F1

By Brian Eggert |

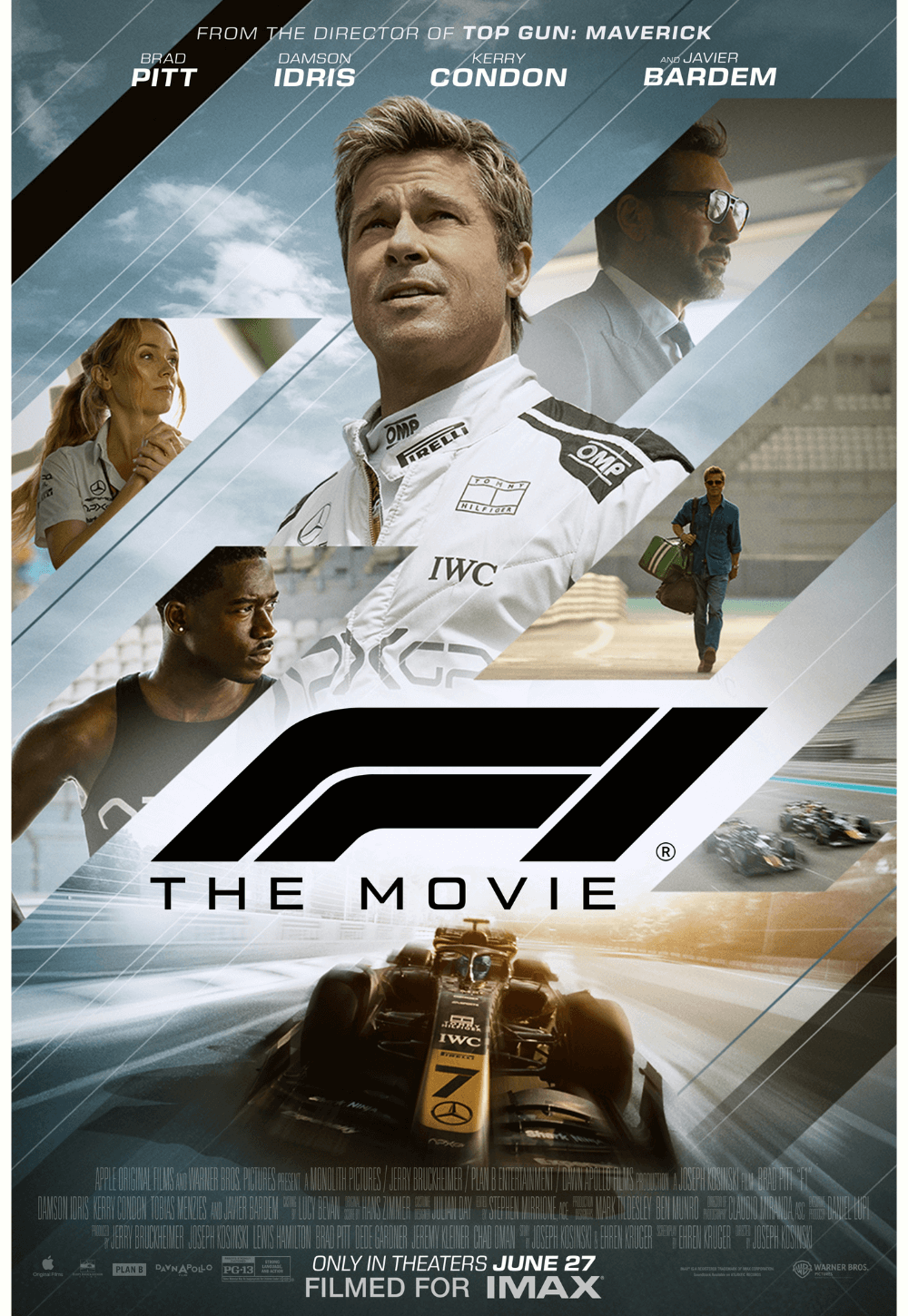

“Why do we do this?” asks Reuben, a Formula One driver turned team owner. Played by Javier Bardem, whose presence exudes warmth and heart, Reuben raises a question that I asked myself a few times about the characters during F1, director Joseph Kosinski’s crowd-pleasing racing spectacle. The drivers and engineers in the movie each provide one-dimensional answers at best. Some like the fame, fortune, and followers on social media; some like the challenge of designing a better car; some even take a cue from Ricky Bobby and just want to go fast, to experience the danger and adrenaline, which makes them feel alive. Movies about racing—from Grand Prix (1967) to Rush (2013)—need great human drama to cut through the vroom-vroom monotony. After all, the cars can only go around on the same tracks so many times before they become tedious; there had better be some emotional stakes onscreen. F1 doesn’t stretch itself in that department. Fortunately, between the jaw-clenching tension of the racing sequences and a cheer-worthy finale, the movie manages to implant some humanity into the proceedings, however simplistic and curiously familiar.

Indeed, as F1 conforms to the sports movie template, Kosinski and screenwriter Ehren Kruger apply the story structure from their last collaboration, Top Gun: Maverick (2022). Place the blueprints of both movies over each other, and they almost perfectly align. The filmmakers replace high-speed jets with high-speed racecars, and a naval air mission with a worldwide racing competition. Both movies involve a team with an impossible task, only to have an aging, yet still daring, virtuoso teach them a new (but reckless) way of doing things. Both movies tout themes of teamwork over individualism. For their conflicts, both favor an objective over a villain—the bad guys in Maverick remain faceless, while the drivers in F1 fight internal battles more than a single competing driver. Both feature an older protagonist who clashes with a young hotshot when he’s not grappling with his past. Along the way, both men learn something from the other generation. And yet, despite the similarities, Kosinski delivers another visual extravaganza—a moviegoing experience that must be seen on the big screen, because it probably won’t be as engaging on television or smaller devices. (Then again, what movie is?)

