The Definitives

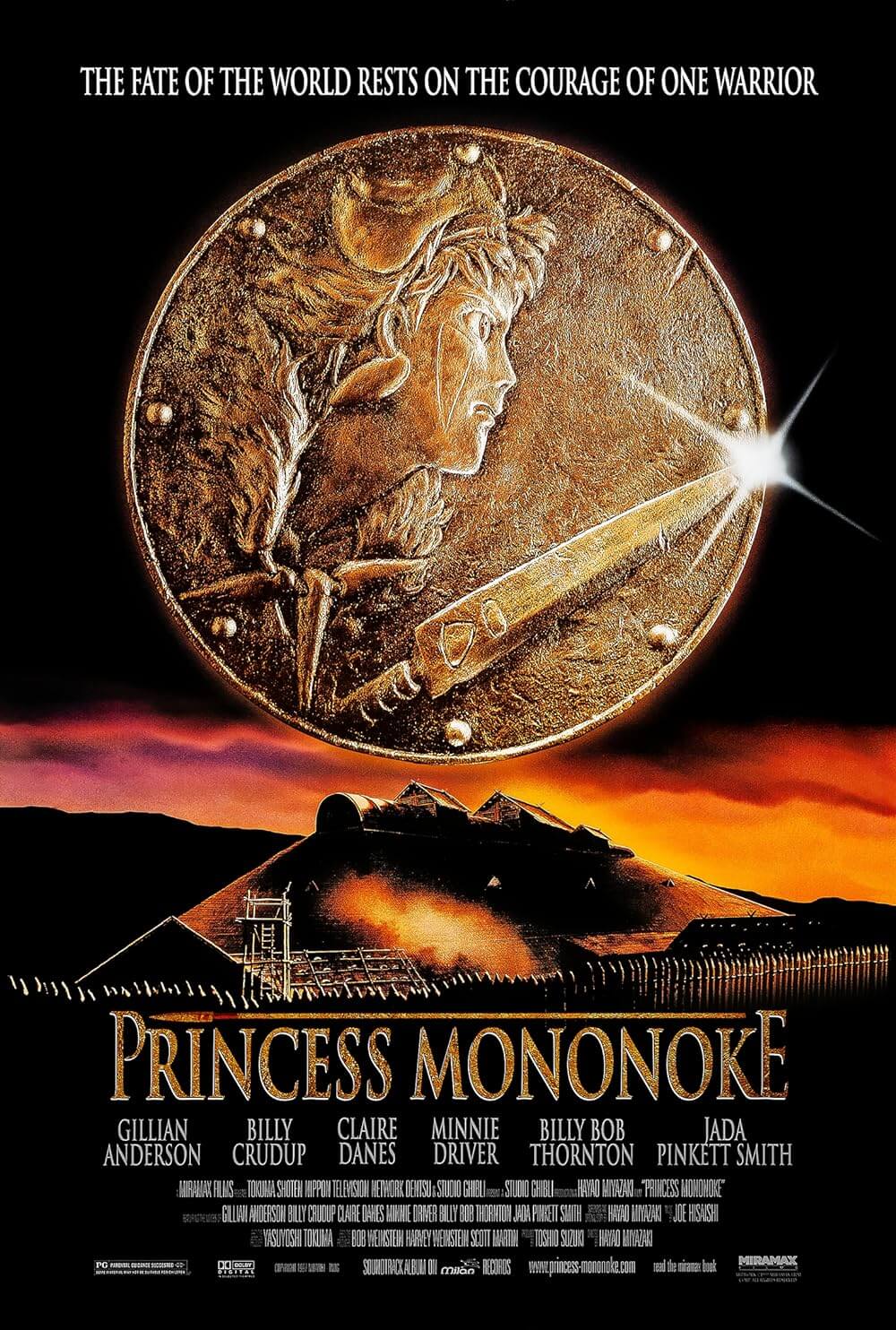

Princess Mononoke

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Certain elements of storytelling are left to chance in live-action filmmaking. An actor improvises a line; natural light shifts to change the meaning of a scene; the cameraman embraces a moment of spontaneity. Where live-action seems to be about achieving some semblance of order out of controlled chaos, animation requires more invention. The animated medium involves building detailed worlds, designing every component of the story from imagination. Characters, settings, and their presentation come together not through a random set of artistic flourishes, but rather through strictly controlled collaborative artistries driving toward the same purpose. Hayao Miyazaki wrote that he defines animation as “Whatever I want to create.” His meaning resides in the realm of possibility, as no limit exists for animation. Comic books, television, and even live-action filmmaking reduce storytelling possibility down to the limits of the chosen medium, contingent on requisite budgetary concerns and achievable formal panorama. Animation sets no boundaries to storytelling. Miyazaki’s 1997 film Princess Mononoke (Mononoke-hime) demonstrates this truism beautifully and completely. In terms of narrative and substance, his film is such a sprawling, perceptive wonder. The story could not be told through another medium, nor could another director wield its vast scope. Inside a grand adventure, Miyazaki communicates humanist ideas and visual scenery beyond compare, with all the grace and composure of a true artist-craftsman.

Along with Isao Takahata, Miyazaki co-founded Tokyo’s premier animation house, Studio Ghibli. The company manages production on a number of overlapping projects, but Miyazaki remains the leading director at Ghibli, existing as the only author in the entire field of animation, and certainly the only auteur. On every film, Miyazaki oversees an entire team of animators dedicated to his vision. Working from his own script and story, he also contributed to nearly every frame used in Princess Mononoke (approximately 144,000), carefully monitoring the efforts of his crew, while hand-drawing thousands of images himself (in the order of 80,000). His artistic fingerprints adorn nearly every illustration that appears onscreen. This has long been his practice, earning him the reputation of being obsessed and a workaholic. When released in Japan in 1997, Princess Mononoke surprised Studio Ghibli with its success. The production actively toiled from 1995 to 1997 and eventually cost around $20 million (or ¥2.5 billion) to complete. When it was released, 12 million Japanese, roughly one-tenth of Japan’s population, saw the film. It held a brief box-office record, beating out Steven Spielberg’s E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial as the all-time top-grossing film in Japan, only to be defeated that same year by James Cameron’s Titanic. Miyazaki later reclaimed his number-one earning spot when Spirited Away was released in 2001. Princess Mononoke began the reign of Miyazaki at the Japanese box-office; though his earlier films did admirably, they often relied on rental and toy sales to achieve a profit. But after his 1997 picture, Miyazaki remained a blockbuster animator.

