How to Make a Killing

By Brian Eggert |

In the United States, it’s impossible to escape the idea that wealth means success. It’s embedded into our culture, from Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous to a grotesque obsession with celebrity, ranging from various Real Housewives shows to the current POTUS. Even our heroes are billionaires, such as Batman’s alter ego, Bruce Wayne, who, when played by Ben Affleck, quips about his superpower: “I’m rich.” And doubtless, Charles Xavier must have paid hundreds of millions to install a secret training facility and jet hangar beneath the X-Mansion. When evaluating cinematic art, reactions from critics and moviegoers prove less important to the entertainment industry and public at large than box-office performance. A movie can receive a “Certified Fresh” badge on Rotten Tomatoes, but if it loses money, it becomes a “bomb.” Our culture doesn’t teach us to love art for art’s sake, and parents hope their children become well-paid doctors and lawyers, not underpaid teachers or struggling creatives. So, we seldom measure happiness by the number of friends we’ve made, people we’ve impacted, or what we’ve created, but rather, by the size of our bank account and how much stuff we acquire.

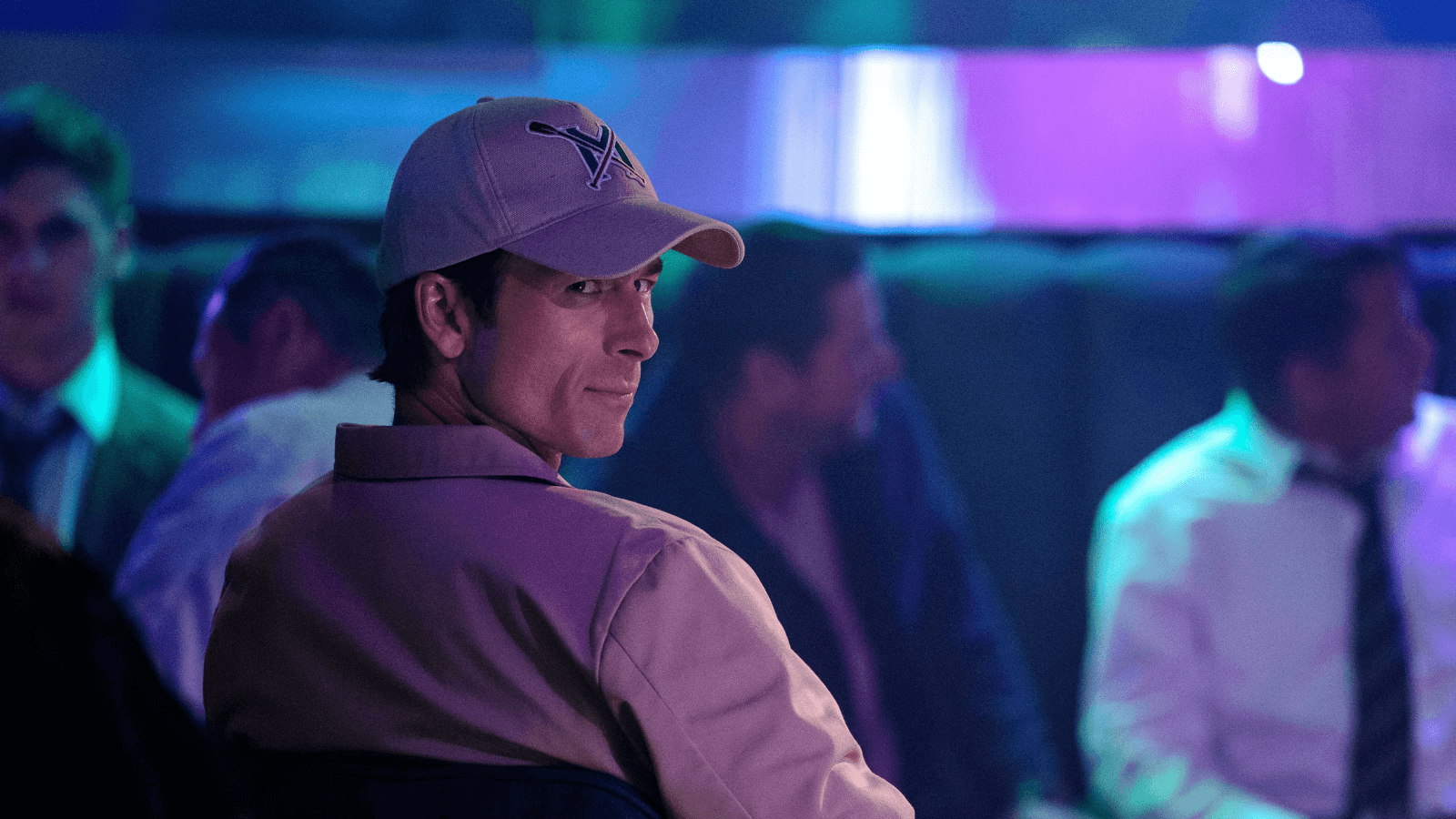

How to Make a Killing is about a disowned heir to a billion-dollar fortune who, like many of us, has been told from a young age to pursue “the right kind of life”—one of means. Glen Powell plays Beckett Redfellow, whose late mother (Nell Williams), on her deathbed, made him promise that he “won’t quit” until he gets what he deserves. He was conceived in a moment of adolescent passion, and his grandfather, Whitelaw (Ed Harris), demanded his mother get an abortion to save the Redfellow name from a scandal. When she refused, the patriarch cut her off. Forced to raise her son in Newark, New Jersey, without the family’s financial support, she taught Beckett about the finer things, preparing him for an inevitable return to the clan. But as years pass, and it becomes clear that his time will never come, he resolves to eliminate the seven members of the Redfellow family tree standing between him and billions.

