The Definitives

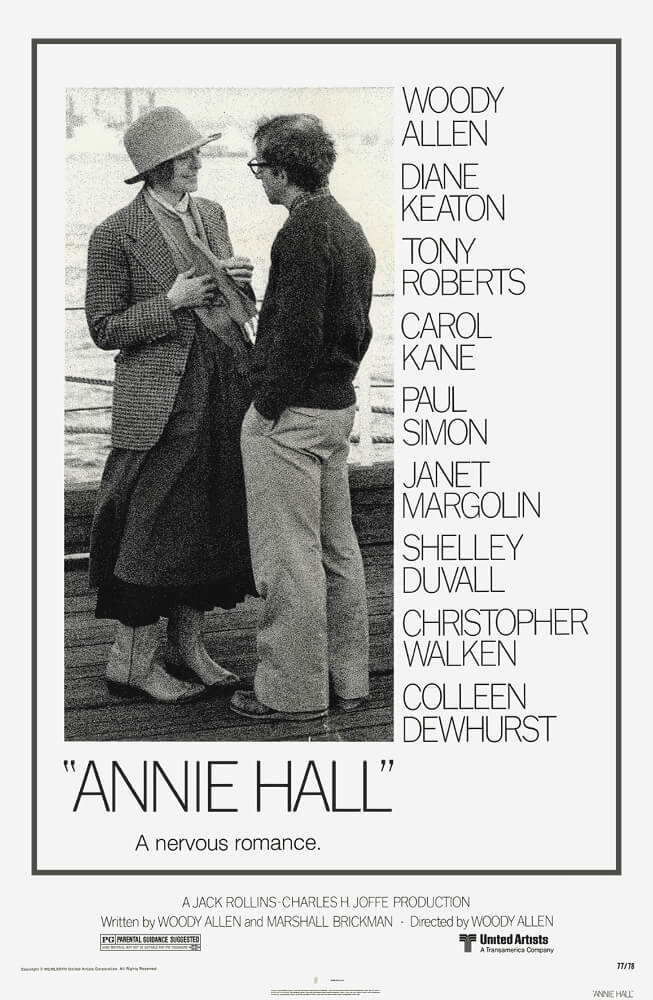

Annie Hall

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Few films are as funny and heartbreakingly true, but also as immeasurably creative as Annie Hall, Woody Allen’s sentiment on our pursuit and nostalgia for romantic relationships, however fleeting. Released in 1977, the film was a breakthrough for Allen and demonstrated how far his talents had matured in a relatively short span of time—from his emergence as a two-bit comic writer into a famed television personality, then into a successful director of broad comedies. With this film, Allen surfaced as a sophisticated storyteller and filmmaker. His comic persona, that neurotic intellectual whose anxieties are hilariously exaggerated for effect, cultivates here into that of an artist who, while making us laugh with his signature wit, also discovers the ubiquitous life lesson running through many of Allen’s films: that even the most temporary of loves makes life, dreadful and cruel as it may sometimes be, worth living. Amid Allen’s north of forty films—his novelistic ensembles, his arty comedies, his comic trifles, his Bergmanesque dramas, his tales of murder and paranoia, and his occasional failures—Annie Hall is the one audiences return to most, perhaps because it remains his most affecting and accessible.

Released to surging box-office attendance and radical critical assessments that confirmed Allen had expanded the limitations of the comedy, Annie Hall earned back quadruple its meager $10 million budget and managed to steal the top Oscars (including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Actress) from under the nose of George Lucas’ iconic popular favorite Star Wars. But Allen’s film is iconic in its own way that goes further than mere commercial sensation; it contains scenes that inspire us to reminisce about and quote them. Before Allen’s film, comedies were more often bright and airy and without consequence. They were more concerned about setting up the next joke than emotionally investing the audience in characters or in a narrative, or using intellectual references to illustrate complex witticisms. With Annie Hall, Allen not only elevated comedy to new heights, but he established a lasting presence in cinema, a presence whose features would outline what it meant to be an archetypal “Woody Allen film”.

