Reader's Choice

The World

By Brian Eggert |

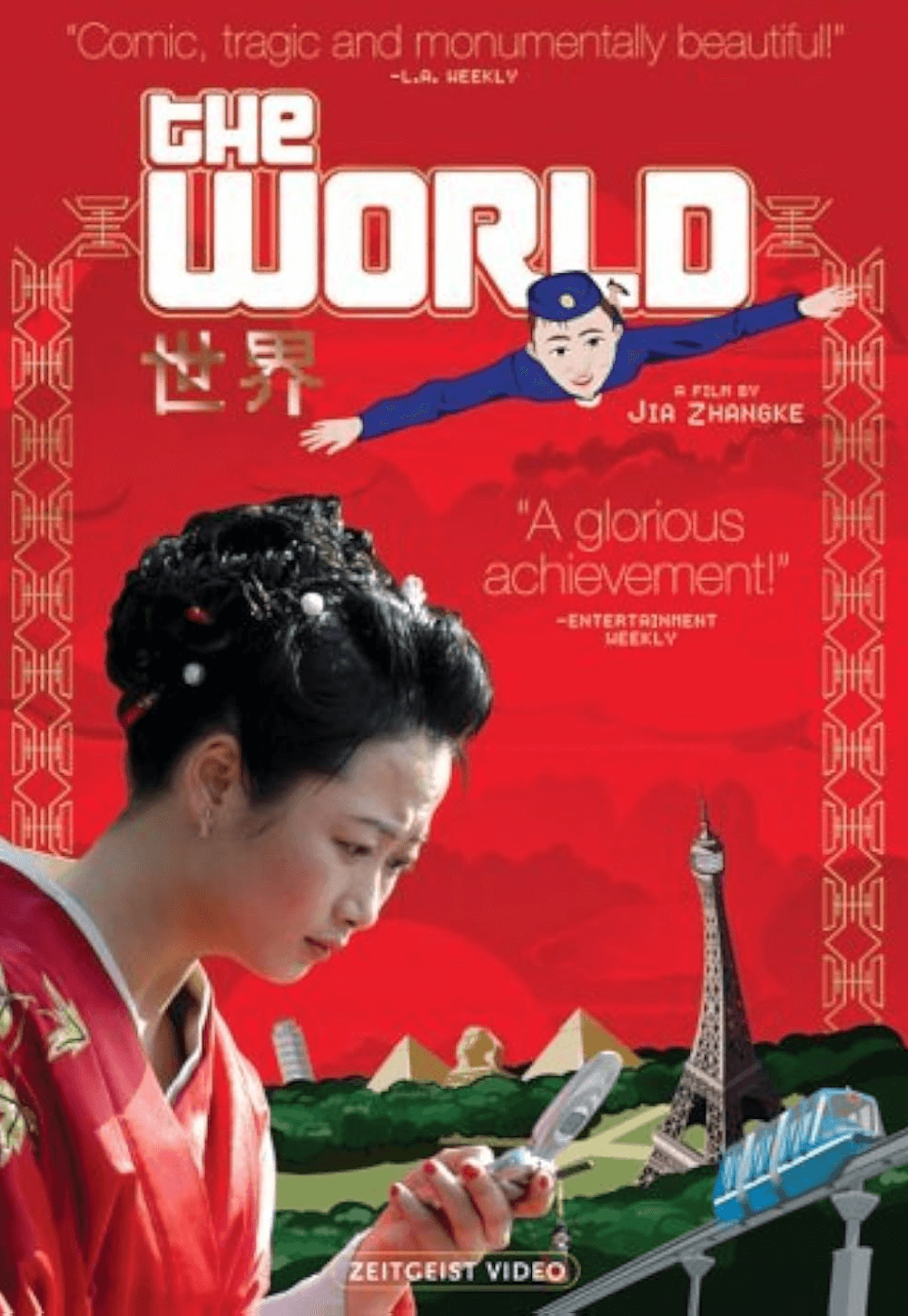

Jia Zhangke’s 2004 film The World takes place around the World Park in the Fengtai District of Beijing. The theme park covers a mere fraction of Disney World’s acreage, yet it features over one hundred scale replicas of famous attractions from more than a dozen countries. Why leave China to see the Great Sphinx in Egypt, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, or the Big Ben Clock Tower in London when they’re all right in Beijing? The World Park even has miniature versions of the Venus de Milo, Michelangelo’s David, and other canonized artworks. Its slogans—“Give us a day, we’ll show you the world” and “See the world without ever leaving Beijing”—suggest a welcoming attitude toward the global community and other cultures. After all, the average Chinese citizen cannot afford to travel across the globe to see the real versions of these sights. The park claims to be a cosmopolitan site of openness to national diversity through an international village. But it also ensnares its visitors and employees, allowing China to control the narrative less by celebrating other cultures than neutralizing wanderlust. However, Jia’s subject is less specific to China than a microcosmic portrait of the world’s inescapable dependence on global market economies.

