Traumatika

By Brian Eggert |

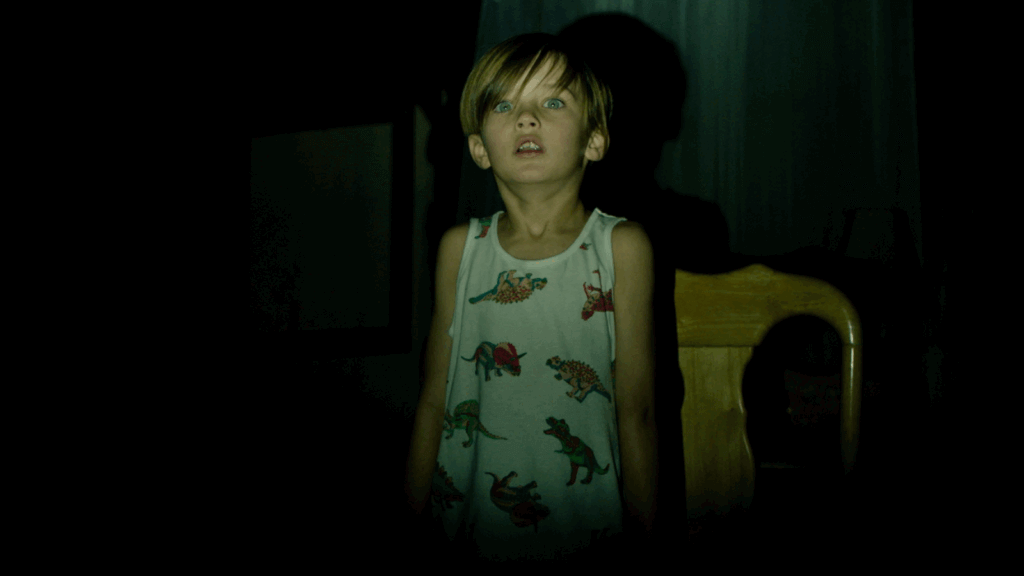

Traumatika is the emptiest movie I’ve seen in some time. I can think of nothing about it that warrants a recommendation. It’s another supernatural horror movie that uses the theme of emotional trauma to justify depicting spooky situations and gory kills. After all, trauma is in the title (followed by the Greek suffix ika, literally meaning pertaining to). It’s an increasingly tiresome trend, but depending on the execution, it can be done well (see this year’s Bring Her Back). However, this movie is particularly abhorrent, not only because it attempts to elevate itself with the theme of children in peril—as a lot of horror movies do—but because of its incompetence. Not one character, not one choice, not one moment is convincing. A good horror movie can function like therapy, providing a catharsis that purges repressed emotions and banishes inner demons. A horror movie as bad as Traumatika purges only 80 or so minutes from our finite lifespan.

The movie has a narrative structure that is inorganic and downright baffling. By the end—including a cryptic prologue set in Egypt in 1910, followed by scenes in 2003, 2004, and 2024—I struggled to identify a protagonist. There’s no one to root for, and, with ten minutes left, director Pierre Tsigaridis was still introducing and disposing of characters. The only somewhat consistent presence is Volpaazu, a “dark entity” contained in an Egyptian artifact. Somehow, the artifact ends up with an abusive father (Sean O’Bryan), who releases it despite the warnings of his friend, Steve (Sean Whalen), an exposition dump character who appears in a single scene. Steve reads from a cheap-looking website called creepy-news-dot-com, which warns that Volpaazu is “the universe’s most feared demon.” Based on that claim, it seems that even aliens in galaxies far, far away know about this thing.

We learn that the demon’s modus operandi involves possessing children and spreading itself across many victims, like an infection—but we learn this not because the movie has shown it to us; Steve explains it. What drives the demon to do this isn’t clear, other than demons are demons, and they’re not known for their nice behavior. Those plagued by Volpaazu have nasty-looking boils on their face and body; they ooze black stuff from their eyes and mouth; they spider-walk on ceilings. There is even a demon dance: One scene follows a doomed cop, played by horror regular AJ Bowen, who descends into a creepy basement. Once down there, he finds the bodies of several dead children. All at once, a possessed woman (Rebekah Kennedy) appears behind him, dances a jig worthy of a Deadite from the Evil Dead series, and attacks. I laughed, mostly out of bewilderment. Later, when we see the full demon, it has gray-blue skin and dons a red loincloth. Then it roars in a manner that, much like the dance, prompted me to laugh for reasons the movie did not intend.

Except, this isn’t a so-bad-it’s-good movie. It’s a just-plain-bad movie. Traumatika doesn’t even do the audience the service of deploying genre clichés or tired formulas, which can be entertaining, even in their lowest of lowbrow states. Perhaps the filmmakers of this movie would justify the attempt by calling the structure “unconventional” or “experimental” or some other similar term to explain away the fragmented storytelling at work. But there’s no sense of reality or humanity here. The story is disjointed and conjures no emotional response, except for confusion, boredom, and then, finally, disgust over its inability to connect. Then again, I felt sympathy for the actors, who have only thankless, throwaway scenes to perform. Few of their scenes build into something more or contribute to the whole. It’s all the more frustrating that the movie descends into a random masked killer finale that offers no resolution whatsoever.

Watching the movie, I could smell a whiff of a story about a woman (Emily Goss) who was traumatized as a child when the demon possessed her family, and then she grew up to face the specter of her trauma once more. That’s a standard plot I’ve seen plenty of times. However, Tsigaridis, who also serves as cinematographer and editor, seems unable or unwilling to develop that narrative path and guide the viewer down it. He has no sense of subjectivity, clunky character POV shots notwithstanding. He arranges the events in such a way that neither establishes well-drawn characters nor pulled me into the terror. Things just seem to happen. It’s as though Tsigaridis’ budget ran out halfway through production or he lost a third of the footage he shot, because the connective tissue from one scene to the next is missing. And if these are choices he has made with what he had, they are unwise choices.

At the very least, Saban Films’ promotional department deserves credit for Traumatika’s sensationalist tagline: “This is not a movie you see! This is a movie you survive!” Indeed, it’s less a cinematic experience than an endurance test, yet not in the rewarding manner of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) or Possession (1981). It has more in common with A Serbian Film (2009) and The Human Centipede series—movies that are more interested in gimmicks and gnarly displays than in telling a worthwhile story. To be sure, this is a violent, ugly movie, which is made all the worse by its utter lack of narrative cohesion. Even as Tsigaridis and co-writer Maxime Rançon attempt to instill gravitas with their deliberate exploitation of the audience’s aversion to seeing children in peril, they deliver only a base, hollow experience. It’s not that a story about a demon who preys on children is off-limits; rather, the topic has been treated with such a disregard for characters and narrative thrust that I was hard-pressed to care.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review