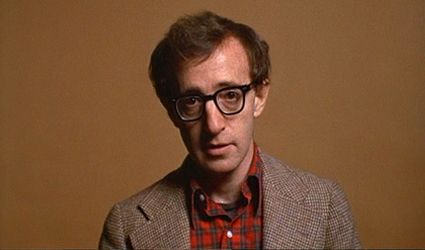

If his earlier stand-up work and comedies had not already done so, this film also delineates Allen’s lasting onscreen persona, both as an actor and a director. Allen surfaces as that interminable New Yorker whose Jewish upbringing provides the background to his nebbish manner and agnostic views, while his liberal and intellectualist self-education informs his cynicism. Disgusted by the lows of humanity and human history, he often finds himself bewildered by the whimsical ways in which life sometimes plays itself out. All his sexual insecurities and pervading fear of death are contrasted by an unshakable romantic appreciation of life. As his roles transform from film to film, these characteristics remain Allen’s, making each work, some more than others, autobiographical in the sense that his films have a distinct authorship that more often than not aligns with his subject. To be sure, Annie Hall is as much a tale of love between Allen’s comic character Alvy Singer and Diane Keaton’s lounge singer Annie Hall as it is about Woody Allen.

If his earlier stand-up work and comedies had not already done so, this film also delineates Allen’s lasting onscreen persona, both as an actor and a director. Allen surfaces as that interminable New Yorker whose Jewish upbringing provides the background to his nebbish manner and agnostic views, while his liberal and intellectualist self-education informs his cynicism. Disgusted by the lows of humanity and human history, he often finds himself bewildered by the whimsical ways in which life sometimes plays itself out. All his sexual insecurities and pervading fear of death are contrasted by an unshakable romantic appreciation of life. As his roles transform from film to film, these characteristics remain Allen’s, making each work, some more than others, autobiographical in the sense that his films have a distinct authorship that more often than not aligns with his subject. To be sure, Annie Hall is as much a tale of love between Allen’s comic character Alvy Singer and Diane Keaton’s lounge singer Annie Hall as it is about Woody Allen.

Born in 1935 in The Bronx, Allen was originally named Allan Stewart Konigsberg, and as early as 1952 adopted the name “Woody Allen” when he sent in jokes and one-liners to local newspapers to be published under this pseudonym, and then legally changed his name to Heywood Allen. Raised by a stringent mother in a home not unlike the one depicted in the film, Allen escaped on a steady diet of jazz music and films playing in the half-dozen local moviehouses within walking distance from his home. He was influenced in his comic wit by screen idols like the Marx Brothers and Bob Hope, and stand-up comics such as Mort Sahl; in his teens he discovered his first foreign film, Ingmar Bergman’s Summer with Monika (1953), and later developed an affinity for other international filmmakers, such as Federico Fellini and Akira Kurosawa. When he was still in high school, Allen’s jokes had made their way into the material of Sid Ceasar, Phil Silvers, and Peter Lind Hayes, and he was making more than both his parents combined. He soon signed with talent agents Jack Rollins and the late Charles H. Joffe, who pressured Allen to break from writing-only into a stand-up routine, and eventually television. When Allen conceded, comic writer and friend Mike Merrick inspired his bespectacled look, and Allen’s black-rimmed frames have remained a signature ever since.

