The Labyrinth of Memory in Chris Marker’s La Jetée

By Maaisha Osman | July 29, 2024

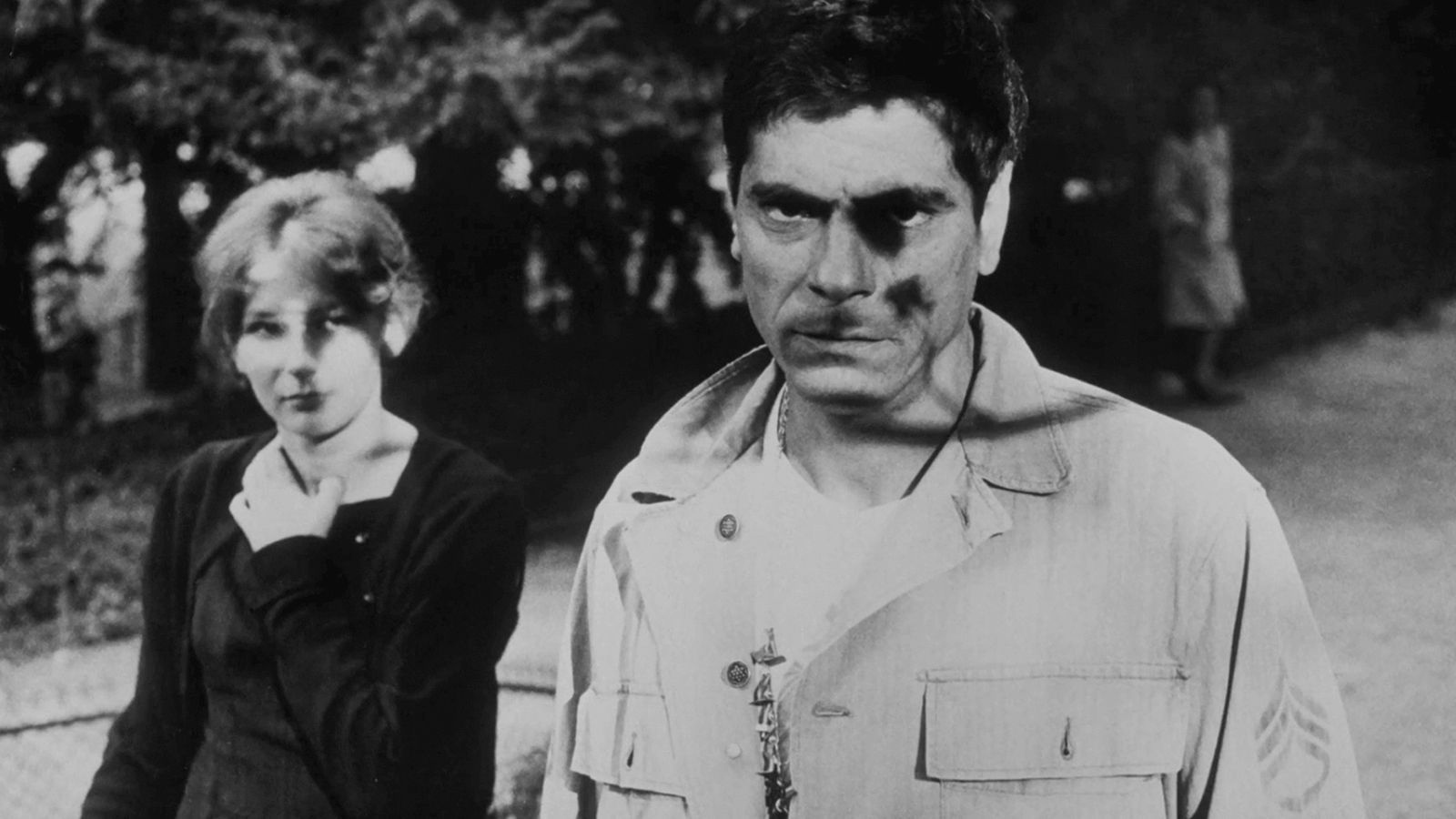

La Jetée (1962) is a tale of memory. It’s a film about how memories shape our identity and perceptions of reality. In 28 minutes, through its innovative use of cinematic techniques with stilled shots and recursive narration, Chris Marker invites viewers to contemplate the intricate relationship between time, memory, and the essence of being. It is a love letter to the eerie power of images that haunt our memory throughout this lifetime.

Through Marker’s adept use of time as a narrative tool, the film transcends traditional cinematic boundaries, offering a transformative viewing experience. In futuristic documentary-like reels, Marker uses black-and-white photographs he had taken during the Second World War to lay out a dystopian world set after the Third World War’s nuclear holocaust. This leads to the survivors retreating to the underground galleries of Paris, where government scientists subject their survivors to experiments in time travel.

