Peter Hujar’s Day

By Brian Eggert |

Peter Hujar’s Day is an entire feature that breaks the movie rule to show, not tell. In 1974, author Linda Rosenkrantz made an audio recording of a conversation with her close friend, the photographer Peter Hujar, renowned for his monochrome images of Fran Lebowitz, William S. Burroughs, and many others. She hoped to include the transcript in a book about the daily lives of artists, detailing what they did between waking up in the morning and going to sleep at night. She never completed the project, and her interview with Hujar, recorded on December 19 of that year, was believed lost. A tape of the conversation was rediscovered in 2019 in Hujar’s archives at the Morgan Library & Museum, and it was published as a 36-page text in 2021. That text provides the basis for Ira Sachs’ new 76-minute feature showcasing Hujar’s account of his previous day’s events. The result examines an artist’s life, complete with Hujar’s shrewd introspection, wry observations, and commentary on New York and its culture in the 1970s.

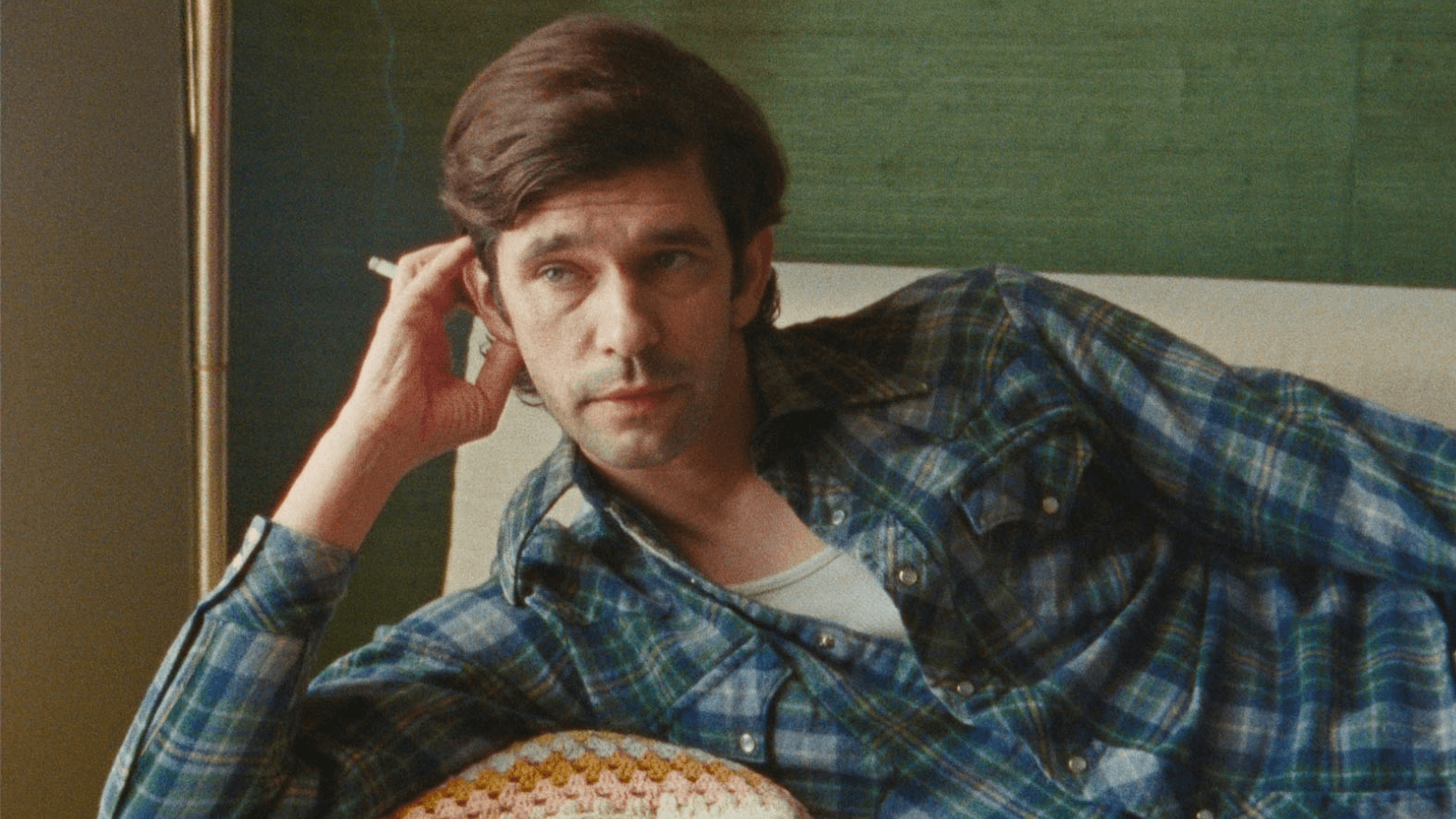

The closest comparison might be Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre (1981), another filmed conversation between two New Yorkers; however, even that seems more conventionally cinematic than Peter Hujar’s Day. Sachs eschews poetic licenses that would ease the viewer into the material and explore his characters’ inner lives beyond the original recording, such as the narration in Malle’s film or, say, dramatizing the events before and after the interview. He merely looks on as Hujar and Rosenkrantz, played by Ben Whishaw and Rebecca Hall in extraordinarily subtle and lived-in performances, talk in Rosenkrantz’s Upper East Side apartment. The film is a two-hander, with no extras or extraneous information whatsoever. And yet, it has an entrancing effect despite its simplicity, probably because of it.

Hujar’s name-droppy account begins with a call from Susan Sontag, a visit from an editor at Elle, and a trip to Allen Ginsberg’s place to photograph him for The New York Times. He takes various calls from fellow artists and shares Chinese takeout with photography critic Vince Aletti. He ends the day developing photos in his darkroom. Throughout their talk, Hujar remarks on the process of recalling his day in such detail once he starts, but the conversation isn’t a one-sided recitation of events. He also has an intimate friendship with Rosenkrantz, and their familiarity, from their personal history to their shared circle of friends, emerges in Rosenkrantz’s limited but telling interruptions. Their talking extends over an afternoon until the sun sets in the evening; they eat cheese and dessert, munch on pistachios, and drink spirits. Hujar moves about the apartment, from her couch to the table, from her bed to the balcony. At one point, the conversation stops so they can dance to Tennessee Jim’s “Hold Me Tight” on a 45.

