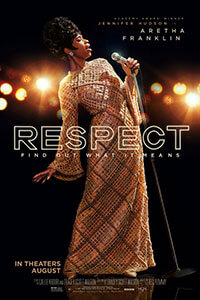

Respect

By Brian Eggert |

Dully committed to the musical biopic structure, Respect tells the story of Aretha Franklin, legendary musical artist and Queen of Soul. But you’ve seen this movie before, albeit under other names like The Doors (1991), Ray (2004), and Walk the Line (2005). They all follow the same narrative trajectory: a traumatizing childhood leaves scars on the subject artist, inspiring their passionate need to express themselves later in life; their modest early attempts at music reach a breakthrough when, usually during a studio recording session, the artist finds their unique sound; success leads to substance abuse and bad behavior, often sparked by memories of their childhood trauma; but after getting clean, they live out the remainder of their lives basking in their legacy. Even though Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (2007) spoofed these clichés to glorious effect, more often than not, filmmakers return to this template. It’s worth questioning whether these musicians’ lives are really so similar, or if Hollywood has just become so accustomed to framing them in the same way. Every so often, something like I’m Not There (2007) or Rocketman (2019) breaks the mold and rethinks the genre, but those examples remain few. Respect is a film that reveres its subject so much that it forgets to imbue Franklin with life.

After a few early scenes that kernalize Franklin’s youth (featuring the young Skye Dakota Turner), Jennifer Hudson takes over the role. Then, Respect approaches its subject with all the depth of a Wikipedia entry. Franklin’s overbearing father (Forest Whitaker) attempts to control how and when she performs, securing her a contract at Columbia that results in nine underwhelming records. Then she replaces one abusive man for another when she stands up to her father and marries Ted White (Marlon Wayans), prompting a switch of labels to Atlantic Records under producer Jerry Wexler (Marc Maron, excellent). She finds her sound in a few familiar recording studio sessions, including a seemingly improvised session of Otis Redding’s titular song. “It’s her song now,” declares Wexler—one of the film’s many lines of affirmation. Early in the film, she’s told, “Music will save your life.” Sure enough, when it happens, someone tells her, “Aretha, you did it.” A few notes about the Civil Rights movement here, a montage of Franklin’s success there, and 145 minutes later, the film has reduced Franklin’s life down to a Hollywood template.

Respect is actually the perfect title. Director Liesl Tommy and screenwriter Tracey Scott Wilson, who make their screen debuts here, resist turning the production into a showcase of the uglier episodes from Franklin’s life. However, she experienced sexual abuse, battery, and psychological manipulation, and those moments receive only brief attention, usually off-screen and referred to as her “demons.” Consider her bout with alcoholism, which the filmmakers address in three efficient scenes: First, a scene shows Franklin drinking too much and yelling at her family and entourage; then, intoxicated, she falls off the stage in Columbus, GA; finally, she wakes up in a stupor one morning and commits herself to a gospel reform. It’s efficient storytelling, I suppose, but it’s a calculated breakdown of the artist’s experience that reduces her life to checked-off narrative boxes. As a result, these moments never feel alive, whereas other biopics seem urgent with trauma and cycles of abusive behavior. Take the superb Tina Turner film, What’s Love Got to Do with It (1993), which adheres to every predictable scene in the musician biopic structure. And yet, the actors (Angela Bassett, Lawrence Fishburne) commit to making their characters electric with intense domestic and stage scenes.

Hudson never disappears into Aretha Franklin. The costumes by Clint Ramos recreate Franklin’s iconic look during specific stage performances, and the hair and makeup team do their best to make Hudson look the part. But there’s a spirit missing to the performance, even though Franklin reportedly selected Hudson for the role and insisted it would earn her another Oscar (after 2006’s Dreamgirls). Of course, the former American Idol winner sings Franklin’s songs using her own voice, and that’s part of the problem; she never disappears into the role, not visually or aurally. Franklin’s distinct vocal personality makes her songs what they are, filled with soul and pain and defiance. Hudson doesn’t quite capture that spirit, though objectively, her voice is incredible and showy—it’s just not Aretha. For a better vocal performance and perhaps a fuller portrait of Aretha Franklin, watch Cynthia Erivo in the third season of the National Geographic television miniseries, Genius: Aretha. Or better yet, watch Aretha herself at the end of Respect, singing “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” at the 2015 Kennedy Center Honors tribute to Carole King. It’s moving stuff, and it’s more engaging than the entire film.

Watching Respect, the viewer can sense the production’s overriding desire for Oscars. Hudson, last seen under CGI fur in 2019’s abysmal Cats, executive produced this project, and there’s a hint of vanity and look-at-me showiness to the part. There’s no doubt that Hudson can put herself into the role, but the film lacks the dynamism or perspective that would make the material come alive. The biggest misstep is concluding the film with Aretha’s recording of her album Amazing Grace, partly because the recording, which took place at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles in 1972, was released as a documentary feature in 2018. The doc shows Franklin in her prime, pouring everything into a redemptive and powerful live performance meant to declare her recommitment to gospel music, not to mention God. And while the filmmakers attempt to recreate the experience through attention to surface details, there’s a profound lack of energy in these scenes. Like most others in Respect, this sequence seals up the open-hearted quality of Franklin’s music and performances, leaving the entire thing to feel safe and humbled instead of vital and personal.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review