Emily the Criminal

By Brian Eggert |

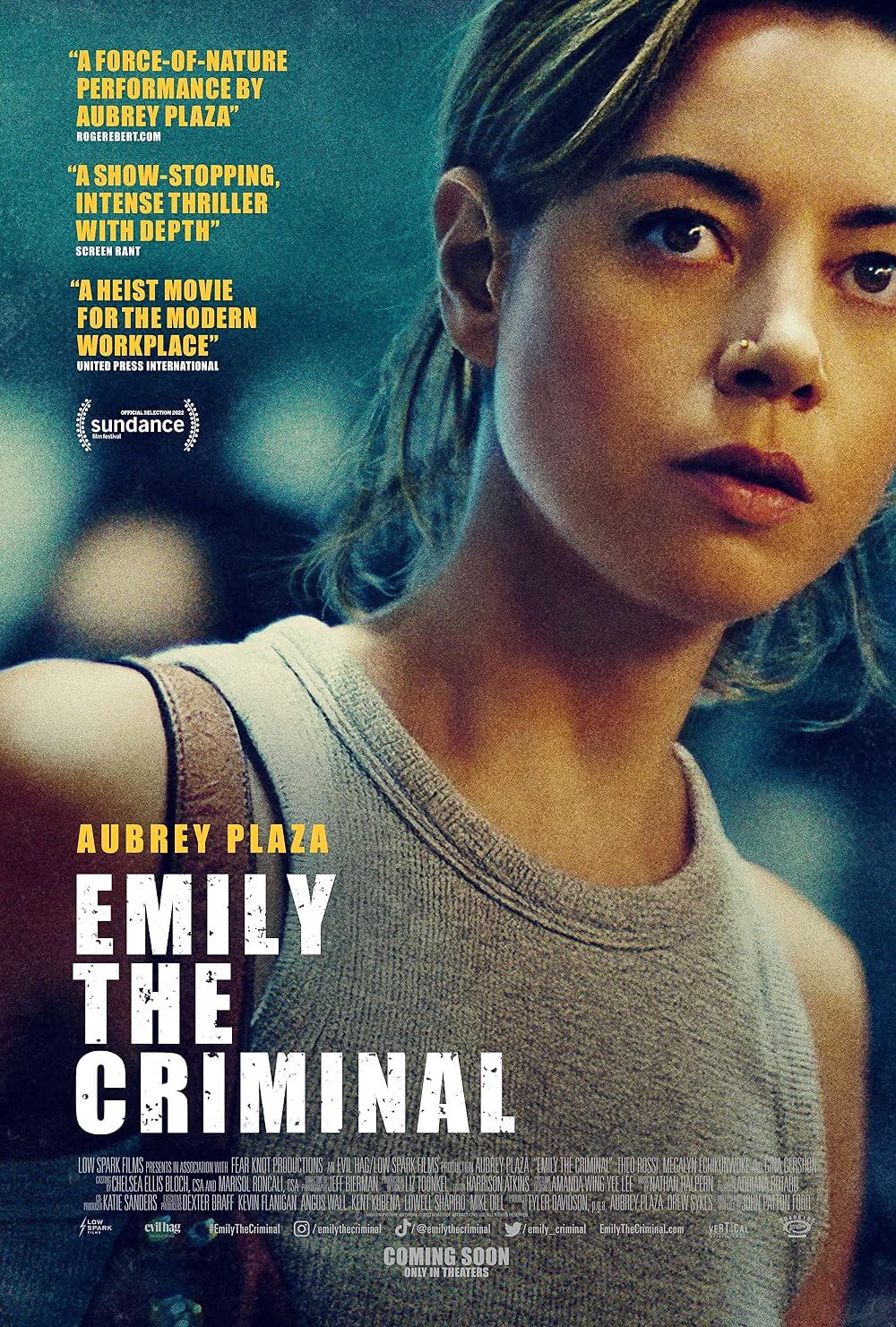

Aubrey Plaza launched a film and television career with her mischievous eyes. They whispered sardonic remarks to the camera in Parks and Rec, they barely conceal their default irony in her many collaborations with writer-director Jeff Baena (The Little Hours, et al.), and they share a knowing self-awareness with her audience. Plaza’s distinct eye-acting persona has left her typecast as sarcastic characters in a vast collection of frequently dark comedies. Through them all, she is a refreshing constant, even if her talent might seem dependent on a screen presence more than versatility—an observation less disparaging than it sounds, given that it’s an indefinable appeal that makes a movie star. But Plaza defies any preconceptions viewers may have about her capabilities as an actor in Emily the Criminal, a steely character study that answers a topical social problem with the crime genre. For the first time, Plaza disappears into her role, resulting in a career-best performance and one of 2022’s most captivating screen characters.

