Caught Stealing

By Brian Eggert |

One surprising thing about Darren Aronofsky’s Caught Stealing is that it’s a fun little crime picture that eschews (most of) the heavy-handed symbolism and ultra-serious thematic concerns usually found in the director’s work. Here’s a movie featuring cat reaction shots and an animated end-credits sequence—not the sort of playfulness the viewer expects from Aronofsky. If you took his name off and slapped on Guy Ritchie’s instead, it might make more sense given their respective filmographies. However, it’s a refreshing change of pace for a filmmaker whose output includes psychodramas such as Black Swan (2010) and mother! (2017), tormented portraits of humanity in The Wrestler (2008) and The Whale (2022), and out-there fantasies with The Fountain (2006) and Noah (2014). Another surprising thing about Caught Stealing is that, even though this cat-centric story takes place in 1998, the filmmaker opted not to use Jane’s Addiction’s 1990 hit “Been Caught Stealing” on the soundtrack and replace the song’s dog barking with cat meows. But you can’t have everything.

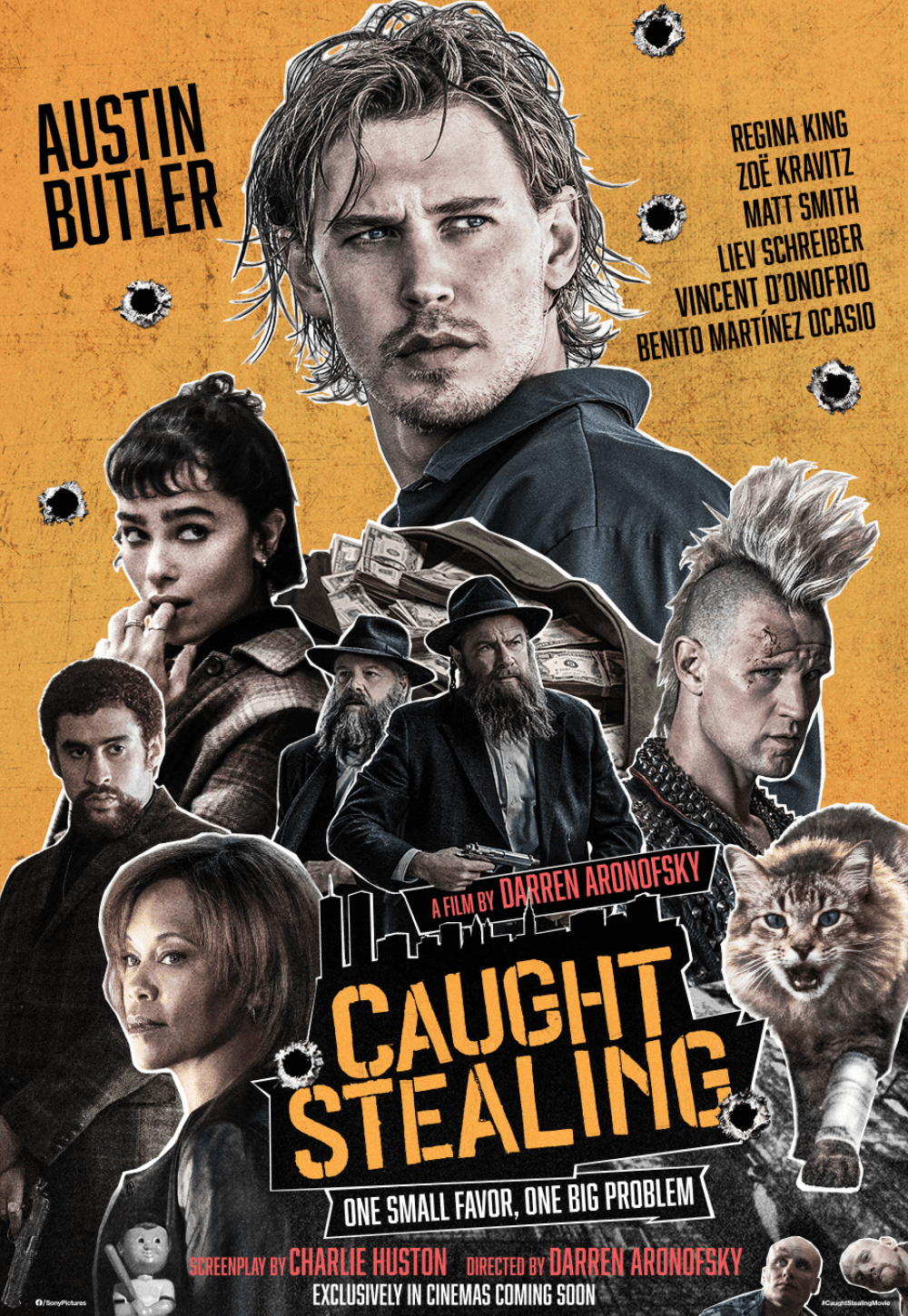

Written by Charlie Huston and based on his 2004 book, Caught Stealing has the dynamism of other scrappy crime stories of this ilk. Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985) and a movie it inspired, Good Time (2017) by Josh and Bennie Safdie, come to mind, along with Ritchie’s many Tarantino-esque efforts from Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) to RocknRolla (2008). Aronofsky’s movie is a fast-paced and seedy tale about various shady characters—gangsters, small-time crooks, corrupt cops, and the other usual suspects—double-crossing and killing each other for a substantial amount of money. A star-studded ensemble plays the rogues’ gallery of scoundrels and miscreants, each in small enough roles to deliver a couple of memorable scenes before exiting the story, one way or another. And Aronofsky allows himself, perhaps for the first time in his career, to instill an infectious sense of zippy entertainment value into the proceedings.