During this time, Allen briefly attended New York University and the City College of New York, studying communication and film, but found the college system was arbitrary when his professors flunked him for instilling humor into his papers. He admitted that to meet the intellectual women to whom he was most attracted, he read Faulkner and Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky and listened to Beethoven, and soon developed his own taste for more cerebral material than his usual string of comic books. After a rocky start in the Greenwich Village comic scene, Allen became a household name through his brainy and hilarious television work, first writing sketches for The Ed Sullivan Show, then appearing regularly on The Dick Cavett Show, and later as a frequent guest-host for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show and on his own comedy specials. His style was filled with wit, and like his films, his subjects revolved around sex, religion, and relationships, specializing in hilarious one-liners: “Basically my wife was immature. I’d be at home in my bath and she’d come in and sink my boats.” Yet, even at this early stage his work was fuelled by existential questioning and his signature fear of death: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work. I want to achieve it through not dying.” During his time as a stand-up comic, he began writing short stories and comic pieces for The New Yorker magazine and in turn defined himself as an intellectual humorist. But until the release of Annie Hall, his films would remain products of pure comic intent.

During this time, Allen briefly attended New York University and the City College of New York, studying communication and film, but found the college system was arbitrary when his professors flunked him for instilling humor into his papers. He admitted that to meet the intellectual women to whom he was most attracted, he read Faulkner and Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky and listened to Beethoven, and soon developed his own taste for more cerebral material than his usual string of comic books. After a rocky start in the Greenwich Village comic scene, Allen became a household name through his brainy and hilarious television work, first writing sketches for The Ed Sullivan Show, then appearing regularly on The Dick Cavett Show, and later as a frequent guest-host for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show and on his own comedy specials. His style was filled with wit, and like his films, his subjects revolved around sex, religion, and relationships, specializing in hilarious one-liners: “Basically my wife was immature. I’d be at home in my bath and she’d come in and sink my boats.” Yet, even at this early stage his work was fuelled by existential questioning and his signature fear of death: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work. I want to achieve it through not dying.” During his time as a stand-up comic, he began writing short stories and comic pieces for The New Yorker magazine and in turn defined himself as an intellectual humorist. But until the release of Annie Hall, his films would remain products of pure comic intent.

Having achieved fame and financial stability, Allen entered the film industry to find some kind of artistic success. He went into his first film projects with hopes of developing a standard, consistent comic persona onscreen, analogous to those of Bob Hope or Charlie Chaplin. And his desire for control over his own career was further justified by his early creative disasters in Hollywood. Allen’s first script for Charles K. Feldman’s production of What’s New, Pussycat? (1965) may have been a big break, but Allen’s words were butchered by the Hollywood process. He was hired to rewrite an existing script called “Lot’s Wife” and, after penning a role for himself, he watched as the production transformed into something other than what he had written. Other writers injected broad slapstick and laughs into his heady screen story and directors Clive Donner and Richard Talmadge took considerable liberties with the script’s tone. In 1966, Allen released What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, in which he and his friends provided a dubbed English dialogue into a Japanese-language film; although profitable, Allen later regarded the project as juvenile.

After, in 1967, Allen was asked to participate as an actor in a comic spoof on Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale. Though Allen’s scenes were few, the studio asked him to fly to London to participate in the shoot. They put him up in a hotel, and for 6 months he waited to shoot his scenes. During his considerable downtime, he wrote his play Don’t Drink the Water and lamented how un-productive a period it was. For his next film, Take the Money and Run (1969), Allen wanted more control to avoid an experience relative to those on What’s New, Pussycat? and Casino Royale. He worked from an original script, starred, and directed a picture that earned a hefty profit, and in the process he learned how little he knew about film production. Still, the film was a box-office hit and suggested to studio execs that Allen could be a profitable filmmaker. And so, after this series of movie writing and acting gigs that left him sour toward Hollywood yet in-demand, going forward Allen’s contract with studios stipulated a complete and unprecedented autonomy and artistic control the lengths to which no other filmmaker in the history of cinema would achieve or retain for as long as Allen has. His standard deal with his various studios over the years includes absolute control over the material, final cut, and approval over all marketing decisions.

