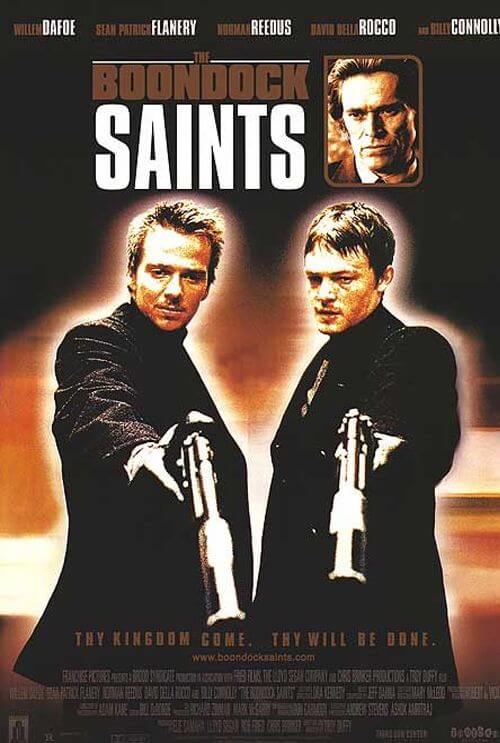

The Boondock Saints

By Brian Eggert |

Inexplicably admired by youth culture, The Boondock Saints follows dozens of generic, Quentin Tarantino-inspired crime movie rip-offs. This particularly mean-spirited flick from 1999, made by Boston bartender-turned-filmmaker Troy Duffy, reeks of artificiality. It plays out in a series of ultra-violent scenes edited together in a formless string, each one of them derivative. Popularized after strong direct-to-video sales, the movie eventually developed an obscure cult status. But Duffy, the movie’s inexperienced writer-director, proves the most interesting part of this bloody mishmash, his backstory offering a grim cautionary tale for rookie filmmakers.

As detailed in Overnight, the 2003 documentary assembled from footage shot by Duffy’s former friends Tony Montana and Mark Brian Smith, Duffy allegedly wrote his script after seeing a drug dealer lift money from a corpse in his apartment building. Disgusted by the seediness of his neighborhood, he envisioned two everyday Bostonians becoming vigilante heroes, and he wrote his yarn around that premise. After reading Duffy’s freshman script, Harvey Weinstein of Miramax outbid vying studios and took the project under his wing, calling it “Pulp Fiction with soul.” Weinstein budgeted the script at $15 million, and Duffy conveniently signed his own band, The Brood, to handle the soundtrack. Weinstein even bought Duffy’s hometown bar J. Sloan’s, for co-ownership with the up-and-coming director, to sweeten the deal.

What Weinstein originally saw in Duffy’s script is indiscernible. A premise Duffy’s own mother called “skewed,” the movie is about a couple of Irish good-ole-boys who, in wanting to relieve Boston streets of crime bosses and drug dealers, become killers. Backed by the local police and sanctioned by the Irish Catholic Church, Connor and Murphy MacManus (Sean Patrick Flanery and Norman Reedus) behave like over-stimulated hipsters who happen to kill bad guys. They walk about the streets of Boston in jeans, sunglasses, and pea coats, tattoos of the Madonna on their necks, smoking cigarettes because it’s cool. By day, they slap each other with raw meat in the bestest slaughterhouse ever, and by night, they rid the streets of human filth.

But they’re also extraordinary hypocrites, albeit unintentionally. Duffy glorifies his heroes as bona fide saints, hence the title. Just before killing a group of scumbags, they toke up with their accomplice, a loudmouth lunatic called Funny Man (David Della Rocco), whose gun accidentally discharges and kills a cat. Everyone has a good laugh about the accidentally mutilated feline, even its owners, a couple of strung-out junkies. And why do these “Saints” keep such questionable company and partake in illegal drugs? Because they’re not saints at all, just a couple of punks with guns, serving up their own impulsive sense of justice at the slightest whim. However much Duffy would like to usher these heroes into an underground sainthood, they’re quickly demystified through their contradictory, ridiculously annoying, and abrasive behavior.