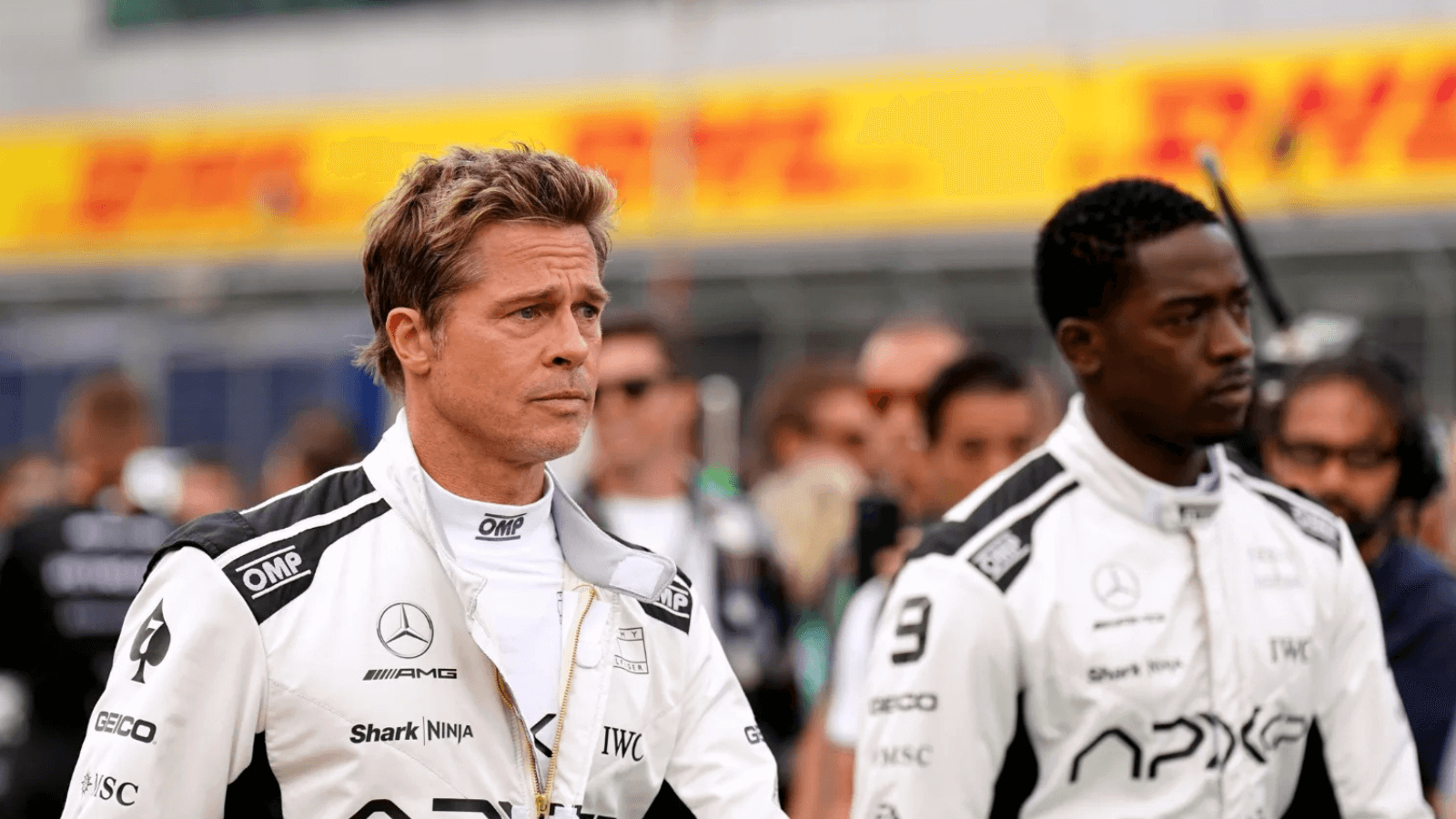

Brad Pitt plays Sonny Hayes, a former racer who coulda been a contender, except a devastating crash at a Formula One race in the 1990s left his body shattered and his career in ruins. The character might be a vacuum if not for Pitt, whose charm, swagger, and vulnerable underpinnings lend Sonny humanity. He’s the old underdog with two divorces, a gambling addiction, and a whole bunch of regrets that prompt nightmares (strangely visualized in analog video). As one person remarks, Sonny isn’t a has-been; he’s a never-was. He now lives in a rickety van and spends his life starting over, traveling from one race to the next, driving in his “high-stakes gambling style.” After he wins a gig-for-hire at the Daytona 500 that earns him some attention, Sonny receives a visit from his former competitor and friend, Reuben, who runs APXGP—a Formula One company that, thanks to a “shitbox” car and a $350 million hole, could be taken away from him by its board. To remain in Reuben’s control, the team must win one of the remaining nine races in the current Formula One season. Sonny agrees, not for the trophies or glory, but partly to make up for his past, and partly for the rush.

What follows is a movie with clichés to spare, but the compelling performances and energetic filmmaking do much to distract from the familiar template. Sonny clashes with Joshua Pearce (Damson Idris), the team’s young and cocky driver, who’s initially more interested in the spotlight than learning from his teammate. Kerry Condon plays Kate, a former Lockheed engineer who hopes to design a more aerodynamic car to give the team’s drivers a tenth-of-a-second advantage. There’s an obligatory romantic subplot between Sonny and Kate, and another subplot about Joshua’s mother (Sarah Niles) blaming Sonny for an accident, which, as it turns out, isn’t his fault. The story takes the team around the world to various Formula One racetracks, and all the while, the usual training and racing montages play like music videos. And if you don’t understand the dynamics of racing, no worries. Kruger’s script relies heavily on race commentators via ADR to explain the ins and outs of what’s at stake. Even so, there were times when I—no fan of sports or automobiles—felt confused about the rules of Formula One and the technical aspects of the cars. But some experts have attested to the movie’s authenticity.