After Take the Money and Run, Allen followed with a series of outright comedies that, for all intents and purposes, transfigured his stand-up routine into comic dialogue and narrative. He retained his so desired artistic control over each film, in which he wrote, directed, and starred. Bananas (1971) follows Allen’s character as he tries to impress his activist girlfriend by leading a revolution in a fictional South American country. His 1972 film, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask), pokes fun at Dr. David Reuben’s same-name book through a series of comic episodes. Sleeper (1973) was to be an ambitious 3-hour film that followed a New Yorker’s life during the first half, at which point he would be frozen and then wake up in the future; the final film consisted of just the future story. Allen satirized Russian literature from Dostoyevsky to Tolstoy in Love and Death (1975), and therein touched on themes and Bergman references he would explore more seriously in his future works. He also appeared in movies that he did not direct, such as Herbert Ross’ film of Allen’s own stage play, Play It Again, Sam (1972), and the McCarthyism dramedy The Front (1976).

After Take the Money and Run, Allen followed with a series of outright comedies that, for all intents and purposes, transfigured his stand-up routine into comic dialogue and narrative. He retained his so desired artistic control over each film, in which he wrote, directed, and starred. Bananas (1971) follows Allen’s character as he tries to impress his activist girlfriend by leading a revolution in a fictional South American country. His 1972 film, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask), pokes fun at Dr. David Reuben’s same-name book through a series of comic episodes. Sleeper (1973) was to be an ambitious 3-hour film that followed a New Yorker’s life during the first half, at which point he would be frozen and then wake up in the future; the final film consisted of just the future story. Allen satirized Russian literature from Dostoyevsky to Tolstoy in Love and Death (1975), and therein touched on themes and Bergman references he would explore more seriously in his future works. He also appeared in movies that he did not direct, such as Herbert Ross’ film of Allen’s own stage play, Play It Again, Sam (1972), and the McCarthyism dramedy The Front (1976).

In his films up to 1976, Allen’s unadorned approach resulted in brightly lit, plainly shot comedies with few technical flourishes to speak of. Their concentration falls on comedy, as opposed to the formal techniques in film-making. The lavish opening titles on Bananas contrast his later work, giving way to Allen’s simple, unornamented titles usually set to an old-time tune, often jazz music. Audiences in 1977 could immediately see that Annie Hall was different. Here, Allen’s now-standard black and white titles have no music at all to accompany them. The titles pass and the first shot consists of Woody Allen’s Alvy Singer breaking “the fourth wall” by speaking directly to the audience, almost stand-up style. He outlines his disparaging philosophy on life (“Full of loneliness and misery and suffering and unhappiness, and it’s all over much too quickly.”), and explains his self-deprecating, pessimistic views of himself (“I would never wanna belong to any club that would have someone like me for a member.”). And then he admits why we are here: “Annie and I broke up,” he confesses. “I keep sifting the pieces of the relationship through my mind and examining my life and trying to figure out where did the screw-up come.”

What results from this opening is an impressionistic structure where, told from Alvy’s perspective as he remembers, the film explores a love story through the lens of memory. Jumbled, perhaps even ill-remembered events play out in a hazy structure that allows Allen, as director and storyteller, to explore the limits of the medium as he has used it. Annie Hall was originally conceived as a period piece in which the protagonist suffered from Anhedonia, a condition where the victim cannot experience pleasure (this was also the original title of the film). Allen, along with his fellow cabaret performer and co-writer Marshall Brickman, then transferred the characters into a contemporary setting where Annie and Alvy investigate a murder mystery; they opted to scrap this idea for a less gimmicky exploration of love and relationships. (This murder concept was later revisited as Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993), and reunited Allen and Keaton for the last time.) Allen and Brickman’s writing process consisted of story forming sessions where the two would discuss how the script should proceed; Brickman would then leave and Allen would complete the actual writing.