Written and directed by John Patton Ford, How to Make a Killing feels light and airy with its fast-paced storytelling and slick filmmaking, yet its narrative structure is as bleak as a 1940s film noir. The filmmaker even borrows a noirish trope, with Beckett on death row, confessing, in near-constant narration, his crimes to the prison chaplain just hours before his scheduled execution. He recounts how, during a chance meeting with his well-to-do childhood sweetheart, Julia (Margaret Qualley), she asks about his inheritance and jokes, “Call me when you’ve killed them all.” This prompts him to conceive a sinister plan. He starts by targeting his finance-bro cousin (Raff Law), a wannabe Jordan Belfort, whom he easily disposes of on a boat. Only six more to go. Ford, no stranger to rooting for underdogs who operate outside of the law, also directed the excellent Emily the Criminal (2022), starring Aubrey Plaza in her best performance to date. In both, the filmmaker conveys an economic class hierarchy in which those at the bottom cannot win, while those at the top reap the benefits.

Ford based his screenplay on Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), a macabre Ealing Studios comedy that uses Roy Horniman’s 1907 novel Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal as a launching pad. Ford doesn’t follow the earlier texts too closely, nor does he replicate the movie’s iconic stunt in which the same actor (Alec Guinness) plays each of the eight family members in the protagonist’s crosshairs. However, the broad strokes remain intact, save for the necessity of a moralistic “crime doesn’t pay” finale. Quite the opposite. How to Make a Killing arrives amid increasing fervor against billionaires who, encouraged by the Trump administration, have sought to maintain their money and power by avoiding taxes, buying up media outlets, and quelling dissent. If ever a time in American history needed a splashy movie about the moral corruption of the so-called Epstein class, it’s now. And sure enough, the filmmaker never apologizes for his super-rich characters, who, besides their almost exclusively terrible behavior, he associates with some of cinema’s most disturbing members of their class.

Early in the proceedings, Beckett meets his uncle, Warren (Bill Camp), a kindly, remorseful man who regrets not reaching out to his nephew sooner. To make amends, Warren unexpectedly gives him a cushy Wall Street job. While getting close to another cousin, Noah (Zach Woods), a self-declared “white Basquiat,” he meets Noah’s girlfriend, Ruth (Jessica Henwick), and there’s instant chemistry. They both believe in the value of hard work over nepotism, and Ruth hopes to get out of fashion and teach literature to high-school students. Beckett’s eventual relationship with Ruth suggests that he may give up his pursuit and live a modest, happy life, except he soon embraces a Wall Street identity—complete with a swanky apartment and a stunning view. He begins dressing like Patrick Bateman from American Psycho (2002)—curiously, a role Powell already spoofed in Hit Man (2024). Yet, he continues murdering Redfellows and pursuing his inheritance.

One after another, Beckett murders relatives he’s never met before, each shallower than the last. Murder comes surprisingly easy to him, which, in terms of learning those skills, Ford doesn’t explore much. But that the antihero never loses sleep or seems overly worried about the morality of his actions should also tell you something about him. Then again, his victims are mostly deplorable. Among the most grotesque of them is the orange-tanned evangelical pastor (Topher Grace), who feigns godliness to launder money from his megachurch, all while defending his friendship with El Chapo. For much of the second act, How to Make a Killing delights in Beckett checking names off the family tree, following a recent trend in anti-capitalist movies that portray the rich as venal and deserving of comeuppance—see Ready or Not (2019), Parasite (2019), The Menu (2022), Triangle of Sadness (2022), Saltburn (2023), No Other Choice (2025), and the Knives Out series. All the while, he must fool the FBI and juggle his long-held affection for Julia, who has her own financial problems, and his seemingly grounded new relationship with Ruth, whom he plans to marry.

Whereas Ford’s work on Emily the Criminal felt gritty and reached for social realism, his aesthetic is punchier and more playful on his sophomore effort. Harrison Atkins’ editing crackles and maintains a brisk momentum, including comically timed cuts to funeral processions on the sprawling Redfellow estate in New York. There, the director stages a scene involving a gate and an envelope as a nod to Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), an extratextual allusion to the secret world of shady billionaires. Once Beckett begins to accumulate some wealth from his life in high finance, Todd Banhazl’s lensing transitions from a textured, slightly desaturated color palette to the polished, glossy look of Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987). Powell fits well into these surroundings and, with his chiseled jawline and smug, self-satisfied smile, appears to belong among the privileged ranks. That’s an intentional choice, wielding Powell’s sex appeal against the audience, even after he makes one self-destructive choice after another.

Ford’s concern lies not in seeing how his character will get away with it; instead, he’s more interested in whether Beckett will sell his soul in his undertaking. Why else would his screenplay—which appeared on the 2014 Black List of the best unproduced screenplays, under the title Rothchild, then later Huntington—spend most of the movie telling his story to a prison chaplain? But even more significant is Ruth, who remarks about dreaming small, and how “nobody teaches us how to do that.” Beckett ultimately chooses ambition and opulence over a smaller life of contentment or even happiness, and that’s what condemns him in the end, more than his murders, prison time, or the possibility of an execution. Pulled in opposite directions between two women, a money-grubbing femme fatale and a decent human being, his journey leaves us with the understanding that the happiest person in this story isn’t rich; it’s someone who feels fulfilled by her sense of self. How to Make a Killing is a timely morality tale, wrapped in a darkly funny and entertaining caper. And it’s another involving crime story directed with confidence by Ford, who delivers a fitting conclusion for Beckett Redfellow.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review