Predator: Badlands

By Brian Eggert |

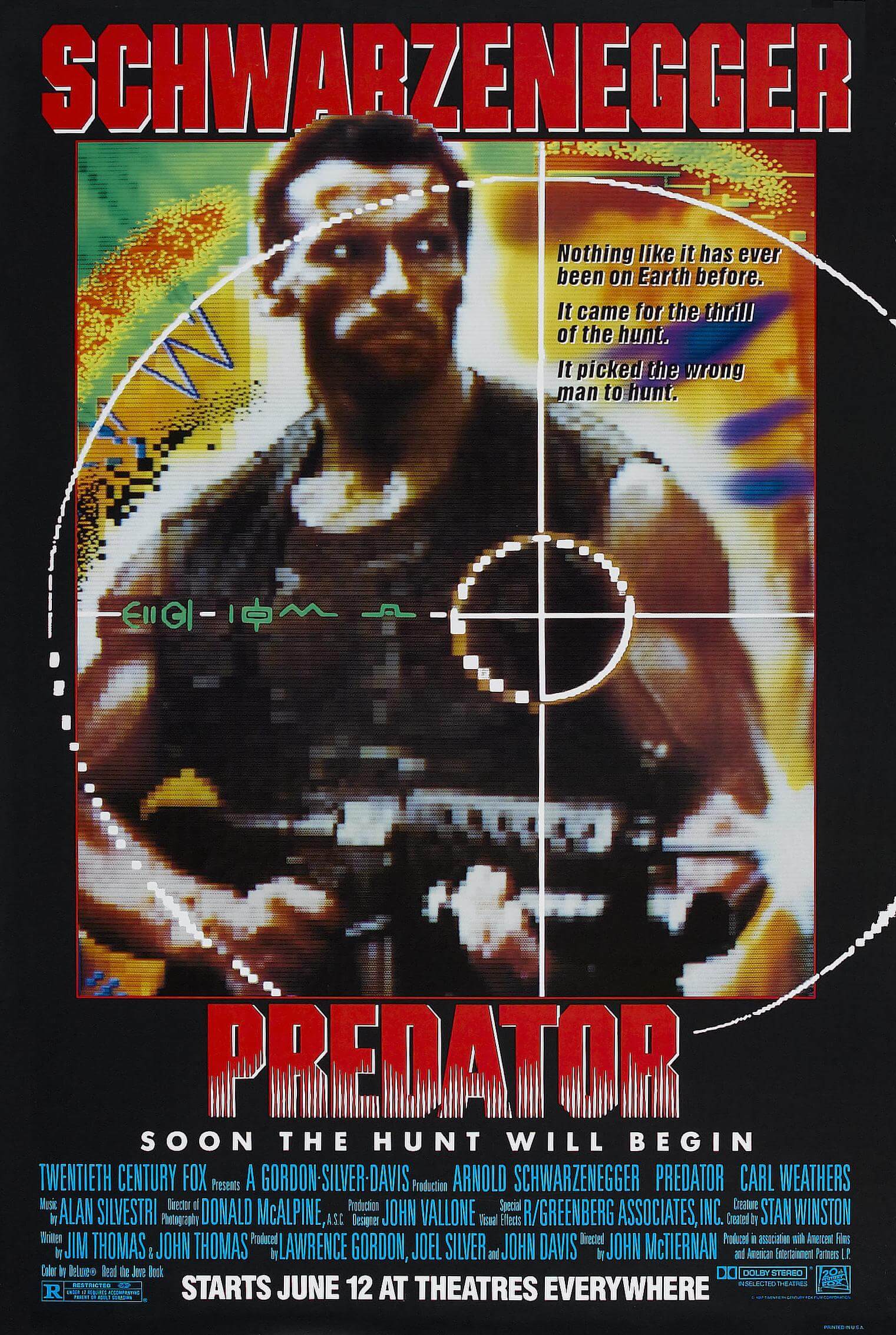

Almost 40 years ago, the Predator franchise began as a 20th Century Fox vehicle for Arnold Schwarzenegger, featuring R-rated shoot-‘em-up violence and an alien hunter—realized with incredible practical makeup effects by Stan Winston—who collected its victims’ skulls as trophies. Today, the latest installment of the franchise, now owned by Disney, is engineered for moviegoers accustomed to PG-13 blockbusters and features a big-eyed monkey-dog rendered in subpar CGI (sure to be a plush toy on shelves this holiday season). Predator: Badlands marks the seventh entry in this frustratingly uneven series (ninth, if you include the two abysmal Alien vs. Predator titles from 2004 and 2007, which, after this one, we may have to). There have been worse Predator movies and a couple of better ones than Badlands. What makes the latest so maddening is that it comes oh-so-close to delivering a fully satisfying entry, an increasing rarity for the movies about these mandible-mouthed, tendril-haired killers. However, for all of its pleasures—and there are plenty—it can’t sustain them until the end.

Returning to the director’s chair is Dan Trachtenberg, who brought new life to the franchise with 2022’s Prey, which the Disney-owned 20th Century Studios unceremoniously dumped on Hulu. Prey thrived in its spartan plot, centered on Naru (Amber Midthunder), a young Comanche warrior who squares off against a Predator on the Great Plains in 1719. That movie ended with a cliffhanger, pitting Naru against more Predators. Instead of following that thread, Trachtenberg co-directed this year’s animated anthology Predator: Killer of Killers