What results from this opening is an impressionistic structure where, told from Alvy’s perspective as he remembers, the film explores a love story through the lens of memory. Jumbled, perhaps even ill-remembered events play out in a hazy structure that allows Allen, as director and storyteller, to explore the limits of the medium as he has used it. Annie Hall was originally conceived as a period piece in which the protagonist suffered from Anhedonia, a condition where the victim cannot experience pleasure (this was also the original title of the film). Allen, along with his fellow cabaret performer and co-writer Marshall Brickman, then transferred the characters into a contemporary setting where Annie and Alvy investigate a murder mystery; they opted to scrap this idea for a less gimmicky exploration of love and relationships. (This murder concept was later revisited as Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993), and reunited Allen and Keaton for the last time.) Allen and Brickman’s writing process consisted of story forming sessions where the two would discuss how the script should proceed; Brickman would then leave and Allen would complete the actual writing.

Allen’s intentions were to deepen his work, to move away from “just clowning around” and explore his own philosophical views in a more sophisticated approach, both narratively and formally. To ensure his production would be set apart from his earlier films, he hired Gordon Willis as his cinematographer. Known as “The Prince of Darkness” and renowned for his work on All the President’s Men and Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather films, Willis uses visual textures and a dark palette not traditionally associated with comedies, and through his efforts gave Annie Hall a distinct visual style, not just within Allen’s work up to this point, but for comedies in general. Allen and Willis would collaborate several times over the next decade on almost every film between Interiors (1978) and The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). Allen later commented, “My maturity in my films began with Gordon Willis. The films I made before Gordon were, I think, fun and exuberant and the best I could do. But I didn’t really know what I was doing, I was just learning… But it was not until later, when I did Annie Hall, that I became more ambitious and started to use the cinema.”

Revisiting the film, one is amazed by the range of techniques and devices Allen uses to enrich the material: spilt-diopter lenses; an animated sequence that incorporates Allen’s popular cartoon caricature from Inside Woody Allen, drawn by Stuart Hample, into a Snow White and the Seven Dwarves-type world; (the illusion of) split-screens; subtitles that convey thoughts; and a scene where Annie’s transparent soul steps out of herself during sex. Flashbacks enlighten the characters while impossible breaks from reality play to the audience. At one point early in the film, standing in line at the movies with Annie, Alvy complains about a patron behind him waxing intellectual about Fellini and media scholar Marshall McLuhan; Alvy turns to argue with the man about his preaching until he steps offscreen to produce who else but McLuhan himself, who tells the man, “You know nothing of my work.” Bending reality through comic wit and romantic circumstance, the film uses Alvy’s perspective to give a subjective account of how we distort and aggrandize our memories of love.

Revisiting the film, one is amazed by the range of techniques and devices Allen uses to enrich the material: spilt-diopter lenses; an animated sequence that incorporates Allen’s popular cartoon caricature from Inside Woody Allen, drawn by Stuart Hample, into a Snow White and the Seven Dwarves-type world; (the illusion of) split-screens; subtitles that convey thoughts; and a scene where Annie’s transparent soul steps out of herself during sex. Flashbacks enlighten the characters while impossible breaks from reality play to the audience. At one point early in the film, standing in line at the movies with Annie, Alvy complains about a patron behind him waxing intellectual about Fellini and media scholar Marshall McLuhan; Alvy turns to argue with the man about his preaching until he steps offscreen to produce who else but McLuhan himself, who tells the man, “You know nothing of my work.” Bending reality through comic wit and romantic circumstance, the film uses Alvy’s perspective to give a subjective account of how we distort and aggrandize our memories of love.

The film follows Alvy as he remembers his relationship with Annie, its heights and gradual decline, and at the same time acts as a platform for Allen’s most reoccurring themes and concerns. As Alvy’s memories pour out in an attempt to understand how he could let Annie slip away, he recalls his upbringing and past marriages, how he and Annie met, and questions the nature of love. Perhaps their breakup was, unconsciously, somehow impelled by a collision of his Jewish upbringing and Annie’s anti-Semitic grandmother (based on Keaton’s actual Grammy Hall), but then such a notion is probably fuelled by Alvy’s paranoia about anti-Semitism (leading to multiple viewings of The Sorrow and the Pity). Little of this occurs in chronological order, and few scenes take place within what we would call reality. Instead, call it memory. The film’s structure paints a fragmented picture, where narrative and Alvy’s philosophy merge, and yet each component is carefully placed. Alvy breaks out of his own story, as he had done with McLuhan, to consult bystanders in the scene or speak with the audience. He dwells on his preoccupation with mortality and his pessimism for humanity: “I feel that life is divided into the horrible and the miserable. That’s the two categories. The horrible are like, I don’t know, terminal cases, you know, and blind people, crippled… And the miserable is everyone else. So you should be thankful that you’re miserable.” But perhaps Annie left because of Alvy’s aversion to commitment. After all, Annie compares him to New York City—an island unto himself.

