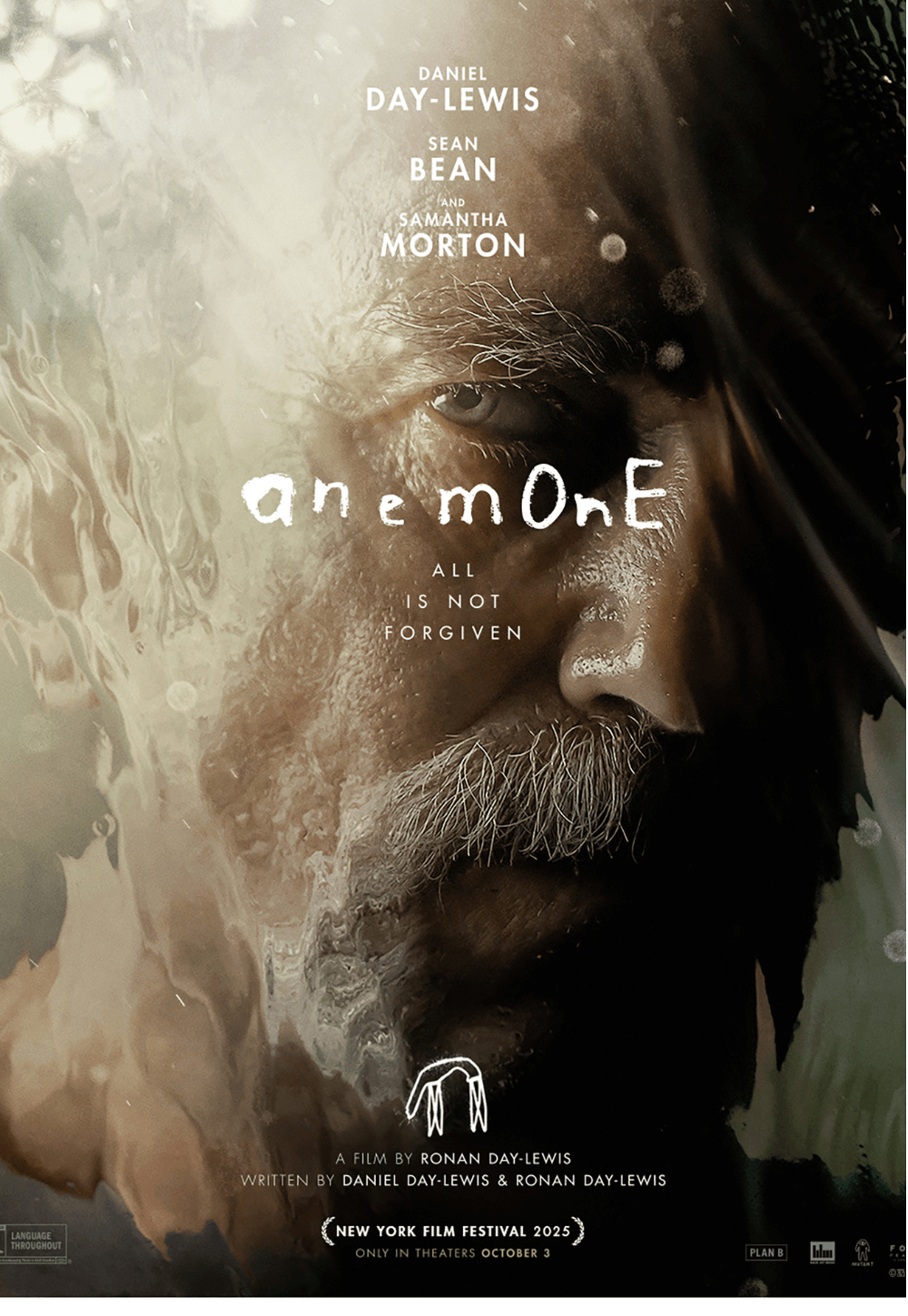

Anemone

By Brian Eggert |

Anemone reaches for profundity yet achieves only a thin exploration of generational trauma, albeit presented with gorgeous filmmaking and stunning images of lush green landscapes in Northern Ireland. The film marks the directorial debut of Ronan Day-Lewis, who convinced his father, Daniel, to come out of an eight-year retirement following his last appearance in Paul Thomas Anderson’s sublime Phantom Thread (2017). Father and son collaborated on the screenplay, telling a story propelled by a few characters, minimal dialogue, and pensive scenes of contemplation. At once mesmerizing and frustratingly slight, the drama considers the long-tailed consequences of The Troubles. However, Anemone’s approach resists the usual realism that accompanies this subject matter in favor of an entrenched, slow-cinema aesthetic, accentuated by the late addition of magical realism that is bound to baffle some viewers. Even so, its terrific performances and promising first-time director make this a fascinating and admirable picture, though uneven.