How strange that this is so, given the weighty subject matter of the film. The setting is Japan’s Muromachi Period (1336-1573), wherein Zen Buddhism spread, Christian Jesuits and Chinese satraps penetrated the landscape, and new ideas sprung about from all directions. Presented in the form of a traditional jidaigeki, a Japanese period piece, Miyazaki’s film leaves nobles and samurai on the sidelines. Instead, he utilizes the era as an allegory for disorder in the information and digital age, for the ever unbalanced relationship between Nature and humanity. The film’s epoch was the first time in Japan’s history that its people tried to tame Nature versus worship it, raping the land for its treasures and using them to further the superiority of humankind. And given how “progress” played out in humanity’s favor, there can be no happy endings from this story, at least not for Nature. But then, this is not a tale of white heroes and black villains. The entire picture takes place in a gray area where only Miyazaki’s profound humanism prevails. With epic ideals like Nature and love and understanding at the heart of an adventure story, the film orbits (as opposed to confronts) the problem of humanity as it relates to the ecosystem.

How strange that this is so, given the weighty subject matter of the film. The setting is Japan’s Muromachi Period (1336-1573), wherein Zen Buddhism spread, Christian Jesuits and Chinese satraps penetrated the landscape, and new ideas sprung about from all directions. Presented in the form of a traditional jidaigeki, a Japanese period piece, Miyazaki’s film leaves nobles and samurai on the sidelines. Instead, he utilizes the era as an allegory for disorder in the information and digital age, for the ever unbalanced relationship between Nature and humanity. The film’s epoch was the first time in Japan’s history that its people tried to tame Nature versus worship it, raping the land for its treasures and using them to further the superiority of humankind. And given how “progress” played out in humanity’s favor, there can be no happy endings from this story, at least not for Nature. But then, this is not a tale of white heroes and black villains. The entire picture takes place in a gray area where only Miyazaki’s profound humanism prevails. With epic ideals like Nature and love and understanding at the heart of an adventure story, the film orbits (as opposed to confronts) the problem of humanity as it relates to the ecosystem.