While the Chinese director doesn’t attempt to resolve the socioeconomic issues raised by The World, his film underscores what Jia calls the “entrapment” at play—in the park, in China, in a world fueled by capitalism. His film is a powerful metaphor for our increasing inability to distinguish between local and global spaces, political and economic ideology, and capitalism’s unifying yet conforming effect. Demonstrated by the worldwide reach of products from Hollywood, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Disney, and others, the world’s major output has been homogenized, leaving only minor examples in art and consumer products with the specificity of uniqueness. Just as the World Park puts on elaborate stage shows to celebrate other countries, the world as a whole comprises cultural and economic bubbles that resemble one another. When that’s all there is, individuality and cultural distinction ceases to become a priority, and there’s no escape from the monotony.

In Unknown Pleasures (2002), the film Jia made before The World, the director explored a similar theme set against the backdrop of promotional stage shows for a company called Mongolian Liquor. But his 2004 feature refines the message with a real-life counterpart—the stranger-than-fiction example of the World Park. Zhao Tao, Jia’s longtime collaborator and spouse, stars as Tao, who first appears backstage in an Indian dress, looking for a Band-Aid. She maneuvers around production workers and security staff, helping zip up someone else’s costume while she searches for a bandage. Finally, she finds one moments before going on stage and performing alongside other “world beauties.” Jia does not dwell on the stage show or allow his audience to be swept up in the spectacle; instead, he returns backstage, where the bustle has turned into silence and empty corridors. The contrast underscores the pressurized subjection such performers endure to fulfill an elaborate pretense—an ersatz vision of Chinese prosperity that illustrates the country’s need to appear modern and globalized.

Jia finds several ways to counter the World Park’s images of progressive multiculturalism, often by training his camera on the park’s employees. When an older garbage collector appears onscreen, his presence contrasts the flashy, extravagant impression the park hopes to convey—and, by design, this striking contrast is what Jia chooses to place “A film by Jia Zhangke” over. In a typical elliptical narrative structure for Jia, The World is a portrait of the World Park’s underpaid employees and those dependent on the place for income, each hoping for something more. Intimate scenes show Tao and her boyfriend, Taisheng (Chen Taisheng), meeting at various spots in the park and in their shared worker bunks. One day, dressed as a flight attendant and sitting with Taisheng in the cockpit of a mock plane, Tao remarks that working in the park will turn her “into a ghost.”

