonstrate his respect for the writers of Capitol Pictures, as Barton refuses to discuss details of his nonexistent script for reasons of artistic integrity.

Nevertheless, our writer does achieve a few moments of clarity. When Barton returns home, Charlie explains he’ll be out of town in New York for a few days. Barton gives Charlie his family’s address and recommends stopping for some hospitality and a good meal; Charlie gives Barton a wrapped and tied box and asks him to hold it until he returns. Sometime later, Barton receives a visit at the Earle from two detectives who inform him that Charlie is really Karl “Madman” Mundt, a mass murderer who kills with a double-barrel shotgun and removes the heads of his victims. Though the film never asks the question itself, we must wonder, Did Charlie put someone’s head the box he gave Barton? Despite all of this, and with his blood-soaked mattress to his back, Barton finds an uncommon artistic lucidity. He punches out a script in a matter of days. It’s genius, and he knows it. He goes out to celebrate its completion with a dance at a local USO hall—a little too enthusiastically, as it turns out. The sailors want him off the dance floor; he’s hogging a young female dance partner. Barton reacts abominably, shouting that he deserves to dance because “I create, I am a creator!” Nevermind that the date is December 9, 1941, just two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Barton has no consideration for soldiers; he points to his head, “This is my uniform!”

The final scenes of Barton Fink are as strange, frightening, and enigmatic, and further elucidate the Coens’ work on this picture as Polanski-esque. Artistically trapped, Barton returns to his room in the Earle where he’s visited again by the two detectives chasing Mundt. They see Barton’s mattress stained in dried blood and, assuming he’s an accomplice, handcuff him to the bedframe. All at once, “Charlie” arrives in the elevator down the hall; like some hellish nightmare, the hallway walls goes up in flames. Charlie charges at the detectives and shoots them down. But when he shouts throughout the killing, he directs his decree to Barton: “I’ll show you the life of the mind!” Amid the blaze, Barton and Charlie have a curious conversation where the killer explains the reason for the bloodshed and fire: “You don’t listen!” At that moment, puss gushes down from Charlie’s ears, recalling the glue that oozed from the peeling wallpaper in Barton’s room. “People can be so cruel,” he reflects. But Charlie doesn’t kill Barton. He pulls apart the gate of the bedframe, freeing him, and returns to his room, likely to die in the blaze. Barton, eerily calm in the fire, takes his script and the box Charlie left him. He arrives at Capitol Pictures and tries calling home to confirm his family is still alive after Charlie’s visit, but there’s no answer. Then he meets with Lipnick about his On the Waterfront of wrestling pictures. But Lipnick rejects his script; the studio wanted a B-picture, not some “fruity” work. Lipnick, donning a faux admiral costume in anticipation of his Army reserve commission, announces Barton will remain under contract with Capitol Pictures until he can “grow up”—his artistry ostensibly owned before it’s written. Lipnick tells him he’s “not a writer… You’re a write-off.” Faulkner comes to mind.

The final scenes of Barton Fink are as strange, frightening, and enigmatic, and further elucidate the Coens’ work on this picture as Polanski-esque. Artistically trapped, Barton returns to his room in the Earle where he’s visited again by the two detectives chasing Mundt. They see Barton’s mattress stained in dried blood and, assuming he’s an accomplice, handcuff him to the bedframe. All at once, “Charlie” arrives in the elevator down the hall; like some hellish nightmare, the hallway walls goes up in flames. Charlie charges at the detectives and shoots them down. But when he shouts throughout the killing, he directs his decree to Barton: “I’ll show you the life of the mind!” Amid the blaze, Barton and Charlie have a curious conversation where the killer explains the reason for the bloodshed and fire: “You don’t listen!” At that moment, puss gushes down from Charlie’s ears, recalling the glue that oozed from the peeling wallpaper in Barton’s room. “People can be so cruel,” he reflects. But Charlie doesn’t kill Barton. He pulls apart the gate of the bedframe, freeing him, and returns to his room, likely to die in the blaze. Barton, eerily calm in the fire, takes his script and the box Charlie left him. He arrives at Capitol Pictures and tries calling home to confirm his family is still alive after Charlie’s visit, but there’s no answer. Then he meets with Lipnick about his On the Waterfront of wrestling pictures. But Lipnick rejects his script; the studio wanted a B-picture, not some “fruity” work. Lipnick, donning a faux admiral costume in anticipation of his Army reserve commission, announces Barton will remain under contract with Capitol Pictures until he can “grow up”—his artistry ostensibly owned before it’s written. Lipnick tells him he’s “not a writer… You’re a write-off.” Faulkner comes to mind.

