Sundance Recap and Reviews – Part 3

By Beau Stucki | February 20, 2019

Precariously situated in the icy mountains of northern Utah, the Sundance Film Festival is a haven for movie-lovers bold enough to crowd the small city during the snow-blown winter. The festival was founded by a-lister Robert Redford but prides itself as a champion for diverse independent cinema. The marketing this year was themed around “Risk” and that was reflected in the movie choices – for better and worse.

Over 2,000 feature films and more than 9,000 short films were submitted. Of those, only 112 of the former and 73 of the latter made the cut. Sundance is a competition and distribution festival – so the studio representatives were there, ready to purchase. Netflix, Amazon, A24, HBO, Sony, and others bought up titles you can expect to be hitting the big and small screen throughout the year.

In my first season attending as a member of the press, I was able to see just over 30 titles during the 10-day event.

My reviews will be published in three parts. Check out Part 1 and Part 2.

Honey Boy

Honey Boy

US Dramatic Competition

Shia LaBeouf’s self-reflexive tale (despite capable direction from Alma Har’el this is destined to be known as LaBeouf’s movie) adds a new layer to that genre of films in which cinema thinks about cinema. Like Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up (1990), Honey Boy is a movie whose concept inspires conversation without even being watched.

LaBeouf has penned a story about his own life and the fraught relationship he had with his father during his childhood years. In this story, he plays his own father, and his character is in turn played by actors Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges at their respective ages.

There is self-depreciation throughout the meta-movie. Like most artists of note, LaBeouf is observant of his own faults, and he’s aware of the jokes and memes made about his early days in the teenage action epics of Michael Bay. If the movie is also indulgent or ego-centric it is still compelling—which is the great absolution in art, the sin for which we forgive all others.

Yet there are niggling problems we cannot escape pondering. There is the question of misplaced affection and sensual experiences—there’s a difference of age in one where, if the genders were reversed, it would doubtless be the subject of outcry. And for a movie that painfully reminds us what children are sometimes put through as those the people love pursue public relevance or fame and fortune, we cannot help but wonder what the young actor Jupe is going through as he plays out these traumatic experiences. To be sure, acting and experiencing are not the same—but I think most of us would think twice about putting a child through scenes we might not let them watch.

Honey Boy is sure to be a part of any discussion on movies as self-portraits. 3/4 Stars.

Them That Follow

Them That Follow

US Dramatic Competition

Them That Follow is an ominous melodrama that seeks nuance among characters in a small community of Pentecostal snake handlers—people who handle venomous snakes as a religious rite, based on an interpretation of biblical verse: “And these signs will accompany those who believe […] they will pick up serpents with their hands; and if they drink any deadly poison, it will not hurt them, they will lay their hands on the sick, and they will recover.”

The cast features a good half-dozen of the talented sort of small-timers who are able to grab all sorts of interesting roles precisely because they themselves aren’t yet household names—though you will know most of their faces. Walton Goggins portrays the pastor of this community. Olivia Colman is a convert from a worldly past. Alice Englert carries the film, and her character holds the choices that decide the fate of many others.

Over the past few decades, the lion’s share of movies that consider Christianity tend to be one of two sorts. Either they are made mawkishly by faith peddlers and don’t have enough artistry to keep from being sappy and trite. Or they are aggressively cynical in a way that is meant to be provocative but is really quite dully overdone. The relief of Them That Follow is that it is not entirely dismissive of Christian belief or faith—and this is even with a fringe sect about which it is all the more easy to write off as completely insane.

But insanity is seldom the real story—even with something as lamentable as the handling of deadly serpents. Often when we call someone insane what we really do is admit we lack the proper empathy or information to understand. If this movie does pull from this or that stereotype, at its heart, it is still an attempt to understand a faith that for all its Americanness is really quite foreign. 3/4 Stars.