Set in a time when gods and demons filled the forests, the film’s ancient landscape breeds an atmosphere of mystique and magic, of history and fantasy, where Nature still retains a significant, if not dominant control over the world. The landscape is non-industrialized and largely vacant of agricultural influence; human society has not yet been dominated by authoritarians. Nature exists in a pure form, wild forests cover the hills, and the human presence has not yet flooded and ultimately overflowed as of yet. To capture the visual style appropriate to such surroundings, Miyazaki’s artists researched their topic in the Shirakami Mountains, where thousand-year-old trees with massive, fantastical trunks still stand. Animals talk in the film, but not like Disney characters—they are not anthropomorphized, nor do they break into song to express themselves. The animals are savage creatures that speak of tearing apart human flesh, and they inhabit an expansive Ancient Forest filled with ghostlike “Kodama”, or forest spirits, their heads winding and rattling in curiosity and delight.

Since Miyazaki is a pacifist, the protagonist of this story is a nobleman caught between warring parties, one representative of Nature, the other of Industry. The hero’s name is Ashitaka, a warrior from a distant village riding on the back of an elusive red elk. In the first scenes, a forest demon emerges from the woods near Ashitaka’s village, writhing with a black wormlike contamination. Protecting his people as they run to safety, he draws the monster’s attention with his bow. The demon attacks, grasping Ashitaka’s arm, and the hero returns the attack by dropping the beast with an arrow. As the demon dies, its outer layer of black disease dissolves to reveal a giant boar underneath. The old wise woman of the village informs everyone that the boar was a forest god corrupted by an iron bullet, twisted into a demon when it was shot. After being touched by the demon’s disease, Ashitaka’s scarred arm represents an enduring symbol of Industry’s threat to the village. It will eventually devour him body and soul, just as Industry will eventually spread to wipe out small villages like Ashitaka’s. For now, to protect the village, he must leave everything he knows behind and journey to the Ancient Forest, where the Great Forest Spirit, named Tatarugami, can possibly heal him.

On the road to faraway lands, Ashitaka feels the demon’s influence growing deep in his arm. It seems to apply deadly violence onto those who attack him, a force Ashitaka must keep in check. When he comes upon a clan of samurai slaughtering a farming community, his arm takes over in a rage; the result is numerous samurai relieved of their head or arms by Ashitaka’s bow. His curse derives its influence from the iron, the driving force of Industry that is both powerful and corruptive. And so, Ashitaka gains strength from the curse, but it also destroys his purity through its power. In a market village, Ashitaka meets Jigo, a self-proclaimed monk searching for a permanent solution to his poverty troubles. The Emperor of Japan has placed a bounty on the head of the Forest Spirit Tatarugami to protect iron production, and whoever brings the head to him will be showered with riches. Jigo schemes to find Tatarugami, kill it, and remove its head. Meanwhile, Ashitaka approaches the iron town Tataraba, a village of ex-prostitute iron workers, leper gunsmiths, and a usual smattering of men all lead by a futurist leader, Lady Eboshi, who plans to lay to waste the forest and its various animal gods, and ultimately kill Tatarugami. The Tataraba feed from the Ancient Forest, flattening the woodlands to further profit from iron sales, though they too need the forest to survive. To be sure, Miyazaki has intentionally made the clan and spirit’s names similar, as they are fundamentally connected.