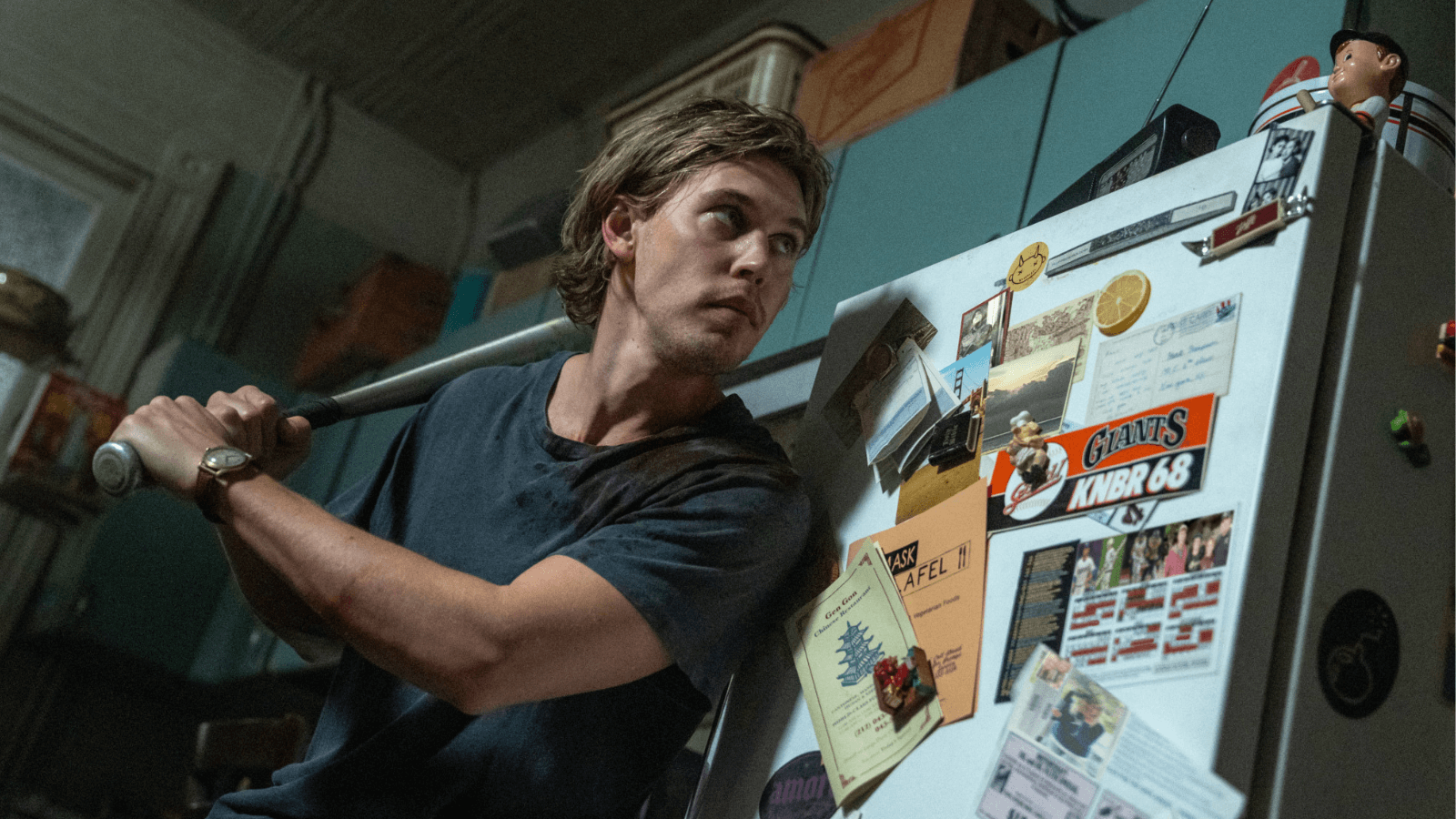

Caught Stealing might seem gritty and brutal in another filmmaker’s hands, but given Aronofsky’s track record of uncompromising, even punishing material, it registers as lighthearted escapism by comparison. Austin Butler stars as Hank, a California native who once had a promising career in professional baseball lined up before an accident shattered his knee, derailing his future. Hank now lives in a crummy apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and makes a modest living tending bar (Griffin Dunne plays his boss, a nod to After Hours). Besides some heavy drinking, daily calls back home to his mother (a San Francisco Giants superfan) and regular visits from his getting-serious girlfriend Yvonne (Zoë Kravitz) keep him from dwelling on his situation. Though, nightmares of the accident remind him of his mistakes. The plot kicks into gear when Hank’s punk-rocker neighbor, Russ (Matt Smith), flies to London to visit his ailing father, entrusting his cat, Bud, to Hank.

Given the title’s baseball metaphor—unsubtly underlined by the opening stealing-home sequence—it doesn’t take long for Hank to realize he must maneuver between various threats, like he’s in a rundown between two bases. The trouble begins when two Russian gangsters come looking for Russ only to find Hank, whom they beat up so badly that he’s hospitalized and has to have one of his kidneys removed. Refreshingly, Hank isn’t an impervious hero but a sensitive guy who doesn’t want trouble. When he realizes some bad people are looking for Russ, he calls Detective Roman (Regina King), who’s leading the investigation. She warns Hank about a club owner named Colorado (Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio) and two Hasidic gangsters (Vincent D’Onofrio and Liev Schreiber), whom she describes as “scary monsters.” The latter two, sadistic as they are, introduce Hank to their Bubbe (Carol Kane) and seem to have a moral code. “Sad world. Broken world,” they reflect. The lot of them are after something Russ has hidden, and when Hank finds it, he must scramble to survive.

