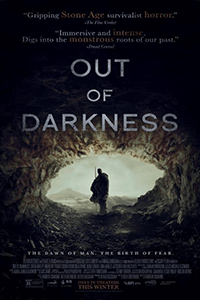

Out of Darkness

By Brian Eggert |

Out of Darkness opens with a shot of a vast landscape at night, the land utterly black and the sky a deep blue. A small orange fire breaks the oppressive darkness, calling attention to itself for miles. Here, some 45,000 years ago, a group of early humans tells stories around their campfire. They establish legends about themselves as great travelers who set out from their old world to explore the unknown, led by their resident hero, and find a “promised land” rich with animals, a clean water source, and healthy soil to grow crops. Their ambitions involve no more than having a place to raise children and keep their elders safe. A film about prehistoric humans clashing with the unknown, Out of Darkness marks a confident debut from director Andrew Cumming, whose treatment is straightforward yet mostly unflinching in its narrative thrust.

Initially titled The Origin, the movie premiered at the BFI London Film Festival in 2022, where many compared the result to Dan Trachtenberg’s Prey (2022)—the prequel to Predator (1987) set on the Great Plains in the eighteenth century, involving a Comanche tribe confronting a deadly alien. However, Cumming’s scenario, written by Ruth Greenberg, isn’t about humans clashing with an alien creature, regardless of how much it occasionally feels akin to Outlander (2008) or other genre-inflected movies of that ilk. Instead, Out of Darkness belongs in the camp of sweeping prehistoric survival stories such as Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Quest for Fire (1981), Michael Chapman’s The Clan of the Cave Bear (1986), Felix Randau’s Iceman (2017), and Albert Hughes’ Alpha (2018).

The story follows a modest group of six explorers determined to find a new home. Their social hierarchy follows a Paleolithic order, where the alpha male, Adem (Chuku Modu), leads the others: the elder Odal (Arno Luening); Adem’s pregnant mate Ave (Iola Evans); his son Heron (Luna Mwezi); a younger warrior Geirr (Kit Young); and a young “stray” girl, Beyah (Safia Oakley-Green), who has just reached maturity and thus serves a “purpose” to Adem. While searching their new land, Adem and Geirr find evidence of something monstrous. The group can hear screeching in the night, and the sight of a mass grave teeming with bloody bones suggests a bad omen. What could be out there? A forest demon? A monster? A swamp thing? Some animal they have never encountered before? When whatever it is takes Heron one night, the group must search the dark forest nearby to find him.

Shot in Scotland, the production looks appropriately wild and prehistoric. Cinematographer Ben Fordesman captures the landscape in stunning vistas and overhead shots that dwarf the characters within their surroundings. The camerawork becomes shaky and unintelligible in more intense scenes, hoping to create tension. But the gory result of attacks and, later, cannibalism, offer more by way of potency. So, too, does the superb score by Adam Janota Bzowski, whose music recalls Mica Levi’s unearthly sounds in Under the Skin (2013).

Shot in Scotland, the production looks appropriately wild and prehistoric. Cinematographer Ben Fordesman captures the landscape in stunning vistas and overhead shots that dwarf the characters within their surroundings. The camerawork becomes shaky and unintelligible in more intense scenes, hoping to create tension. But the gory result of attacks and, later, cannibalism, offer more by way of potency. So, too, does the superb score by Adam Janota Bzowski, whose music recalls Mica Levi’s unearthly sounds in Under the Skin (2013).

The production looks sharp and plays well, though the austerity of the narrative left me wanting more, even though its forward momentum is immersive. At 87 minutes, Cumming and Greenberg’s setup resolves itself just as it seems to provide some answers. Where the comparisons to Prey prove apt is the movie’s treatment of Beyah, a young woman who, not unlike Amber Midthunder’s character in that prequel, is disregarded because of her gender. In the second half, Beyah takes charge of hunting down the thing that’s hunting them, becoming the resident Final Girl and an undervalued warrior by the third act.

But then there’s a curious reveal in the finale that, if you want to remain unspoiled, you should skip to the next paragraph. Just as Beyah has been undervalued, the creature hunting them has been presumed evil. “They weren’t monsters. They were just like us,” one character affirms. In the end, it’s all just a terrible misunderstanding between the humans and the resident Neanderthals, who have every chance of working together to make a community despite their differences. To be sure, the scientific community has argued that homo-sapiens likely wiped out the Neanderthals, though genetic evidence exists of some inter-species breeding going on behind cave walls. The movie’s message is that people shouldn’t be so quick to judge. Still, there’s no adequate explanation as to why—beyond fear and the self-preservation instinct—if the Neanderthals are so misunderstood, Heron was initially taken, nor why several characters meet such gruesome ends at their hands.

In its late developments, Out of Darkness uses its conflict to comment on universal issues of prejudice and discrimination. While similar in structure to Prey and the aforementioned prehistoric adventures, it also remarks on Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, wherein new knowledge reshapes our worldview. But the mainly visual filmmaking has more appeal than its themes, accented by the production’s minimal use of its made-up language via subtitles, which sometimes sounds vaguely familiar. Cumming demonstrates that he has a clear and compelling vision, delivered in shocking scares, immersive suspense, and convincing performances from the cast. The missteps in the final moralizing scenes may threaten to derail the entire movie, but it’s a gripping experience nonetheless.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review