Judy and Punch

Judy and Punch

World Cinema Dramatic Competition

Judy and Punch is a punkish, anachronistic tale of crime and punishment. A young couple (Mia Wasikowska and Damon Herriman) take us through a re-imagining of the origins of the famous Punch & Judy puppet shows as it plays against a disastrous marriage—disastrous because one character is the exaggeration of a saint and the other an exaggeration of evil. We don’t know this yet, but we soon will.

The opening scene shows us a theater performance of the two happy puppeteers with intriguing composition—the camerawork is surreal and engaging. The characters, costumes, sights, and sounds are all delightfully strange. Both audiences are hooked and eager to see where all of this will lead. But this fantastical Gilliam-esque wonderland crumbles to little more than a stage for a stilted play on gender roles and a perplexingly contradictory treatise on violence as entertainment.

The movie does not keep up the steam it has at the beginning and undergoes several shifts in tone and theme. The humor is sometimes caustic and other times childish. Motivations rise and fall out of significance. It wants to have a moral, but cannot quite seem to pick out what that moral ought to be. The result is something which strongly resembles darkly comic poignancy, but is much more like an illusory puff of magic smoke Punch might have used in his act.

It is patronizing for a critic to say the director will get there eventually, but this is truly a case where one feels a significant creative talent got lost in the complexity of their first feature film. 2/4 Stars.

Love, Antosha

Love, Antosha

Documentary Premieres

In June of 2016, a rising star of Hollywood was extinguished in a freak accident. At age 27 Anton Yelchin was most well known for his role as Chekov in the Star Trek reboot movies. This documentary shows us that not only was there (of course) much more to the man than a handsome face and a hit role, there was also much more to his career.

Home video footage serves as our introduction to the movie—and betrays the closeness of a small family. Anton (or Antosha) was the only child of his parents, Jewish refugees from the USSR. They were both stars themselves—in the Leningrad Ice Ballet—and supportive of the arts their son adopted. He was their only child and throughout his life they maintained a remarkable, even touching, closeness. The title Love, Antosha is a reference to the valediction on the many letters he wrote to his parents throughout his life.

The movie shows us a man brimming with energy and with curiosity—too much for his own good, at times perhaps. He was a Criterion Collector, a film buff, a photographer, a musician, a man given to much philosophical pondering, and an artist who was directing his first film before the tragic accident that took his life. He first appeared in films as a child, and the parade of famous faces who show up in various interviews throughout the movie make us all the more surprised that we were not more familiar with his career before Star Trek.

Even taking into account the rosiness with which we regard the dead, it is apparent this was a vivacious conversationalist and a man deeply admired and liked by those with whom he worked.

Yelchin’s many younger fans may have to wait to see the film—we are shown some of his experimentation with erotic photography and that is sure to give the film an “R” or “Mature” rating. 3/4 Stars.

Untitled Amazing Johnathan Documentary

Untitled Amazing Johnathan Documentary

US Documentary Competition

A beloved performer is dying. In 2014 doctors told him he had a year to live, and then he told the world, live on stage, before stepping out of the spotlight and into an obscurity of addiction and mystery … waiting for a death that does not come.

Untitled starts as a straightforward piece on the life of the wild and irreverent stage magician but quickly become a loose and labyrinthine exploration on the ethics and authenticity of documentary filmmaking. It’s a piecemeal treatment that is exploitative and almost narcissistic. It’s also entertaining, funny, and consistently surprising.

It isn’t any sort of a spoiler to say Untitled smacks of Orson Welles’ visual essay F for Fake—albeit filtered through the sensibilities we might expect from Ben Berman—who is one of the directors behind the Comedy Bang! Bang! TV series. There is a lot of meta-musing and an increasingly intrusive shift in the topic and characters of the story.

The less said of the film before viewing, the better. Afterward, you will have questions about truth, about gimmicks, about sneaky storytelling, and about a singular man known as The Amazing Johnathan. 3/4 Stars.