On the road to faraway lands, Ashitaka feels the demon’s influence growing deep in his arm. It seems to apply deadly violence onto those who attack him, a force Ashitaka must keep in check. When he comes upon a clan of samurai slaughtering a farming community, his arm takes over in a rage; the result is numerous samurai relieved of their head or arms by Ashitaka’s bow. His curse derives its influence from the iron, the driving force of Industry that is both powerful and corruptive. And so, Ashitaka gains strength from the curse, but it also destroys his purity through its power. In a market village, Ashitaka meets Jigo, a self-proclaimed monk searching for a permanent solution to his poverty troubles. The Emperor of Japan has placed a bounty on the head of the Forest Spirit Tatarugami to protect iron production, and whoever brings the head to him will be showered with riches. Jigo schemes to find Tatarugami, kill it, and remove its head. Meanwhile, Ashitaka approaches the iron town Tataraba, a village of ex-prostitute iron workers, leper gunsmiths, and a usual smattering of men all lead by a futurist leader, Lady Eboshi, who plans to lay to waste the forest and its various animal gods, and ultimately kill Tatarugami. The Tataraba feed from the Ancient Forest, flattening the woodlands to further profit from iron sales, though they too need the forest to survive. To be sure, Miyazaki has intentionally made the clan and spirit’s names similar, as they are fundamentally connected.

Outside of Tataraba, circling the structure, Princess Mononoke leads her enormous wolf brethren with plans to kill the developing town leader, Lady Eboshi, the cause of deforestation to her home. Born from humans and raised in the Ancient Forest by the wolf-god Moro, the Princess has a feral heart and represents the human epitome of Nature, whereas Lady Eboshi represents Industry. The two are jealously devoted to their objectives and determined to kill one another. Ashitaka, fascinated with the Princess, tries to stop both she from attacking Tataraba and the humans from killing Tatarugami, whereas both parties accuse him of helping their enemy. Ashitaka refuses to take sides, however; he has no angle other than peaceful coexistence. While searching for Tatarugami to heal his cursed arm, Ashitaka’s task becomes achieving balance between rampantly fading Nature and violently growing Industry, both which gather forces to collide in a massive battle.

Good and evil remain indefinite throughout the plot of Princess Mononoke, as the preservation of Nature is essential, but the community advancements of Lady Eboshi’s clan are also admirable. The two idealisms smash together, and only Ashitaka can see that symmetry and understanding between the two will resolve their conflict. Ambiguous definitions for protagonists and antagonists central to the narrative are signature Miyazaki tropes, prevalent in his work since his second feature, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. His villains are usually sympathetic in some way, to demonstrate how political climates always contain uncertainty, and how only in the most thinly described fiction do extremes of right and wrong exist. In this way, despite his often fantastical settings, Miyazaki films prove more realistic than your average adventure story.

To find some semblance of equilibrium, Ashitaka must penetrate the mutually inflexible, self-contained worlds of Princess Mononoke and Lady Eboshi. Both are worlds enclosed within bubbles; the film acknowledges that once the bubbles meet in their violent way, they burst, resulting in chaos and war. Ashitaka is there to ease them together, so that the bubbles might merge so the two can subsist individually, yet in harmony. The film slowly reveals itself to be about breaking barriers and realizing that coexistence is possible, necessary, but not probable. Nature and Industry are forced to acknowledge the permanence of one another, but the process is not pleasant. Humanity, a destructive juggernaut, always incites the shift toward change, and if Nature resists, it will be conquered altogether. Better to coexist, Miyazaki would argue. However, humanity must take care to allow Nature its space, as it provides no end of sustenance if properly cultivated.

Miyazaki insists that madness drives blind faith in Industry’s technological advancements, and that the idea of “development” does not infer improvement. He resists the belief that technology solves everything, as if Nature somehow got it all wrong. But he also recognizes the importance of non-intrusive advancements, of technology that benefits humankind without destroying something else. Faith in technology over Nature is the chief destructive force in the film, which is Lady Eboshi’s lesson. Why else would a simple iron bullet drive a forest god to madness? But to resist advancement altogether in the name of Nature prevents growth from occurring, which also has its dangers. For Miyazaki, the impossible balance between Nature and Industry stands as the ideal, the unachievable ambition that should drive humanity. Perhaps the director’s peaceful ending to Princess Mononoke, when the opposing sides achieve this balance through their conflict, is what makes the film a fantasy.

