The Long Walk

By Brian Eggert |

(Editor’s Note: This review discusses major plot points in The Long Walk, including the ending. Best to read it after you see the movie if you care about spoilers.)

In The Long Walk, the so-called winners of a voluntary national lottery must keep walking until only one of them is left alive. If they move at a pace less than three miles an hour for more than three seconds, they get a warning. After a third warning, their armed military escort will shoot them. If they step off the road, they will be gunned down. Their only recourse is survival, to be the last one still walking. The winner receives untold amounts of money and a single wish granted, and maybe that’s what keeps them moving. Or perhaps it’s blind obedience to totalitarian rule. This televised spectacle is arranged by the fascist state to “reintegrate the value of work” and to counteract an “epidemic of laziness” in a dystopian postwar America. “We will be number one in the world again!” declares the Major (Mark Hamill), who oversees the twisted exhibition. Everyone else watches at home or from the roadside. The spectators on the shoulder look on with empty faces, frozen in a curious and helpless gaze, like someone who drives by a car accident and becomes transfixed by the ghastly sight—except here, the immobile onlookers watch a moving tragedy. As viewers, we watch and see a mirror held up to our country.

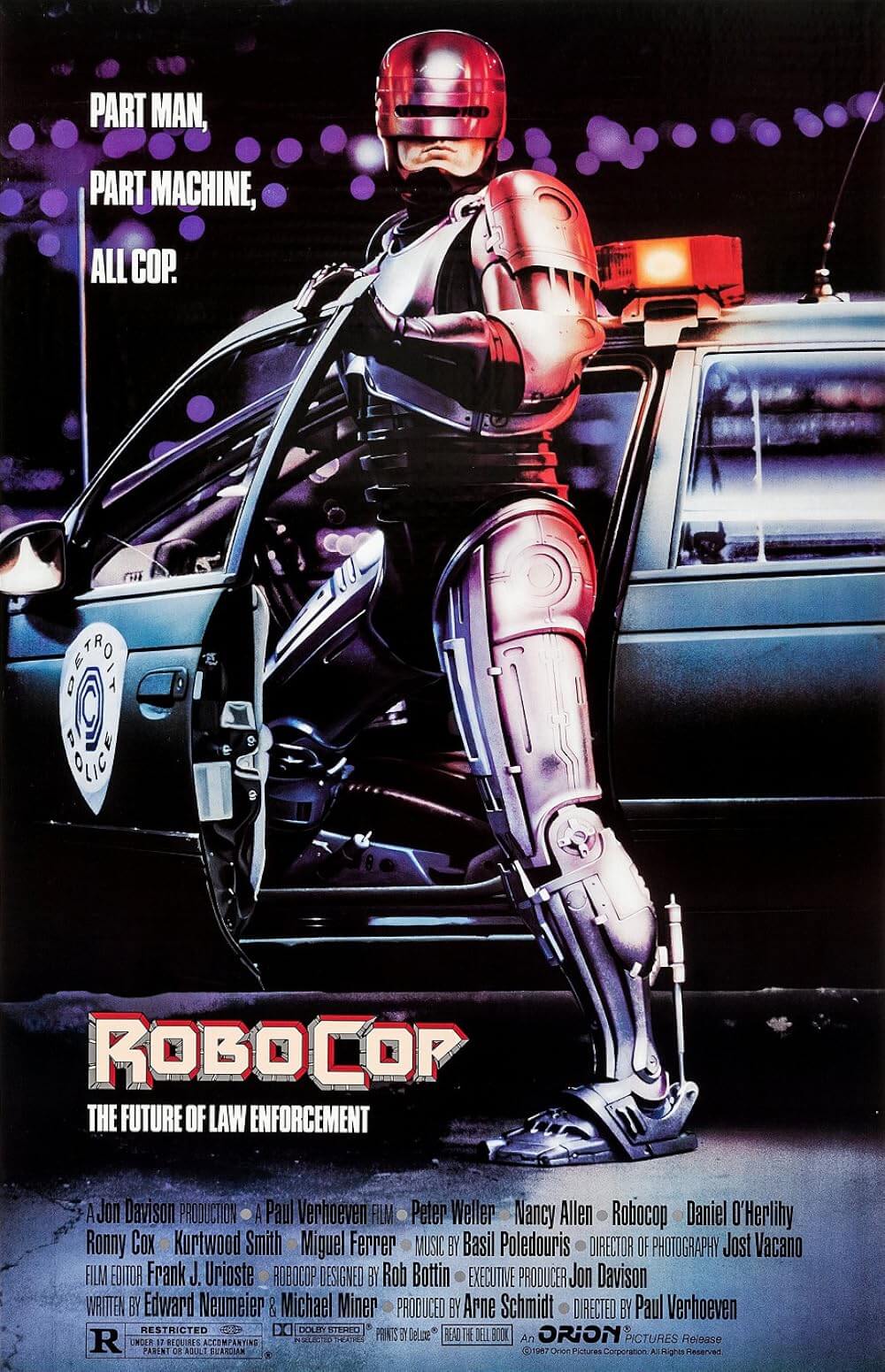

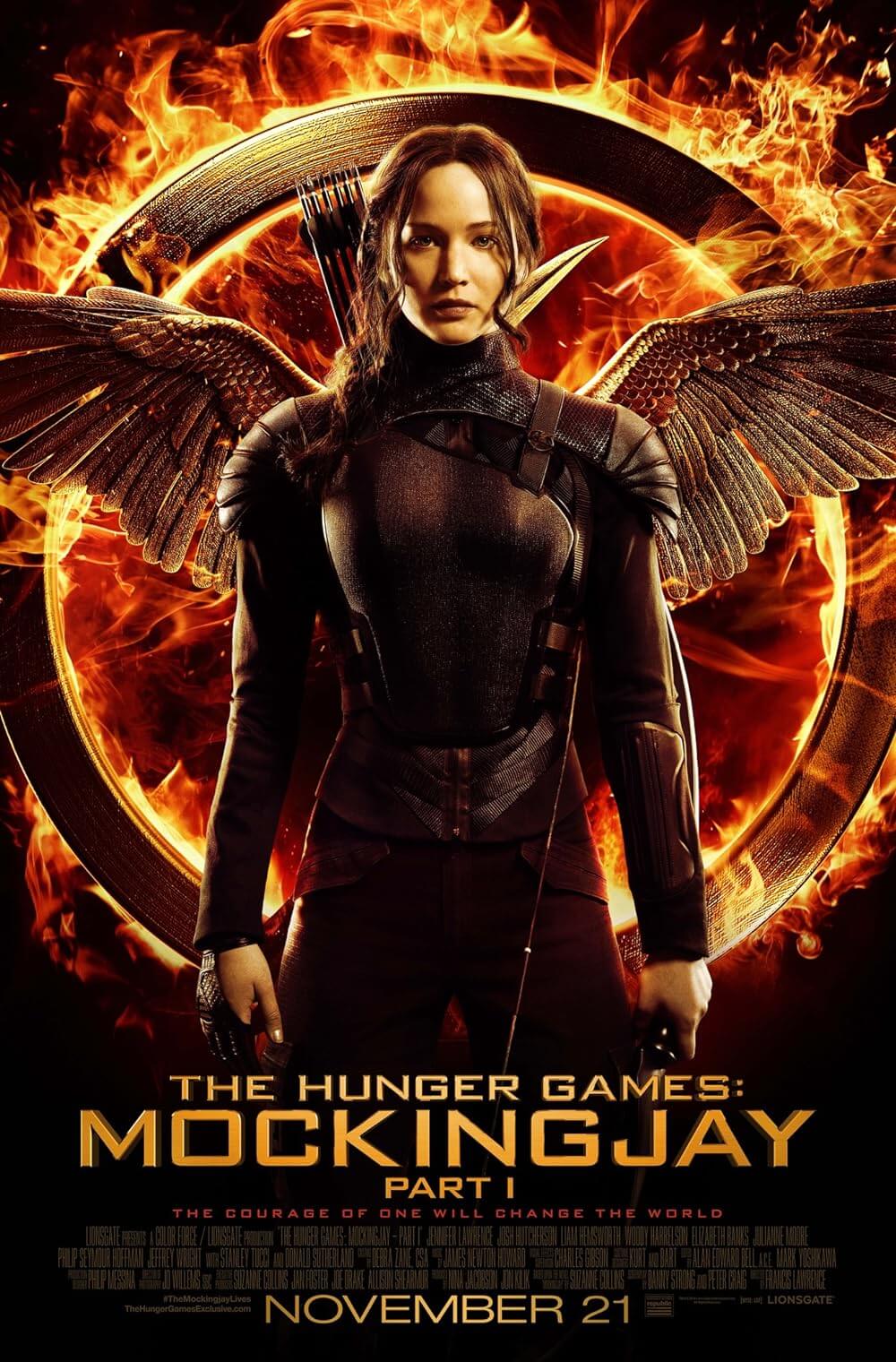

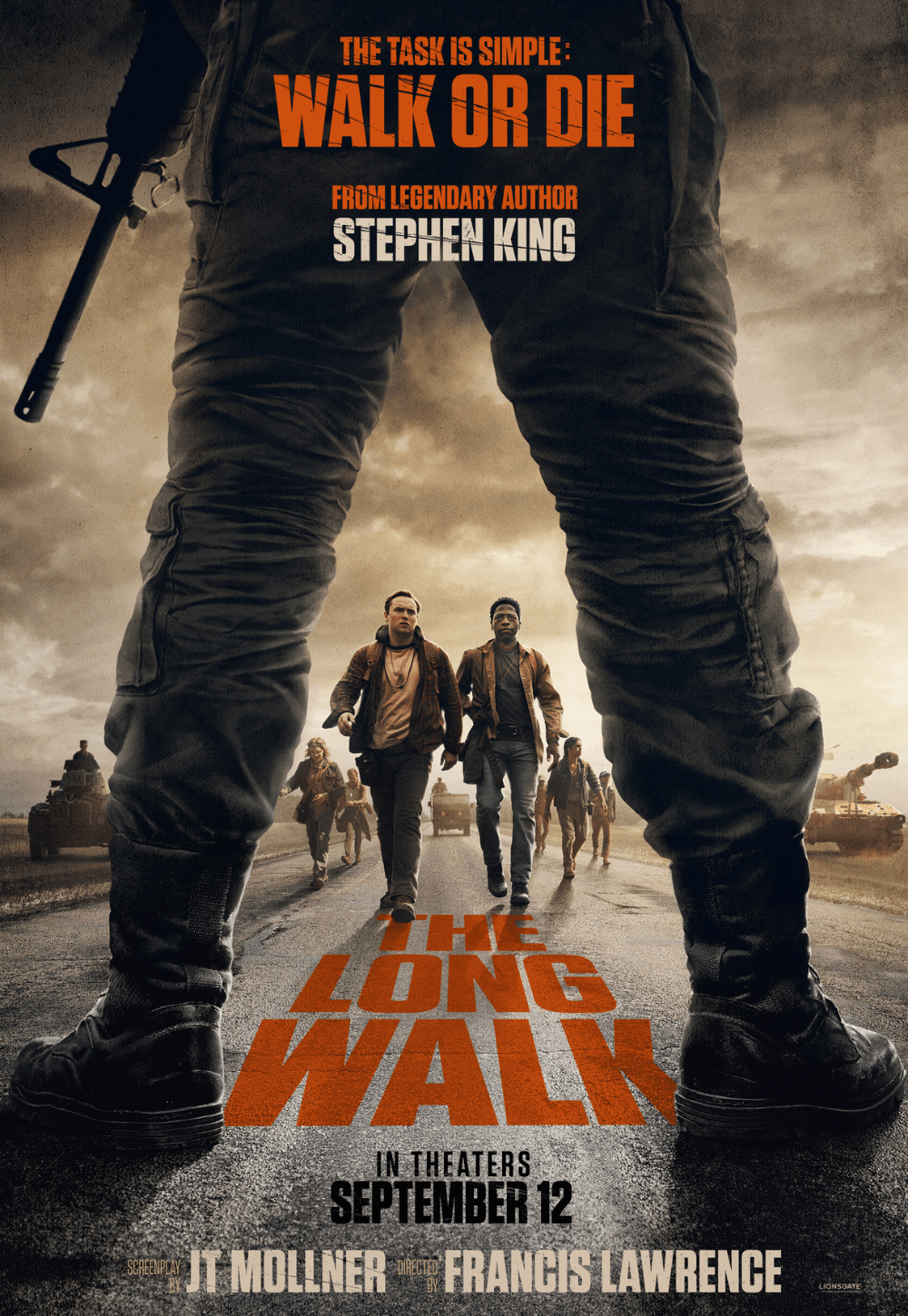

Based on the novel by Stephen King, published in 1979 under his harder-edged pseudonym Richard Bachman, The Long Walk was King’s first completed book in the late 1960s as a teenager. Given its unflinching brutality, it has had a winding path to the screen, with King-friendly filmmakers, including George A. Romero (The Dark Half, 1993) and Frank Darabont (The Mist, 2007), tapped to direct at various points over the last forty-plus years. In a curious yet apt turn, Francis Lawrence, who has been directing the Hunger Games movies since 2013’s Catching Fire, helms the adaptation, written by JT Mollner (Strange Darling, 2024). For Lawrence, it seems like another journey into a dystopian world where an authoritarian government exploits human capital as entertainment, using them as examples to control the masses, who consume the show in a begrudging complicity. Whereas the YA source material of the Hunger