Sachs captures the conversation on 16mm film stock in a desaturated ‘70s color palette, accented by production designer Stephen Phelps’ immersive retro details. Alex Ashe’s cinematography adopts a grainy, almost fuzzy appearance and avoids close-ups for the most part, preferring to show the warm body language between these two close friends in medium and master shots. Hujar and Rosenkrantz rest their hands and heads on one another, their intimacy and trust unmistakable. They also convey a harmony of the sort only artists can experience with other creatives, allowing for a shorthand in their conversation. It’s a curiously engrossing look at the artist, who died in 1987, ten months after an AIDS diagnosis. But it’s not without visual beauty, despite the interior setting. Sachs and Ashe put forth stunning images of the subjects silhouetted against the setting sun or city skyline.

Whishaw—who gave another excellent performance in Sachs’ last feature, the love triangle Passages (2024), on the set of which the two bonded over their affinity for Hujar—does most of the talking, of course, and he’s hypnotic in the role. However, with far fewer lines, Hall has the more difficult task of being an attentive listener. Watching Hujar recount his day, my eyes often drifted to Hall, whose nuanced work is revealed in active stillness. Rosenkrantz never finished her planned day-in-the-life book about several artists, but she mentions that she hopes to publish, to learn how more productive people spend their days; she feels like she does nothing all day long. Watching this film, I mourned that incomplete project and recognized the distant yearning in her eyes, listening to someone whose output was more disciplined. Those eyes sometimes drift into the camera’s lens and hold our gaze for a moment, often in compositions that evoke Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), as if to remind us, “He may be speaking, but I am the author of this project.”

At the same time, Sachs includes glimpses of his production’s clapboard and boom mic, along with brief flashes of untrimmed celluloid in the edit, to expose the aesthetic façade of Peter Hujar’s Day. In this, Sachs reveals his own artistic pretenses while his film considers what goes into being an artist, evaluating your work, getting paid, and finding motivation. His deployment of musical interludes and grand choral music to contrast the conversational banalities—such as the benefits of owning a couch for sex, relaxation, or whatever—render the experience oddly profound. Through Hujar’s words and Sachs’ film, the practicalities and mindset of artists form into both a distinct individual portrait and a sweeping, yet microcosmic look at what it’s like to be an artist in this place and time.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review