The film’s arrangement consists of scenes that propel the story and scenes that expound Alvy’s mindset, and together they feel like the inner workings of someone replaying and second-guessing their past in their head, making sense of some instances and left completely baffled by others. Moments of joy arise, such as when Alvy and Annie attempt to boil lobster or when Annie calls him over in the middle of the night to kill a spider after they have broken up. But also there are times when Alvy pushes Annie away; when she goes to California to record music with a stylish producer (Paul Simon), Alvy rejects that lifestyle for its lack of New York’s cosmopolitanism. Alvy (and Allen) thrives on walking down city sidewalks and talking—always in Allen’s stylized but oddly natural dialogue. His main characters talk to each other and their friends and their shrinks; they talk during racquetball, after sex, during a meal, and to the camera. Driven by dialogue captured in long takes, the film is as much a cross-section of Alvy’s life as is it an odyssey into Allen’s mind and heart. Through the film’s dialogue, the audience gathers a sense of Allen’s autobiographical strokes that, while embellished for the sake of comedy and romantic tragedy, paints a picture of memory and love and self-obsession that remains undeniable and universally true.

The film’s arrangement consists of scenes that propel the story and scenes that expound Alvy’s mindset, and together they feel like the inner workings of someone replaying and second-guessing their past in their head, making sense of some instances and left completely baffled by others. Moments of joy arise, such as when Alvy and Annie attempt to boil lobster or when Annie calls him over in the middle of the night to kill a spider after they have broken up. But also there are times when Alvy pushes Annie away; when she goes to California to record music with a stylish producer (Paul Simon), Alvy rejects that lifestyle for its lack of New York’s cosmopolitanism. Alvy (and Allen) thrives on walking down city sidewalks and talking—always in Allen’s stylized but oddly natural dialogue. His main characters talk to each other and their friends and their shrinks; they talk during racquetball, after sex, during a meal, and to the camera. Driven by dialogue captured in long takes, the film is as much a cross-section of Alvy’s life as is it an odyssey into Allen’s mind and heart. Through the film’s dialogue, the audience gathers a sense of Allen’s autobiographical strokes that, while embellished for the sake of comedy and romantic tragedy, paints a picture of memory and love and self-obsession that remains undeniable and universally true.

An even more intangible quality runs through Annie Hall and renders it infectious, namely Allen’s way of making his audience fall in love with Diane Keaton. The two had met during the stage production of Play It Again, Sam, after she earned a name for herself in the original Broadway production of Hair. Following a brief spell in which they dated and lived together, Keaton, born “Diane Hall” and serving as the direct influence for Annie, remained Allen’s acknowledged muse during his early films from Sleeper through Manhattan, and she even appeared intermittently in Allen’s films during his Mia Farrow period (1982-1992). Keaton’s singular and original personality conveys no end of charm and earned her an Oscar for the role. Indeed, her performance is less acting than simply Keaton being herself—a famously pleasant, self-deprecating persona that she suppresses in great dramatic appearances in The Godfather films, and embraces for Baby Boom (1987) and Manhattan Murder Mystery. A trendsetter in style, she even dressed herself in Annie’s signature Ralph Lauren trousers, vest and tie; costume designer Ruth Morley was told to leave Keaton’s attire to the actress, and her wardrobe has since become iconic. Keaton’s ability to remain amusing and subtly attractive in her idiosyncrasies is a characteristic that not even a writer of Allen’s skill could write, only write around and about.