In this carefully calibrated debut feature from writer-director John Patton Ford, Plaza stars as the titular wannabe artist, crippled by $70,000 in student debt—and no, the Biden administration’s $10,000 forgiveness plan wouldn’t solve many of Emily’s problems. In the opening scene, she interviews for a position in the healthcare field, but she’s asked about a background check, which reveals a felony conviction for aggravated assault. Her circumstances prevent her from landing a white-collar job that would make her loans tenable, so she works in a kitchen and delivers catering orders to New York businesses. Achingly unsatisfied, Emily wants to draw and paint full-time, but for now, an artist’s unpredictable income won’t pay the bills. So when a coworker gives her a contact who will pay $200 for an hour of work as a “dummy shopper,” she shows up for the gig—as her desire for a quick payday is more vital than her anxiety over the cagey text communications with the entity behind this shady racket.

Ford, who received an MFA from the American Film Institute, directs somewhere between the confidence of Michael Mann and the humanity of Sidney Lumet. Emily the Criminal plays like the origin story of a Mann professional before the character has relentlessly compartmentalized inner passions or refused to allow any measure of concession. But Ford is capable of understanding the impossible predicament in which Emily finds herself. And yet Plaza, also serving as producer, doesn’t portray Emily as a victim of circumstance; after all, Emily’s behavior got her arrested for assault. Note the early nightclub scene that shows Emily isn’t above some reckless unwinding—including cocaine in a bathroom stall and drunken stumbling on a city street—with her childhood friend, Lucy (Megalyn Echikunwoke), who promises to arrange a job interview at her marketing company.

Indeed, beyond the system that preys on lower-to-middle-class young people who want a decent education, the film acknowledges that Emily is her own worst enemy. When she finally lands an interview with Lucy’s boss (Gina Gershon), the outcome is a distillation of how she refuses to compromise herself further than she already has. Unfortunately, Emily is driven by two forces that, when combined, collide with predatory systems of American capitalism: practicality and artistic inspiration. Emily has both. Most people in her situation would either sacrifice their artistic dreams to meet their financial obligations or be willing to suffer for their art (hence the term “starving artist”). But the two rarely exist in harmony. In Emily’s case, she wants the best of both worlds, and if a bit of dummy shopping gets her there, then so be it. Plaza conveys her internal negotiation of these stakes and considerations without over-articulating them in dialogue; her face tells us exactly what’s going through her head in restrained but readable expressions.

Indeed, beyond the system that preys on lower-to-middle-class young people who want a decent education, the film acknowledges that Emily is her own worst enemy. When she finally lands an interview with Lucy’s boss (Gina Gershon), the outcome is a distillation of how she refuses to compromise herself further than she already has. Unfortunately, Emily is driven by two forces that, when combined, collide with predatory systems of American capitalism: practicality and artistic inspiration. Emily has both. Most people in her situation would either sacrifice their artistic dreams to meet their financial obligations or be willing to suffer for their art (hence the term “starving artist”). But the two rarely exist in harmony. In Emily’s case, she wants the best of both worlds, and if a bit of dummy shopping gets her there, then so be it. Plaza conveys her internal negotiation of these stakes and considerations without over-articulating them in dialogue; her face tells us exactly what’s going through her head in restrained but readable expressions.