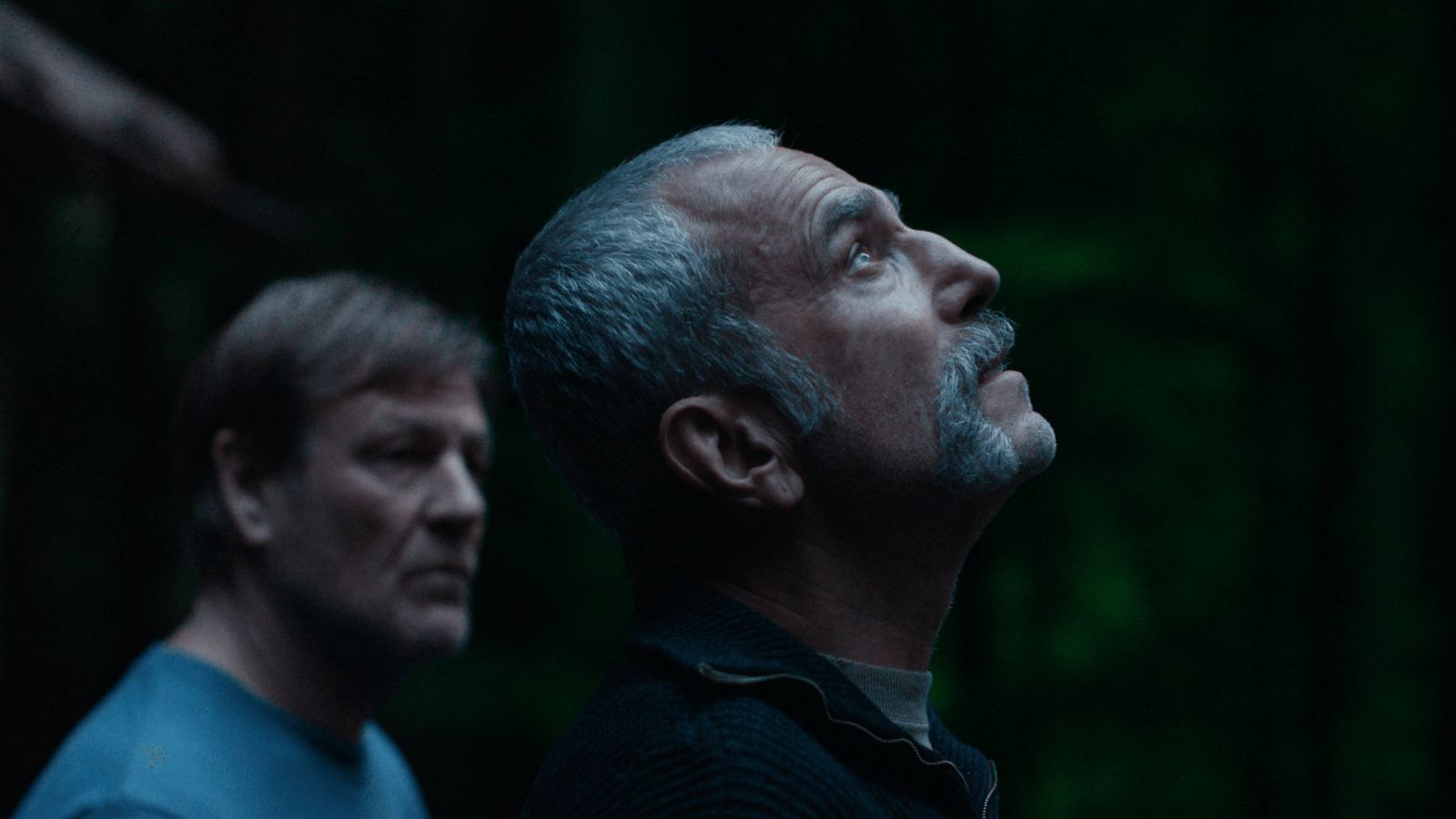

From the first images, the director and his cinematographer, Ben Fordesman (Saint Maud, 2019), favor bold, contemplative shots of natural beauty over narrative thrust. Although the title refers to a perennial flower, one cannot help but think of a sea anemone as well. The younger Day-Lewis captures grassy fields and the treetops from a bird’s-eye view, both of which move in the wind like underwater tentacles. Deep inside a forest, like a clownfish who swims among the anemones for protection, lives Ray (the elder Day-Lewis). He’s a self-described “deranged fugitive” whose wiry physique, silver hair, and handlebar mustache capture the character’s self-imposed spartan lifestyle. Reticent and often downright mean, Ray disappeared 20 years ago and has been living alone in the woods ever since. After fighting for the British military against the IRA, Ray deserted his former life for isolation. The question of why becomes a mystery that the viewer must gradually, patiently learn as the story unfolds over two hours.

Early on, Ray’s hermetic world bursts with the unannounced arrival of his brother, Jem (Sean Bean). After two decades, Ray’s wordless greeting consists of tea and sharp gestures, accented by Day-Lewis’ signature severity. Initially, there’s no warmth or tenderness between the siblings, only a days-long hesitance to discuss their past—from an unloving father who said little, to Ray’s experience with sexual abuse by a priest. Not surprisingly, Ray has no room for faith in his spare, cynical, angry mind, while Jem remains devout, complete with prayers at mealtime and a tattoo that reads “Only God Can Judge Me.” The reason for the visit: Jem delivers a letter from Nessa (Samantha Morton), the mother of Ray’s son, Brian (Samuel Bottomley), whom Ray has never met. A young soldier, Brian has gotten into trouble with the British military, as evidenced by his bloody knuckles. Nessa hopes Jem and her letter will convince Ray to return home and help his son.

The screenplay might feel like a chamber drama if not for the remarkable, sweeping visuals. Much of the story consists of lengthy monologues, almost entirely performed by the two-time Oscar winner. One memorably grotesque passage involves Ray recounting an elaborate (possibly made-up) revenge he carried out on his abuser, and another finds him confessing what caused his exile. Between these entrenched speeches, the director creates contemplative shots