while completing Badlands, which exchanges Naru for a new story set on a far away planet in the distant future, focused entirely on a Predator. There’s not a human in sight. It also loosely ties the Predator franchise to elements from the Alien franchise, no doubt setting up a future encounter. Given the abortive outcomes the last two times these movie monsters met onscreen, it’s hard not to feel cynical about another IP crossover. At least Trachtenberg finally resolved to give the Predator species a name beyond a nonspecific noun. Once they reach adulthood, prove they can hunt, and earn their invisibility cloak, Predators call themselves Yautja.

The first few minutes of Badlands open on shaky ground. Mirroring a sequence that opens Meg 2: The Trench (2023), we see a series of ever-larger bugs and lizards preying on each other until the arrival of Dek (Dimitrius Schuster-Koloamatangi), a broken-toothed, adolescent Predator who aspires to become a Yautja hunter. Trachtenberg practically auditions to direct the next Star Wars feature here: Dek appears hooded, like a Jedi, and carries a lightsaber-esque plasma sword that slices through flesh and metal with ease. To join his clan as a full Yautja, Dek must prove his hunting skills by acquiring a legendary prey. However, Dek’s honor-obsessed alpha father condemns his runtishness and would rather cull the weakness from his clan than give his youngest son a chance. In a move that plays like Shakespearean drama written in the original Klingon, the father kills Dek’s sympathetic older brother for defending his younger sibling and sends Dek away to Gemma, the dangerous home planet of the Kalisk—a beast that, if acquired, would prove Dek’s worthiness.