When Emily arrives for the gig in question, she finds herself in a grim warehouse with other desperate people. The group meets Youcef (Theo Rossi), a Lebanese immigrant who runs a credit card fraud operation with his intimidating cousin Khalil (Jonathan Avigdori). Youcef promises that what they are about to do will not bring harm to anyone—physically, at least—including themselves. The scam involves crafting credit cards with stolen numbers, buying big-ticket merchandise with the ersatz plastic, and then selling the merch on the black market. Desperate, Emily cozies up to Youcef, at once learning the trade to go independent and falling for him. They bond over their shared dreams of escaping their personal prisons. Eventually, Emily’s refusal to get swallowed up by debt leaves her with no choice but to go into the dummy shopping business for herself, but her pressing desire to escape her trap causes her to take dangerous risks. Still, her ingenuity appeals to Youcef; she even meets his mother in a tender scene—but that’s quickly broken up by the arrival of Khalil, who warns that Emily isn’t being careful. Going against Youcef’s instructions, she shopped from the same store twice in one week and put their whole operation at risk.

Ford builds tension out of what, for crime movie aficionados, is a small-stakes affair and what, for Emily, is the difference between freedom and a lifetime trapped by debt. Her troubled learning process, such as when a simple exchange in a public parking lot becomes a hair-raising confrontation for the diminutive young woman, is a nerve-racking development. Another, riskier purchase involves buying a car from two men, leaving Emily with a breathless eight-minute countdown before they discover the bank has denied her false cashier’s check. In each encounter, Jeff Bierman’s mostly handheld on-location shooting in natural light immerses the viewer in the situation, while Nathan Halpern’s score ratchets the suspense. It’s not the stuff of a lofty Hitchcockian thriller but a grounded, everyday urgency—the kind that keeps us up at night, thinking about our bills and responsibilities, hoping for a solution. Another person might buckle and resign themselves to the debt. Emily doesn’t—not even after two scuzzy thieves hold her at knifepoint, not even after she rebuffs a competitive internship that could lead to a legit career. Instead, she only sharpens, becomes more direct, and demonstrates that she’s capable of learning from her mistakes and becoming that Mann-esque professional.

The character, behind Plaza’s convincing New Jersey accent and hardened eyes, will not be intimidated. She has tasted financial independence and, regardless of her initial claims that “It’s only temporary,” refuses to allow anyone to get the better of her—and that means equipping herself with a taser and outsmarting the competition with an aggressive response in the final act. Plaza, born to Puerto Rican and Irish-English parents and trained as an improv comedian, proves she’s a committed actor in Emily the Criminal, capable of leaving her established persona behind and giving herself over to a character. Emily lives and breathes, and Ford’s assured direction keeps us on her side every step of the way, keeping his camera in Emily’s space, entrenched in her subjectivity. When Youcef’s mother tells her that God gives everyone a gift, the woman explains that it’s only a matter of discovering whether she’s “Emily the Artist” or “Emily the Teacher.” Emily finally realizes her calling (guess what it is), and it’s an inspired moment and a grim commentary on the necessity for criminalized self-reliance in America today.

The character, behind Plaza’s convincing New Jersey accent and hardened eyes, will not be intimidated. She has tasted financial independence and, regardless of her initial claims that “It’s only temporary,” refuses to allow anyone to get the better of her—and that means equipping herself with a taser and outsmarting the competition with an aggressive response in the final act. Plaza, born to Puerto Rican and Irish-English parents and trained as an improv comedian, proves she’s a committed actor in Emily the Criminal, capable of leaving her established persona behind and giving herself over to a character. Emily lives and breathes, and Ford’s assured direction keeps us on her side every step of the way, keeping his camera in Emily’s space, entrenched in her subjectivity. When Youcef’s mother tells her that God gives everyone a gift, the woman explains that it’s only a matter of discovering whether she’s “Emily the Artist” or “Emily the Teacher.” Emily finally realizes her calling (guess what it is), and it’s an inspired moment and a grim commentary on the necessity for criminalized self-reliance in America today.

Moralistic viewers may take issue with Emily the Criminal’s conclusion and perhaps yearn for something more attuned to the Production Code, complete with comeuppance for the wrongdoer protagonist. But in a world where morality aspires to be black and white within a grayscale system of economic exploitation and maximized profits, absolutes are a luxury. Emily is a character who recognizes this and sees the situation for the opportunity it affords. When Yousef asks her about her choices—“You can’t make money any other way?”—she can only respond by asking him the same question. It’s at once a response to a capitalistic problem and an underdog story in how she defies the system that both preyed upon and disregarded her. As an anti-hero, or possibly a just-plain hero, Emily is fascinating, direct, unwavering, and human. Plaza brings her to life in a terrific performance.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review