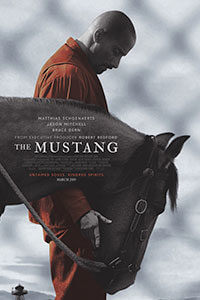

The Mustang

The Mustang

Premieres

The Mustang is the debut feature of writer-director Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre. Hitherto an actress in French cinema, she nevertheless tells a distinctly American tale. It’s a slightly saccharine story about imprisonment—the kind society imposes on us and the kind we impose upon ourselves.

Matthias Schoenaerts plays Roman, a hot-headed inmate in a Nevada prison—so hot-headed that he is frequently restricted to solitary confinement. It’s a condition he seems to prefer over enduring the company of his fellow man. Change in his routine of unending frustrations occurs when he is worked into a rehabilitation program which allows convicts to train newly-captured wild mustangs (under the management of a gruff cowboy played by Bruce Dern).

The development has many moments we have seen before in other movies, but there is interest too. Despite the camera cutting in close when we would like to see the wider picture, the interactions with the horses are impressively handled. It is true that the metaphor between unbroken horse and broken man is a bit on the nose, but the performances are strong, and the movie resists the temptation to make tedious political statements.

It is not an insult to say the movie puts us in a mind to watch the great films about the relationship between animals and humans—movies like Kes (1969) or even The Black Stallion (1979). The Mustang is not one of these great films, but it has captured aspects of that spirit and evokes a passion we hope to see more of in Clermont-Tonnerre’s future work. 3/4 Stars.

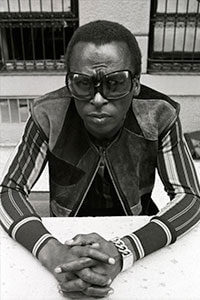

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool

Documentary Premieres

Birth of Cool is a simple re-telling of the life of mega-star Miles Davis. Told with the aid of that treasure so sought by documentarians—never-before-seen footage.

“Music has always been a curse to me,” rattles Davis in his oft-imitated raspy whisper as the movie opens. Cursed or not, his 65 years were rife with the sort of trouble and misfortune we have come to expect from artists operating in the spotlight and at his level of musical ability. Despite the acknowledgment of his vices, the documentary is not especially salacious or scandalous. We are shown his struggle with drug addiction and the tumultuous up-and-down of his domestic relationships, but that isn’t the focus and we do not dawdle—there’s a lot of ground to be covered in the two-hour runtime.

The movie takes us from the 1920s into the 1990s, with highlight montages to establish the context of American culture at each decade. We see Davis change with the times. The movie tells us nothing if not that Davis had a genius for artistic adaptation. He is at times king of bebop, at times a rock-n-roller, even at one time a composer for the soundtrack of the classic French thriller Elevator to the Gallows (1958).

There is an admirable attempt to refrain from editorializing Davis’ life, but we are given such a wide tapestry of information that we could stand for a thread to hang on to—a stronger theme or angle to help us process so very many details. But it can also be said that there is nothing we are left to wonder about—in that sense it may very well be a definitive work. One which gives us as complete a biography as we are likely to get. The only thing left to seek is his music. 3/4 Stars.

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

Premieres

Inspirational epics based on true stories have to be en garde against the traps of winsome cliché and a propensity to shy so far away from darkness and fault that we cannot recognize the world the movie creates. The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind is almost entirely free of both problems, and its authenticity (in production and theme) allows us to check our cynicism and open up for what we know is coming.

Chiwetel Ejiofor’s first feature film as a director follows real-life events in Malawi. Earlier this century the country’s corrupt government pushed the already impoverished population to dire circumstances. Many desperate, starving people turned to looting, fleeing, or simply despairing.

For young William Kamkwamba (Maxwell Simba) and his family of farmers, life or death is a gamble—if the weather is good there is food and money, if not… But William has a scientific curiosity and a knack for building and tinkering which gives him an idea, a way to pull control a little farther away from nature and bring hope to his community.