The supporting cast luckily has a little more to offer. Willem Dafoe, who receives top billing, costars as FBI Special Agent Paul Smecker; he follows and admires these vigilante killers, and while dressing in drag, he mimics their handiwork. As he listens to opera and examines crime scenes, this homosexual Sherlock Holmes receives eye-rolls from local homophobic cops. An actor of incredible talent, Dafoe is too good for the material. Billy Connolly, meanwhile, makes an appearance as the Saints’ father, Il Duce, a notorious six-gunned hitman. Somehow, the character’s assassin abilities have been passed down to his children, with no formal training necessary. (Do hitman skills have some yet-undiscovered genetic basis, or did Duffy just pull that plot point from thin air like the rest of the script?)

Duffy’s entire production has a synthetic quality that’s trying much too hard to be trendy. Instead of meaningful vigilantism, the action scenes are about venerating bloodshed. The story is gruesome for the sake of being gruesome. Almost every line of dialogue contains the F-word; it’s used a reported 246 times within the movie—that’s more than twice every minute (halfway in, you begin to wish these saints practiced what they preached if only to cut down on the overused language). Duffy condemns peep show users, suggesting they should be gunned down, but then casts porno star Ron Jeremy in a pop-culture wink. His band’s soundtrack is comprised of techno and heavy metal, and it’s contrasted by an occasional gospel hymn over slow-motion. The entire production feels uneven, shoddy, and offensively oxymoronic.

It’s no wonder Miramax backed out before filming began, leaving the picture in limbo until Franchise Pictures picked up the reins. Duffy accepted Franchise’s deal for half the budget that Miramax offered; and when Miramax walked away, Duffy was required to return nearly a million in director and production fees back to the Weinsteins. But Duffy dug his own grave. Arguably the biggest, most influential force in Hollywood in the late 1990s, Harvey Weinstein had made an instant celebrity out of Duffy, a blue-collar Average Joe. Celebrities like Mark Wahlberg and Jeff Goldblum were talking about the potential greatness of Duffy; the media called him The Next Big Thing. But when the deal failed to materialize as soon as he would’ve liked, Duffy publically insulted Weinstein. He boasted “I’m Hollywood’s new hard-on,” and bragged about his success before his agreement solidified. He openly said Harvey Weinstein “wants to be me” and “he’s afraid of me.” Meanwhile, beer in his hand, in his overalls, Duffy continued to wait for Miramax to call.

At first, the local press covered his story as a rags-to-riches tale, and then it became a rags-to-rags warning about how up-and-coming filmmakers shouldn’t behave. Overnight shows Duffy shouting at his film’s experienced producer as though he’d been in The Biz for decades. He claims his family and coworkers don’t “deserve” money for their work, and that he has done everything. He later bullies those close to him when they confront his bad business decisions and tact. The lesson learned here is not that Hollywood corrupts, but that the possibility of Hollywood exposes: Overnight ends with a quote from author Albert Goldman saying, “No man is really changed by success. What happens is that success works on the man’s personality like a truth drug, bringing him out of the closet and revealing… what was always inside his head.”

After filming was completed, potential investors screened the finished product at the Cannes Film Festival somewhere in a sub-basement. All of Hollywood decided to pass, afraid to touch what Weinstein had made and then unmade. Eventually, in 2000, the movie earned a very limited release on five screens in the United States for a single week. The Boondock Saints make its second debut on home video. But Duffy had negotiated nothing in the way of video rights and ended up broke. Nevertheless, his movie’s popularity continued to grow thanks mostly to Blockbuster Video. Now, with the movie’s fame rising thanks to heavy rentals, an image search for the title on Google turns up mostly fratboys posing as the McManus brothers, and like Brian De Palma’s Scarface, they blindly idolize a movie because it’s violent and quotable.

If you comb through the reviews by other critics, it becomes apparent they remain baffled over the movie’s following. It’s a product that’s neither authentic nor entertaining, neither original nor innovative. Duffy himself comes close to overshadowing his sleepy yarn about glorified vigilantes, except the movie is so incredibly silly, so bafflingly overrated, that not even his undisciplined behavior among Hollywood’s elite can eclipse its insipidness. The Boondock Saints and Overnight suggest that Duffy is an angry, frustrated man who made an angry, frustrating movie. Incidentally, this critic is left feeling angry and frustrated thinking about the phenomenon—how it eludes understanding yet remains consistently lauded by fans.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review