Reader's Choice

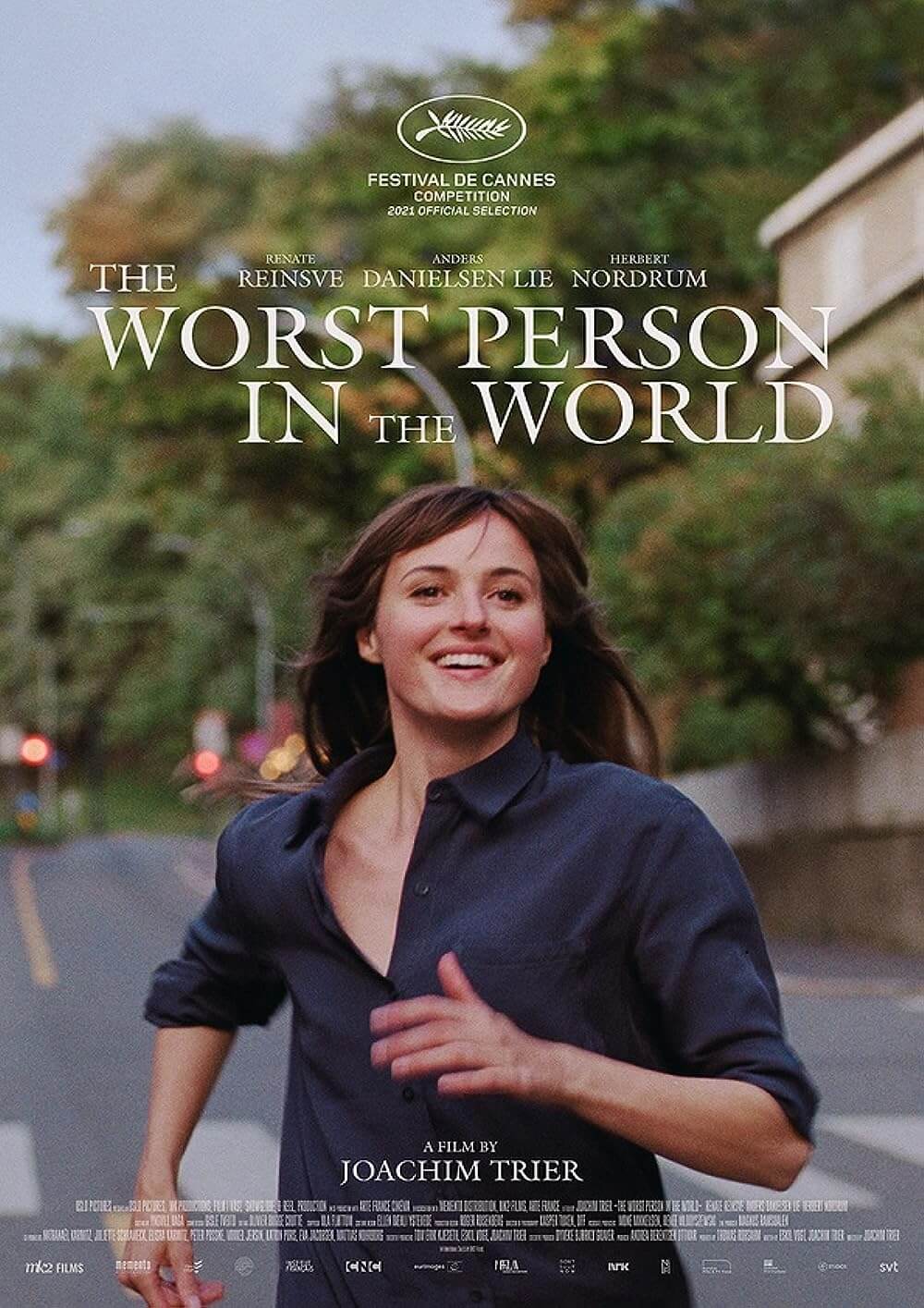

The Worst Person in the World

By Brian Eggert |

In The Worst Person in the World, Renate Reinsve plays Julie, the titular role. With only a few minor credits on her résumé, Reinsve gives a remarkable performance as a young Norwegian woman capable of almost anything. Yet, she resists pointing her life in a single direction. Julie tries her hand at medical school, psychology, and photography in college, achieving good grades even as she realizes they don’t mean squat when it comes to personal fulfillment. And though Julie could have succeeded at any major, she ends up working at a bookstore to discover what truly interests her. “When was life supposed to start?” asks the film’s narrator, channeling Julie’s inner uncertainty. It’s a question many millennials ask themselves, and as time passes, whole chunks of life disappear in the exploration of endless possibilities. For someone like Julie, who’s talented, intelligent, beautiful, and lives in a privileged part of the world, it’s somewhat criminal that she doesn’t make more of herself, hence the title. However, such pressure from expectation, even self-imposed, can be crippling when you have to live with the consequences of the wrong choices. Reinsve captures Julie’s adventurousness and irresolution with incredible humanity, delivering a turn that earned her the Best Actress award at Cannes.