Narrated by Jean Negroni, La Jetée tells the story of one of the survivors, an underling forced to travel to the past and the future by scientists desperate for salvation. The man is drawn to relive his most haunting childhood memory: the glimpse of a woman waiting on the landing pier—the titular jetée—of Orly Airport. A memory of a pre-war Paris is stuck in his mind: the smiling silhouette of the woman, quickly followed by the traumatic view of a man dying, shot as he ran towards her. It is this obdurate remembrance that attaches the man to the past, giving him powerful mental images that make him suitable for time travel.

We see him being injected, and the camera gradually transitions to show him lying in a hammock with his eyes covered. The scientist tells the man that the human race is doomed, and the only way to survive is to summon the past and the future to aid the present. Through time travel to the past, he meets the woman and spends tender moments with her. But their love is interrupted by the scientists’ measurements and calibrations of time travel. Ultimately, their love is made impossible when the experimenters determine that the man should travel no longer to the past but to the post-atomic time, where future survivors may reveal to him a vital energy source to heal the shattered present.

Marker’s portrayal of underground scientists in the film suggests how humankind is always ready to exploit—even one’s memory—for control. It symbolizes a dark chapter in the history of the future, a dystopian reality where the human mind is manipulated by a surveillance state.

Marker’s portrayal of underground scientists in the film suggests how humankind is always ready to exploit—even one’s memory—for control. It symbolizes a dark chapter in the history of the future, a dystopian reality where the human mind is manipulated by a surveillance state.

In his book Matter and Memory, Henri Bergson proposed that perception and memory are interconnected, arguing that stored memories are not comprised of static images but rather dynamic experiences that relate to perception, allowing for a more fluid understanding of consciousness. However, in Marker’s narrative, time travel functions as a playback mechanism akin to a gramophone, devoid of introspective capabilities, highlighting the scientists’ quest to exploit the disparity between perception-action and memory-image for control rather than as a manifestation of free will.

The stilled images in the time travel sequences give a documented quality to the film, accentuated by their graininess, as if the film suggests that these people once existed and were caught by these photographs, a partial record of their time on earth. Such images stir our unconscious feelings and give us reassurance that these people are not dead after all.

In Marker’s 1983 film Sans Soleil, he describes the act of remembering: “I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but its lining. We do not remember. We rewrite memory as much as history is rewritten.”

Marker seemed to have a profound understanding that photography, memory, and time form a braid—photography, the method; memory, the result; and time travel, where they intertwine. In La Jetée, the images bear the scars of time—grain, scratches, and dust weave through them. Some are veiled in haze, faded like distant echoes of childhood memories amidst a lifetime’s collection. In each frame, Marker shows the tender moments in a mundane world: a man gazing at a woman’s neck as she sweeps her hair; a boy perched on a guardrail to have a clearer glimpse of the world below; an empty bedroom, frozen in peacetime, now a relic of the past.

In La Jetée, the conception of memory, and thus time, is depicted as a spiral—paradoxical and relentless, as our protagonist discovers. The narration unfolds: “He realised there was no escape out of time, and that the moment he’d been granted to see as a child, and that had obsessed him forever was the moment of his own death.”

The film heavily relies as much on Marker’s unsettling soundscape as it does on black-and-white photographs. La Jetée is a mosaic of still images—ruined buildings, graves, preserved animals, a man falling to the ground, and a mysterious woman depicting the fragility of time—interwoven with whispering sounds, a chorus of songbirds, the rhythmic cadence of heartbeats, musical compositions, and voiceover. In the beginning, Marker situates us in an environment with familiar sounds where we hear an airplane’s engine roar and a woman’s voice on a loudspeaker in Orly airportwhere the film’s protagonist was forever marked by his haunting memory. Marker uses German whispers to depict the scientists’ scheming and plotting. The whispers echo like drops of water in a deserted alley until they are interrupted by the protagonist’s pounding heartbeat.

The film heavily relies as much on Marker’s unsettling soundscape as it does on black-and-white photographs. La Jetée is a mosaic of still images—ruined buildings, graves, preserved animals, a man falling to the ground, and a mysterious woman depicting the fragility of time—interwoven with whispering sounds, a chorus of songbirds, the rhythmic cadence of heartbeats, musical compositions, and voiceover. In the beginning, Marker situates us in an environment with familiar sounds where we hear an airplane’s engine roar and a woman’s voice on a loudspeaker in Orly airportwhere the film’s protagonist was forever marked by his haunting memory. Marker uses German whispers to depict the scientists’ scheming and plotting. The whispers echo like drops of water in a deserted alley until they are interrupted by the protagonist’s pounding heartbeat.