The movie takes place at a transitional moment in New York City, caught between the grimy streets of previous decades and Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s push for stringent laws and gentrification. Although Caught Stealing looks like a scrappy, street-level crime picture, the amount of CGI required to portray the Big Apple in 1998 is probably more than it seems. Not that the viewer notices, in part because Aronofsky, cinematographer Matthew Libatique (fresh off Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest), and editor Andrew Weisblum keep the proceedings moving and visually dynamic, with a grainy edge to the footage. The ’90s atmosphere receives help from a few pop-culture hallmarks (Smash Mouth, Jerry Springer, etc.), and Aronofsky’s penchant for nastiness remains present throughout (vomit, clogged toilets, torn stitches, and head wounds). Only an elaborate shot through the Unisphere in Flushing doesn’t fit the aesthetic, whereas the rest of the movie proves immersive and unfussily stylized.

Whatever one may think of Aronofsky’s choice of material in the past, his work with actors remains impressive. Butler is somewhat recessive as Hank, but playing a normal guy for a change—not a legendary rock star or an alien prince—he has a natural charisma that propels the story and never becomes overwhelmed by the terrific ensemble. Hank can come off as a little detached, especially given his limited response to one shocking death. But it helps that he’s usually accompanied by Bud the cat (who’s a biter and played by Tonic the cat), a scene stealer thanks to those aforementioned reaction shots. Inevitably, Aronofsky cannot resist overstating Caught Stealing’s theme about accountability by playing up the finale with some full-circle imagery and the irony that Hank must repeat past mistakes to resolve the situation. To whatever degree the narrative and visuals deliver a kind of literary closure that doesn’t translate well to cinema in this context and feels overly symmetrical, Aronofsky balances his film’s heavier, bleaker ideas with humor and energy—a welcome change of pace for the director.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review