Writer-director Joaquin Trier channels Woody Allen in his portrait of Julie, adopting many of the New York filmmaker’s stylistic and structural mannerisms for a modern story in a much-copied style. Trier’s portrait of millennial indecision and reinvention contains takeaways from Allen’s Annie Hall (1977), Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2009), and Blue Jasmine (2013), borrowing well-established devices for a three-dimensional character study. Julie is the Norwegian female equivalent of many Allen protagonists, fraught with self-doubt and the destructive desire to reinvent herself, ever afraid to miss out on a new form of happiness. The film also contains many of the Allen formal hallmarks: jazz music on the soundtrack, voiceover from an omniscient narrator, an animated sequence, conversations about life among affluent pseudo-intellectuals, and a sprawling narrative set across various segments—12 chapters, not including an epilogue and prologue.

Trier’s film, co-written by Eskil Vogt, captures the fleeting nature of Julie’s twenties in the opening chapter. Julie has a few flings in college and flounders before meeting Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), a 44-year-old underground comic-book artist who wants children. But she isn’t ready. “You seem to be waiting for something,” Aksel observes, trying to convince her that there will never be a right time for children. Aksel’s bourgeois friends talk about Freud and have children, but they’re trapped in a hardly convincing complacency that only confirms Julie’s aversion to parenthood. She dabbles in expressing herself with an essay called “Oral Sex in the Age of #MeToo,” though her essay’s argument is never fully divulged beyond its appeal as a turn-on while also intellectually satisfying. The essay goes viral, but Julie doesn’t do much with that—neither does Trier, who doesn’t explore in detail Julie’s relationship with the internet, a significant facet of millennial existence. Meanwhile, though her relationship with Aksel is deep and meaningful, Julie eventually wants out—because who-knows-what-else might be out there.

The film’s lively middle section where Julie starts to move away from Aksel begins one night when she wanders about the film’s gorgeous Oslo setting and crashes a wedding. Pretending to be a guest, she meets a playful-lug-of-a-barista named Eivind (Herbert Nordrum), and the two proceed to flirt in a strangely romantic sequence. Both a little drunk, both in relationships, they resolve not to cheat on their partners. But how far can they go without cheating (as they define and justify it to themselves, anyway)? They stand close, bite each other, share secrets, smell armpits, and watch each other pee—all oddly intimate and romantic under the circumstances. Julie’s drive to experience something new takes her from Aksel to Eivind, and more experimentation ensues, leading to some psychedelia and a glorious moment where the world freezes in the dream of new love. The film risks portraying Julie only in relation to the men in her life, including an absent father, but she finally receives some independence in the final stretch.

The film’s lively middle section where Julie starts to move away from Aksel begins one night when she wanders about the film’s gorgeous Oslo setting and crashes a wedding. Pretending to be a guest, she meets a playful-lug-of-a-barista named Eivind (Herbert Nordrum), and the two proceed to flirt in a strangely romantic sequence. Both a little drunk, both in relationships, they resolve not to cheat on their partners. But how far can they go without cheating (as they define and justify it to themselves, anyway)? They stand close, bite each other, share secrets, smell armpits, and watch each other pee—all oddly intimate and romantic under the circumstances. Julie’s drive to experience something new takes her from Aksel to Eivind, and more experimentation ensues, leading to some psychedelia and a glorious moment where the world freezes in the dream of new love. The film risks portraying Julie only in relation to the men in her life, including an absent father, but she finally receives some independence in the final stretch.

The last third of The Worst Person in the World is the most conventional yet most emotionally searing portion. Julie’s persistent sense of having missed opportunities is accentuated by a heartrending encounter with Aksel’s mortality. Eviscerated on television by feminist pundits, the now-single Aksel faces scrutiny for his edgy graphic novel series—hilariously turned into a neutered animated film—before a terminal diagnosis. Of these scenes, it must be said that Danielsen Lie (who works as a real-life doctor between acting roles) conveys an astounding degree of humanity and a universal sense of regret about his choices. The moment sparks something in Julie, even if it’s just an acceptance that she will spend part of her life searching. These scenes mark a sobering come-down from the fantasy freeze-frame sequence and mushroom-munching fun in the middle, when the film is at its best and most formally fantastical. The final moments also find an unlikely peace for Julie, who, as much as anyone who has lived on planet Earth, will continue to change, grow, and face life’s many unpredictabilities.

And so, the final sentiment that everything’s gonna be all right feels somewhat empty next to the more relatable pattern of life’s episodes and vacillation that came earlier. Still, just as Woody Allen often does, Trier gets into the mind of his female subject for most of The Worst Person in the World. Reinsve (who works as a carpenter between acting roles) had a small part in Trier’s Oslo, 31 August (2011) and made an impression on the director. After years of keeping in touch, he wrote the role of Julie for her. She turned Julie into a breakout performance that will feel achingly familiar for a generation stunted by too many options and an unwillingness to resign oneself. Heavy as the material may sound, it balances its melancholy with humor and romance, creating an accessible experience with realistic people and their personal crises. About the long process of accepting that some opportunities will be missed, some choices will be regretted, but to keep trying new things, Trier’s film and Reinsve’s performance feel alive and urgently explored.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on January 26, 2022.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review