From his years as one of the cinema’s most engaging actors, Ejiofor has developed a potent sense of drama and how to find it in every scene. He elicits strong performances from each cast member, including himself. His presentation is classical—a smooth and steady frame without the jostling of a steady-cam or the whoosh of a zoom. Great care is given to the accuracy of the setting, language, costumes, and points of view—or at least we are given to feel it is accurate, which for a movie is more important.

On the whole, the film achieves its aims—it is epic and, through keenly felt trials, it is inspirational. 3.5/4 Stars.

DOCUMENTARY SHORTS

Black 14

Black 14 is an assemblage of news footage from Wyoming during the Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s. Black college athletes who wanted to protest against Brigham Young University due to issues of race were removed from the team for organizing to discuss the possibility. The story is well sculpted to fit the time and displays a lot of viewpoints we may or may not be shocked to see from the not-so-distant past. 2.5/4 Stars.

Harda (The Tough)

Abandoning speech for the universal language of imagery, documentarian Marcin Polar wordlessly juxtaposes sweeping air footage with claustrophobic dives into a newly discovered cave in the mountains of Poland. It’s a thrilling paragraph on the human drive to explore. 3.5/4 Stars.

Ghosts of Sugar Land *winner of a prize for nonfiction short film

Ghosts of Sugar Land presents an anonymous group of Muslim-Americans bizarrely clad in the masks of iconic figures in Western pop culture. In its brief runtime, we encounter a nuanced and genuine presentation of the Islamic identity crisis that provokes both thought and sympathy by asking all the right questions. 4/4 Stars.

Life Overtakes Me

Refugee children (almost exclusively in Sweden) are suffering from a devastating illness known as Resignation Syndrome. Heartrending and mysterious, this is a story the mind is unable to categorize not only because it deals with a reality we do not want to accept, but because there are as yet so few facts to extrapolate from. It falters slightly by being a tad too long for the amount of information it offers. 3/4 Stars.

NARRATIVE SHORTS

A Gift

A Gift has loose framing over a loose story about identity and youth. The tone is a bit fractured, creating unintended tension and moments that viewers may find hard to follow despite the work of the performers. 2/5 Stars.

Old Haunt

A jaunty little mystery. The presentation is facile and the production value has a run-and-gun feel, but the joke is clever and the chuckles are sustaining. It is an idea one could see being inflated to a feature someday. 2.5/4 Stars.

Manicure

A haunting picture of secrecy and oppression. Overflowing with grimness and deeply sure of its importance—the effect is that we are more overwhelmed than moved. Its photography is memorable and its subtitles are curiously experimental. 2/4 Stars.

How Does It Start

With flamboyant editing and a golden color pallet, this coming of age short gives us a glimpse into the sexual awakening of a 12-year-old girl. It will no-doubt resonate with some, but a few smart narrative choices and admirable acting performances do not excuse the sexualizing of children or their portrayal in erotic acts. It is a personal film, but not all personal experiences are fit for the screen. 1/4 Stars.

Throat Singing in Kangirsuk

A pleasing and pithy venture into the wholesome and exotic music of a culture we seldom see on the screen. It is startling and almost surreal—a music video really—with some pretty drone footage. 3.5/4 Stars.

Brotherhood

In her second short narrative as director, Meryam Joobeur has established herself as one of the most assured voices in the whole cacophony of Sundance 2019. More stylized than Satyajit Ray or Asghar Farhadi but with the similarly refined sense of consequence and empathy. It is this empathy that fires Brotherhood directly into our consciousness even without the level of context we are used to in modern movies. Utterly remarkable and exciting in a director who is presumably at the beginning of an intriguing career. 4/4 Stars.

Beau Stucki is a traveling writer and entrepreneur. He co-runs the film discussion group This Movie Club.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review