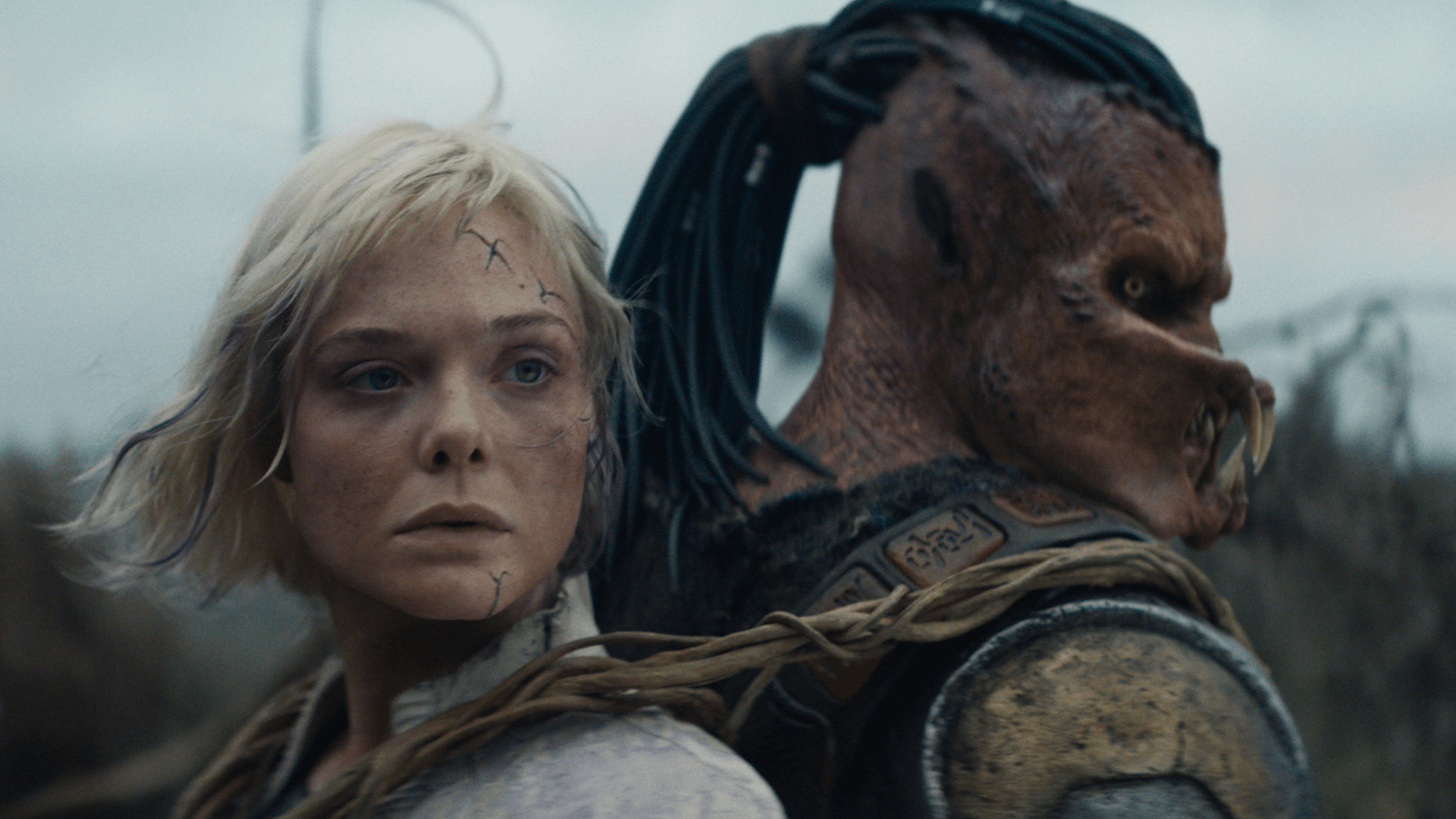

The best scenes in Badlands occur early on and involve Dek stranded on Gemma, acclimating to its deadly flora and fauna. For a while, the movie unfolds wordlessly in elegant visual storytelling, recalling the first third of Riddick (2013), where our hero must survive a treacherous alien environment. Dek encounters Chekov’s exploding caterpillar, weeds that shoot poisonous proximity darts, razor-sharp grass, and acid-spitting slugs—all of which will later replace his tech-arsenal: the lightsaber, an electric bow, throwing razors, and various other gizmos. Before long, he encounters the plucky Thia (Elle Fanning), an android from the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, the evil company from the Alien franchise bent on developing bioweapons. Legless, Thia has been halved by the dreaded Kalisk. She convinces Dek to tether her to his back to help him navigate the planet. With her presence, one gets the sneaking suspicion that Thia might represent an argument for AI usage—Dek calls her a “tool,” a word often used to defend AI, and this artificially intelligent android becomes not only useful to Dek but the most affable character in the movie.