These sounds are evocative, but the music is trancelike. Trevor Duncan’s score is integral to defining the essence of La Jetée as a mosaic of memories. While it employs a minimalist approach reminiscent of Stravinsky, its standout feature is the romantic theme, reminiscent of Bernard Herrmann’s mysterious soundtrack for Vertigo (1958). But the film’s foreground use of sound is its narration. The narrator’s voice carries neither irony nor earnestness; instead, its affectless tone is both comforting and unsettling.

In the man’s voyage to the past, he encounters the woman at various times. He remembers their walks through Paris visits to the museum of natural history, and watching her sleep under the sunlight—the tender moments in life. But Marker questions his memory: Is he inventing those tender moments to survive the present? The film further delves into the existential implications of memory, highlighting its role in defining individual identity and existence. The protagonist’s journey is not merely a quest to recover lost fragments of the past but also a search for meaning and purpose within a world ravaged by destruction.

Throughout the film, images of the mysterious woman evoke a sense of intimacy and detachment. She reminds us of the profound impact of love on our memories. The most striking moment in the film is the only moving image, where the woman’s soft glance in the penumbra of a bedroom is inexplicably juxtaposed with a chorus of birds. This lyrical moment is briskly interrupted by the camera cutting back to the bleak present, where there are no birds or signs of life. It highlights the man’s fleeting proximity to truly living in that moment with her—a moment cut off just like the scientists sever his tenuous and barely established connection to the past by thrusting him back into the unforgiving present.

Throughout the film, images of the mysterious woman evoke a sense of intimacy and detachment. She reminds us of the profound impact of love on our memories. The most striking moment in the film is the only moving image, where the woman’s soft glance in the penumbra of a bedroom is inexplicably juxtaposed with a chorus of birds. This lyrical moment is briskly interrupted by the camera cutting back to the bleak present, where there are no birds or signs of life. It highlights the man’s fleeting proximity to truly living in that moment with her—a moment cut off just like the scientists sever his tenuous and barely established connection to the past by thrusting him back into the unforgiving present.

In the future, the man meets some unusual people with surgical implants on their faces that give him blueprints for the scientists. After returning these blueprints, he realizes he is no longer of use and will be executed. It is then that the strangers from the future appear to him, offering him a chance to reach salvation in the future. The man instead asks the strangers to send him to the past of his childhood, yearning only to be reunited with the woman. This time, he travels to the past in Orly Airport, where we learn that he was the dying man in his childhood memory, shot by the scientists while running towards the woman. In this pivotal instant, long fixated upon since childhood, he captures the immutable truth: his inescapable demise.

Time, in and of itself, is often thought to reveal the essence of things. The Japanese find beauty in the deepened hue of ancient trees, the weathered texture of moss on old stones, and the worn edges of frequently handled photographs. This perspective about the world, known as sabi, a term that translates to rust, refers to this evidence. La Jetée embodies this concept of sabi, wherein time becomes a new muse for artistic expression.

Marker seems to embrace the concept of sabi in his work, using old rusty photographs of real life and repurposing them into fictional sci-fi elements to convey the complexities of time and memory on screen. Through this, Marker aimed to master time as the essence of art.

The film also inspired other filmmakers like Terry Gilliam, whose 1995 film 12 Monkeys emulates La Jetée in a strikingly innovative manner, with a technological bent and Gilliam’s distinct stylistic tendencies.

After half a century, it is still difficult to say what Marker achieved in this film. He explores how memories are multifaceted, recalling what Marcel Proust described of his grandmother: “Even when she had to make someone an ostensibly practical gift, when she had to give an armchair, a dinner service or a walking stick, she would look out for old ones as if these, purged by long disuse of their utilitarian character, were able to tell us how people had lived in the old days, rather than serve our modern needs.” This is what it seems to me Marker has captured in this film.

Bibliography:

Bergson, Henri, Nancy Margaret Trans Paul, and W. Palmer. “Of the survival of images. Memory and mind.” (1911).

Koresky, Michael, Moore, Casey. “Listening to La Jetée.” (2012)

Maaisha Osman is a health care policy journalist based in Washington D.C. She has written for Inside Health Policy, STAT, and Point of View Magazine. A lifelong cinéphile, she dreams of writing book of essays on films by her favorite directors like Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, Satyajit Ray, Rwitik Ghatak, François Truffaut, Wong Kar-wai, and others.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review