of the brothers hiking through the verdant forest, dancing like punk rockers, or wrestling like children. Through it all, Bean’s role registers as passive. He doesn’t show up to pressure his brother into returning; rather, he waits and listens, his presence gradually eating away at Ray’s resolve. Their quiet moments together are interrupted by brief scenes where Nessa appeals to Brian, attempting to defend his absent father. And even though these scenes feel weighted by psychological trauma and abandonment, the script never manages to give the material much depth.

A dream-memory Ray experiences early in the film leads to several haunting, uncanny, fantastical moments later in the film, shifting the mood from a stark human drama to existential surrealism. For instance, Ray sees a glowing, translucent thing that surely represents Brian—although the question of why it looks like the Great Forest Spirit from Princess Mononoke (1997) remains. A climactic scene with a hailstorm recalls the frog-rain in Magnolia (1999), as fist-size ice pummels everything and serves as a great equalizer that neutralizes Ray’s apprehensions about returning home. Elsewhere, the director and his editor, Nathan Nugent, include near-subliminal flashes of blood, milk, and viscera to evoke The Troubles. Unfortunately, the most dramatically pronounced sequences are accompanied by Bobby Krlic’s distracting score, featuring deafening, metallic guitar riffs that sound like they’re trying to strum life into the otherwise quiet and intentionally paced proceedings.

By the move toward reconciliation in the conclusion, Anemone entrances the viewer with its beauty and intense performances—particularly from the magnetic Day-Lewis, whose screen presence has lost none of its spellbinding complexity. Bean and Morton also make significant contributions to the story’s emotional force. But the measured narrative gait hardly matches the director’s loaded visual and tonal techniques, and I noticed several walkouts at my screening, presumably due to sheer boredom. It’s that kind of film, one that some will find engrossing, and some will find a chore to finish. For its gorgeous imagery and admirable performances, Anemone introduces a promising new director. Apart from these qualities, the film’s themes of fathers and sons, old wounds, and prolonged guilt never quite resonate with the same ferocity that actors of this caliber deserve.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review