What Miyazaki preaches onscreen he practices offscreen as well. The director does not resist technology as a rule, or he never would have employed computer-generated animation for the first time to support his hand-drawn animation. Computer animation, which under his employ disappears into the hand-drawn animation, brings connectivity between frames and does not distance the mediums through stylistic divergence. The effect transforms a lush living forest into a skeletal jungle in a swift wave, captures the movements of Tatarugami’s globulous form and those of forest demons, and miraculously brings flora back from death in the final scenes. In true narrative reflectivity, hand-drawn animation signifies the natural state of the medium, or Nature, and computer animation embodies the advancements, or Industry. As in the climax of the film’s story, the two come together in a seamless marriage, whereas Miyazaki’s later films, most notably Howl’s Moving Castle, would not be so flawless. No other filmmaker has implemented computer animation into traditional animation so effortlessly and invisibly as in Princess Mononoke.

In a transitional scene, the frame takes a tranquil moment to quietly consider a rock surrounded by grassy vegetation. Rain begins to patter, and then swells to a downpour, altering the color scheme of the image from a shining landscape to a dampened shade, suggesting the oncoming storm of battle. Reminiscent of an Akira Kurosawa-esque detail, this minimalist and seemingly inconsequential ornamentation, augmented by computer animation or not, serves as a testament to Miyazaki’s senses both as an animator and storyteller. The art design on the film is the director’s most mature looking work, avoiding cartoonish stylization of either character or narrative. In terms of classical staging more akin to motion pictures than anime, the aforesaid similarity to Kurosawa is undeniably true when Princess Mononoke is compared to vivid color epics like Kagemusha and Ran. The clarity of animation and purpose behind it emphasize each glorious detail, making everything within the full frame richly within reach, and strangely more real as a result of the composed animation.

In a transitional scene, the frame takes a tranquil moment to quietly consider a rock surrounded by grassy vegetation. Rain begins to patter, and then swells to a downpour, altering the color scheme of the image from a shining landscape to a dampened shade, suggesting the oncoming storm of battle. Reminiscent of an Akira Kurosawa-esque detail, this minimalist and seemingly inconsequential ornamentation, augmented by computer animation or not, serves as a testament to Miyazaki’s senses both as an animator and storyteller. The art design on the film is the director’s most mature looking work, avoiding cartoonish stylization of either character or narrative. In terms of classical staging more akin to motion pictures than anime, the aforesaid similarity to Kurosawa is undeniably true when Princess Mononoke is compared to vivid color epics like Kagemusha and Ran. The clarity of animation and purpose behind it emphasize each glorious detail, making everything within the full frame richly within reach, and strangely more real as a result of the composed animation.

But where an audience could lose itself in appreciating the raw animation—the eerie yet gorgeous presence of the Ancient Forest, the scope of the battle scenes, the effortless character design—Miyazaki himself values themes over technique. As early as the 1970s, Miyazaki had sketched out a vague notion of the final film and its implications, the conflicts between humans and Nature, and the environmentalist undercurrents that remain so important to the director to this day, as evident in his 2009 release Ponyo. Throughout his body of work, Miyazaki has exhibited his disdain of the modern world, a place where video games and television distance humanity from Nature. By telling stories like Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki seeks to rejoin humanity and Nature by infiltrating cinema and infusing it with themes that articulate the need for balance between the two. Above all else, Princess Mononoke is a film that stands against intolerance in all its forms, political or social, and demands coexistence and understanding from its audience. How bold for what is, in its most simplified definition, a cartoon. Wielding an unparalleled concentration of author’s insight and artistic control, Hayao Miyazaki has transcended the limitations of anime, cartoons, and the modern designation of animated feature. Through Miyazaki’s singularity as a storyteller and artist, his brand of animation, the high art of his medium or any other form of cinema, he offers an arena where the most unlikely of stories can be told, and they often are.

Bibliography:

Cavallaro, Dani. The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki. Mcfarland: 2006.

McCarthy, Helen. Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation. Stone Bridge Press: 1999.

Miyazaki, Hayao. Starting Point: 1979-1996. VIZ Media. 2009.

Odell, Colin & Michelle Le Blanc. Studio Ghibli: The Films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, Oldcastle Books: 2009.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review