How fitting then that Annie Hall’s theme—in spite of the miserably unfair world that Allen discusses at length—settles on love being the answer. What makes life worth living, Allen argues, are those brief moments of happiness that occur in our endless pursuit of love. In the end, after Alvy and Annie have broken up and moved on from one another, Alvy resolves that lasting relationships are almost impossible, and yet life without love is no life at all. He compares love to another old joke where a man tells his psychiatrist that his brother thinks he’s a chicken; the shrink tells him to turn the brother in, but the man refuses because he needs the eggs. “Well, I guess that’s pretty much how I feel about relationships. You know, they’re totally irrational and crazy and absurd and… but I guess we keep going through it because, uh, most of us need the eggs.” Allen’s assessment comes long after he and Keaton ended their own relationship, and yet his fondness for their time together carries on in this film, fuelling it. Annie Hall ends with Keaton singing “Seems Like Old Times” from Annie’s earlier lounge act, cut against a highlight reel of scenes from the film. Typically, such a montage would be a tacky way to remind the audience why they have enjoyed what they have seen, but here this device reinforces the film’s design as a collection of fond memories and regrets about love. If by the time we hear this song we have not already tapped into our own reminiscences, this sequence does the trick.

How fitting then that Annie Hall’s theme—in spite of the miserably unfair world that Allen discusses at length—settles on love being the answer. What makes life worth living, Allen argues, are those brief moments of happiness that occur in our endless pursuit of love. In the end, after Alvy and Annie have broken up and moved on from one another, Alvy resolves that lasting relationships are almost impossible, and yet life without love is no life at all. He compares love to another old joke where a man tells his psychiatrist that his brother thinks he’s a chicken; the shrink tells him to turn the brother in, but the man refuses because he needs the eggs. “Well, I guess that’s pretty much how I feel about relationships. You know, they’re totally irrational and crazy and absurd and… but I guess we keep going through it because, uh, most of us need the eggs.” Allen’s assessment comes long after he and Keaton ended their own relationship, and yet his fondness for their time together carries on in this film, fuelling it. Annie Hall ends with Keaton singing “Seems Like Old Times” from Annie’s earlier lounge act, cut against a highlight reel of scenes from the film. Typically, such a montage would be a tacky way to remind the audience why they have enjoyed what they have seen, but here this device reinforces the film’s design as a collection of fond memories and regrets about love. If by the time we hear this song we have not already tapped into our own reminiscences, this sequence does the trick.

With Annie Hall, Woody Allen created one of cinema’s greatest romantic comedies and signaled the arrival of a lasting, distinctive, artistic, yet accessible presence in American film. Presented in a loaded and allusive, almost free-association of scenes and episodes, the film holds together in an inexplicable and wondrous way during its stroll down memory lane, using a structure that many filmmakers have tried to imitate, but none—not even Allen himself—have replicated to such a moving degree. One finds themselves amazed by what a warmhearted, achingly funny film this is and how it all comes together so beautifully and tenderly, in spite of its expressive structure. Beyond its memorable dialogue and array of technical flourishes, the film advances Allen’s cinema at this point by offering characters and emotions of substance. His film reaches deeper than a series of undemanding, funny situations assembled to explore a comedian’s sense of humor, and announced Allen as a filmmaker of significance, one who would grow more complex and sophisticated in the coming years, and who would further establish himself as a romantic comedian, but also a vital auteur.

Bibliography:

Allen, Woody; Björkman, Stig. Woody Allen On Woody Allen. New York: Grove Press, 2005.

Blake, Richard A. Woody Allen: Profane and Sacred. University of Michigan: Scarecrow Press, 1995.

Fox, Julian. Woody: Movies from Manhattan. New York: Overlook Press, 1996.

Lax, Eric. Conversations with Woody Allen. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Lax, Eric. Woody Allen: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review