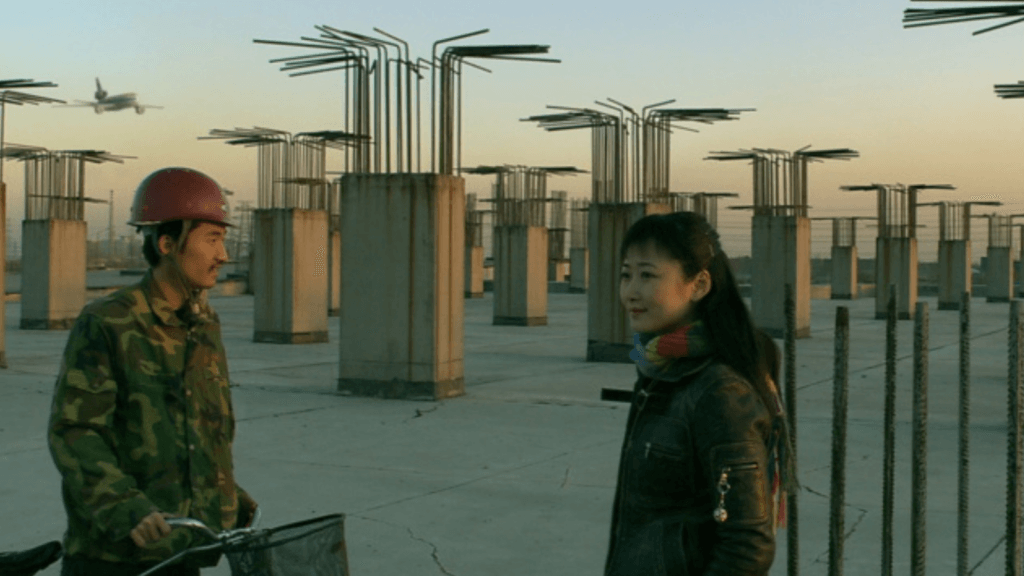

Jia said of his ambitions for The World, “I want to tell a true story in a false world that continuously sends back fake images.” His inspiration drew from Zhao Tao’s experiences working at Window of the World park in Shenzhen—an even larger version of the same concept as the World Park in Beijing, also featuring scaled-down versions of global landmarks. His film depicts visitors and employees as soon-to-be specters, alienated and passing through the park, creating surreal juxtapositions: Workers carry jugs of drinking water past a false desert in front of miniature Pyramids of Giza. Tourists capture forced perspective shots in front of the park’s smaller Leaning Tower of Pisa. Tao takes a slow-moving monorail to “India,” where dancers perform before a modest Taj Mahal, dancing to the song “Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy Aaja” (from the 1982 Hindi film Disco Dancer, later covered by M.I.A.). An employee brags over the park’s faux Manhattan island: “The Twin Towers were bombed on 9/11. We still have them.” In a part of the park that’s still under construction, unfinished support pillars with metal rods springing from the top look like a geometric concrete forest.

Structured around World Park’s various sections like a travelogue show, the film’s seemingly random details texturize Jia’s loose story threads and observational camerawork, giving The World an almost documentary aesthetic at times. This is particularly true when he captures the lives of workers. In one sequence, dancers look at the camera, smile, and genuflect as though the camera were part of the diegesis. While the visual oddity of the park always remains, the financially constrained lives of its workers interest the filmmaker more: After work, Tao and her friends unwind in a KTV (karaoke television) room illuminated by red light, escaping their troubles with heavy drinking. Taisheng’s cousin Erxiao (Ji Shuai) finds another way to manage; he works as a security guard but sneaks backstage to steal from performers’ pockets. Elsewhere, the park enlists a group of performers from Russia, and a shady facilitator takes their passports. Among them, Anna (Alla Shcherbakova) is understandably reluctant to hand over her passport, but she does anyway. She befriends Tao, though they cannot understand each other’s language. Tao tells her, “I envy you. You can go anywhere. What freedom!” But Anna proves just as trapped as Tao.

Each character emphasizes Jia’s point that China’s image of success conflicts with the lived human reality. The men toil in hard labor or resort to petty crime merely to scrape by. One character, nicknamed Little Sister, works overtime hauling steel until a cable breaks and injures him. He hoped to make a better living in Beijing but found himself overworked, underpaid, and ultimately dead after an accident resulting from his boss’ violation of safety codes. In his final act in the hospital, he writes down a list of his debts. Some of the women engage in sex work to gain some small measure of upward mobility, and most of them sell their looks one way or another. Tao believes her only chance at happiness lies in Taisheng, but she discovers he’s having an affair with Qun (Huang Yiqun), and that they may run away together. Everyone is trapped, both physically and psychologically. Their lives outside of work represent World Park’s backstage, and, like Disney World employees, their bosses require them to smile and appear happy.

Up until this point in his career, Jia had considered himself an “underground filmmaker.” However, he teamed with Shanghai Film Studio for The World, making his fourth feature his first officially sanctioned project released into Chinese theaters. Working with a much larger budget than usual, Jia and cinematographer Nelspm Lik-wai Yu employed elaborate camera movements on 35 mm. But most critics and viewers in China met the film with confusion over its contrasts between what is shown and the message the images convey. This represented a stark change in the type of cinema Chinese audiences were accustomed to; many mainland Chinese films prove unambiguous in their messages. The film fared better on the international festival circuit. But then, even for Jia, whose experimental flourishes, protracted takes, and enigmatic drama defined his earlier films, The World makes curious choices. The director injects animated sequences whenever someone checks their cellular phone—at a time before smartphones. The animation suggests the user has been transported into another mental realm by their device, a prescient look at the illusory freedom technology and personal devices supply.

The World has a cryptic ending, and even Jia admits he’s unsure what the scenes represent: a dream, a hallucination, or reality. While watching her friends’ apartment and avoiding her boyfriend, Tao receives a visit from Taisheng. It’s uncertain if he intends to run away with Qun or if he has returned to Tao. Either way, the two die from a gas leak, though it’s unclear if their deaths were accidental or from a murder-suicide. The screen fades to black. “Are we dead?” Taisheng asks. “No. This is just the beginning,” Tao says optimistically, their voices both emerging from darkness. Still, Jia’s film is far from optimistic about reality. He finds joy and pleasure in brief escapes, from after-work parties to animated sequences representing blissful connections. Ending in darkness and death, Jia’s lively metaphor turns the World Park into a hollow place where workers remain exploited and confined, leaving them with almost no identity outside their constraints.

(Note: This review was originally posted to DFR’s Patreon on February 25, 2025.)

Bibliography:

Frodon, Jean-Michel. The World of Jia Zhangke. Film Desk Books, 2021.

Mello, Cecília. The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2019.

Wang, Xiaoping. China in the Age of Global Capitalism: Jia Zhangke’s Filmic World. Routledge; 1st edition, 2019.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review