Even though Yautja believe in honor and self-reliance above all—empathy, friendship, and forgiveness are weaknesses—you can be sure Dek and Thia become friends on their perilous journey. She speaks in English; he speaks in subtitled Yautja. Somehow, they understand each other. They have a pleasant chemistry reminiscent of the begrudgingly bound pairings in It Happened One Night (1934) and The 39 Steps (1935), with her chatty and sensitive presence softening his tough exterior, molded by the stubborn, self-obsessed values of Yautja glory and sport hunting. Thia soon leads him to the location where the Kalisk last attacked, where she last saw her android twin, Tessa (also Fanning), with whom she yearns to reunite. Of course, apart from Bishop in Aliens (1986), Weyland-Yutani androids don’t have the best track record for trustworthiness. Besides fighting the Kalisk, a creature that can quickly regenerate after any wound, Dek also must take on a small army of android goons.

The minimalism of Prey gives way to maximalist Hollywood excess in Badlands, with Trachtenberg relying on excessive CGI of inconsistent quality. Dek is rendered digitally with motion-capture technology and mostly looks convincing (until the film’s final shot). But results vary with other animals on Gemma, as well as the action sequences. For the most part, Trachtenberg maintains visual cohesion. An early fight between Dek and some carnivorous vines proves intense, and the finale offers a clever sequence where Thia’s two halves fight together. Unfortunately, the movie loses coherence once it descends into a messy, unintelligible battle between Dek, a silly ultra-huge Power Loader from Aliens, and the Kalisk. Most atrocious is Bud, the aforementioned monkey-dog creature, who becomes the cute puppy in Dek and Thia’s makeshift clan. Introducing an adorable friend into the mix is pedestrian enough, but the choice is made worse by its subpar CGI, bringing to mind the terrible-looking Blarp from Lost in Space (1998).

Fortunately, Trachtenberg and his screenwriters (Patrick Aison, Brian Duffield) build goodwill with Dek and Thia’s charming rapport. Schuster-Koloamatangi and Fanning play their roles well, with welcome notes of humorous banter and even slapstick. Their presence also gives way to themes about overcoming limitations and questioning culturally enforced values. Both Dek and Thia have physical shortcomings: he’s small compared to other Yautja; she’s bisected. Dek has been raised to believe in the Yautja’s loner ideology, which holds that might is right and empathy is a weakness, and the clan must weed out anyone with perceived deficiencies. Thia has been programmed by Weyland-Yutani with certain mission priorities. Regardless, they overcome their physical disadvantages and conditioning, and they find strength in friendship and teamwork, with Thia teaching Dek about how they both can choose the life they want. Dek learns that he doesn’t share Yautja values, at least not those of his father, while Thia demonstrates she can ignore her programming. And by extension, Badlands reads as a rebuff of eugenics and what Elon Musk monstrously deems civilization’s “suicidal empathy.”

After the stripped-down simplicity of Prey, Trachtenberg overdoes it with Predator: Badlands, resorting to an overblown, uneven implementation of CGI that occasionally leads to digital blindness—a phenomenon that overloads the eyes, rendering everything onscreen a jumbled, indecipherable mess (think every Transformers movie). Perhaps some Disney executive demanded a stuffed spectacle to justify its higher budget (Prey cost $65 million; Badlands cost over $100 million) and theatrical distribution, even though Prey would have looked stunning if released in theaters. And while it’s worth seeing Badlands on the big screen for the effective first two-thirds, its disappointing finale—crammed with repetitive dialogue, helping hands, and touching foreheads—dumbs down the proceedings in a desperate attempt to manufacture a crowd-pleaser (no doubt to minimize the financial risk and justify its higher budget). Sure enough, the audience cheered and even applauded during the preview screening, perhaps because Badlands operates in the customary Hollywood tentpole mode that we’ve all grown accustomed to seeing. But that’s the problem, especially after the inspired innovations of Prey.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review