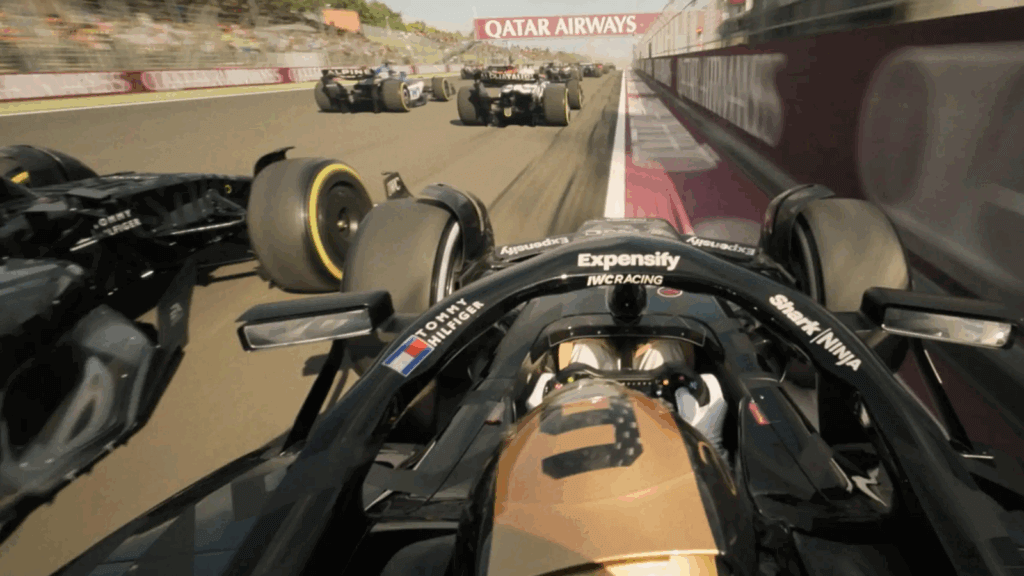

Collaborating with his regular cinematographer, Claudio Miranda, who has shot each of the director’s earlier films, Kosinski employs IMAX cameras to capture the scope and speed of the races. Similar to their approach on Maverick that put viewers in the pilot’s seat, the filmmakers craft driver POV shots and in-car cameras to evoke the dizzying speeds, humming vehicle frames, and, inevitably, breathless accidents. The effect is immersive; the cars and races look real, as opposed to a CGI fest, and the illusion never shatters. And while Stephen Mirrione’s editing captures the energy on the track, his distractingly zippy cutting style continues in dramatic scenes, failing to lend them the same urgency. However, Hans Zimmer’s electronic score supplies a more invigorating touch with an uncharacteristic head-bobbing tempo—a sound reminiscent of scores by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. When in doubt and in need of visual punctuation, Kosinski and Mirrione cut to fireworks, the flashy visual equivalent of waving a rattle in front of a baby.

Does Sonny win the race? Does he get the girl? Do he and Joshua finally become pals? Do they save the company? Do they learn valuable lessons along the way? I won’t spoil F1, but most of the answers won’t surprise you. One of the movie’s producers, Jerry Bruckheimer, also produced director Tony Scott’s Days of Thunder (1990), and most of the conflicts in Kosinski’s movie were also covered in that one. Kosinski’s direction even has a kineticism that recalls Scott’s work. Despite the well-treaded material and predictable story beats, Zimmer’s thumping, propulsive score and the slick racing scenes elevate F1. I also cannot overstate how well the cast sells their characters and legitimizes their scenes. Anyone with a lesser talent and charisma than Pitt, Bardem, Condon, and Idris might have made the experience empty. And while it’s not something I expect ever to revisit, F1 is the sort of movie that should be seen on the biggest screen possible, with armfuls of junk food, in a packed theater. In any other situation, it might not work. But in those conditions, it’s quite a show.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review