Games movies restricted the message to a PG-13 level of commercial accessibility, in The Long Walk, Lawrence takes off his gloves and delivers a raw-fisted blow to the audience’s gut, leaving us winded and gasping.

Lawrence establishes a time and place nondescript enough for an allegorical interpretation. The mise-en-scène resists specificity. Some of the automobiles appear to be from the 1970s, whereas the players of the Long Walk wear digital pedometers, suggesting a much later period, at least after the 1990s. The events follow a devastating war between unknown countries that left America in shambles and struggling to reconstruct. The vague setting reinforces its timelessness. Fittingly, the production design by Nicolas Lepage is stripped down, minimalist, with every color faded by sunlight and time. The filmmakers primarily shot on exterior locations in Manitoba, set against a backdrop of farms, empty fields, and the occasional small town. Jo Willems, Lawrence’s regular cinematographer since Catching Fire, never engages in ostentatious camera movements or angles. Much of the feature is composed of unfussy and simple shots, showcasing the relentlessness of the competition and hopelessness of its many players. Our only reprieve is a brief look into the past, shared as a dream, then a memory.

The participants consist of 50 young men—boys, really—aged around 18, one from each state. Our entry point is Ray Garraty (Cooper Hoffman), a genial, somewhat pudgy guy whose mother (Judy Greer) drops him off at the starting line. It’s through Greer’s desperate tears and pleading with Ray not to go through with it that we recognize the gravity of the situation. But Ray insists on participating. Although entering his name in the lottery for his state is voluntary, we learn that everyone puts their name in—not because it’s mandatory, but because it’s what’s expected of them by their country. Their government has coerced them into participation out of a combination of obedience and fear. That’s what oppressive governments do; they normalize their tyranny until everyone becomes a participant. Here’s a country where the state bans “ideas and materials” and breaks down the doors of offenders, giving them a choice: take an oath of allegiance or receive summary execution. Later in the film, Ray shares why he wants to win more than anyone else: His late father (Josh Hamilton) was confronted with that question, and he chose the latter.