And while ending the picture there might have connected back to the conclusion of Blood Simple by being a cruel punchline on the protagonist, the final moment of Barton Fink has more in common with the uncertain, searching feeling at the end of Raising Arizona, or later in The Man Who Wasn’t There and A Serious Man. After seeing Lipnick, Barton visits Zuma Beach and sits in the sand. A woman sits down in front of him. He tells her that she should be in the pictures, and then they both look out at the ocean. This final shot of the film recalls the painting in Barton’s room at the Earle, an impossible fantasy. Some might argue that all of Barton Fink takes place in those first days where Barton settles into his room, and our writer imagines the film’s entire scenario when he loses himself in the painting of the girl on the beach. Then again, perhaps the answer lies in the repressed rage of the common man—which Barton so fervently believes he understands, and which has snapped back and bit him on the nose—has consumed him. All Barton can do is contemplate what it all means, if anything. Does he even realize he’s sitting in a scene identical to the painting? To be sure, the Coens playfully and symbolically engage the relationship between fantasy and reality, between art and life, between the life of the mind and the real world.

Ever readable, Barton Fink mixes a fascinating potion of isolation, paranoia, and anxiety, as well as a harsh dose of uncertainty for our unfortunate writer. On the surface, the picture reveals the internalized writing process as a maze of influences both real and imagined; elsewhere, the film satirizes Hollywood’s treatment of writers as comically mordant and cruel. But underneath, the filmmakers avoid anything resembling a straightforward film, more so even than their earlier works. As ever with the Coen brothers’ characters, Barton Fink searches for meaning and finds no answers; rather, the world that he thought he understood, and even controlled, is dismantled piece by piece by his own artist’s ego. When Lipnick tells Barton, “You think you’re the only writer that can give me that ‘Barton Fink feeling’?” our writer’s identity is stripped away. In that sense, the film reaches far beyond its outward subject and prods the audience with an existential stick, asking us if we or their characters are still alive inside. Whether the viewer determines the film as a depiction of artistic growth or another of their searches for meaning where there’s none to find, the rich technique and experience is beguiling, intriguing, unforgettable. It checks into a room in the viewer’s brain and stays there indefinitely, for a day or a lifetime.

Ever readable, Barton Fink mixes a fascinating potion of isolation, paranoia, and anxiety, as well as a harsh dose of uncertainty for our unfortunate writer. On the surface, the picture reveals the internalized writing process as a maze of influences both real and imagined; elsewhere, the film satirizes Hollywood’s treatment of writers as comically mordant and cruel. But underneath, the filmmakers avoid anything resembling a straightforward film, more so even than their earlier works. As ever with the Coen brothers’ characters, Barton Fink searches for meaning and finds no answers; rather, the world that he thought he understood, and even controlled, is dismantled piece by piece by his own artist’s ego. When Lipnick tells Barton, “You think you’re the only writer that can give me that ‘Barton Fink feeling’?” our writer’s identity is stripped away. In that sense, the film reaches far beyond its outward subject and prods the audience with an existential stick, asking us if we or their characters are still alive inside. Whether the viewer determines the film as a depiction of artistic growth or another of their searches for meaning where there’s none to find, the rich technique and experience is beguiling, intriguing, unforgettable. It checks into a room in the viewer’s brain and stays there indefinitely, for a day or a lifetime.

Bibliography:

Baz Allen, William Rodney, ed. The Coen Brothers: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

Bergan, Ronald. The Coen Brothers. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2000.

Coen, Joel and Ethan Coen. Barton Fink & Miller’s Crossing. London: Faber and Faber, 1991.

Dunne, Michael. “Barton Fink, Intertextuality, and the (Almost) Unbearable Richness of Viewing”. Literature/Film Quarterly 28.4 (2000). pp. 303–311.

Palmer, R. Barton. Joel and Ethan Coen. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Rowell, Erica. The Brothers Grim: The Films of Ethan and Joel Coen. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2007.

Woods, Paul A., ed, Joel and Ethan Coen: Blood Siblings. London: Plexus, 2000.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review