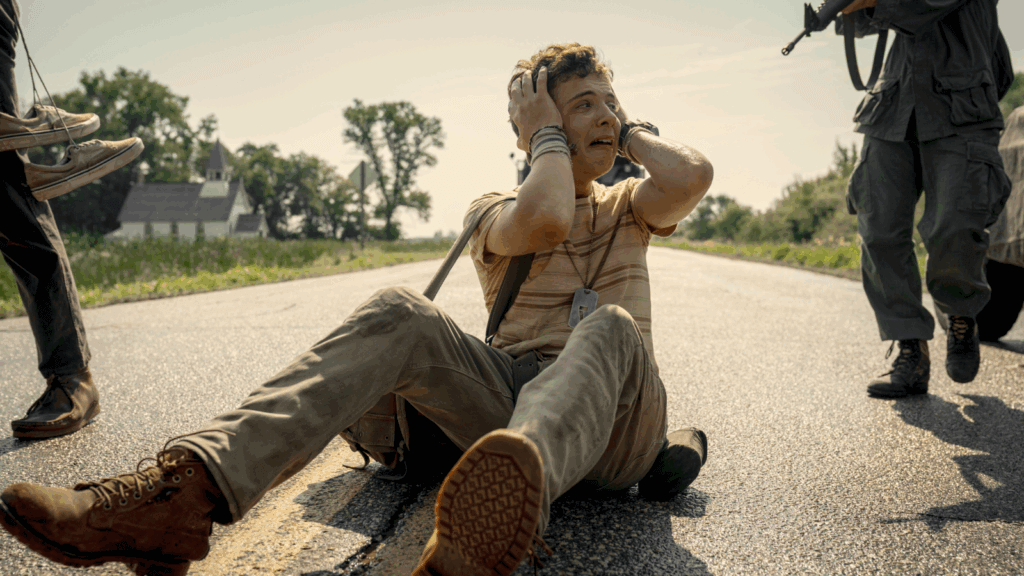

Each of the participants is identified and dehumanized even further by a numbered metal tag worn around their necks. Among his fellow walkers, Ray befriends Pete (David Jonsson), whose empathy and hopeful outlook engender a brotherly bond with several others: the friendly Arthur (Tut Nyuot); the unfiltered Olson (Ben Wang); and the writer Harkness (Jordan Gonzalez), who hopes to write a book about the experience, assuming he survives. Not all of them are so amiable. The unhinged Barkovitch (Charlie Plummer) taunts his competitors, hoping to upset their pace and thin out his rivals. The most physically capable of them is Stebbins (Garrett Wareing), a tall and muscular Adonis figure with a callous determination. The first of them to go might be the most tragic. Curley, played by Roman Griffin Davis—who also starred in Jojo Rabbit (2019) as a kid who survives Nazi Germany by losing himself in fantasies—lies about his age to compete in the Long Walk. Within the first few miles of a journey that lasts several hundred, a leg cramp slows Curley down and prompts his quick, unceremonious execution. The sweetest kid dies first, and badly. Lawrence isn’t messing around.

The violence and mounting physical toil in The Long Walk remain unsparing. Walking three miles an hour doesn’t seem that difficult at first, but try to keep that pace for 35 miles, 200 miles, or 300 miles without stopping. Lawrence doesn’t flinch when one of the walkers must relieve himself without slowing or another experiences diarrhea, nor does his camera look away from the frank gunshots, bloody feet, or other horrors. The Major watches over the procession from behind his aviator sunglasses, perched on his military truck, offering words of would-be encouragement that sound about as exaggerated and empty as Trumpian hyperbole. It gives the characters something to rally against. By mile 100, they declare, “Fuck the Major! Fuck the Long Walk!”—defying their government’s prohibition of negative statements about their insidious game. Despite the executions, suicides, sleepwalking, and tragic accidents, there are moments of great humanity, even sublime beauty, on display. One shot that stuck with me shows a blind cat on a line of mailboxes, its nose in the air, smelling the participants as they pass.

While some of the specifics—the number of participants, the rules, even the ending—differ from King’s book, The Long Walk captures the text’s unrelenting narrative thrust and message. Along with The Mist, the story remains one of my favorites by the author, effectively conveying the bleak commentary on state authoritarianism. Some have interpreted King’s story as a comment on the Vietnam War draft, where winning the disturbingly televised lottery meant a state-mandated death sentence for many Americans. In his subsequent books, King continued exploring fascist organizations and villains. A similar state-funded game show scenario unfolds in the King-Bachman book The Running Man. Elsewhere, King’s unforgettable characters, such as Mrs. Carmody, Kurt Barlow, Big Jim Rennie, Kurt Dussander, and others, embody the dogmatic need for control and obedience through manipulation and fear. Fittingly, King and Hamill have been vocal in their contempt of the current administration, which behaves in an ignorant yet aggressive manner, like many of the author’s most chilling characters. Given this, The Long Walk is both timeless and a vital reflector of today.

Fortunately, the film never treads into overt didacticism about its present-day parallels, even in its condemnation and open discussion of life under fascism. Central is the germane question of how to fight authoritarianism, explored in the differing worldviews of Pete and Ray. Pete thinks people should look on the bright side and notice the beauty in the world—the love shared in a family, the splendors of Nature, and so on. Ray hates living in an oppressed society and, should he win, wants to enact change by executing the Major. In the end, neither worldview prevails; it’s a combination of both. In the book, Ray’s eventual victory leaves his mind shattered, as he walks endlessly into madness. Lawrence and Mollner offer an angrier alternative in their film, as bleak as Darabont’s revised ending for The Mist. Ray sacrifices himself for Pete, who, in turn, carries out Ray’s plan to kill the Major. This conclusion suggests that Pete’s optimism and sunny outlook aren’t enough to overcome fascism. No one wins the Long Walk, and playing by their rules won’t bring about change. Instead, Pete recognizes that substantial hope springs out of meaningful action, devastating and fatalistic though that choice may be.

The Long Walk wouldn’t work without marvelous actors who convey the personalities and humanity embedded in their dialogue. Hoffman, whose father worked with Lawrence on the Hunger Games series, lends the picture its passion, along with an empathy for his fellow Walkers. Since his charismatic debut in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza (2021), Hoffman has amassed a string of impressive credits. As Ray, he conveys charm, humor, anger, and regret in a best-yet performance that carries the picture, particularly in his deteriorated, thinned-out appearance in the final stretch. He’s only matched by Jonsson, who broke out in Rye Lane (2023), and whose Pete is a rock until the final scenes. Each of the actors must imbue their roles with so much feeling and personality despite the constant movement required, yet they each find a way to make their walks and characters distinct. Greer is also excellent in her few scenes, showing us, through her anguished and heartbroken eyes, what the volunteers only realize well into the Long Walk—that their government has doomed them, one way or another, and their reward is a carefully constructed illusion.

Part cautionary tale, part dystopian nightmare, The Long Walk shares familiar ideas with King’s other book-to-film adaptations, from the shattering of youthful idealism in Stand by Me (1986) to the dangers of playing by an authoritarian’s game in The Running Man (1987, 2025). Today, it’s a reminder that every choice to remain silent or inactive against an oppressive system, or trying to beat an autocracy by playing by its rules, is not only futile but tantamount to complicity. Like King’s spare, grim text, the film is a stark form-follows-function piece of filmmaking that makes its point without the gloss or escapism of the Hunger Games series (a franchise that admirably tackles these concerns with broader appeal). The Long Walk is Francis Lawrence’s unfettered masterpiece and among the greatest of all Stephen King adaptations to the screen. And if it’s not the best film of 2025 so far, it’s perhaps my favorite for what the film has to say and the fearless way it tells its story.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review